Subtotal: $

Checkout

Rereading Favorite Books

I reread books because I love the story, or the voice, or the characters. And rereading increases that love.

By Grace Hamman

April 11, 2025

Every year during Advent, I reread Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. I have been doing this for over a decade, and had been rereading it regularly for a decade before that. As I have aged, I have even decided other books of Austen’s are superior to Pride and Prejudice. Yet I continue to settle myself down around the first week of December and spend time with Lizzie, Darcy, Jane, Mr. Collins, and the incomparable Lady Catherine de Bourgh. When she was younger, my preschooler really only wanted The Runaway Bunny read to her a thousand times. Over and over, I have recited, “‘If you become a bird and fly away from me,’ said his mother, ‘I will become the tree that you come home to.’” When my eldest was first reading chapter books, she reread The Yellow House Mystery, one of the Boxcar Children books, almost weekly, closing the book with a fulfilled sigh. As she told me, “I love that the mystery is solved and that there’s a happy ending where they all love each other.” They reread those books for the same reason I reread Pride and Prejudice. We love reading, we love those books, we love the people and pictures within them. We, whether two or seven or thirty-six, share this practice.

Love is the starting place of repeated rereading. And because of that beginning, the gifts of reading are amplified within its practice. Let me make a case to you: rereading is a rich, moral craft that forms us as people.

Here’s something funny about rereading: when we reread, it is virtually impossible to do so acquisitively or instrumentally or as sheer consumer. Rereading almost never provides new information or cultural cachet, as reading a new book might. Rereading does not aid the publisher’s goal of making money, as I already own the battered book. Nor does it typically fit into my own plans for new projects. Rereading is an act of resistance against the creeping instrumentalization and monetization of every moment of my time. But that’s not the main point of rereading, just a bonus. Rereading is about formation.

In postmodernity, we have somewhat lost the idea of reading, either repeated or new, as formation. Reading for pleasure or for research does form us, as a process. Yet most of us have reduced reading to acquisition, either of pleasure or information. We approach books as consumers, not as the strange soul-body composite formed by our contexts that we really are. No wonder, then, that we have lost the plot when it comes to reading as formation. Every day, it seems, some bleak new study or essay emerges on how everyone’s attention spans are destroyed, on how fewer people are reading books, on how difficult it is becoming to focus on something longer than a fifteen-second clip. It is just easier to consume, to get some kind of information or entertainment this way.

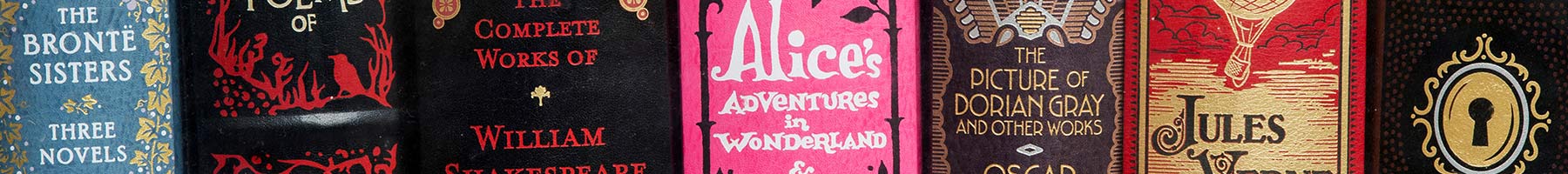

Photograph by Tim Gainey / Alamy Stock Photo.

For Christians in the Middle Ages, reading was a moral activity, ultimately part of shaping the soul and body. Reading does not merely happen in the intellect; it is profoundly embodied. We hold a text, something outside ourselves, in our hands, whether digitally or on paper. We read in certain places, at certain times, as people with particular histories and bodies. Reading takes place in our mind and in our gut, in our emotions, in these bodies. In her magisterial work The Book of Memory, Mary Carruthers writes that medieval Christians believed that “reading is to be digested, to be ruminated, like a cow chewing her cud, or like a bee making honey from the nectar of flowers.” For the moral effects of reading are not necessarily only conveyed through what the author originally intended, but how the text speaks to the reader, how it is considered in light of one’s own life – interpreted, digested.

In other words, this digestion takes place as one’s memory is activated by the text. “Memory is like the mind’s stomach,” remarks Augustine in Confessions. Monks loved using digestion and bodily metaphors for reading. Medieval monastics made hilariously questionable comparisons between what happens when you think after you closely read and what my children politely call “floofing.” The monks encouraged reading during eating, words devoured alongside the food. Food and word facilitated each one’s absorption into the self.

For many medieval writers, memory was activated through their copious memorization of texts. Lectio, basic reading, led to meditatio, deeper meditation over its meaning, letting the book settle into your bones. Memorization was often the preferred way to let lectio become meditatio, and it was the vehicle of moral formation. For these medieval readers, Carruthers notes, “only when memory is active does reading become an ethical and properly intellectual activity.” In perhaps the strangest twist to us in modernity, sometimes even quotation was viewed as a potentially dangerous activity, best practiced only by masters of the text. Carruthers cites Robert of Basevorn, who “reserves the practice of quotation (or ‘cotation’) only to the most learned and skilled of doctors.” The Wife of Bath in The Canterbury Tales, or Paolo and Francesca in Canto V of Inferno, read incompletely to their own costs. To use an author without knowing them well is to excerpt meaning, perhaps falsely or incompletely, to suit one’s own ends.

Memorization has fallen out of favor in modernity, but rereading does something similar. And the books I reread in their fullness taste quite different. Alasdair MacIntyre’s moral philosophy is like a kale salad, requiring much jaw-work before digestion becomes remotely possible. Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop is like a roasted root vegetable, tasting of buried sunlight, reminding me of where I come from in my native Southwest. And Pride and Prejudice has taken on the flavor of mulled wine at Christmas, gladdening the heart in celebration that at last Lizzie and Darcy understand one another. If Augustine is right and memory is indeed the mind’s stomach, what happens to me as I reread and digest this different fare?

Like memorization, our repeated rereading becomes part of us, stamped into our character. As sustenance, it feeds our inner emotional and intellectual lives. And it involves two components: the words and meanings and people in the book in front of me, and myself, my complete self with all my own experiences and thoughts.

Initially, I chose to read Pride and Prejudice during Advent because it is the kind of cozy, happy-ending book that naturally belongs to fireplace weather. But as I read, and read again, Austen’s novel continued to give beyond initial reading: apt indeed for a work originally entitled First Impressions and formulated upon evolving self-knowledge. As Lizzie discovers who she really is – someone who is profoundly prejudiced against people unlike herself, who is prideful in her assumptions about the way the world works – I discovered, to my surprise, that her and Darcy’s transformations fit Advent as well. They belong to the older sense of Advent as the season of penance, of becoming, of cultivating self-knowledge and recognition of need. Such is the kind of recognition that leads to the proper worship of the Christ-child. Of course, I do not think that Austen intended Pride and Prejudice as an aid to penitential meditation. But multiple rereadings opened up themes overlooked in earlier readings. This is part one of the work of memory. The text keeps offering up more of itself, when one comes to it again and again in love.

At some point, fresh insights into themes or meaning may cease. After all, I have now likely read Pride and Prejudice forty or fifty times. But something else happens. Because I have eaten the book like Ezekiel, these characters now live in my memory. In An Experiment in Criticism, C. S. Lewis famously writes, “In reading great literature I become a thousand men and yet remain myself. Like the night sky in the Greek poem, I see with a myriad eyes, but it is still I who see. Here, as in worship, in love, in moral action, and in knowing, I transcend myself; and am never more myself than when I do.”

In rereading, this new-seeing process continues even after the book is shut and reinserted in its proper shelf. In my memory, through long acquaintance, dwell Elizabeth and Darcy, Frodo and Gandalf, Jo and Laurie, and even real-life folks like Thomas Aquinas and Julian of Norwich. I know their words and choices. They echo and speak at odd moments. Simultaneously, I know these characters and writers have little to do with me; the authors were not considering me other than in the abstract when they inscribed their ideas on the page. There are people and happenings beyond my own sorrows and joys. Rereading allows me to give life to and space for their voices.

Which brings me to the other piece of the rereading puzzle: each one of ourselves, our experiences, our individual ongoing projects of interpretation of our tangled and broken desires and thoughts and actions. Rereading tugs upon a chain of memories of the self, not only the memories of the book.

When I reread MacIntyre’s moral philosophy, I marvel at how once I struggled mightily to understand, and now I understand, just a little bit more. I am encouraged that I can change. In returning to Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, I remember my childhood yearning, like the March girls, to help. I remember curiously mulling over the idea of self-discipline, of curtailing one’s desires in order to pursue better things: Jo turning aside from writing easy pot-boilers to harder and more truthful efforts, turning aside from Laurie to Professor Bhaer. As I reread Little Women, I am cognizant of my eight-year-old self, my thirteen-year-old self, and my present-day self. Rereading tethers me to myself through my memories. It reawakens my childlike longing for a life of goodness in a dim and confusing moral world, without returning me to actual childishness. Madeleine L’Engle’s words about fiction writing in Walking on Water are equally true of rereading: “We can, indeed, be eighteen again, and retain all that has happened to us in our slow growing up. I am still in the process of growing up, but I will make no progress if I lose any of myself on the way.”

In its repetition, reading is like liturgy: it tracks time’s work of transformation, which otherwise easily goes unnoticed. Rereading takes the shape of a spiral – it’s not merely me returning to the same book and same place that I was when I read it last; I return and yet remain in my own body now, moving backward and forward in time and space. Augustine writes of time as a “tension,” a “tension of consciousness,” he suspects. In time’s flux each of us are fragmented, until united in eternity. I wonder if in rereading, in memorization, we catch a glimpse of a unity in ourselves that is by no means complete, but a taste of future wonderment, of promised wholeness. Who are we becoming? If we let it, reading can become a mirror into our notoriously opaque inner selves. But such a process does not happen in shallow, quick reading. It only happens when we give books deep attention, the sustained attention of repeated returns.

Rereading ultimately creates something very strange, like throwing a party with absurd and wonderful guests: the quiet presence of my past self at nine, eighteen, thirty-four, and the voices, feelings, and perspectives of the characters and writers that I love.

But in honesty, all these stories make my rereading sound a lot more intellectually coherent than it actually is. In the end, I do not reread primarily for the voices of others, a happy rejection of the monetization of everything, or for the mirror into my soul. Those are all perks. I reread because I love the book, or the voice, or the character. And rereading increases that love.

So, read widely. Read new things. Read things that stretch you in surprising ways and lead you to new voices and fresh insight about the beautiful world. But reread, too.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.