Subtotal: $

Checkout

Trumpet Man

A mystery man sporting a salt-and-pepper afro blew a golden trumpet in the prison yard. His tune took me back to the streets.

By Robert Lee Williams

December 14, 2024

It was a sunny spring afternoon in the prison yard. As guys jogged, cuffed dominoes, and bowled bocce balls, a mystery man sporting a salt-and-pepper afro blew a golden trumpet. The tune he was playing took me back to the streets.

Back in the early 2000s, I was a hungry young hip-hop producer and songwriter. Living in a small city in upstate New York, I was chasing a lifelong dream in the Big Apple. The rich soul of the trumpet reminded me of crowded subways and ragtag bands, and stepping off the train to head to the next studio session.

The smooth melody was far from what I was used to hearing: schizophrenics shouting, gates clamoring, bells ringing, prisoners gossiping, keys jangling, boots thumping. In a maximum-security prison, finding pockets of peace can be difficult. I wondered how this man could play his music in a madhouse.

As Trumpet Man fiddled with a valve, I sat beside him and introduced myself. We dapped it up. He told me his Muslim name was Ummah. I was familiar with its meaning. In Arabic, Ummah, roughly translated, means the community, or congregation.

When I told him my name was Kush, he gave me a funny look. There’s a strain of marijuana called Kush, so I quickly clarified its meaning by quoting a bar from the NAS song “I Know I Can”: “There were empires in Africa called Kush.”

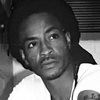

Andre Shobey, The Trumpet Man. Used by permission.

He smiled through the scruff of his beard. The sheet music propped on his trumpet case looked odd until he slid his bifocals to the bridge of his nose, revealing clouded-over eyes. He had glaucoma and had created his own custom notation that was easier to read.

I told him I was a journalist, and I wanted to write a piece about him. I asked him the name of the song he’d been playing. He said it was Louis Armstrong’s “What a Wonderful World.” I opened my pad and picked up my pen, and learned his life was anything but.

Currently serving a sentence of forty years to life, the sixty-five-year-old trumpeter has been playing for more than thirty years. Ummah was born in the Bronx as Andre Shobey. His mother suffered from mental illness and alcoholism; she was unable to take care of him and his six siblings. She ended up in an institution, and he ended up in foster care in Rockland County, New York at a school that housed two hundred boys of varying ages. He described it as a convent with no nuns.

“I was just a little Black kid from the Bronx. I walked into church, with all those statues, stained glass, pictures of saints and angels, and none of them were Black. I was like, ‘Where the hell am I?’” he said.

Ummah yearned to reunite with his family. He would run away on the highway, hitch a ride, and wind up in New Jersey, before finding his way back to the Bronx and looking for his siblings. George, his oldest brother, was the only one he ever managed to find.

Eventually, he’d make his way back to the school, pulled by its siren song. The school had a marching band, where Ummah learned to play instruments. A musician used to come in to teach. Ummah started with the bugle. He learned breath control. Soon, he graduated to the trumpet.

Every year, the marching band played in the St. Patrick’s Day Parade. It was a big thing for the boys. They loved it.

After aging out of the school in the 1970s, Ummah went back to live with his mom, who didn’t have the money for her medication. Desperation led him to committing robberies to support her drug habit, which eventually led to probation, and prison.

“I had an uncle that played the trumpet and piano, he was crazy, too,” he said, laughing. “Never heard anyone play a piano as good as he did. I think crazy run in my blood.”

I could relate. My pops, Charles Williams, was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, but unless he was off his meds, it wasn’t noticeable. He was super laid-back, known for his vast record and CD collection.

I was a troubled adolescent, but I remember the times we’d watch basketball in the living room, jazz crackling on forty-fives. Pops mastered the art of chill. On St. Patrick’s Day in 2018, we buried him.

I miss his music. I miss him.

Hearing the Trumpet Man reminds me of the more pleasant moments growing up. I can’t remember many, and there aren’t many in prison, but when he steps out and blows in that horn, he creates those moments for us.

Once I cut past a group of older prisoners, and Trumpet Man’s tune changed to something rich, somber, and soulful.

“Yo, you don’t remember that?” an older prisoner shouted, a smile plastered on his face. “That’s … that’s from Sugar Hill.”

The music started him reminiscing. Then all of them started telling stories about their neighborhoods. Transported back on to their blocks in Harlem, Bronx, and Brooklyn, they were grabbing two-piece snack boxes, rocking old-school fashions, and ogling neighborhood girls who never gave them the time of day.

I feel bad for roping Trumpet Man into a conversation. I may be interrupting him from sharing a pleasant moment with others, and I’m stealing him from that place where the music takes him. He plays to distract himself from the past. And the present.

The horn gleams as he plays under the sun. When he blows into it, he’s no longer a prisoner. “I’m locked up,” he had told me. “I accept that, but I’m not going to be miserable. Music takes you out of here.”

I can relate to the need for an escape.

In 2009, I was dating a girl named Anna. Her smile lit up my life. One night, we went out to a club, drank too much, and danced to the music for hours. On the way home, we got in a fight that turned violent, and we stabbed each other. She died. I went to the trauma unit, then prison.

Everything Anna and I did involved music. I couldn’t listen to any hip-hop or R&B for a long time after that. If the song had been in rotation when we’d dated, cruised, shopped, or made love, every note made me think of her and miss her terribly. In some ways, Anna took music with her when my actions sent her from this world.

When afternoon recreation was over, we lined up outside an open door and waited for the correctional officer to call us in. Two guys walked in ahead of Ummah and quickly cleared the metal detector. Ummah placed his open instrument case on the table. A guard with a ponytail told him to stand off to the side. She prodded through his instrument and case, scrunching her brow in disgust. “Is he even allowed to have this thing?” she asked the sergeant.

This is the only prison where they’ve given him a hard time. Corrections doesn’t offer us much. Three lukewarm meals, a mattress thin enough to cause back problems, antiquated vocational programs. Why do they want me to learn how to fix a lawnmower? Thankfully, we’re allowed instruments, but Ummah is always careful when he heads through these checkpoints. If the wrong guard is there or one of them is having a bad day, things can go left.

A few Saturdays later, I watched the same guard who had given him a hard time. She was sitting outside, legs crossed, thumbing through a booklet. As Ummah’s horn crooned John Lennon’s “Dreamer,” she nodded along almost imperceptibly, more at ease than I’d ever seen her.

Ummah wants to start a band here, but the administration is dragging its feet. Over the years, he’s played in bands in some of the most notorious prisons, like Attica and Green Haven. He told me if the administration doesn’t let him start a band at Sullivan, then he’ll request his counselor put him in for a transfer to Sing Sing, only an hour up the river from the city, where there is a robust set of music programs.

He also wants to get “Music on the Inside” in Sullivan, a program directed by renowned jazz musicians Alina Bloomgarden and Wynton Marsalis. It links prisoners with professionals who come in and teach them how to play, like the guy who used to go into St. Andrew’s and teach the boys in the band.

In 2021, Ummah had to get rid of his trumpet. He had soldered a hole in it, and for a long time, no one said anything about it. But then, one correctional officer made a big deal about it, saying the trumpet was altered, which is against the rules. Ummah called his longtime friend David Rothenberg, founder of the Fortune Society. He put Trumpet(less) Man’s plight on his radio show, and someone answered the call. Soon, Ummah had a brand-new Andreas Eastman, a quality model to help him spread his peace-magic.

One time in his cellblock, two guys squared up, about to throw blows. Ummah got up on the gate and started playing Bob Marley’s “Redemption Song.” They ended up backing down and apologizing to each other.

“In twenty years of playing in these prison yards,” he said, “never been a fight when I was playing my horn.”

Despite our many conversations, Trumpet Man is a bit of an enigma. I wanted to ask him why he was in prison, but I’m scared that finding out will diminish the moment.

In my writing, I own why I came to prison. For me, it’s cathartic to release that burden. But I always grapple with whether I should include the crimes of people I write about. If it’s relevant to the theme of the piece, then I do. There’s also the curiosity of the reader. While I face the music on the page, Ummah faces his horn and extends his soul into the darkening sky. His sweet melodies lift us out of this big house of pain, to a safe space where we can find a little slice of peace.

In June, the smoke from Canada’s wildfires made the weather uncharacteristically cool.

After not seeing Ummah around the yard for a while, I was happy to catch him perched on the stone table by the pull-up bar, ballooning his cheeks on the mouthpiece, preparing to do his thing. I walked up and greeted him, then kept on walking to the field. I could tell he wanted to be left alone with his art.

When I heard him play Bob Marley’s “Is This Love,” I was filled with joy. I spun around, thrust my fist in the air, and shouted, “Ummah, for the congregation! For the people!”

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Ann Catherine Dayton

Ah! the power of music to lift the soul, even in the most grim of environments. Thoroughly enjoyed reading this life affirming article. Thank you for that little glimpse into the dark world of prison life.