Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Insights on Vocation

-

Monks and Martyrs

-

A Love Stronger than Fear

-

Now and at the Hour

-

Icon and Mirror

-

Dirty Work

-

Oh, to Weld!

-

Insights on Work

-

Carl Sandburg’s “Buffalo Dusk”

-

To-Do List

-

Mercenaries out of the Gate

-

Loneliness at College

-

An Economy for Anything

-

The Artist of Memory

-

Poetry and Prophecy, Dust and Ashes

-

Valor

-

Editors Picks Issue 22

-

Carl Sandburg

-

Covering the Cover: Vocation

-

The Noonday Demon

-

Captivated by the First Church

-

Sometimes I Wince at the Weight of your Hand

-

Why We Work

-

Readers Respond: Issue 22

-

Buccaneer School

-

The Unchosen Calling

A Life beyond Self

In her novel Middlemarch, George Eliot describes the “epic life” of Saint Teresa of Ávila.

By George Eliot

October 13, 2024

Who that cares much to know the history of man, and how the mysterious mixture behaves under the varying experiments of Time, has not dwelt, at least briefly, on the life of Saint Theresa, has not smiled with some gentleness at the thought of the little girl walking forth one morning hand-in-hand with her still smaller brother, to go and seek martyrdom in the country of the Moors? Out they toddled from rugged Avila, wide-eyed and helpless-looking as two fawns, but with human hearts, already beating to a national idea; until domestic reality met them in the shape of uncles, and turned them back from their great resolve. That child-pilgrimage was a fit beginning. Theresa’s passionate, ideal nature demanded an epic life: what were many-volumed romances of chivalry and the social conquests of a brilliant girl to her? Her flame quickly burned up that light fuel; and, fed from within, soared after some illimitable satisfaction, some object which would never justify weariness, which would reconcile self-despair with the rapturous consciousness of life beyond self. She found her epos in the reform of a religious order.

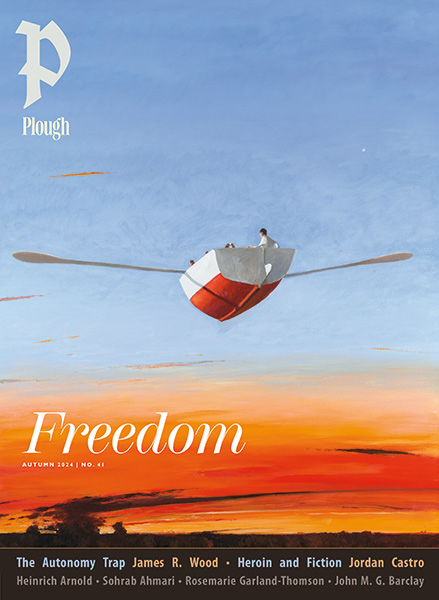

George Harvey, Far from Home, oil on panel.

That Spanish woman who lived three hundred years ago, was certainly not the last of her kind. Many Theresas have been born who found for themselves no epic life wherein there was a constant unfolding of far-resonant action; perhaps only a life of mistakes, the offspring of a certain spiritual grandeur ill-matched with the meanness of opportunity; perhaps a tragic failure which found no sacred poet and sank unwept into oblivion. With dim lights and tangled circumstance they tried to shape their thought and deed in noble agreement; but after all, to common eyes their struggles seemed mere inconsistency and formlessness; for these later-born Theresas were helped by no coherent social faith and order which could perform the function of knowledge for the ardently willing soul. Their ardor alternated between a vague ideal and the common yearning of womanhood; so that the one was disapproved as extravagance, and the other condemned as a lapse. …

Here and there a cygnet is reared uneasily among the ducklings in the brown pond, and never finds the living stream in fellowship with its own oary-footed kind. Here and there is born a Saint Theresa, foundress of nothing, whose loving heart-beats and sobs after an unattained goodness tremble off and are dispersed among hindrances, instead of centring in some long-recognizable deed.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Linda and John wilson

“Middlemarch is one of my favorite books. I have thought a lot about it and over time wrote down some of my thoughts on the book. Here is a bit: Rebecca Mead in her article, “The Gulf Between Aspiration and Accomplishment” writes about the impact of George Eliot’s novel “Middlemarch.” The novel revolves around a character, Dorothea, who wants to make the world better, especially for those whose treatment at the hands of the world has been unkind, cruel, or brutal. Dorothea is not motivated by anything spiritual, but by a sole desire to do good. Mead writes: “Dorothea’s inclination is not to withdraw to a cloister for a life of private devotion, however. Today we might recognize her motivations to be not so much religious as social and ethical: She wants to do good in the world, which in her case is provincial England around 1830. Dorothea wishes to reform the lives of the tenant farmers on her uncle’s property not by improving their souls for the hereafter, but by building them new and better cottages for the here and now. Early in the novel Dorothea marries a clergyman, Edward Casaubon, but her attraction to him is not due to any exemplary faith on his part, but rather because she believes—mistakenly, it turns out—that he has a great mind, and that by participating in a minor way in his intellectual project, she might contribute to the greater good of the world.” At the beginning of this article Mead points out Eliot’s evocation of St. Theresa of Avila (a 16th century Catholic writer and mystic) and compares Dorothea to her. Avila’s influence was profound upon the church and people of her day. The youthful aspirations of the young Theresa are contrasted with those of the young Dorothea. In the course of the novel, we follow Dorothea’s efforts to make the world of her village better, and the lessons the book teaches about those that do make the world better and how they have been received by the world are, I believe, truthful and profound. The book says of Dorothea, “But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.” Mead says of Dorothea“What is important is not the winning of renowned, but the doing of good, regardless of the notice it may or may not bring to the doer of this good.” Thomas Grey pointed out in his “Elegy in a Country Churchyard”: The boast of heraldry, the pomp of pow’r, And all that beauty, all that wealth e’er gave, Awaits alike th’ inevitable hour. The paths of glory lead but to the grave. Known or unknown we share a common end. Some that find their spiritual face, do go on to achieve great notice, but the vast majority go largely unnoticed, even within the congregations to which they belong. Dorothy Day and Mother Theresa are very well known. But the work these individuals began is carried on by many others whose names are relatively or completely unknown. Eliot was not a Christian writer, though she grew up inside the church, and her faith was perhaps compromised by the church hypocrisy she saw around her. But the work Dorothea did outside the church suggests the work that should be done by the church, and for the most part is, though often unnoticed. Some do not read this book because of its length, but I believe it is a journey worth taking. Cordially, J. D. Wilson, Jr.