Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Let Brotherly Love Remain

-

Take Up Your Cross Daily

-

The Bones of Memory

-

Poem: “Sunrise and Swag”

-

Poem: “Poland, 1985”

-

Church Bells of England

-

Editors’ Picks: Walk with Me

-

Editors’ Picks: Shakeshafte

-

Editors’ Picks: The Least of Us

-

Letters from Readers

-

Celtic Christianity on Iona

-

The Catherine Project

-

Mercedes Sosa

-

Covering the Cover: Why We Make Music

-

Music and Morals

-

The Death and Life of Christian Hardcore

-

Vallenato Comes Home

-

Does Political Music Change Anything?

-

Adventures in Americanaland

-

Music, Memory, and Alzheimer’s

-

Why We Make Music

-

Doing Bach Badly

-

Dolly Parton Is Magnificent

-

Go Tell It on the Mountain

-

Reading the Comments

-

In the Aztec Flower Paradise

-

The Strange Love of a Strange God

-

Is Congregational Singing Dead?

-

In Search of Eternity

-

Violas in Sing Sing

-

Hosting a Hootenanny

-

How to Lullaby

-

How to Raise Musical Children

-

How to Make Music Accessible

-

Chanting Psalms in the Dark

-

The Fiery Spirit of Song

-

The Harmony of the World

The Tapestry of Sound

Hildegard of Bingen meets Yuri Gagarin in the music of a Grammy Award–winning composer.

By Christopher Tin

March 15, 2022

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

Based in Los Angeles, Christopher Tin is a composer of music for the concert hall and for film and video game soundtracks. His song “Baba Yetu,” a setting of the Lord’s Prayer in Swahili, was the first piece of music written for a video game to win a Grammy Award. Plough’s Joy Clarkson spoke with him about themes that bind many cultures together: the fear of death, the need for rebirth, and the desire to fly.

Joy Clarkson: Your music is very international. You draw on many source texts and write in many languages. How did this love of cultures and languages become central to your music?

Christopher Tin: I’ve seen a lot of the world. I was very lucky in that my parents love to travel and they trotted me along with them everywhere. I’ve met a lot of people, tasted a lot of different cuisines, and heard a lot of languages over the years. My music comes from a basic love of experiencing and seeing the world. But there’s also a love of history.

At university and as a postgraduate, I majored in English and music. I was very interested in the history of ideas, the history of thought, aesthetic trends, intellectual and philosophical trends, how they feed into each other, and how every generation of artists and philosophers builds upon the work that their predecessors laid down. I get excited by things like that. I get excited by the interconnectedness of people and cultures and traditions across the world, but also the interconnectedness of ideas through the centuries. I just find that really interesting, and I write about what brings me joy. And that tends to be historical and cultural things.

My first album, Calling All Dawns, contains twelve songs in twelve different languages. It is all about life, death, and rebirth. The source texts pull on everything from ancient myths, to prayers, to some original texts. The album weaves all these together to create a story, a monomyth as Joseph Campbell would call it. It’s a monomyth about how we are all connected by a common human experience that sort of winds through each of our lives like a thread. Taken together, all of our experiences around the world form this elaborate tapestry of humanity.

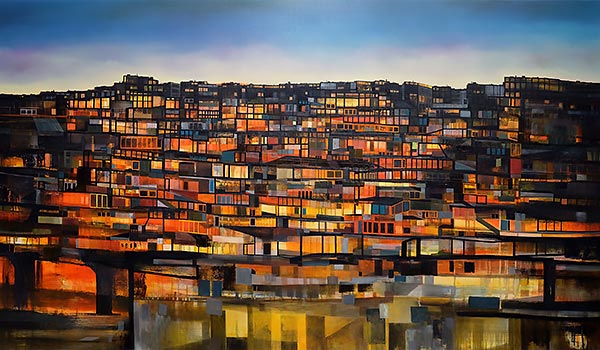

Sim Chan, TwinklingCity no. 6, oil on canvas, 2017 All artwork by Sim Chan. Used by permission.

The theme of tapestry seems like a key concept in your music. Is that true?

Totally. Even the way that I write my orchestral parts and my choral parts relates to this idea, this synecdoche, of a tapestry. I very much think of an orchestra as a series of individuals who play one note at a time. And yes, there are instruments that will play chords, multiple notes at a time, but I tend to think of everyone as a thread. And when I compose my pieces, these threads move in parallel, they move in counterpoint, they intertwine, they spread out, they come together, they split, they join, they do all these different things. To me, a piece of music is a bunch of moving horizontal threads that just kind of fly around in the air and tie themselves together. That’s how I think of music. I don’t think of it vertically; it is the horizontal motion of individual voices or instruments moving through time, being aware of each other, connecting with each other, and all moving toward the big finale.

A really good example of this musically is your album To Shiver the Sky, which intricately interweaves themes, motifs, and voices. That album is ambitious: an eleven-movement oratorio about the history of mankind’s quest to conquer the heavens, a history of aviation told through music. In doing that, you draw on the words of significant figures throughout history. Why did you start that album with a text from Hildegard of Bingen?

I chose Hildegard of Bingen because I wanted to establish the narrative arc of To Shiver the Sky. It’s all about achieving flight, and being up amongst the sky and the clouds and the stars. Long before we were actually able to achieve flight, the concept of being closer to God meant that we did things like build giant cathedrals. The spires went higher and higher, so that we could reach upward toward God. And this was a sentiment to which I wanted to allude early on in the album. Our desire to fly is not just an engineering thing. It’s also for religious reasons. We want to be elevated. We want to be close to God.

Hildegard obviously has a lot of writings, but she’s a composer herself as well. I wanted to write something that sounded like something that she would’ve written, which is why her song is constructed as a plainchant. But I wanted to dress it up with twenty-first century orchestrations and inject it with my own personal style. Because all of this needs to be pulled together under one sonic umbrella and that umbrella is my personal aesthetic taste. So Hildegard’s movement really kicks off the journey, but I also bring Hildegard’s theme back at the very end of the album. We end with a one-two punch: Yuri Gagarin’s first words when he returned from being the first man in outer space, followed by John F. Kennedy’s, “We choose to go to the moon.” The “We Choose to Go to the Moon” movement kicks off with the same melodic line as the Hildegard of Bingen movement, because everything needs to be sort of bookended, in my mind. And the way you do that in music is you transplant motifs from one piece to the other.

Sim Chan, TwinklingCity no. 2, oil and luminous paint on canvas, 2015

We might assume in our modern world that the moon landing was primarily an achievement of technology, but by tying Hildegard’s theme in with JFK’s you remind us that the desire to fly is reflective of a more universal desire, present not just in different cultures, but throughout time: the desire to transcend ourselves, touch the sky, to be close to God.

Yes, they’re hundreds of years apart, but the basic human impulse is the same. A lot of my music focuses on this notion of synecdoche: the part reflecting the whole. I like to zero in on a piece and have it be a microcosm of the rest of the album. One example of this is my Japanese song, which is track two on Calling All Dawns, “Mado Kara Mieru.” In itself it is a miniature cycle embedded into this much larger cycle. And that piece itself is built around this idea of seasons, which is obviously a cyclical sort of thing.

It’s like a Russian doll! It reminds me: Hildegard talks about microcosms and macrocosms. She thinks of human beings as microcosms of the universe. If we want to understand the universe, we look to human beings. And when we look to human beings, we understand something about the universe. To understand the infinite, we look to the finite.

That is, in essence, the title of my second album, The Drop That Contained the Sea. What you just said mirrors, almost perfectly, the Sufi concept that, just like every single drop of water contains the essence of the entire ocean, each individual contains the essence of all humanity. And here we have another example where these parallel thoughts are independently arrived at by a German mystic in the twelfth century and Sufi philosophers.

I think that’s the brilliant thing about music in a way. It shortcuts a lot of these cerebral processes that we all have and just gets you to the good vibes, without really having to work it out in your mind, like, “Why does this delight me?” Oh, it’s not just because this motif recurs in movements four and eleven or whatever. It just does. And you get the joy out of it.

This interview from November 22, 2021, has been edited for clarity and length.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.