Subtotal: $

Checkout

An Antidote to Christian Celebrity

Small-town saints challenge us to rethink our approach to success.

By Andy Stanton-Henry

April 24, 2023

Available languages: español

Successful Saints

In the beautiful film A Hidden Life, about the Austrian farmer Franz Jägerstätter who refused to sign the soldier’s oath of loyalty to Hitler, there is a scene in which Jägerstätter is confronted by a fellow prisoner. Throughout the film, a host of people tell him to swear the oath and do whatever he has to for his and his family’s survival. God will understand. And his prison-mate is no exception. He launches into a speech born out of hopeless weariness: “Have the meek inherited the earth? How far we are from having our daily bread! How far from being delivered from evil! If we could only see the beginning of his kingdom … but nothing. Ever.” After “twenty centuries of failure,” Christianity needs to try something different. “We need a successful saint,” he concludes.

Though I’ve certainly not experienced the level of tribulation visited upon Jägerstätter and his prison companion, I can empathize with that sentiment. Sometimes I wish we could elect the right president, select the right movement leader, hire the right pastor, and watch this “successful saint” set things right.

On the other hand, in my lifetime I’ve seen a number of “successful saints” who disappointed people by not meeting their messianic expectations or, worse, centralized power and abused followers, all the while being supported by people insisting that these leaders were “God’s man” or “God’s woman” and we should not “touch the Lord’s anointed.”

There’s another word for “successful saints”: celebrities. There has been a lot of conversation lately about the dangers of celebrity Christianity, and I don’t want to try to close the wound before it has been fully examined. But I have been thinking about the remedy, or perhaps a preventative medicine. In the spirit of the Jesuit principle agere contra (“to act against/contrary”), I’ve been pondering the practice of hiddenness as a kind of counter-virtue to celebrity.

To be sure, there is much in our Christian tradition that calls us to speak up, stand up, share good news, spread our message, and so on. There’s the Great Commission, of course, but also teachings from Jesus like the one in Matthew 5:17: “Let your light shine before others, that they may see your good deeds and glorify your Father in heaven.” In this testimony of our tradition, being seen and heard are important parts of Christian practice and important means of spreading God’s kingdom. While it may be a prominent testimony, it’s not the only one. There are “minority reports” that are worthy of consideration, ones that just might “speak to our condition,” as my fellow Quakers say.

Rethinking Saints

The testimony of “hidden holiness” may be the minority report we need. I became acquainted with that term from Orthodox priest and writer Michael Plekon. In his book Hidden Holiness, he spotlights a variety of saints and offers the witness of their lives as ordinary people who simply sought to be faithful to God in their time and place. He invites us to lay aside the “cult of celebrity saints” and see these figures as testimonies to the “the universality, diversity, and ordinary qualities of sanctity in our time.”

Hidden Holiness introduced me to the Yupik Orthodox woman named Matushka Olga Michael, who lived faithfully in rural Alaska as a midwife, mother, neighbor, priest’s wife, and advocate for the sexually abused. Olga was no celebrity, but she remains a saint in our memory and a human being worthy of emulation.

I also recently learned about Phocas the Gardener, a man who loved God and neighbor in Turkey, near the Black Sea, growing food on his land and using it to care for the poor and persecuted. As the story goes, he even hosted and fed the soldiers sent to kill him before they reluctantly carried out their order.

These types of saints were not known for performing mighty miracles and being “movers and shakers” in the world. But they carried out their calling in “hidden holiness,” and lives and regions were impacted as a result. We are still talking about them generations later.

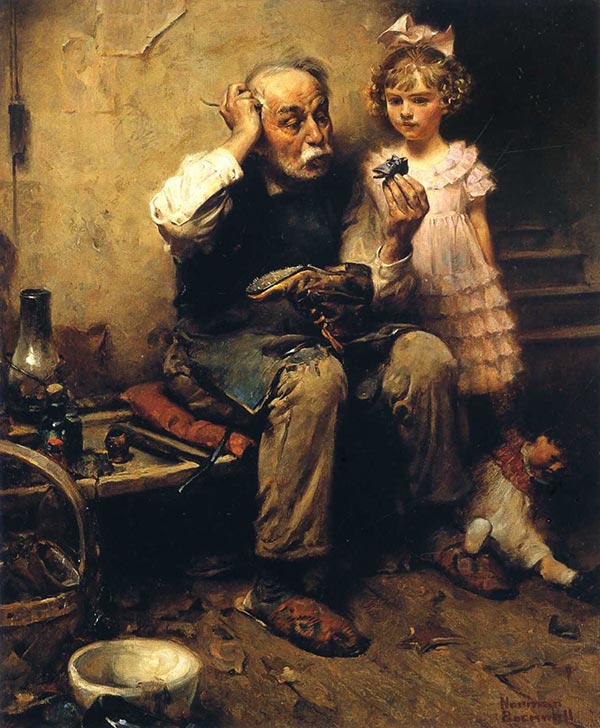

Norman Rockwell, Cobbler Studying Doll’s Shoe, 1921

In her book Celebrities for Jesus, journalist Katelyn Beaty points out that fame may be spiritually risky but isn’t inherently wrong. Fame can be natural and helpful if it arises from “a life well lived, not a brand well cultivated.” She continues: “At its best, fame is a by-product of virtue, the effect rather than the goal of a virtuous life. When we live as people who love well, serve sacrificially, pursue truth and justice, put others ahead of ourselves, and make the most of our time on earth, sometimes other people notice.” This fame need not develop into “celebrity,” which Beaty defines as “social power without proximity.” Celebrities influence through the illusion of intimacy whereas ordinary saints influence through relationship and embodied witness.

Beaty’s work on fame and celebrity reminds me of the “small-town famous” concept. Many rural communities have locally famous residents whom people admire for their skills as a mayor or seamstress or baseball player or mechanic. We respect them for their skills and service but, because we live in real proximity to them, we know their humanity well.

We all have a “communion of saints” we honor and emulate, whether we call it that or not. Besides historical figures considered saints by the wider church, there are folks in my own family history that I remember with gratitude and reverence. My paternal grandparents, for example: they weren’t perfect people, but they were kind and faithful and humble. They farmed a piece of land, served a local church, loved and prayed for their families, and endured hardship with grace. I want to be like that. We need fewer celebrities and more saints like Olga and Phocas and Grandpa and Grandma Henry.

Rethinking Success

In order to counter celebrity Christianity’s grip, we also need to reframe our definition of success. Many Christian celebrities say that Christians don’t have to be “successful” as defined by our culture, but their priorities and pocketbooks say something very different. And there is some nuance here. People of faith are called to be “fruitful,” to steward our time and energy with intentionality to love our neighbors and serve God’s kingdom. But the “God’s kingdom” part changes everything that comes before. It’s no longer only about “relevance” or “effectiveness” or “productivity.”

I’m helped by Ralph Waldo Emerson’s lovely poem “Success.” It redefines success with a list of alternative definitions like laughing often, winning the respect of critics and the affection of children, and leaving behind a legacy in the form of a healthy child, a garden patch, or improved social condition. Emerson concludes: “To know even one life has breathed easier because you have lived – this is to have succeeded.” That’s the kind of sainthood and success I want. Ultimately, “success” is a standard negotiated by each of us, as we consider our place, our relationships, our calling, and our corner of God’s kingdom.

Wendell Berry draws from a surprising source to define success: the Amish farmer. In his poem “Amish Economy,” Berry paints a picture of the good life, centered on an Amish father, sitting under a tree with his daughter on his lap, contented after a full day of good work on his land:

This is because he rose at dawn,

Cared for his own, helped his neighbors,

Worked much, spent little, kept his peace.

Thomas Merton had some rather strong views on success. He wrote, “If I had a message to my contemporaries, it is surely this: Be anything you like, be madmen, drunks, and bastards of every shape and form, but at all costs avoid one thing: success.” What is the great danger in Merton’s mind? “If you are too obsessed with success, you will forget to live. If you have learned only how to be a success, your life has probably been wasted.” Our obsession with success – whether economically or in our leadership – keeps us from actually being saints, which Merton defined as becoming our true selves in God. It keeps us from actually living and it keeps us from actually leading.

Elsewhere, writing to a peace activist, Merton speaks similarly against our focus on traditional standards of effectiveness:

Do not depend on the hope of results.… You may have to face the fact that your work will be apparently worthless and even achieve no result at all, if not perhaps results opposite to what you expect. As you get used to this idea you start more and more to concentrate not on the results but on the value, the rightness, the truth of the work itself.… Gradually you struggle less and less for an idea and more and more for specific people.… In the end, it is the reality of personal relationships that saves everything.

I think Merton is describing the development of a mature redefinition of success. We take on a new set of metrics. All of them have to do with relationships – nurturing, deepening, and honoring them. But relationships are best worked out privately. We may admire loyal friendships and loving families, but we aren’t likely to make a good dad or lifelong buddy into a celebrity. Relationships remind us that so much of holiness is hidden.

Rethinking Scripture

There is a fair amount of talk about hidden holiness in the Bible. But before we consider what the Bible does say, it’s worth paying attention to what it doesn’t say. By that I mean the “hidden years” of Jesus. We don’t know a lot about them, but they make up the majority of Jesus’ life. Naturally, we emphasize Jesus’ years of public ministry, but surely the many preceding years were not wasted. They were years of learning, developing, and preparing, to be sure, but they were also part of Christ’s redemptive and revealing work for humankind. In her book Liturgy of the Ordinary, Tish Harrison Warren connects these years to the meaning of the incarnation:

Christ’s ordinary years are part of our redemption story. Because of the incarnation and those long, unrecorded years of Jesus’ life, our small, normal lives matter. If Christ was a carpenter, all of us who are in Christ find that our work is sanctified and made holy. If Christ spent time in obscurity, then there is infinite worth found in obscurity.

Some of us will have public years of ministry; others of us will live our entire lives in “long, unrecorded years.” But the Incarnation reminds us that those are not wasted years outside of God’s redemptive work in and through us.

The hidden years of Jesus also provide a path for us to follow for faithful life and leadership. Henri Nouwen wrote:

When we think about Jesus we mostly think about his words and miracles, his passion, death, and resurrection, but we should never forget that before all of that Jesus lived a simple, hidden life in a small town, far away from all the great people, great cities, and great events. Jesus’ hidden life is very important for our own spiritual journeys. If we want to follow Jesus by words and deeds in the service of his Kingdom, we must first of all strive to follow Jesus in his simple, unspectacular, and very ordinary hidden life.

And yet, Jesus of Nazareth was a famous person. The gospels report that it didn’t take long for his fame, or pheme in Greek, to spread quickly across the countryside (Matt. 4:24; Mark 1:28). How did Jesus handle this fame? It’s possible that he leveraged it, to extend his reach widely, so as many people as possible could experience the healing grace and kingdom message he offered. But it wasn’t something he chased.

In Mark’s Gospel, especially, we get this practice of the “messianic secret.” We read of him “ordering” people “not to tell anyone” (Matt. 16:20; Mark 7:36). Why the secrecy? Maybe it was strategic: he wanted to prolong his ministry as long as possible before a confrontation with the authorities. Or maybe he was concerned that the message would be corrupted or convoluted when spread through rumors about a new, famous prophet. In other words, it was Jesus’ way of saying “keep it secret, keep it safe” (to borrow from Gandalf), protecting his message from the dangers of celebrity.

We know that Jesus was “pro-secret” from other passages, too. In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus warns his followers about doing their “works of righteousness” (almsgiving, praying, fasting) in order to be seen by others. Instead, he recommended practicing their faith “in secret” – kruptos: hidden, secret, concealed.” He reminds them that God sees this secret and sacred work, for God is also “in secret” (Matt. 6:4–6).

In his provocative book Secret Faith in the Public Square, Jonathan Malesic argues that several figures from Christian history have embraced this “secret” tradition and we inherit their wisdom. Cyril of Jerusalem protected the gospel’s integrity in fourth-century Christianity by practicing the “discipline of the secret” in which the knowledge of the sacraments was withheld until a catechumen was baptized. Kierkegaard advocated a “secret faith” in his nineteenth-century Danish context, encouraging anonymous acts of charity and neighbor-love in resistance to the emerging consumer capitalism that relied on bourgeois commercial exchanges. And Bonhoeffer, in his context of rising Nazi domination, preserved authentic faith by supporting secret meetings for prayer, worship, and the sacraments “behind closed doors” in a way that countered the rise of religiously-enabled imperialistic nationalism.

Malesic argues that these historic examples preserved Jesus’ teaching on secret faith. And he argues that reclaiming this tradition is “the only way [American Christians] can prevent the continued degradation of their religious identity.” I wouldn’t go as far as Malesic, but I think he’s on to something. Practicing our hidden holiness enables us to maintain authentic faith and avoid the traps of celebrity culture. It also enables us to resist those powers seeking to co-opt our faith for their own purposes.

In the larger biblical narrative, we can learn from stories in the Hebrew Bible such as Ruth and Esther. Their stories pay scant attention to miracles; they rarely mention God, actually. But they follow these women and their friends and family as they seek to be faithful in their time and place. Faithfulness in the midst of shifting circumstances sometimes moves them into positions of influence but it’s not because they are seeking power or fame. Ruth and Esther remind us of the power in living fully and faithfully in hidden holiness. They also remind us that God is often working beautifully and redemptively behind the scenes, in hidden ways. Maybe it’s time to recover a spirituality of Ruth and Esther in our day. Maybe we do well to follow Paul’s advice to the folks in Thessalonica: “Make it your ambition to lead a quiet life: You should mind your own business and work with your hands” (1 Thess. 4:11). We’ve seen the fruit of “celebrity for Jesus”; maybe it’s time to quietly, faithfully live our hidden holiness and let God use us in whatever secret, creative, redemptive ways God sees fit.

Rethinking Social Justice

This call to a life of hidden holiness may be troublesome to folks committed to active lives of social justice. This is a legitimate concern. It may be important to make a distinction between holiness as a life of hiding from and hiding for. It’s possible to remove ourselves from positions or opportunities for public ministry because we are hiding from the responsibility and vulnerability that they bring. This is fear, not faithfulness. But it’s also possible to remove ourselves from public view as a way of hiding for the integrity of our faith and actions.

We do well to remember the witness of folks like Dorothy Day and Clarence Jordan – not to mention countless monks, nuns, farmers, country preachers, doctors, etc. – who intentionally rooted themselves in a community where they could do gospel work in effectual but unglamorous ways. Their practice of social justice was not abstract but embodied in their profound commitment to stability of place and depth of relationship. In some ways, the more they immersed themselves in the hidden holiness of local work, the more effective their public testimony became. Private, local faithfulness is not the opposite of social justice; it is a legitimate expression of social justice. And it gives integrity and energy to our activism.

We often face a fear articulated well by Scott Russell Sanders. Sanders writes: “For all my convictions, I still have to wrestle with my fear – in myself, in my children, and in some of my neighbors – that our place is too remote from the action.” How does Sanders deal with it? “I deal with my unease by asking just what action I am remote from – a stock market? a debating chamber? a drive-in mortuary? The action that matters, the work of nature and community, goes on everywhere.”

Indeed, the action that matters goes on everywhere. In all kinds of places and in all kinds of roles. In the kingdom of God, we don’t dismiss the farmer’s seed or the widow’s mite or a child’s few loaves and fishes. God collects all our small but significant contributions and makes miracles with them. We do our part, we do our work with faithful presence, and we entrust the rest to God’s creativity, with no thought “for the morrow” or the logic of celebrity.

In The Inner Voice of Love, we get an inside look into Henri Nouwen’s wrestling with his calling as he feels the tension between hidden holiness and his growing popularity. Perhaps his words also speak to our own wrestling:

You still think, even against your own best intuitions, that you need to do things and be seen in order to follow your vocation. But you are now discovering that God’s voice is saying, “Stay home, and trust that your life will be fruitful even when hidden.”

Perhaps the present Christ is saying something similar to today’s leaders. “Stay home” – practice your hidden holiness, love locally, serve quietly – and “trust that your life will be fruitful even when hidden.”

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Trisha

We are so drawn to recognition, our egos demand a constant diet of human praise, and money is the earned tribute for our hard work. That is me. I crave those rewards. I crave human achievement. But my heart is drawn to and I remember all the faithful servants of God in my life- all my life- all pointing to a different joy, where faithfulness itself is a reward of grace, and I strive, yet again, to reset my internal compass.

Andrew Burke

Thank you, Andy for this very thoughtful essay. I recently came across a prayer called "The Litany of Humility" by Cardinal Merry de Val (1865-1930). It is prayerful echo of your fine words and people may like to look it up. Thank you also for mentioning the haunting movie -A Hidden Life. It is perhaps worth highlighting the words from Middelmarch from where the title is taken. “The growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.” – George Eliot, Middlemarch

FW

A rich reflection…thank you. I am nearing the end of my ‘public’ ministry and as I survey the past years, I am struck by, and thankful for, the wholesomeness of littleness, quietness, faithfulness in place. I wonder too if there is a theology of anonymity which might speak to the serious stumbling blocks for ministers which result from fame and celebrity?

Denis Lahaie

I can only add that I admire the sainthood of Canadian born Brother André Besette. I have his biography on my bedside table, written by one of his contemporary. It is a wonderful tale of spirituality, struggle with dark forces and unfortunately struggle with the religious establishment (envy, incomprehension, late recognition).

Denis Lahaie

I can only add that I admire the sainthood of Canadian born Brother André Besette. I have his biography on my bedside table, written by one of his contemporary. It is a wonderful tale of spirituality, struggle with dark forces and unfortunately struggle with the religious establishment (envy, incomprehension, late recognition).

Jackson

This is an illuminating essay. Thank you for all the food for thought. It is so easy to get swept up with presentation and appearance these days as social media looms large. It is tempting to post everything on there these days. As I prepare for my public ministry, I will keep this essay in mind.

Bruce Hollenbach

This is a most precious essay. Very counter-cultural and pro-christian. I live in an "assisted living" community and so find the "hidden" part of hidden holiness to be a piece of cake. The only remaining challenge is the "holiness" part :). I appreciate the reproduction of the Norman Rockwell painting of the cobbler helping the little girl with the problem of her doll's shoe. It fits the essay perfectly. Here is a man who not only helps a child but who also enters into her problem with her, allowing her to participate in the process of solving it with him, giving her dignity and recognition. This girl will never forget this, and she will become a better woman for it. I think Rockwell has been devalued, as a feature of American kitsch, whereas he was a front line defense of the values that are being lost. I'm getting a print of this painting to put up on the wall where I live. Thank you.