Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Mother Peregrine

-

This Too Shall Pass?

-

A Time for Regeneration

-

The Hard Work of Conversion

-

Tinned Fruit in Times of Famine

-

Floodplain

-

When the Church Doors Close

-

The Pilgrims’ Mark

-

Grateful for Each Breath

-

Care, Pray, Trust, Obey

-

Uncanny Homes

-

Schooling Hope

-

When the Sickness Is Over

-

The Home Is the School

-

Grieving Alone, Together

-

The Art of Dying

-

Scraps and Ruins

-

Clean House

-

Psalms for the Sick

-

The Book of Repose

-

Breaking the Fast in a Broken World

-

Sister of the Four

-

Remember When...?

-

The Rawness of the World

-

Precious Friend: What’s Your Victory Song?

-

The Abomination of Desolation

-

Philip Larkin’s “The Trees”

-

Shutdown Hospitality

-

Rejoicing in Apocalypse

-

By the Lights of Brush and Night

-

Learning to Stay

-

Apart Together

-

A Pain in the Navel: Letter from Bogotá

-

The Eternal Questions Illustrated

-

Fellow Feeling in a Crisis

-

Of Ducklings and Baby Fish

-

Service from Suffering

-

Patience in Lockdown

Serving my first parish in North Myrtle Beach, South Carolina (where Vanna White was in my church youth group, but that’s another story), I read Barbara W. Tuchman’s A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century (Random House, 1978). It only took four decades before that book became relevant for my ministry. Tuchman follows a medieval family through an age when the European world fell apart. One chapter says it all: “‘This Is the End of the World’: The Black Death.” Plague changed the course of history, leading medieval Europe to widespread, agonizing self-examination, dramatic penitence, and some major mistakes. Entire cities wiped off the map, a generation lost, economies destroyed, bloody Crusades. What have we done to make God curse us? The world as we know it is ending.

As we shut our doors and isolated, praying that Covid-19, angel of death, would pass over, I thought of A Distant Mirror. I heard lots of blaming, denying, and a modicum of recognition that deep American inequalities have been exposed, all made easier to swallow by saccharine, syrupy sentimentality: “We are all in this together,” and “Our social isolation is a time to reflect, and to focus upon the love of our families.”

Contemplative isolation is easier if you can afford it. Only twenty percent of African Americans have jobs that enable work from home. The person who gazes at me from behind the glass at the supermarket would give anything not to be forced to be serving me. Though I’m asymptomatic, I could still be her executioner. Not much togetherness in that.

Unlike the fourteenth century, I’m hearing little self-examination, and no penitence. The president is not the only one who refuses to apologize. We’re not medieval, after all. Victims, not perpetrators. The evening news is a litany of death and disappointment, political clowns in high places, bureaucratic screw-ups, all set right with a concluding sappy sermonette about a little girl who gave a thank-you note to the nice lady who delivers Grubhub. Put a teddy bear in the window. Show that you love me by keeping your distance. Text somebody who’s trapped in a nursing home; you’ll feel better for it.

That’s the best that the evening news has to offer. Can the church say better?

Sermons Ruined

“Life as we know it has ended.” Never again will we shake hands.

“A whole generation of students is having the future pulled out from under them,” I heard a faculty colleague say. The sky has fallen, the world is over, though not in a fourteenth century way. Still, gloom’s got more to commend it than the little girl’s note or the teddy bear in the window.

“In about two weeks, a damn virus has destroyed a year’s worth of my sermons,” groused a preacher friend at the beginning of the pandemic. “They lapped up my January homily, ‘Finding Meaning in Marriage.’ Sounds like crap now that it’s the end of the world.”

Who cares about sermons on zest for your daily work, a reason to get out of bed in the morning, or a positive attitude toward your coworkers when you are hunkered down in fear, out of work, and too terrified or broke to dare a trip to Harris Teeter?

“With the United Methodist General Conference cancelled, what do you think will be the future for Methodist schism?” I was asked.

“I’m in the high-risk age group,” I replied. “It could be toxic for me to hug one of my grandchildren, much less to get close to another Methodist. Covid-19 has taken all the fun out of church politics.”

“This pandemic is the most determinative event of this century,” pronounced a news commentator. I’m doubtful of that claim because I read the Bible. Plagues, wars, famines, genocides, and tyrants making misery among the poor are standard biblical fare. More importantly, after a first-century Jew was tortured to death and then resurrected, returning to his betrayers and compelling them to go tell everybody the news about God, Christians have an odd idea of news. A virus can’t change the course of human history as much as God already has.

Disaster makes theologians of us all. Dr. Fauci can tell you the cause; only theology can say why. A pandemic is a prompt for preaching. Any word from the Lord?

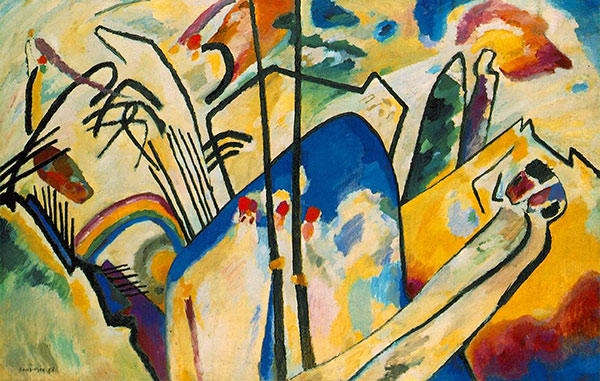

Wassily Kandinsky, Composition IV (Public domain)

Inappropriate Sovereignty

Lately I’ve been thinking about Karl Barth, great theologian of the twentieth century, preacher during both world wars. Back during Barth’s first days as a small-town pastor, he picked up the newspaper and read a statement signed by his most revered professors, all stepping into line behind the Kaiser. Young Barth was aghast, not only at Europe’s plunge into war, but also because of a dumbfounded church.

In an instant Barth saw that the theology he had been taught at the university – all that psychological pap about the “inner Jesus” who gets us in touch with our feelings and connects with our existential anxieties – wilted. Then and there Barth began to work on what was to be his bombshell of a book, The Epistle to the Romans (1918). Preachers know less about current events, the future course of history, or our true inner motivations and feelings than we know about the relentlessly revealing God who meets us in Jesus Christ. What God may be up to in the here and now is so much more interesting than either our anxieties or the Kaiser.

That’s why Barth never mentioned the war in his wartime sermons. Though he believed the war to be both a disaster for German culture and the just wages for nationalistic sin, he repeatedly preached on the privilege to be living in “a unique time of God.” His message to his little congregation speaks also to us today: God has thrust us into an exceptionally apocalyptic age of unveiling in which the folly of our Promethian myths are self-evident and our dependency upon God is undeniable. In a world of lies and disinformation, God has given us not only the way and the life but also the truth – Jesus Christ. It’s our duty to hand it over. If God is not the one who meets us in Jesus Christ, if Jesus Christ is not Lord, there’s no hope. Rather than talk about a return to normalcy, or how the economy would dig out of this disaster, Barth asked, in effect, “What’s a gracious God up to in this unique time and how can we hitch on to what God is doing?”

Just three decades later, now as a professor in Bonn, Barth watched the German church step into line behind National Socialism. One imagines the reasoning: We may not approve of everything the Nazis say and do, but the oppressed German people have spoken. Church is where we come to lick our wounds and overcome our trauma so we can step up and do our bit to help make Germany great again.

The German Christians were the ugly result.

Anybody can see why Hitler was a threat to everything that Christians hold dear, said Barth. More difficult is to see how idolatry, failure to worship, confusion of German culture with Christianity, and timid, liberal biblical interpretation made National Socialism possible. Most difficult of all is to see the church as God’s answer to what’s wrong with the world. The church is called to be a showcase of what God can do, a people who tell the truth that the world can never tell itself. The truth cannot arise from within us; truth must come to us. Truth is a person with a name, an external address to us, an invitation to come forward and be part of God’s grand retake of history – Jesus Christ.

The only remedy for the bourgeois blather, urbane paganism, and sentimental nationalism that infects too many sermons was Scripture.

In 1935, when the university fell eagerly into the hands of the Nazis, Barth began teaching preaching. (Lectures later published as Homiletics.) Boredom and irrelevance in preaching can only be defeated by strict attentiveness and obedience to the biblical text, he said. The only remedy for the bourgeois blather, urbane paganism, and sentimental nationalism that infects too many sermons was Scripture. The text liberates us from modern theology’s preoccupation – analysis of our human experience of God – so that we can do the main business of the church, daring to listen to and talk about God.

Uniformed Nazis stood at the back of the lecture hall taking notes.

“I didn’t know that Herr Hitler had an interest in preaching,” Barth quipped jovially.

A number of congregants walked out of Barth’s sermon in the university church that spring in which he fiercely asserted the church’s complete freedom to preach what Christ tells the church to preach and utter dependence upon Israel and God’s promises to God’s elected people. Barth sent Hitler a copy of the sermon.

When Barth was kicked out of Germany, his students bid a tearful farewell, asking him for a benediction. Barth famously responded, “Exegesis, exegesis, exegesis.” Our only hope as the world ends? We must preach “Jesus Christ is Lord” as never before.

While Barth may be claiming too much for faithful Bible study and preaching (witnesses like Eberhard Arnold or Dietrich Bonhoeffer would counter “discipleship, discipleship, discipleship”), his commendation of biblical preaching is a needed word in our present moment.

Months before being ousted from his professorship, when asked by his fellow preachers how they should respond to Hitler’s dictatorship, Barth advised them to “preach as if nothing happened.”

This vile mass murderer, a “nothing”? Barth warned that in condemning Hitler, the church must not allow its imagination to be captured by the world’s myths. In our strident (though justly deserved) criticism, he said, we must not give the Nazis inappropriate glory, honor, and dominion that belong only to God. We are in this mess because our witness has become so muddled we can’t tell the difference between Germany and the kingdom of God. Bear witness! Much that we once regarded as something has been rendered into nothing because of the decisive something that has happened in Christ.

Of course, Hitler’s dictatorship is a terrible “something,” but the little man in Berlin is not Lord of history. Thus the Nazi era presents the church with an extraordinary opportunity to testify to the world that the world is God’s and that a Jew from Nazareth who lived briefly, died violently, and rose unexpectedly is even now busy reconciling the world to God. How? In great part through the witness of the church. Nazi power is, like all earthly power, “lordless power” – provisional, passing away, dethroned by the cross and resurrection, though it hasn’t yet gotten the news. All presumptive lordlets are defeated, but not yet fully. The last word will be given not by Hitler, but by Jesus, spoken through frail humans called preachers.

Later, Barth was roundly condemned by the American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr for not forthrightly and frequently condemning Russian communism. Barth replied that communism is an unworkable mistake, a short-lived phenomenon. Besides, many Communist criticisms of American capitalism are on target. American self-righteous exceptionalism may be a greater insult to God’s intentions than Russian communism.

So when he came to America toward the end of his career, Barth made sure to visit American prisons, noting the nasty similarity between democracy’s incarceration and Stalin’s gulags. The American church thinks there’s no difference between an American and a Christian.

Refusing to be jerked around by what the world regarded as momentous, earth-shaking events, Barth said our greatest challenge is to deal with the shock that God has, in Jesus Christ, made our history God’s. How then shall we live now that we know the truth?

What Time Is It?

Though a virus presents a different kind of evil than a genocidal ideology, this pandemic has aspirations to take over our history and name the significance of the present moment in hopes of determining the future. A primary way to resist that viral takeover is preaching.

Palm Sunday, the Episcopal bishop of Washington, D.C., preached at the National Cathedral. She took as her text the “Serenity Prayer,” and urged us to try hard to be serene, even amid Covid-19, to “Change what we can change and to accept what we can’t change and the wisdom to know the difference.” Good advice, eloquently delivered in just the right tone of voice. Yet is it not striking that on Palm Sunday, after reading the long narrative of Jesus’ trial and death, the preacher heard nothing of note? Rather than double-dog-daring us to take up the cross and walk behind a crucified Savior down a way few want to go, the preacher urged us to be serene amid the pandemic, which is what we were doing already.

God has become a Jew from Nazareth who lived briefly, preached what the world didn’t want to hear, died violently, rose unexpectedly, and called us to do the same by joining his revolution.

When the world asks, “Got any word from the Lord?” and we say nothing other than what the world is already telling itself, we impugn the gospel. Maybe the present time is a grand opportunity to tell the story – God has become a Jew from Nazareth who lived briefly, preached what the world didn’t want to hear, died violently, rose unexpectedly, and called us to do the same by joining his revolution. That’s a story the world can’t tell itself.

Before Covid-19, 9/11 was the closest I’ve come to a cataclysmic national disaster. After a three-day drive from a clergy conference in South Dakota, I arrived back home to find my wife, Patsy, in the middle of her weekly Bible study group meeting.

“What book of the Bible are you studying?” I asked.

“Wouldn’t you know it?” said one of the members. “God picked Lamentations for us this week. Good timing!”

Another said, “We’re nobody special. It’s all here. Cities in ruin, towers falling, dust and ash.”

“Nobody in Durham is thinking what we’re thinking, and we wouldn’t have been thinking it without these Jews.”

Christians don’t know what to make of current events, the course of world history, how we ought to live, or the future of the world until Scripture gives us the words truthfully to tell what’s going on. Then preachers narrate our little lives into the pageant of God’s salvation of the world.

April 19, Low Sunday, the sermon preached at the National Cathedral that morning forgot it was the Sunday after Easter, and declared Earth Sunday. Rather than find anything of interest in the resurrection of crucified Jesus, the preacher celebrated the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. That’s the self-help sermon that we educated, upwardly mobile types love to hear.

The lectionary’s assigned gospel was Luke 24, the walk to Emmaus. Later, I watched as a young preacher serving in a little Methodist church in the mountains of North Carolina broadcast his sermon from his kitchen, surrounded by his cloistered family. He lamented having the church absent from one another during this time. He reported on a couple in the congregation who were ill, then led a prayer for those who were working in grocery stores and as healthcare providers. He offered words of praise for a couple of the church members who were working “night and day” in the community food bank, then he read a list of food that was in short supply.

“I bet some of you have prayed that you could make a more impressive witness for Jesus. Well, your prayers have been answered. You get to show what Jesus can do when you just put on your mask and go to work at Seven-Eleven. Drop off anything you can give the food bank at the front door of the parsonage and I’ll see that it gets there.”

He lamented the suffering that many were experiencing. He bared a bit of anger at the inept administration in Washington, specifically condemning the president for refusing to admit his mishandling of the crisis. “Makes you grateful to be a Christian who knows a Lord who forgives, doesn’t it?”

“Still, Donald Trump won’t hear this sermon, so let’s move to more important matters. Christians don’t have to lie or deny because we believe Easter is true,” he said. “What’s the first thing the risen Christ does on Easter evening? Returns to the very people, some of his closest friends, who betrayed and forsook him. Jesus said that he had come ‘to seek out and to save the lost.’ [Luke 19:10] We didn’t know that he meant us until he showed up as we hightailed it out of Jerusalem.”

Then he said, “We’re now on a journey. Jesus’ disciples were on a journey. And one of the frightening things about a journey is that you don’t know where it will end.”

He vividly retold how the “stranger” showed up and joined the two disciples on their walk to Emmaus. “I want everybody to note that they weren’t trying to come to Jesus; Jesus came to them. Jesus showed up before they asked for his presence. I think Luke’s story of this journey says that in whatever direction you’re walking, the risen Christ can show up because he wants to walk with you.”

“Jesus comes to where we are, even when the day seems like it’s getting very dark, and we’re feeling lonely and fearful, and he sits down with us, and feeds us, and our eyes are opened.”

The pastor then described the meal at Emmaus, the breaking and giving of the bread. “We can’t have the Lord’s supper right now, in a time of isolation. But one day our walk through this pandemic will end and we shall be together with the Lord at his table. We will break bread, and give thanks, and be joined together as God’s family. Because that’s the way Jesus does things. He comes to where we are, even when the day seems like it’s getting very dark, and we’re feeling lonely and fearful, and he sits down with us, and feeds us, and our eyes are opened.”

His sermon ended with, “So when you have your supper tonight, with just you and your family, or maybe just you, remember: This pandemic will end but Jesus’ love doesn’t. Jesus will find you wherever you are, join you on your journey, and thereby make you walk in a different direction. Jesus loves to join you at the table. Loving you and wanting to be with you was his idea before it was yours. Let’s pray that God will open our eyes to Christ’s presence during this time.

“Who’s a Christian? Somebody who is going where Jesus takes us, and who, in the middle of the trip, joins him at his table.

“I can’t wait until we all are back together again eating and drinking with Jesus. Amen!”

With Jesus, Scripture, a daring preacher, and some listeners with the guts to not only hear but also join up, this time can be a unique time of God.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Rev. Dr. Kazimierz Bem

Will Willimon is right when he says we should not have every sermon about COVID and points to Barth and his sermons during the years of World War II (July 22). But that example has to be treated with caution. Barth lived and worked in the safety of neutral Switzerland. My grandparents lived in occupied Poland: they saw with their own eyes the destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto in 1943, and then lived through the carnage of the Warsaw Rising in 1944. With all due respect to Rev. Willimon. It is easier to preach about "The Unique time of God" when you are safe and secure and you don't see with your own eyes people taking hands and jumping into flames (Warsaw Ghetto) or dont hear for days sounds of execution rounds and screams of women and children killed in Wola (Warsaw Rising) like my Grandmother did.

Josh Dowdy

Reading this in mid-August, I wonder what Will makes of John MacArthur's refusing to be jerked around by what the world regards as momentous, earth-shaking events.

MICHAEL NACRELLI

American prisons are equivalent to Stalin's gulags? I suspect that Solzhenitsyn would beg to differ!

Susan Prier

Awesome