Subtotal: $

Checkout

Not Enough Christmas Music

We barely have any Christmas music at all. We have too much Advent music.

By Terence Sweeney

December 9, 2024

It is beginning to sound a lot like Christmas. It’s the time of year when people complain that Christmas music comes too early each year. For some, that might mean moaning about Christmas tunes in shops in late October. But for a liturgically inclined person like me, the time for Christmas music is Christmas, which should really not begin before December 24. Advent – its own season with its own ethos, moods, and rites – has its own music. Thus, I used to gripe that we should hold off on “Jingle Bells” and sing “Creator of the Stars of Night.” But in recent years, I have listened a little more closely and have realized that we barely have any Christmas music at all, early or late. We are a culture with too much Advent music.

Think about it. Few popular Christmas songs are about celebrating Christmas in the present. They are about the longing for Christmas in the future. “I’m dreaming of a white Christmas.” “It’s beginning to look a lot like Christmas.” “All I want for Christmas.” Santa Claus is making lists, checking them twice, and coming to town. But he is rarely actually here. The most beautiful secular Advent song is Bing Crosby singing “I’ll be home for Christmas.” The song is full of yearning for the features of Christmas: “Please have snow and mistletoe and presents under the tree.” Bing croons about how “Christmas Eve will find me where the love light gleams.” But painfully, and beautifully, the song ends by saying that Bing – and the many service members he represents – will be home for Christmas “if only in my dreams.”

We long in words set to music for the Christmas that is to come, even if that Christmas is only in our dreams.

But this is Advent music. Advent is the season of longing. If one prays the Liturgy of the Hours, one will pray the words “Come Lord Jesus” dozens of times a week. Consider the great hymn of Advent “Veni Emmanuel” (O Come, O Come, Emmanuel). We pray, in the darkness of December, that the daystar, the root of Jesse, the wisdom of God will come. Veni, we implore ten times. Most essentially, we ask for the coming of Emmanuel, God-with-us. The music of the season is suffused with a rich sense of the minor key, the tonal quality of sorrow but also of aching desire. We long because we love and because what we love has not yet arrived.

Photograph by Naomichi / Adobe Stock.

While much of popular “Christmas” music lacks the divine orientation of our longing hearts, it is still the music of longing. Even when the music is as ebullient as Mariah Carey’s “All I want for Christmas,” it is still shaped by the desire to have a presence that is not yet present. Adventus, translated from the scriptural Greek Parousia, is the Latin for an arrival or the coming of one expected. The season of Advent is the season when we long for our loves to be present so that we can delight in them as here-with-us. Most of what you hear on the radio is music just like this, even if the presence we yearn for is family, friends, a lover, Santa Claus, or just presents.

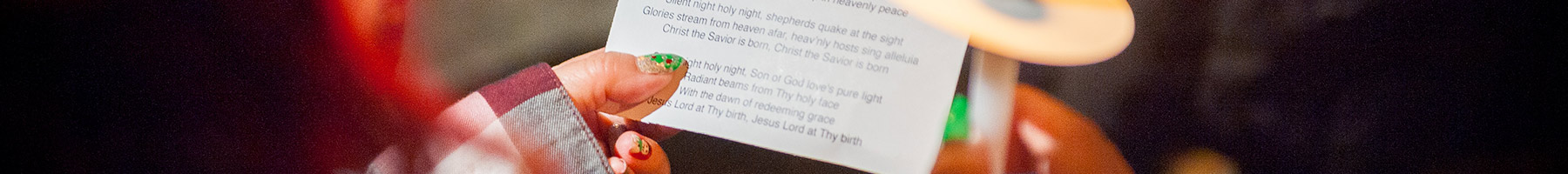

Think of this in contrast to actual Christmas music: “Joy to the World,” “In Dulce Jublio,” “Hark the Herald Angels Sing,” “Gaudete!” When we sing about coming, it is about our coming to adore him “joyful and triumphant.” Why? Because he is there to adore in reality and not only in our dreams. Good Christian men are meant to rejoice. Merry gentlemen are meant to rest in such a way that nothing will them dismay. Even the stiller, darker Christmas songs are joyful. “Silent night, holy night … round yon virgin mother and child. Holy infant, so tender and mild, sleep in heavenly peace.” To hold the baby one has longed for is different than to await the baby one longs for. Christmas music is saturated with joy, with rest in the one longed for, with the presence of our Love and our loves. It is that joy that is missing from most popular Christmas music, and if it is present, it is ersatz or sentimental. Christmas joy is not saccharine. The joy of Christmas music is grounded in the knowledge that Christ was “born on Christmas day / to save us all from Satan’s power / when we had gone astray.”

None of this is to say that I do not like popular Christmas music or music of longing. Advent is my favorite liturgical season and Bing makes my heart swoon each December. To be a Christian is to dwell in that longing to see God’s face and to be in his presence. Likewise, much of our life is lived in longing and absence. There is a place for music about how, despite the pain of giving your heart to someone who gave it away, you still hope to give it to somebody special next Christmas.

The problem with having so much Advent music masquerading as Christmas music is that it leaves us, well, without Christmas music. We are left in a culture of longing without arrival, yearning without joy, a culture that only arrives home in its dreams. This is particularly dire for those who do not attend Christmas services and do not hear the music of joy. Advent music, secular or religious, is music of a heart that is restless. But it’s not to be a permanent state of restlessness; as Augustine says, “O Lord, our hearts are restless until they rest in you.”

We are left in a culture of longing without arrival, yearning without joy, a culture that only arrives home in its dreams.

It is this resting in joy that modern life seems to resist. A liturgical Christmas is the delightfully hard to enumerate season of eight days (it is an octave), twelve days (until Epiphany), a variety of days (until Baptism of the Lord), or forty days (until Candlemas). Meanwhile many non-liturgical Christians gather for one day, the next day return gifts, and then go back to work.

We are too close to Thomas Hobbes’s vision of man, which has so shaped the modern world. For Hobbes, humans have “a perpetual and restless desire of power after power, that ceaceth only in death.” This power is the ability to get what we want. But fundamentally, the ability to get what we want leads us to desire more. Thus, it is longing without presence, work without rest, and consummation without satiety. And so, for Hobbes there is no summum bonum or finis ultimus. There is endless Advent music with no Christmas melodies to be heard. Or as C. S. Lewis puts it in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, endless winter without any Christmas.

Blaise Pascal also observed our restless and infinite desire for more in the ways we seek distraction and power. For Pascal, however, this infinite want was a sign that there is an infinite fulfillment, a perfect resting place that alone can satisfy our tortured hearts. Pascal knew what it meant to only have the prayer “veni” and to only be home in his dreams. But he also knew Christmas. On the night of his conversion, he wrote words on a scrap of paper, words which he then carried next to his heart the rest of his life. At the center of the writing, were the words “joy, joy, joy.” They could be the words of a Christmas song. These words of bliss are the words of a man who knew Advent, who prayed for presence: “Let me not be separated from him forever.” But Pascal also knew the meaning of being “eternally in joy for a day’s exercise on earth.” In other words, the eternal joy of Christmas is promised us after, but also amidst, the short Advent of our lives.

While it is true that our present lives are shaped by longing, there can be no real Christmas if secularism holds sway over our lives. There can only be an Advent without arrival and so only striving in desire without resting in joy. Pascal and Hobbes both knew that a this-worldly life can only be a place of infinite desire with neither finite nor infinite fulfillment. This is a life of only being home for Christmas in our dreams.

That vision is real, but for a Christian it is only part of the story. Our life is an Advent season of waiting, working, and longing. But we can have the hope for joy, and real moments of resting in joy, if we believe in Christmas. We dwell in Advent, but we are not meant to stay in Advent. Advent is the path out of longing and into joy. We can see this even in our Advent music. We sing “gaude,” rejoice, as many times as “veni,” come, in “Veni Emmanuel.” We do not make this journey by pretending there is no longing and darkness. There is a reason we sing Advent hymns in the middle of the long night.

We can make this journey through longing into joy if we believe the first Christmas carol written by Isaiah. To sing his hymn is to know the possibility of real Christmas music – whether sung in church or sung rocking around a Christmas tree or wassailing among the apple trees. Written in longing, Isaiah’s carol expresses the joyful reality of the presence of God eight-hundred years before the nativity of Emmanuel. His hymn has none of the uncertainty of Bing’s being home in his dreams. Instead, Isaiah had the Advent certainty of Christmas joy. The joy that, even in the darkness of December, knows: “For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given.”

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.