Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Three Open Wounds

-

Why I Love to Wear a Head Covering

-

Vincent van Gogh

-

All Things in Common?

-

The Sacrament of the Last Supper

-

Readers Respond Summer 2016

-

Serving Children in Pyongyang

-

Blessing out of Pain

-

Life Together: Beyond Sunday Religion and Social Activism

-

Solidarity

-

Possessions

-

Differences

-

Let Yourself Be Eaten

-

Repentance

-

At Table

-

Poem: Rainfall

-

From Property to Community

-

Why Community Is Dangerous

-

Confessing to One Another

-

The Way: Two Millennia of Christian Community

-

Friars of Manhattan

-

American Hospitality: Jubilee Partners

-

Live Like You Give a Damn

-

The Luxury of Being Surprised

-

The Incident in Changu’s Pepper Patch

-

Two Poems

-

Editors’ Picks Issue 9

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

This article was originally published on June 1, 2016.

On November 24, 1755, ten Moravian missionaries and a child were murdered at Gnadenhütten, Pennsylvania, near modern-day Lehighton, on Mahoning Creek. Susanne Luise Partsch, who had recently come to Gnadenhütten with her husband George, saw men “running from one house to another with firebrands to set them alight.”footnote A Native American war party burned the church, school, bakery, and dwellings to the ground, and burned several residents, including an infant, alive in their homes. The cattle were slaughtered, while stores, tools, and supplies were taken or ruined. One woman whose husband was killed in the raid was seized; while in captivity, she was raped and abused so severely that she never fully recovered. Susanne Partsch survived by leaping from a second-story window, fleeing, and taking shelter under a hollow tree. A local militia member found her the next morning and returned her to the settlement. She wrote of her experience, “I fainted at the sight of the charred bodies, and they had trouble bringing me back to my senses.”footnote

The massacre of the mainly German missionaries was a minor event in a much larger conflict between France and England called the Seven Years’ War. The North American theater of this conflict was known as the French and Indian War, during which American colonists fought alongside British troops and their Native American allies against the French and their Native American allies. Native American tribes were forced to decide between fighting for the British or resisting them. For some Native Americans, most notably the Delaware chief Teedyuscung, the war presented an opportunity to reclaim ancestral lands the British had stolen. Teedyuscung had converted to Christianity before the war and lived with the Moravians at Gnadenhütten for some time, but when the Delaware were attacked by other tribes, the Moravians urged them not to resist, which offended Teedyuscung. He rejected Moravian pacifism and began raiding white and Native American settlements.

Only twelve days before the massacre, on November 12, the Moravians had decided, despite signs of impending violence, that it was “better that a Brother should die at his post than withdraw and have a single soul thus suffer loss.”footnote The Moravian missionary John Martin Mack, who had devoted his life to ministering to native peoples, had encouraged the missionaries at Gnadenhütten (“houses of grace”) to remain at their post. (On hearing the news of the slaughter, he was heartbroken, yet still joined other Moravians in urging their friends among the Delaware not to seek revenge on their behalf.)

Printed with permission of Moravian Archives, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Aftermath

The day after the assault, the Moravian congregation in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, was summoned at dawn for daily prayer with the ringing of the church bell. Bishop August Gottlieb Spangenberg read the Bible verse designated for the day from Genesis 42: “Joseph made himself strange unto them and spake roughly unto them.” The bishop told the congregation that sometimes God speaks roughly and seems strange, “but we know his heart.” With a quavering voice, he informed the congregation of the martyrdom of their brothers and sisters at Gnadenhütten, twenty-five miles to the northwest. The congregation prayed and wept. Soon Native American and white refugees from the Blue Mountains, including George and Susanne Partsch, began arriving in Bethlehem, seeking food, shelter, and protection. Susanne felt “wretched and had to bear a serious illness.”

In all, about eight hundred people made their way to Bethlehem and nearby Nazareth, a rare instance of Europeans and Native Americans in the eighteenth century seeking shelter together. Moravian historian Joseph Mortimer Levering notes that the presence of seventy Native American refugees from Gnadenhütten “put a strain upon the confidence and good will of some of the Bethlehem people, under the poignant grief they felt for the awful fate that had befallen their brethren and sisters on the Mahoning; all on account of Indians and at the hands of Indians; and under the growing dread of an attack upon Bethlehem.”footnote Despite their anxiety, Bishop Spangenberg urged the Brethren not to close their hearts to the refugees, who had been driven from their homes by violence, and so the Moravians, sometimes reluctantly, continued to protect the Native Americans from whites intent on revenge.

To relieve overcrowding in the Bethlehem commune, the Moravians helped the Native Americans build a village called Nain a mile from town, where they could live according to their traditional economy while still worshiping as Moravians. It took a while to find a suitable spot and clear the land for building, but finally, in October 1758, the village chapel was dedicated. Some non-Moravian whites took issue with Nain, and Teedyuscung, who objected to the idea of Delawares embracing the church’s pacifism, tried in vain to persuade Native Americans to leave. In 1763, the Pennsylvania Assembly insisted that the Moravians bring their Native American Brethren to Philadelphia in an attempt to protect them from the so-called Paxton Boys, a group of vigilantes responsible for murdering Native Americans. Conditions in the Philadelphia refugee camp were grim, and eventually the Moravian missionary David Zeisberger was allowed to take a group out of Pennsylvania to settle in Ohio.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Moravian Roots

To understand the Moravian commitment to pacifism during the French and Indian War, it is important to understand the church’s history. Founded in the mid-fifteenth century as the first peace church, the Moravian Church – called the Unitas Fratrum (“Unity of the Brethren”) – at one time had some four hundred congregations in Bohemia, Moravia, and Poland. The church was virtually destroyed by religious persecution in the Holy Roman Empire during and after the Thirty Years’ War, but a remnant survived. The last bishop of the Moravian branch of the Unitas Fratrum was Jan Amos Comenius, who, while most famous for his writings on pedagogy and child rearing, also was one of the foremost pacifist authors of the early modern period. In 1722, a group of Protestants fled persecution in Moravia and were granted refuge on the estate of Count Nikolaus von Zinzendorf.

The Moravians built a village called Herrnhut on Zinzendorf’s land, and with his assistance it became a unique Christian community. Everyone who agreed to live according to the Brotherly Agreement, ratified in 1727, was welcomed regardless of church affiliation or nationality. The Brotherly Agreement stipulated that the only reason to live in Herrnhut was service to Christ. The Herrnhuters called one another “brother” and “sister,” and they adopted rituals and offices modeled on the example of the earliest Christians. The rituals included foot washing, the kiss of peace, and the agape meal. Though they called themselves the Brüdergemeine (“Community of the Brethren”), women as well as men were chosen as the leaders of the community.

On August 13, 1727, the Herrnhuters experienced a significant spiritual transformation that inspired them to embark on an extraordinary fifty-year global mission. The first missionary, Leonard Dober, traveled to the island of St. Thomas in the West Indies in 1732. He hoped to befriend those suffering the cruelty and indignity of slavery. In 1735, the first Moravian missionaries arrived in North America and befriended Native Americans near Savannah, Georgia. (It was while he was on route to Georgia that John Wesley, the cofounder of Methodism, first encountered the Moravians.)footnote In 1740, Moravians arrived in Pennsylvania, and the next year they began the community of Bethlehem, which was to be a base of operations for an extensive network of missionaries. Dozens of Moravians learned Native American languages, and some were adopted into various tribes in the Iroquois Confederacy. Moravian men and women lived with Native Americans in villages like Shamokin, Shekomeko, and Friedenshütten.

Moravian Single Brothers’ House, built 1769

Moravian Single Brothers’ House, built 1769

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

The Ohio Massacre

Bethlehem was not only the economic and administrative headquarters for the Moravian mission in North America – it was intended to be a “city on the hill.” The Brethren in Bethlehem built some of the largest buildings in colonial Pennsylvania to house the hundreds of men, women, and children who lived there under the Brotherly Agreement. Some residents agreed to stay permanently to raise crops and provide support for the church, while others were “pilgrims” who agreed to go where they were sent. Many of these pilgrims worked with Native Americans, especially among the Lenape, or Delaware, people. Though the influx of war refugees in the late 1750s severely strained Bethlehem’s economy and social structures, the church survived. Brethren were not permitted to join the militia or serve in the army, but the church’s rules did allow for self-defense and the defense of women and children. They explained to outsiders that they were neither kriegerisch (willing to serve in the military) nor quäkerisch (absolutely nonviolent); instead, they were willing to take up arms only if necessary to preserve the lives of the innocent and defenseless.footnote

On several occasions in the 1750s and 1760s, the Brethren in Bethlehem were threatened by Native American war parties and white mobs. Many colonists accused the Moravians of plotting with Native Americans and even arming them, but in fact Moravians consistently sought to be people of peace. In order to protect the town from the type of assault suffered at Gnadenhütten, the Moravians built a stockade around Bethlehem and the neighboring community of Nazareth. Brethren kept watch day and night, with orders to fire warning shots if anyone was seen moving against the town. In a move that shocked some non-Moravian white settlers, armed Native American Brethren stood watch with white Brethren. In this way at least one raid was prevented. On Christmas Day in 1755, Bethlehem’s Moravians celebrated the birth of Christ as they usually did, by playing trombones just before dawn. According to later reports, the sound of brass instruments, often associated with armies, so alarmed a group planning a dawn assault that they aborted their mission and retreated into the woods.

In 1775, war again engulfed the British colonies in America. The Single Brothers’ House in Bethlehem became a hospital for wounded soldiers from both sides, and Moravians strove to bury the war dead with dignity. Though the British Parliament had granted Moravians an exemption from military service in 1749 in recognition of their long-established pacifism, during the American Revolution Moravians often had to pay large indemnities to avoid conscription. On several occasions, both sides threatened the Moravians with forced conscription. Some Brethren were jailed; others fled.

At the site in Ohio where David Zeisberger and his wife Suzanna had brought their congregation of Lenape and Mohican Brethren from Pennsylvania, a Mohican named Joshua was now the head of the new community, named Gnadenhütten in honor of the martyrs of 1755. By the start of the Revolutionary War, the village had grown to over two hundred people, all Native American. As the conflict moved westward, the British forcibly relocated the Moravians to Sandusky in 1781. Many starved, died of disease, or froze to death during the winter. In the spring, over a hundred Brethren were allowed to return to their villages on the Tuscarawas River where they hoped to plant crops and hunt game.

Moravian pottery

Moravian pottery

Get the Book

Get the Book

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

But the specter of war and hatred stalked the land. After several non-Moravian white families were massacred by Native American war parties allied with the British, an American militia of about 160 people led by David Williamson set out for revenge. Rather than seeking out the guilty, they decided to attack the innocent pacifists at Gnadenhütten. In early March 1782, they occupied Gnadenhütten and rounded up other Native Americans from surrounding villages and woods. On March 7 they held a mock tribunal, convicted the Moravian Brethren of murder, and sentenced them to death. The only mercy they showed was to honor the request of the Moravians to prepare themselves for martyrdom. Throughout the night the Native American Brethren confessed their sins, comforted one another, and sang hymns to Christ their Savior. The next day, the white militia murdered ninety-six people. Two boys who managed to hide under bodies bore witness to the atrocity and the courage of the martyrs. According to their report, there were two “killing houses,” one for men and one for women. Most were killed by mallets and tomahawks, and militia members scalped many of those killed, some while they were still alive. Nearly half of the victims were children. According to one participant: “Nathan Rollins had tomahawked nineteen of the poor Moravians, & after it was over he sat down & cried, & said it was no satisfaction for the loss of his father & uncle after all.”footnote

After the killing spree was over, the militia looted the town and burned the buildings with the bodies in them. Later, Moravian missionary John Heckewelder visited the site and buried the remains of the martyrs. None of the militia members who participated in the massacre were ever brought to justice, though some were killed by non-Moravian Lenape out of revenge. British authorities granted Zeisberger permission to take the remaining members of his Lenape and Mohican congregation to Canada where they would be safer. Ontario’s Moraviantown traces its origins to these refugees from Ohio.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

American Martyrs

Sadly, the 1782 Gnadenhütten massacre virtually ended the fifty-year Moravian effort to bring Europeans and Native Americans together in Christian community as brothers and sisters. As news of the events there spread from tribe to tribe, Native Americans became less and less trustful of white people. Two decades later, the Shawnee chief Tecumseh reminded the future US president William Henry Harrison: “You recall the time when the Jesus Indians of the Delawares lived near the Americans, and had confidence in their promises of friendship, and thought they were secure, yet the Americans murdered all the men, women, and children, even as they prayed to Jesus?”footnote

Today, little remains of the courageous Moravian outreach to the First Peoples of North America, but several monuments to their efforts still stand. The most important of these historical markers are found near the Wyoming Valley in Pennsylvania and near the Tuscarawas River in Ohio. Both were erected by Moravians to honor those who lost their lives in the two settlements that shared a name – Gnadenhütten. In Pennsylvania, white Moravians were killed by Native Americans. In Ohio, their Native American brethren were killed by white Americans. In both cases, the martyrs were men, women, and children who tried to follow the way of Christ in a violent and dangerous time, looking past differences in skin color, language, and customs to call one another brothers and sisters. They were prepared to sacrifice their own lives rather than take the lives of others. We can view those who died in these two communities as victims or victors. For their brothers and sisters in the faith, those Moravians joined the ranks of thousands of Christian martyrs who bore witness in life and death to their faith in Christ by loving their enemies and praying for those who persecuted them.

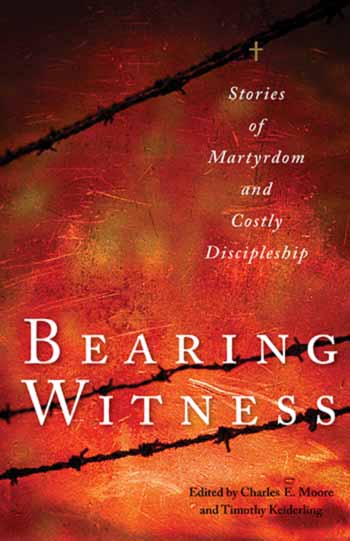

From Bearing Witness: Stories of Martyrdom and Costly Discipleship.

Mass grave at the site of the 1782 massacre, Gnadenhütten, Ohio

Mass grave at the site of the 1782 massacre, Gnadenhütten, Ohio

Footnotes

- Memoir of Susanne Luise Partsch, in Katherine Faull, ed. Moravian Women’s Memoirs: Their Related Lives, 1750–1820 (Syracuse University Press, 1997), 111–113.

- Ibid.

- Quoted in J. T. Hamilton and Kenneth G. Hamilton, History of the Moravian Church (Bethlehem, 1967), 142.

- Joseph Mortimer Levering, A History of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania 1741–1892 (Bethlehem: Times Publishing Company, 1903), 315.

- Geordan Hammond, John Wesley in America: Restoring Primitive Christianity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014); Colin Podmore, The Moravian Church in England, 1728–1760 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998).

- Jared Burkholder, “Neither ‘Kriegerisch’ nor ‘Quäkerisch’: Moravians and the Question of Violence in Eighteenth-Century Pennsylvania,” Journal of Moravian History 12 (2012): 143–169.

- J. T. Holmes, The American Family of Rev. Obadiah Holmes (Columbus, Ohio: 1915).

- Quoted in Major Problems in American History vol. 1, ed. Elizabeth Cobb et al. (Cengage, 2011), 205.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Rowland F. Stenrud

I was an absolute Christian pacifist for a time. But I was never a political pacifist meaning that I never expected the godless world to embrace non-violence. That would be like asking a tiger to become a vegetarian. Nevertheless, Christians should never kill on behalf of the State. I guess that is a political statement as well as a moral one. On the other hand the only people that Jesus commanded us to love more than we love ourselves are other Christians. Jesus did not ask Christians to value the lives of non-Christians more than their own. Jesus gave this new commandment to his followers, a commandment that superseded the commandment to love our neighbor as we love ourselves in connection with fellow Christians: “A new commandment I give you, that you love one another just as I have loved you, you also are to love one another. By this all people will will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another” (John 13:34). The Christians of Europe did not have to be pacifists in order to obey Jesus’s new commandment during WWI and WWII. All they had to do was to refuse to kill fellow Christians, and that would have prevented much of the bloodshed of those wars. The worst sin of the Christian community has been their willingness to kill other Christians over doctrinal differences or because these other Christians were citizens of a state that may have been hostile to their state. But Christians shouldn’t kill anyone on behalf of the state. However. Jesus never condemned engaging in violence in defense of oneself, one’s family or one’s neighbors. If a Christian loves his fellow Christians as Jesus loves them they should be willing to defend them from being killed by unjust murderous gangs of armed men. The obligation to defend innocent Christian life overrules the Christian dedication to non-violence. These Moravians should never have migrated to a dangerous and violent area without being prepared to defend themselves. By making themselves totally vulnerable to the violence of others they were putting God to the test. It would be as though they eschewed all medical care in the belief that if God did not want them to be sick, God would heal them. Did they not think of how much pain they caused the Father by refusing to protect themselves from the violence of others? They put God in the position of having to directly intervene in the affairs of men in order to save those he especially loved. It seems to me that these saintly Moravians put God to the test: If you love us you won’t let us die even though we are doing nothing to defend ourselves. Jesus was tempted to test God’s willingness to directly intervene to save his life. Such a direct intervention by the Father would prove his claim to be the Son of God to the unbelievers. The devil took Jesus to the top of the Temple in Jerusalem and said to him, “If you are the Son of God, throw yourself down from here, for it is written 'He will command his angels concerning you, to guard you,'” and “on their hands they will bear you up, lest you strike your foot against a stone’” (Luke 4:11 quoting Psalm 91:11-12) And Jesus answered him, “It is said, ‘You shall not put the Lord your God to the test.’” (Luke 4:12; and see Deut. 6:16 and Exodus 17:1-7). Love of our fellow man especially of our fellow Christians must be our guide and not some moral principle of non-violence. If I were some murderous thug, I cannot see how I would be helped if some Christian allowed me to murder his family rather than taking up a weapon and killing me. But, I have a belief that in a sense allows me to kill on behalf of my fellow Christian without feeling that I have damned someone to hell. I believe that, when the murderous thug is resurrected, that is the Father’s first step in saving him from himself. Both the Judgment and the baptism in the Lake of Fire are God’s instruments of saving the wicked, of saving unbelievers. If I were this murderous thug killed by a Christian, who was saving the lives of his family and friends, I would be among the multitude that cannot be numbered in Revelation 7:9-17. It is in the afterlife that Jesus will be the shepherd of this murderous thug. He was obviously not his shepherd during his earthly life. The 144,000 is a symbolic number referring to those saved on this side of the grave. These are the Jews and Gentiles who were filled with the Spirit of Jesus on this side of the grave. This earthly Christian community is the Israel of God. But, in the end, God will save everyone from their sinful selves. God the Father will make everyone a new person, a new creation in Christ. God’s saving work is a creation work in which he makes us in the image of the New Adam, Jesus of Nazareth.

Debra Winchell

Thank you very much for writing this and answering some of my questions. I have a Quaker ancestor who became a Moravian, Jethro Ashley; a Native relative killed at Gnadenhutten, Joseph Shabash; and a Native American ancestor from Ohio who was United Brethren whom I haven't found much on, Solomon Hise. Too many people conveniently believe someone else in assigning him European parents. I believe he was the descendant of a German man named George Heiss who was captured and held by the Shawnee for two years during the American Revolution, but doubt I can prove it.