Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Readers Respond Summer 2016

-

Serving Children in Pyongyang

-

Blessing out of Pain

-

Life Together: Beyond Sunday Religion and Social Activism

-

Solidarity

-

Possessions

-

Differences

-

Let Yourself Be Eaten

-

Repentance

-

At Table

-

Poem: Rainfall

-

From Property to Community

-

Why Community Is Dangerous

-

Confessing to One Another

-

The Way: Two Millennia of Christian Community

-

Friars of Manhattan

-

American Hospitality: Jubilee Partners

-

Live Like You Give a Damn

-

The Luxury of Being Surprised

-

The Incident in Changu’s Pepper Patch

-

Two Poems

-

Editors’ Picks Issue 9

-

The Jesus Indians of Ohio

-

Three Open Wounds

-

Why I Love to Wear a Head Covering

-

Vincent van Gogh

-

All Things in Common?

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

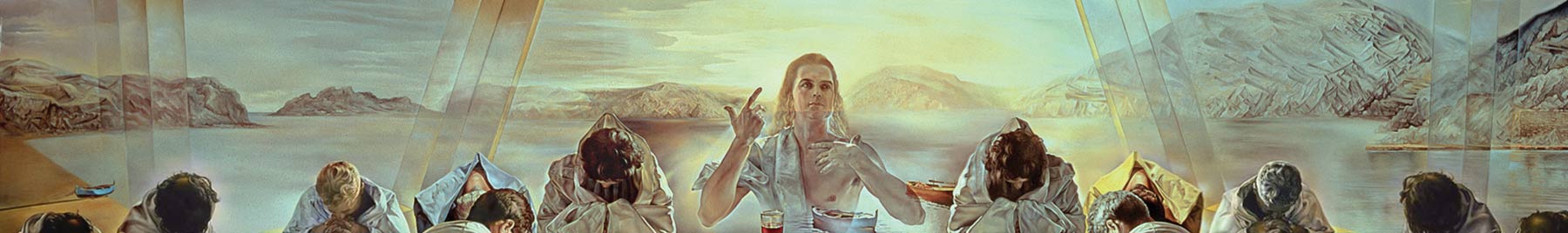

Salvador Dalí (1904–1989) took most of the year 1955 to complete this painting, which he then donated to Washington’s National Gallery of Art the following Easter. Not long before, Dalí had re-embraced the Catholic faith of his upbringing after discovering the writings of Saint John of the Cross. As a result, in his artistic work he had turned to what he called “nuclear mysticism,” exploring the intersection of science, mathematics, and faith. Even in the atomic age, Dalí maintained, “not a single philosophic, moral, aesthetic, or biological discovery allows the denial of God.”

While both Christian and secular viewers have found The Sacrament of the Last Supper jarring, even shocking, that is precisely the point. As Max Kramer said in a February 2010 sermon at St. John’s College, Cambridge:

Here we seem to have a bold artistic statement of the notion that we find in the creation story that man is made in the image of God – so even God the Father can be depicted in the image of man. ... The apparent stillness of the painting is balanced by Jesus’ gesture of movement. As we are drawn closer into the painting, we are drawn [to] the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit ... to the place prepared for us at the table ... not a place where we can stand or sit – both of those gestures would spoil the whole symmetry of the work and block the sight of Jesus. It is a place where the only correct posture is to kneel.

For it is by kneeling in prayer that we can share in the fellowship of Christ’s praying disciples, it is by kneeling in prayer that the light of Christ will fall upon us, it is by kneeling in prayer that the gifts of the eucharistic bread and wine that we see set on the table are offered to us – gifts which, so the centripetal force of the painting’s symmetry suggests, will draw us ever closer to Christ and through him into the love of the Trinity.

Painting by Salvador Dalí (1904–89) / National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, USA / Bridgeman Images / © Salvador Dalí, Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Reproduction, including downloading of Salvador Dali works is prohibited by copyright laws and international conventions without the express written permission of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Mike Talbert

Dali always manages to surprise, even in familiar works. This one is new to me, and I was amazing how my eye kept trying to twist it into Leonardo's mural. Also, this is so very pre-Vatican II Catholic in the episcopal attitude of the apostles. I muse at the Castilian Christ and in the anachronistic crystal tumbler that reminds me more of the snuff-glass juice glasses of my youth than the equally anachronistic golden chalices of modern consecrations. That foreground is so powerful that the background is almost overwhelmed and yet it is there we truly see Dali's mind asking relevant questions.