Subtotal: $

Checkout

The appearance of Rip with his long grizzled beard, his rusty fowling piece, his uncouth dress, and an army of women and children at his heels, soon attracted the attention of the tavern politicians. They crowded around him, eyeing him from head to foot with great curiosity. The orator bustled up to him, and drawing him partly aside, inquired, “On which side he voted?” Rip stared in vacant stupidity. Another short but busy little fellow pulled him by the arm, and rising on tip-toe, inquired in his ear, “Whether he was Federal or Democrat?” —Washington Irving

So Rip Van Winkle emerges from the Catskill Mountains after a twenty years’ sleep to find his little village gone mad for politics. While he had dozed they had gotten rid of their monarch and set up elections. When the confused old codger protests that he was merely “a poor quiet man, a native of the place, and a loyal subject of the King, God bless him!” the crowd erupts in indignation – to hear such two-decades-old political pieties! “A tory! A tory! A spy! A refugee! Hustle him!” It is only after the crowd determines that he is probably a bit soft in the head that he is allowed to resume his rather apolitical, and rather un-American, position as village idler.

The unrecognized native son; the old-fashioned loyalist in an age of new allegiances; the kindly man who stares uncomprehending at partisan divisions; the idler aghast at the destructive powers of industry; the directionless man wishing to carve out a place for himself independent of everyone else’s compulsions; the outsider unencumbered but also unenriched by responsibilities: Rip Van Winkle was all of these things, because Washington Irving was all of them. Irving admitted he was ill-suited for the purposes his nation made much of: colonial expansion, political intrigue, the raising of factories, the running of plantations, the building of navies. He seemed to himself little more than a gentle, meditative observer. But he used what he had to blaze a new path. Before Irving, Americans had written books. But none had ever made a living as a writer until 1820, when publisher John Murray – after previously rejecting Irving’s work – began publishing The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent., which established Irving as a professional writer and made him, in Thackeray’s words, “the first ambassador whom the New World of Letters sent to the Old.” The Sketch Book’s publication was heralded for seven subsequent generations as the birthdate of American literature. Two of its stories, “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” have kept their place in the popular imagination for two centuries, an achievement which at least for chronological reasons no other American can match. But the rest of the book is little known, so much so that Signet and The Modern Library, while keeping the book in print, have changed its title (it has been rechristened The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and Other Stories from The Sketch Book). Readers are often surprised by its contents: it is not a collection of short fiction but is mostly a travel book, chronicling Irving’s wanderings in England. More than that, it is a quiet hymn to the enchantments of history and literature, a guide to how to be a gentleman, a “sentimental education” by example. For those still animated by the author’s ideals – the good life as that of idle, contemplative, preserving, faithful, philanthropic kindness – this book remains a lodestar. And for those who wish to clear in their minds a space for something greater than the internet’s daily ephemeral outrage, it should be more read.

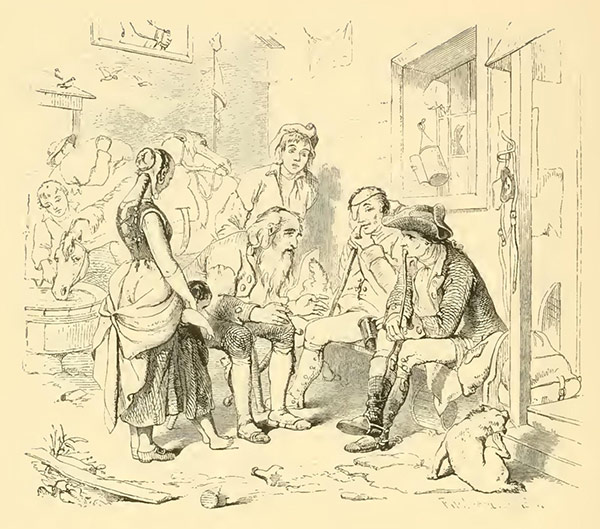

Felix Octavius Carr Darley, Rip Telling His Fabulous Story, 1848

If Irving himself were to wake from his generational slumber into a university English department today, it is not clear anyone would recognize him. There is no doubt that Irving and his Sketch Book have been in retreat for decades now. For cultural literacy’s sake, some high schools might march their students through Irving’s two famous short stories, but Irving’s language is too difficult for an adolescent raised by an iPad. I tackled The Sketch Book after trying Virgil in Latin and Plato in Greek, in the fall of my sophomore year at college. I found a two-dollar copy in the old Miranda Books in Oberlin, Ohio, one of those lovely used bookshops we used to have, fonts of learning now long since gone dry. As I read on the long bus ride back to Jersey, I covered a bookmark with words unfamiliar to me. It was my custom to look up and write down the meaning of every unfamiliar word I met. The Sketch Book was full of them: consanguinity, escutcheon, nosegay, assiduity, flagon, factitious. Compunctious. Rantipole. Thylke. For some familiar words I needed to apply my Latin to understand the subtleties of Irving’s usage, as in this account of fading letters on a gravestone, where monuments (warnings) are differentiated from those stones that still evoke a name: “A little longer, and these faint records will be obliterated, and the monument will cease to be a memorial.”

Indeed, Irving’s prose is classic, almost Augustan; and reading it is like reading classical Latin. Some of the sentences are every bit as long as Cicero’s. For fifteen years after that first encounter in Ohio I read The Sketch Book every October, giving it up just in the last five years under the time pressure of fatherhood. Like many other people I used to read good, complex, artful prose all the time. But if you try it anywhere near the vicinity of a computer you’ll be tempted to give up mid-paragraph and give yourself over to doomscrolling instead. I returned to Irving again this year, after having come to the conclusion that the internet has become a kind of mental disorder. It was absolutely necessary to my proper functioning that I return to the life Irving, following Alonso V of Aragon, so praised: old wood for burning, old wine for drinking, old books for reading, and old friends for conversation. I found myself pleased with the choice. Washington Irving – and The Sketch Book above all – is everything the internet is not.

It is a quiet hymn to the enchantments of history and literature.

There are multiple strands in the tradition we call “the essay.” One of them is little more than reportage: a long, generally nonfictional, story or collection of facts recorded artfully. Another is the essay as literary monstrosity, some kind of bizarrerie or neurosis spun into words, from Alexandrians investigating “what name Achilles had among women” to Nora Ephron obsessing about the size of her breasts. In our half-bored half-dead consumerist condition, these monstrosities make good bank, and if you can hold a reader rapt for fifteen hundred words about the moth dying on your windowsill you’re well on your way to being hailed as a genius. But in its most classic form, the essay is where reason meets emotion or appetite – a kind of negotiation of the terms of our humanity – the balanced engagement with life found from Seneca and Plutarch straight through to Montaigne and Orwell. In its best forms, it is a correction of the monstrous: a continual, sometimes genial, sometimes ominous, sense that some of our emotions and appetites and thoughts are proper and proportionate, and others will lead us to disaster.

This is traditionally the point of an education, the end-goal of which, as Aristotle proclaimed, is “to delight in what one ought to delight in, and to hate what one ought to hate.” Augustine defined the goal as virtue, an “ordo amoris,” where we give our greatest love only to the greatest things, and are most pleased only by what is truly most delightful. This same goal is behind Joan Didion’s best essays as well, where she attempts to buttress what she calls character, “which, although approved in the abstract, sometimes loses ground to other, more instantly negotiable virtues.” The classic idea is that reality has a shape; and our thoughts, emotions, and appetites have to conform to it. We do not put value on things; we have to discover their value; we must find out that looks or fame or money might not be as valuable as we initially thought. This idea is not particularly modern, where the dominant notion is that everyone can make up his own reality, that all propositions of value are constructs. This is of course partially true: our statements of value are constructed hypotheses, which are tested by our own lives. Life renders its own judgement on them eventually. “Can you be righteous,” asks Thomas Traherne, “unless you be just in rendering to things their due esteem? All things were made to be yours and you were made to prize them according to their value.”

C.S. Lewis makes this the theme of his salvo The Abolition of Man, one of the most important books for anyone curious as to why the modern liberal project seems to be going off the rails. Lewis observed that the modern educational system had one primary trick: criticizing and debunking “constructs.” This perpetually dismissive turn was, he held, a betrayal of the purpose of education. What teachers ought to do was to determine which constructs were actually proper and good, and enlist the young in an emotional loyalty to them. Only through the disciplined emotions do good men become good men, and more than just the prey of their basest appetites – a concern more than ever in a consumerist society that has all the data it needs to bind an appetitive chain around any of us:

Without the aid of trained emotions the intellect is powerless against the animal organism. I had sooner play cards against a man who was quite skeptical about ethics, but bred to believe that ‘a gentleman does not cheat’, than against an irreproachable moral philosopher who had been brought up among sharpers. In battle it is not syllogisms that will keep the reluctant nerves and muscles to their post in the third hour of the bombardment. The crudest sentimentalism (such as [modern educators] Gaius and Titius would wince at) about a flag or a country or a regiment will be of more use.

Lewis called students raised on bloodless “critical thinking,” as opposed to a proper education of the sentiments, as “men without chests.”

Why do I bring this up with regard to Irving’s Sketch Book? Because herein – in its enlisting of the emotions in its essay-work – is the great genius of the book. What is so remarkable about Irving is that into the classic molds he poured a river of new Romantic sentiment, and then leavened it all with a humor and proportion that his models lacked. He intersperses his thoughts with his travels, because we all love to hear of distant lands. He does not merely write from his study about the brevity of life; he walks among the tombs of Westminster Abbey. He does not compose an apologia for poetry; he brings his readers to Stratford, to live Shakespeare in situ. By thus playing on our emotions and engaging our appetites, he creates a far more humane impression on us than could be created by a manifesto.

The first essay is entitled “The Voyage,” about the ocean crossing from America. In a memorable series of literary metaphors he describes the ocean as a “blank page in existence” and then continues: “It seemed as if I had closed one volume of the world, and had time for meditation, before opening another.” David Foster Wallace’s 1996 essay “Shipping Out” reads like a suicide note from a cruise ship; Irving’s responses, by contrast, are characteristically measured and appreciative:

Sometimes a distant sail, gliding along the edge of the ocean, would be another theme of idle speculation. How interesting this fragment of a world, hastening to rejoin the great mass of existence! What a glorious monument of human invention; which has in a manner triumphed over wind and wave; has brought the ends of the earth into communion; has established an interchange of blessings, pouring into the sterile regions of the north all the luxuries of the south; has diffused the light of knowledge and the charities of cultivated life; and has thus bound together those scattered portions of the human race, between which nature seemed to have thrown an insurmountable barrier.

Irving’s reactions are sympathetic and proportionate; ordinate, in the old language. Look at the specimen of humane description that closes the essay (forgive its length, but I do love Irving’s prose):

The tide and wind were so favorable that the ship was enabled to come at once to the pier. It was thronged with people; some idle lookers-on, others eager expectants of friends or relatives. I could distinguish the merchant to whom the ship was consigned. I knew him by his calculating brow and restless air. His hands were thrust into his pockets; he was whistling thoughtfully and walking to and fro, a small space having been accorded him by the crowd in deference to his temporary importance. There were repeated cheerings and salutations interchanged between the shore and the ship, as friends happened to recognize each other. I particularly noticed one woman of humble dress, but interesting demeanour. She was leaning forward from among the crowd; her eye hurried over the ship as it neared the shore, to catch some wished for countenance. She seemed disappointed and agitated; when I heard a faint voice call her name. It was from a poor sailor who had been ill all the voyage and had excited the sympathy of every one on board. When the weather was fine his messmates had spread a mattress for him on deck in the shade, but of late his illness had so encreased, that he had taken to his hammock, and only breathed a wish that he might see his wife before he died. He had been helped on deck as we came up the river, and was now leaning against the shrouds, with a countenance so wasted, so pale, so ghastly that it was no wonder even the eye of affection did not recognize him. But at the sound of his voice her eye darted on his features – it read at once a whole volume of sorrow – she clasped her hands; uttered a faint shriek and stood wringing them in silent agony.

All now was hurry and bustle. The meetings of acquaintances – the greetings of friends – the consultations of men of business. I alone was solitary and idle. I had no friend to meet, no cheering to receive. I stepped upon the land of my forefathers – but felt that I was a stranger in the land.

The next essay is about William Roscoe, a Liverpool banker who wrote lives of Lorenzo de’ Medici and Leo X. Irving celebrates Roscoe for his public spirit – Liverpool, like many an American city at the time, was undergoing rapid expansion and Roscoe was one of the founding members of many of its new cultural institutions – and for his fortitude when his business ventures miscarried and his assets passed under the gavel. Irving remonstrates with the people of Liverpool:

I do not wish to censure, but surely if the people of Liverpool had been properly sensible of what was due to Mr. Roscoe and themselves, his library would never have been sold. Good worldly reasons may doubtless be given for the circumstance, which it would be difficult to combat with others that might seem merely fanciful; but it certainly appears to me such an opportunity as seldom occurs, of cheering a noble mind, struggling under misfortunes, by one of the most delicate but expressive tokens of public sympathy.

“What was due to Mr. Roscoe and themselves”! A comment more in line with Lewis – and Aristotle, Augustine, Traherne, and the rest – could hardly be dreamed up. Irving expostulates for what is right, but confesses that he does not have the arguments for it – only the instinctual conviction.

Old wood for burning, old wine for drinking, old books for reading, and old friends for conversation.

The whole book is like this – a three-hundred-page-long meditation on ordinate love. In “The Widow and Her Son,” he expounds on the proper place of the Sabbath as opposed to labor (“well was it ordained that the day of devotion should be a day of rest”) and on “the widow’s mite” (“I felt persuaded that the faltering voice of that poor woman arose to heaven far before the responses of the clerk”). “Westminster Abbey” is the classic Memento Mori essay, greater even than Thomas Browne’s (“a treasury of humiliation; a huge pile of reiterated homilies on the emptiness of renown, and the certainty of oblivion!”). The Christmas essays helped to preserve and transmit old Christmas customs to a world that was forgetting them (Dickens, a true lover of Irving, would take up this task a generation later). “The Boar’s Head Tavern” and “Stratford on Avon” are paeans to the power of poetry to bring joy to human life (“Ten thousand honors and blessings on the bard who has thus gilded the dull realities of life with innocent illusions; who has spread exquisite and unbought pleasures in my chequered path; and beguiled my spirit, in many a lonely hour, with all the cordial and cheerful sympathies of social life!”). “Rural Funerals” is a long meditation on the effect our mortality should have on our conduct: “The sorrow for the dead is the only sorrow from which we refuse to be divorced.” “Where is the mother who would willingly forget the infant that perished like a blossom from her arms, though every recollection is a pang?” “Who can look down upon the grave even of an enemy, and not feel a compunctious throb, that he should have warred with the poor handful of earth that lies mouldering before him!” It concludes: “Then weave thy chaplet of flowers, and strew the beauties of nature about the grave; console thy broken spirit, if thou canst, with these tender, yet futile tributes of regret; – but take warning by the bitterness of this thy contrite affliction over the dead, and henceforth be more faithful and affectionate in the discharge of thy duties to the living.”

Irving had a long and productive career, and his books remain (perhaps surprisingly) relevant to concerns of the day: besides his biography of Christopher Columbus, he wrote a balanced life of Muhammad, and a life of the perhaps now-controversial George Washington. But The Sketch Book is his masterwork. Its miscellaneous nature suited him, so much that he wrote several later pallid imitations of it. It gave him instant fame as one of the greatest stylists in the English language; unfortunately his later prose shows signs of trying to live up to his reputation. In The Sketch Book alone he balanced his involved periods with short, vigorous declarations. And unlike many other such works, the book’s moral compass – for which it was famous – pointed in a direction even moderns would recognize as northish. In the essay on Philip of Pokanoket Irving laments the destruction of Native Americans: “It is painful to perceive, even from these partial narratives, how the footsteps of civilization may be traced in the blood of the aborigines; how easily the colonists were moved to hostility by the lust of conquest; how merciless and exterminating was their warfare. The imagination shrinks at the idea.”

A reader does not have to compromise his or her moral integrity to enjoy Irving; to me, he is the most edifying of all authors. A whole host of (unfortunately) now-almost-risible virtue words hover about his pages: prudence, temperance, fortitude, chastity, kindliness, purity, benignity, charity. He was in many ways a proto-Victorian, and he retained his popularity up through the Progressive Era and World War I. The tide turns here; shortly thereafter Hemingway states that American literature began with Huckleberry Finn, when Twain turned once and for all on “sivilization”; Hemingway was most pointedly excluding Irving. Irving was about edification, about building up character and civilization and a just order of things. More modern artists had other concerns. But it is entirely possible that in an age of rebuilding we will need to look back to Irving.

In the meantime, those of us who love Irving will continue to enjoy him, and to put a copy of The Sketch Book in the hands of those young people just past adolescence, after a failure or two in life, when they realize that they will need a few virtues to get by in this world; trusting, as another Irving appreciator did, that Irving was that most unusual thing, a human being both great and good, and that this particular book “is an expression of the man, and daily converse with it cannot fail to give us something of the beauty, sweetness, and nobility of his nature.”

John Byron Kuhner is editor of In Medias Res, the Paideia Institute's online magazine. He has worked as a Latin teacher, landscaper, maple syrup farmer, and is now fixing up an old hotel in Alligerville, New York.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Chris

Of course, a Christian life will lead to the virtues celebrated by Irving, and real Christianity, apparent by true virtue and the gifts of the Spirit, has been waning since at least World War I. The decline of true religion, and the marriage of a sizable portion of the Christian church that remains with evil (that’s what it is—executions by the state, unchecked capitalism, separating children from parents at the border, racism and intolerance, hate-mongerong, etc), leaves us in a pathetic state. How many Christians actually want a life of virtue? Love your enemies is as alien to the American Christian as all the virtues Irving praises. I know atheists who are far more loving and do more for others than many Christians.

THOMAS CROTTY

I'm not sure about the wisdom of the retired priest, though he has a point. The latin root for both education and seduction, ducere, is to lead, as Mr. Kuhner knows better than I. The question is, where is the teacher leading the student to? I prefer the notion that the best education is a leading of the student out of themselves, and beyond the teacher as well, to something greater than either one, the truth. Beware of the teacher offering a pre-packaged set of truths! And the best education (the best conversation with old friends Irving would perhaps say, the best kind of essay, I think Mr. Kuhner is saying), leads us beyond ourselves, offering models, markers to find our way to the truth in this confusing world, full of seduction and seducers as it is. Call these markers virtues--faith, hope, the greatest being love. The model teacher, I think of Christ here as the model rabbi, teaches a Way that reaches beyond both student and teacher, to a reality worth dying and living for. What a voyage, what an adventure! Thanks to Mr. Kuhner and the Plough for a thoughtful, thought provoking piece.

Chris

‘ education, the end-goal of which, as Aristotle proclaimed, is “to delight in what one ought to delight in, and to hate what one ought to hate.” ‘ ...reminded me of a retired priest who came to speak one night while traveling to a mountain retreat. His discussion was existence beyond life. His view on education was that the goal of the teacher was to seduce you into their point of view. Honest man.