Subtotal: $

Checkout

The following letters provide a window into the life of Hans Scholl, a young member of the White Rose resistance group in Nazi Germany. This article is an excerpt from Plough’s At the Heart of the White Rose.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Winter–Spring 1942

The “most ridiculous ‘offense’” to which Hans refers in the letter below was described by Mario Krebs: “An incident occurred. A devoutly National Socialist professor of medicine was jeered while lecturing by members of the students’ company. Because the ‘ringleaders’ could not be identified, the entire company was confined to barracks for four weeks – ‘for the most ridiculous offense imaginable,’ as Hans Scholl puts it …After the ‘case’ was forwarded to the judge advocate’s department, the situation became more and more grave.”

To his sister Elisabeth, Munich, February 10, 1942

Dear Elisabeth,

Many thanks for your two nice parcels. Can you really spare that butter and sausage? At present I’m a prisoner of the state again, by which I mean that I am atoning for the most ridiculous “offense” imaginable with four weeks’ confinement to barracks. What makes this unnecessary torment even more galling is that I had so many important plans mapped out in the next few weeks, and for those I definitely needed some quiet evenings in my room. Ça passera. Many more things lie in store, but they won’t divert us by so much as a finger’s breadth from what really matters.

It looks as if we may be able to continue our studies in the summer. That would be a great boon from my point of view.

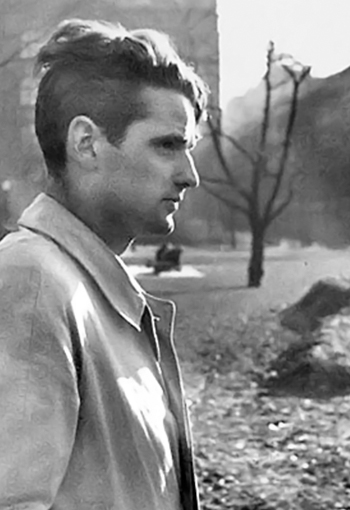

Hans Scholl, 1941

Some friends and I are currently reading Der seidene Schuh [Soulier de Satin] by the French writer Claudel. I regard this work as the greatest event in modern European literature. I wouldn’t dream of comparing Claudel’s language with Goethe’s or Dante’s. That would be as nonsensical as judging baroque art by Gothic standards, but Claudel’s ideas are more profound and comprehensive than Faust’s. You know the book, don’t you?

I recently made the acquaintance of a very distinguished Russian philosopher, Fedor Stepun, who last held a chair at Breslau University. A philosopher of history, he’s one of those people who are so far above the age in which I myself moil and toil that he says the preservation of fundamentals is all that matters – and preserved they will be. He’s right.

You’ll be able to read something about our Christmas vacation at the Coburg skiing lodge in the next Windlicht. Inge wrote it, and a good job she made of it.

I’m expecting Inge here next Saturday. What a great day that’ll be!

I’ll sign off for now.

Fondest love,

Hans

To his parents and his sister Inge, Munich, February 12, 1942

Dear Parents, dear Inge,

It was a big surprise today, on spending a few hours in my room for the first time in ages, to find two parcels there full of delicious things. I gorged myself and then went to sleep. The last few weeks have been physically taxing, and for no good reason.

The situation is becoming more and more tense. The judge advocate’s office has reported our company to the OKW for mutiny. Informers of the most loathsome kind are sprouting in our ranks. I find this incomprehensible, which may be why I’m feeling so depressed. I have no personal connection with the affair. Everyone was interrogated separately today. One of my best friends is among the accused.

I hadn’t expected the majority to react as they have to the least little threat, but I’ve learned a lot.

We’re all delighted that Inge is coming on Sunday. Let’s hope my time isn’t preempted by the army, as it was last Sunday.

How are you, Mother?

All my love,

Hans

After completing the winter semester 1941–1942 and working at St. Ottilien, Hans Scholl took on another internship, this time with the surgical unit of a base hospital at Schrobenhausen, a small town some forty miles northwest of Munich. The hospital was staffed by nuns belonging to the Orden der Englischen Fräulein (Congregation of Jesus).

In the following letter Hans mentions the Gestapo: he took it for granted that the family’s mail was being monitored because the Gestapo, acting on an informer’s tip, had questioned Robert Scholl in February 1942 and threatened him with legal proceedings. The “west wind, with its renewed threat of cloud” is a coded reference to the expectation that Allied troops would soon be landing on the Atlantic coast.

To his parents and his sister Inge, Schrobenhausen, March 18, 1942

Dear Parents, dear Inge,

I don’t know if you received my last letter, because Mother’s made no mention of it. The mail I get here is very irregular. I really sympathize with the Gestapo, having to decipher all those different handwritings, some of which are highly illegible, but that’s what they’re paid to do, and duty is duty, gentlemen, isn’t it!

I’ve nothing to complain of here. There’s plenty of work for me to do. Another batch [of casualties], including many cases of frostbite, arrived here yesterday from Russia, and there’s only one doctor here apart from me. I get on tremendously well with the nurses and the Englische Fräulein. Our joint efforts on behalf of the wounded almost make us forget our own little cares and concerns. The demands on us differ from those involved in opening other people’s letters and prying around in them. I wonder if those gentlemen would be as courageous if they had to slit open dressings sodden with pus and stinking to high heaven? It might upset them, I fear.

How eagerly we longed for the warm March days, and now they’re here! We sun ourselves on the terrace at lunchtime. We inhale the scent of spring in spite of everything. In spite of the west wind, with its renewed threat of cloud. In spite of the smell of hospital and army boots. In spite of my long hair, which for some incomprehensible reason strikes certain of my fellow men as too long, and on whose account I should really be at the barber’s instead of relaxing here.

I regret that nearly half my time here is up, and that I’ll then have to move back to Munich. I’m looking forward to Munich too, though. If only I could come home sometime soon.

Fondest love,

Hans

To his parents, Schrobenhausen, March 29, 1942

Dear Parents,

Many thanks for the letters and the laundry. My quietest days here are over. Tomorrow another batch of badly wounded men arrives from Russia. I’ll have plenty of work to do in my last two weeks.

Last Sunday, when I had to deputize for the senior medical officer, it became necessary for the first time (discounting the French campaign) for me to perform a vital operation during the night. It went well.

You wouldn’t believe how kind these nuns are. They read your every thought. They’re like that because they draw on another source of strength, one that never fails.

Not to mention the spring.

Best regards to everyone including the uninvited readers of this letter, especially Traute.

Yours ever,

Hans

P.S. These are the kind of little treats the “English” [nuns] slip me. (This sentence is quite innocent.) There are 7 (seven) in all. I mention this purely for the record.

To Rose Nägele, Munich, April 13, 1942

Dear Rose,

I’ve simply got to write to you at last. I’ve kept you waiting an awful long time. You’ve waited for many a melancholy hour, I know, but it couldn’t be helped. I doubt if I’ll ever be able to love anyone happily and contentedly. There’s far too much afoot for me to keep a promise at this stage and say that my course is set for good and all.

I’d much rather have paid you a visit at Easter, instead of writing in this nebulous vein, but I couldn’t get away. I didn’t even get Easter off. I was satisfied with my internship, for all that. My four weeks in a medium-sized town in Upper Bavaria, rural and outwardly superficial, brought me much joy and a little, albeit genuine, sorrow. I breathed good air there and chatted with hospitable people. Now I’m back in Munich. The time of year is making me restless and rousing many a demon, contrary to my intentions. My most faithful friend is still Carl Muth. I’m to be found at his home every day.…

Best regards,

Hans

To his mother, Munich, May 4, 1942

Dear Mother,

The words of that fervent seeker after God, St. Augustine, will convey more to you on your birthday [May 5] than mine ever could. That’s why I’m putting them first of all, because I know that no one is closer to them than you. However great the turmoil prevailing today – so great that one often has no idea where to turn because of the multitude of things and happenings around me – elemental words of that kind loom up like beacons in a stormy sea. That’s my conception of poverty, that one should fearlessly jettison old ballast at such moments and powerfully, freely, head for the One. But how rare such moments are, and how often and repeatedly man subsides into drab uncertainty, into the stream that flows in no direction, and demons are always busy grabbing him by the hair at every opportunity and dragging him down.

Sophie has arrived here safe and sound. She’ll be staying at Professor Muth’s for a few days until the room’s ready. She’s well off there. Is Liesel coming next Sunday? Please write and tell me soon, so I can make arrangements.

Fondest love and best wishes on your birthday,

Hans and Sophie

From At the Heart of the White Rose: Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.