Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Oberammergau’s Broken Vow

-

The Unutterable Silence of God

-

The Mind in Pain

-

In Search of Solace

-

Where Are the Churches in Canada’s Euthanasia Experiment?

-

Letters from a Vanishing Friend

-

The Dust on All the Faces

-

Two Thousand Years of Christian Strangeness

-

God’s Purpose in Your Pain

-

Saving Friends: What I’ve Learned from Insufferable Patients

-

The Speaking Tree

-

The Way of the Passion

-

Chinese Christians’ Costly Allegiance

-

Baptism Means Leaving Home to Find It

-

Felix Manz: The Making of a Young Radical

-

The Return of the Bison

-

The Communion of Empty Hands

-

Poem: “Zeal”

-

Poem: “Winter”

-

Editors’ Picks: Demon Copperhead

-

Editors’ Picks: How to Inhabit Time

-

Editors’ Picks: Faith, Hope and Carnage

-

The Gift of Palliative Care

-

Transforming Food

-

On Planting Sugar Maples

-

Letters from Readers

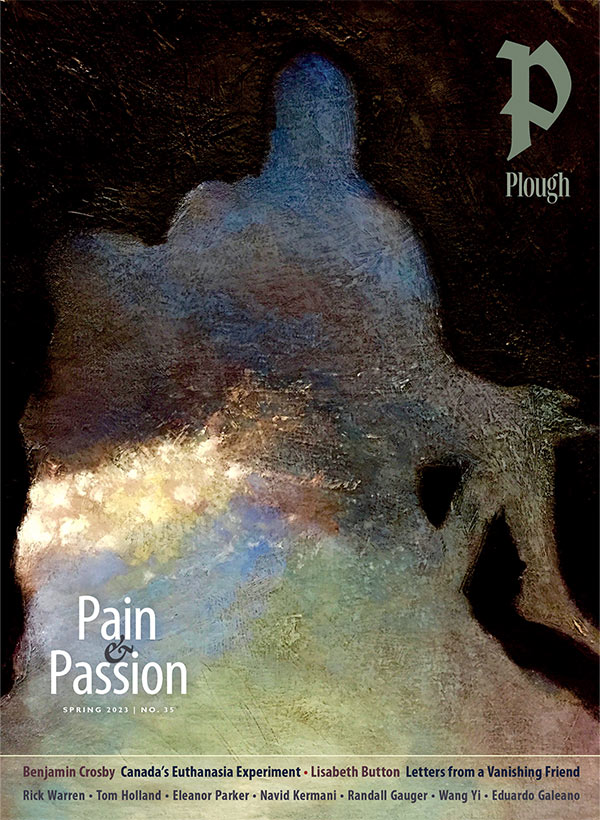

Covering the Cover: Pain and Passion

An eloquent sculpture evokes the themes in this issue: the redemptive nature of suffering, and the hope implicit in the Easter story.

By Rosalind Stevenson

February 25, 2023

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

The conversation surrounding this issue’s cover centered on the questions that pain raises. Why do people suffer? And can any good come of it? As this is our Spring issue, coming out at the beginning of the Lenten season leading up to Easter, it seemed clear that the artwork should be derivative or allegorical of the Passion of Christ. After floating various concepts – including Caspar David Friedrich’s landscapes with crosses, saints and martyrs, stigmata, and Easter imagery such as thorns, spear, or cross – we found ourselves returning again and again to the powerful image of Michelangelo Buonarroti’s Madonna della Pietà. This eloquent marble sculpture brings together the themes of physical pain (Christ’s crucifixion and death), compassion or “suffering with” (Mary holding her son), the redemptive nature of suffering, and the hope implied in the story of Easter.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Madonna della Pietà, 1498–1499

Two representations of this image stood out: one, a detail of the statue showing Mary’s face as she looks on her son, reflecting his pain. This appears on the back cover, along with an excerpt from the “Stabat Mater,” a Christian hymn from the thirteenth century that speaks of Mary’s suffering as she beholds Jesus crucified and asks that we might share in the suffering of them both, and so share in the victory of the cross:

Eia, Mother, fount of love,

Make me feel the power of sorrow

that I might mourn with you.

For the front cover, we chose Daniel Bonnell’s 2018 painting Pieta Meditation #1. This semi-abstract oil painting depicts a silhouette of Michelangelo’s statue, surrounded by darkness with light breaking through. The sorrow of Mary with the broken body of her son is still there, giving shape to the form – but through it, a glimpse of the hope that lies beyond.

Another View

Edvard Munch was born in 1863 in a farmhouse in Løten, Norway. When he was five, his mother died of tuberculosis, and he lost his sister nine years later to the same disease. The family was poor, and his father suffered from mental illness, as did some of his siblings. Confined to his bed by sickness for much of his childhood, Edvard would occupy himself by drawing. By his teenage years, art had become his primary focus. He enrolled in a technical college for engineering, but dropped out due to poor health and his wish to pursue art. His childhood influenced his approach to art; as he wrote in his diary: “In my art I attempt to explain life and its meaning to myself.”

Edvard Munch, Spring Plowing, oil on canvas, 1916

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.