Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Repairing Relationships

-

Not Everything Can Be Fixed

-

Architecture for Humans

-

Yielding to God

-

Salvaging Beauty from the Ruins

-

On Motherhood and Climate Change

-

An Octopus, a Septuagenarian, and a Millennial

-

Ifs Eternally

-

Poem: “Andy Mayhew, Author of the Sonnets of Shakespeare”

-

Poem: “Daedalus”

-

Letters from Readers

-

My Liberal Arts Education in Prison

-

One Parish One Prisoner

-

What’s a Repair Café?

-

Analog Hero

-

The Sacred Sounds of Hildegard of Bingen

-

Covering the Cover: Repair

-

Could I Do That?

-

Who Can Repair the World?

-

Rebuilding Notre-Dame Cathedral

-

Why Serve?

-

In Praise of Repair Culture

-

Just Your Handyman

-

To Mend a Farm

-

The Home You Carry with You

-

Heaven Meets Earth

-

Portraits of Survival

-

Hunger

-

Three Pillars of Education

-

The Joy of Mending Jeans

-

Zero Episcopalians

Making Art to Mend Culture

Creative art is about imagining the future as it could be.

By Makoto Fujimura and Susannah Black Roberts

December 5, 2023

In this interview, Plough’s Susannah Black Roberts asks artist Makoto Fujimura about culture care as an antidote to culture wars.

Susannah Black Roberts: In your writing about your art and the work of culture care, you’ve focused on the idea of generativity. What is the relationship between generativity and repair? Can you talk about your distinction between “fixing” and “creating,” both in theology and art?

Makoto Fujimura: Yes, repair can be generative, but only if we first learn to behold the fractured pieces to be beautiful in themselves. In a Western industrial mindset, what is broken, what is imperfect, must be “fixed” to be without flaws, or be discarded. In my recent book Art and Faith, I focus on Jesus’ post-Resurrection appearances. He not only came back as a glorified human being who has carried our sorrows and transgressions onto the cross, but he came back as a wounded glorified human being! That is counter to the Western notion of “fixing.” The post-Resurrection, glorified wounds of Christ can open theology up, and bring art and culture-making into a new vista.

Your father worked in the field of linguistics and computing. You seem less hostile than many artists to large language models and other artificial intelligence. But your respect for the uniqueness of human creativity must put you at odds with some applications of visual AI that can supposedly create art. What are your philosophical, theological, and practical assessments of these new technologies?

I grew up in the famed Bell Labs community in Murray Hill, New Jersey, so I perhaps have a different vantage point into technology than other artists. In the early seventies, Lillian Schwartz created computer-generated imagery, and Max Mathews created an early sound instrument machine that is now the “Max” audio simulation software still used today. What I see now is simply a huge development in pattern-matching abilities by supercomputers since these early experiments. But machines are not (yet) “intelligent,” so artificial intelligence is not a true descriptor of what is happening. I see the ChatGPT phenomenon as only an extension of the pattern-matching abilities that allow machines to collect and collate billions of data, without having judgment or aesthetic skills. One can input those discernment skills, but then we are using the machines as tools, just as I can use a paintbrush as a technology, as a tool.

We have been given enormous power to either create a generative abundance of shalom or to destroy the world multiple times over. Of course human creativity and technology is dangerous – we can visit Hiroshima or Nagasaki to experience the extent of such destructive powers. But we have also been given the ability to discern, to correct and steward such powers. Art serves to train the imagination to seek the future, not just on this side of eternity, but, in mysterious ways, on the other. New creation does not happen fully without our making (just as the Eucharist does not happen without bread and wine). Therefore, artists and Christians are futurists; our task is to create the future that ought to be. So the question is: What are we making? What can we create today that sanctifies our imaginations, rather than uses our imaginations to seek power and destruction? I have stood on the Ground Zero ashes in New York, pondering Hiroshima and Nagasaki. My art has been a way to explore the impossibility of this pondering.

Some people claim we live in a society that is more hostile to Christianity than in the past. As an artist and a believer, how do you respond to hostility in the culture? Is it too late for what you have called “culture care”?

In the nineties, any idea of transcendence, or even to speak of the foundations of truth and goodness, was considered tenuous, if not a threat to the established notions of relativism. In the art world, “beauty” was taboo. If you identified yourself as a Christian and created beauty, as I did, you were immediately branded as an “outsider” threat to the mainstream.

Tim Keller helped me to understand that even in shark-infested waters, we are to create beauty in the midst of a despair-filled city. The idea of “culture care” is to seek to love culture as an exile in the “Babylon” we are called to serve. Culture care is a nonviolent antidote to a culture-wars mindset where scarcity rules in fear. Culture care always seeks to plant seedlings (as Jeremiah 29 tells us to do), even in Ground Zero ashes, so that future generations will find the city, once at enmity with the gospel, now prospering because of the faithful making journey of her children. To live out culture care is to live generatively, and to create in the “fruit of the Spirit” of Galatians 5. It has always been a task for Christ’s followers to do so, even in hostile, exilic lands.

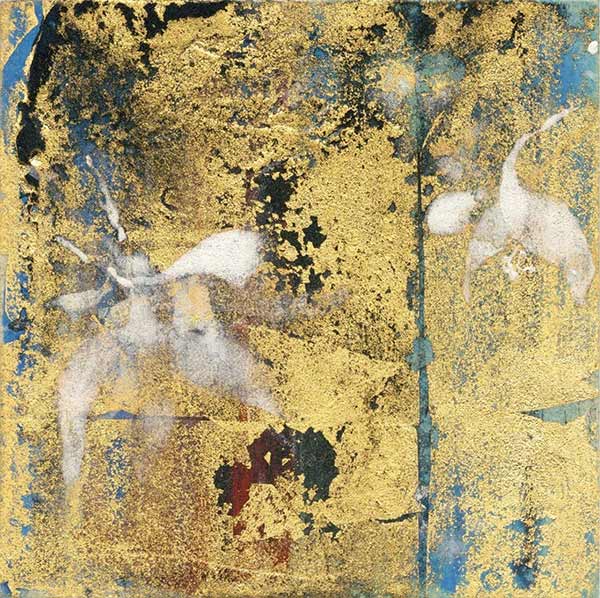

Columbines – Study, mineral pigments and gold on kumohada paper. Artwork copyright © 2010 Makoto Fujimura. Used by permission.

Relatedly, we are often said to be in a culture war – the term coined by James Davison Hunter and now run with by many self-appointed culture warriors. You have addressed this directly, contrasting the approach of culture war with culture care. It feels as though the temptation to war is increasing: How can we understand the work of culture care in the face of this temptation? Is there a way that culture care can respond to the increasing polarization of our time? How can culture care help promote the common life that is crucial to the political common good? Can it pull together something beautiful out of fragmentation, as a kintsugi-mended tea bowl might?

When James Hunter coined the term, he was not endorsing culture wars, but was observing, as a sociologist, that such a divisive discourse would significantly damage democratic discourse. His book Culture Wars was indeed prescient, and we are reaping the poisonous weeds of these wars many years later.

Yet imagine the desperation of those living in first-century Palestine, in the regions where Jesus grew up. Were they fearful? Were they threatened? Yes! There was no guarantee for tomorrow, no stability to speak of for Joseph and Mary. Yet Jesus taught us to love our enemies. To make art is fundamentally to “look at the birds of the air” and “consider the lilies” – and that is a command by our Savior from the same Matthew 6 – as opposed to being anxious about what you wear, eat or drink.…Art may be a way to “love our enemies,” as that is the most “transgressive” act in culture.

Historically, in first-century Nazareth, or sixteenth-century Japan, or the civil war that ravaged nineteenth-century America, people had it far worse in terms of the terrible enmities of cultural division. Christians are always asked to love with courage in divided lands and tribal conflicts. Kintsugi (flowing out of the sixteenth-century Japanese feudal war period) is a fine metaphor, as we have seen it employed frequently in recent times modeled in pop culture, from Ted Lasso to Star Wars. In kintsugi, we are to “mend to make new” rather than “fix,” to make the fractures more beautiful by first beholding them, and then to use Japanese lacquer and gold to accentuate the beauty of fractures, rather than hide them. As the broken body of Christ, the church must lead in the way of modeling such mending to the fractured, suffering world. We are to value people and their differences, each with a unique journey of brokenness. We must remember that we as Christians are a mosaic of broken pieces, only coming together in Christ. Art dedicated to kintsugi generation can be the bridge to invite skeptical folks into an authentic community of brokenness, only made beautiful by our kintsugi Savior.

In the face of what many experience as both the ugliness and unrootedness of our contemporary culture, people often express a longing for beauty. How can art help address this hunger for beauty and rootedness? Can it create a people that includes Christians and non-Christians, red and blue state Americans, old and new immigrants – a cultural and political yobi-tsugi mending?

Yobi-tsugi, an extension of kintsugi that intentionally brings fragments of different sources together in a mosaic, is a powerful metaphor for our future.

First, we need a realignment of our understanding of beauty beyond a Western, industrial, cosmetic, immaculate-perfection concept toward that of a maculate, broken beauty of the East. The divide in ideology, both on the conservative and liberal side, has roots in the binary “scapegoating” of what we see as unforgivable imperfections. We see such fractures only through the immaculate lens that our ideological idols demand.

Art can bring somatic, reflective, deeper contemplation that moves us away from blaming others (or any politicians) to asking instead, “What is in me to mend, to make new?” When we do that, when we behold deeply of our own souls and the edges of our fractures, we will find that we need each other and communities (even our enemies) to find complete healing.

This interview was conducted on September 10, 2023, and has been edited for length and clarity.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.