Subtotal: $

Checkout-

The New Malthusians

-

The Spiritual Roots of Climate Crisis

-

Tradition and Disruption

-

The Apocalyptic Visions of Wassily Kandinsky

-

War and the Church in Ukraine: Part 1

-

The Griefs of Childhood

-

Everything Will Not Be OK

-

Jesus and the Future of the Earth

-

The Other Side of Revelation

-

American Apocalypse

-

Syria’s Seed Planters

-

At the End of the Ages Is a Song

-

Searching for Safety

-

Stable Condition

-

Editors’ Picks: In the Margins

-

Editors’ Picks: The Genesis of Gender

-

Editors’ Picks: Sea of Tranquility

-

Poem: “Stopping By with Flowers”

-

Poem: “Sugarcane Memories”

-

Poem: “Sonnet Addressed to George Oppen, Arlington National Cemetery”

-

Diaconía Paraguay

-

Winners of the Second Annual Rhina Espaillat Poetry Award

-

Letters from Readers

-

Charles de Foucauld

-

Covering the Cover: Hope in Apocalypse

-

War Is Worse Than Almost Anything

-

The Last Battle, Revisited

-

The Problem with Nuclear Deterrence

-

A Haven of Olives

-

Book Tour: Time for an Intervention

-

Hoping for Doomsday

-

Radical Hope

The Sermon of the Wolf

The Anglo-Saxon world was collapsing amid Viking terror and political chaos. One bishop held a kingdom together.

By Eleanor Parker

July 29, 2022

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

“Beloved ones, know what is true: this world is in haste, and it is nearing the end.”

—Wulfstan, archbishop of York, AD 1014

These apocalyptic sentiments could have appeared yesterday on the front page of the New York Times, or two thousand years ago in an epistle to the early church. In fact, they were written just over one thousand years ago, by an Anglo-Saxon bishop. They are the opening of a sermon preached by Wulfstan, archbishop of York, in AD 1014. He begins by warning his hearers that the state of the world is getting worse, and that this can mean only one thing: “In this world the longer things go on, the worse they are, and so it has to be that things grow very much worse because of people’s sins, before the coming of Antichrist, and then indeed it will be grim and terrible throughout the world.”

Like many medieval Christians, Wulfstan believed that the end of the world was a prospect with which all thinking people ought to reckon seriously. It seemed only wise: Christ warned his disciples to read the signs of the times, to recognize “wars and rumors of wars,” upheavals in the natural world, and the prevalence of sin and violence as indications that the apocalypse would soon be at hand. The end of the first millennium, too, seemed to accelerate the prospect of the apocalypse to Wulfstan’s contemporaries, and those who can remember the year 2000 will be well aware how significant dates like the turn of a millennium can produce disquiet, even in a supposedly rational age.

In 1014, however, Wulfstan had specific reasons for feeling that the end times could not be far away. England was in a dire state. Since the last decades of the tenth century, the Vikings – Anglo-Saxon England’s old enemies – had been conducting campaigns of persistent and devastating raids, ever growing in intensity. The pressure to resist them had drained the country financially, militarily, psychologically, emotionally. King Æthelred and his advisers tried various strategies to combat the danger, but the scale of the challenge was tearing them apart; the court had descended into factionalism, and the king himself was increasingly blamed for all that was going wrong. There’s a reason that Æthelred has become known to generations of schoolchildren as “Æthelred the Unready,” a play on words which implies not lack of preparation (though he could be accused of that) but the idea that the king was badly counseled or ill-advised. By 1014, England was facing not just piracy and internal disputes but the real threat of invasion. At the end of 1013, Æthelred had been forced to flee England and the country had fallen under the full command of the Danes. Barely a month later, the sudden death of the Danish king Sweyn unexpectedly turned things upside down again, and Æthelred was able to come back. However, Æthelred was only invited back by his advisers, according to a contemporary source, on the condition that “he would govern more justly than he had done before” – a phrase which seems to suggest little faith that he would do so.

In his apocalyptic sermon, Wulfstan speaks to a country in total moral collapse. “Nothing has prospered now for a long time, at home or abroad,” he says, listing “harrying and hunger, burning and bloodshed,” plague, pillaging, and unfair taxation among the many evils afflicting the nation. But it isn’t a warmongering sermon; in fact, Wulfstan says very little about the enemy. He’s much more concerned with the idea that under sustained and unrelenting pressure, the English people have abandoned their obligations to family, community, and country. “The devil has now led this nation too much astray for many years, and there has been little loyalty among men, though they spoke well, and too many injustices have reigned in the land,” he tells his hearers bluntly. “Daily one evil has been piled upon another and injustices and many violations of law committed all too widely throughout this entire nation.”

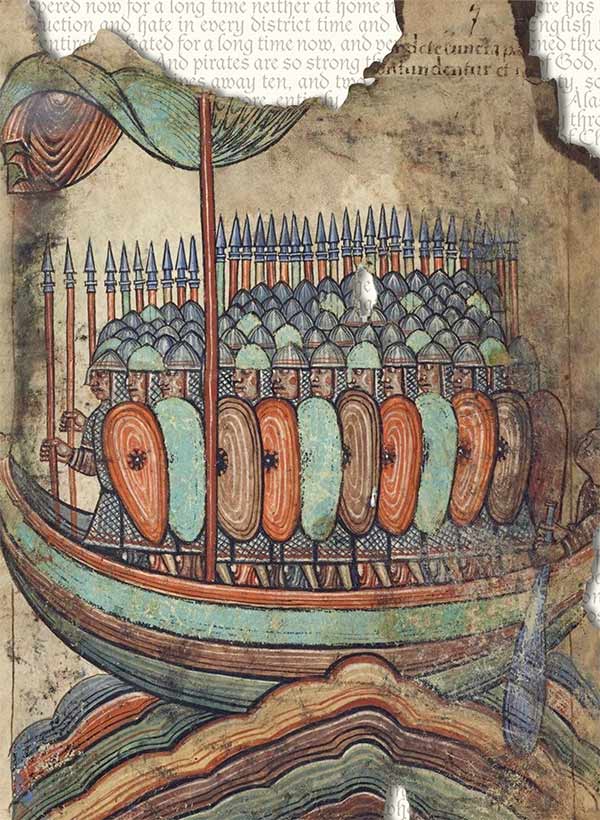

Viking attack, from a Saint-Aubin manuscript, ca. 1100

Wulfstan goes on to detail all the different ways in which the essential bonds holding society together had begun to break down. He gives specific examples, described in a manner intended to horrify and disgust his audience. His account still has the power to shock a thousand years later: particularly horrible are his descriptions of desperate people selling their own family members into slavery and his fierce denunciation of the sexual abuse of female slaves. There is no fudging of the details, no opportunity for the audience to turn their eyes away; in stark and brutal language, Wulfstan makes his audience confront exactly what their society has become. No wonder he thought the coming of the Antichrist could not be far away.

This sermon is known as the “Sermo Lupi,” the “Sermon of the Wolf.” The title plays on Wulfstan’s own name, but it is also an apt characterization of the angry tone of his urgent message. In Anglo-Saxon culture, the wolf was the ultimate outsider: the archetypal outlaw, a dweller in the wilderness and on the borderlands. This title suggests that Wulfstan, at least on this occasion, embraced the wolf as a facet of his identity: it is not gentle preaching but the howl of a wild beast, coming out of the darkness. It’s meant to frighten you, to send a shiver down your spine.

But Wulfstan was no prophetic voice crying in the wilderness; he spoke from the heart of power and influence. He was an active and experienced politician who had served first as bishop of London, then as bishop of Worcester and archbishop of York, making him the country’s second most senior church leader by 1014. He was an adviser to King Æthelred and had been involved in contemporary debates about how to respond to the threat of the Vikings – whether by fighting them, paying them off, or trying to convert them, all strategies used at different moments, with different levels of success. In these times, though, power was no guarantee of personal safety. In 1012 Wulfstan’s senior colleague, the head of the English church, Ælfheah, archbishop of Canterbury, had been murdered by a Viking army. Whether the end of the world was coming or not, Wulfstan might have felt there was a good chance his own end wasn’t far away. Death had become a daily reality.

We can only guess what personal fears and griefs lay behind the howl of anger in his sermon. But – wolf though he was – Wulfstan was also the very opposite of an outlaw; he was a maker and writer of laws, who had worked on the formation of Æthelred’s legal codes. Law was central to his thinking, and it’s at the core of his sermon. Many of the terrible sins Wulfstan describes are diagnosed by him as breaches of law, a concept which for him had the broadest possible meaning: it involved not only actual crime, but violations of personal integrity, such as breaking your word, neglecting your duty to your parents, or disregarding your marriage vows. It also covered the breach of religious obligations like fasting and the mistreatment of church property.

We wouldn’t think of all these as questions of law today, but for Wulfstan they were all part of the same thing: God’s laws, the laws by which society governed itself, and each individual’s moral commitment to his or her obligations should all be connected. They involve the important value of what he calls getreowþ, an Old English word related to our word “truth,” which encompasses loyalty, honesty, trustworthiness, and integrity.

Figurehead on replica Viking ship outside the Vancouver Maritime Museum

As he saw it, all these were in jeopardy in 1014. However, for Wulfstan diagnosing his society’s ills as breaches of law was not a source of despair, but an opportunity. It meant he could offer a plan of action. In this sermon his purpose is not just to denounce and lament, to criticize without providing solutions. His aim is to preach repentance and amendment – to convince people that things can get better, even in the shadow of the end times. The end will come; he has no doubt of that, and right now things are almost as bad as they can be. But there are measures we can take in the meantime, he suggests, things that will help. They won’t stave off the apocalypse or keep the Antichrist away. Yet they’re still worth doing – both morally right in themselves and a remedy for present evils.

His message is simple: repent, repair, do better. There’s no pretense that it’ll be easy. “A great wound needs a great remedy,” he says, “and a great fire needs a great amount of water if the blaze is to be quenched.” The worse the situation, the more work and collective effort it will take to mend it. But the promise that it can be mended is, nonetheless, a remarkably hopeful takeaway from such a fierce and angry sermon. As a response to the threat of coming apocalypse, it’s almost optimistic. Wulfstan asserts a firm belief that doing what is right doesn’t cease to matter, even if time is running out. In fact, it matters more. Living in the shadow of the end of the world doesn’t involve giving up on life, but recommitting yourself to what is most precious about it. For Wulfstan, that means especially strengthening the bonds we share with other people – our families and communities, the vulnerable and the poor, those we trust, and those who need to be able to trust us.

Though directly confronting the problems of his own time, Wulfstan’s sermon speaks powerfully to our time as well. His picture of a society suffering from a breakdown of “truth,” in which both institutions and individuals have succumbed to corruption and self-interest, is uncomfortably familiar. So too is his warning that in the face of sustained crisis, a society can lose sight of what it values and believes to be true; fear and despair can make people do terrible things, sacrificing even what they hold most dear.

There is an emotional resonance in Wulfstan’s opening statement that the world is “in haste,” advancing towards its end at a frightening speed. Today, people often talk about feeling that the pace of life is speeding up, and we tend to attribute it to modern technology and rapid social change. Over the past two years especially, between political crises and pandemic and war, people have joked wryly that 2020–22 has felt like a decade or a century all rolled together. The problem is not really the speed at which things are happening, but the feeling that we can’t keep up with them. We struggle with the disparity between the pace at which events are unfolding around us and our ability to process them, mentally and emotionally – barely finished with one once-in-a-generation crisis, before we’re suddenly plunged into the next. It’s like being caught in a fast-flowing river, swept along by the stream, just trying to keep one’s head above water.

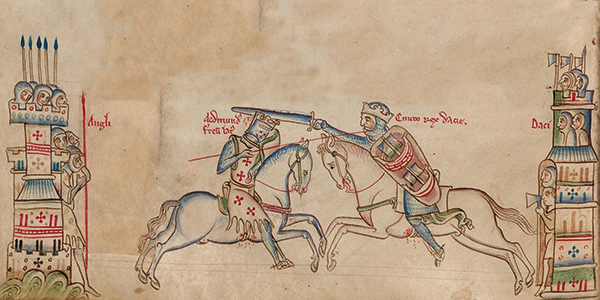

Fourteenth century illumination depicting kings Edmund Ironside and Cnut, from the Chronica Majora

It seems the people of Wulfstan’s time felt the same. In their time and our own, this sense of haste can lead to feelings of helplessness or despair. If things move so fast, and they’re only going in one direction, what’s the point of trying to change what’s happening? But Wulfstan’s conclusion stresses action, the belief that there are still things worth doing and steps that we all can take. “Let us do what we need to do: turn toward the right and abandon wrongdoing, and earnestly atone for what we previously did wrong. And let us love God and follow God’s laws … and have loyalty between us without deceit.”

Wulfstan practiced what he preached. In 1016, after two more years of devastating warfare, the English king was finally defeated and the Vikings were victorious. England was conquered, and the Danish prince Cnut – a young Viking whose actions so far had shown evidence of nothing but brutal cruelty to his enemies – became king. Wulfstan might have thrown up his hands in despair, thinking all his warnings had been in vain. What advice could he offer to a king like this? What hope could he preach now?

But he didn’t give up. He still had work to do. All along, his priority had been the moral health of the nation, and he still believed that the unifying power of law could offer a cure. So Wulfstan became Cnut’s chief English adviser, writer of the king’s laws and public pronouncements, which emphasized the need for conquerors and conquered to live in harmony, to observe the same laws, to share common values, and to find reconciliation after the long years of war. This time, Wulfstan’s work had real success. Cnut proved to be susceptible to influence; peace came, at least for a time, and the laws they made formed the basis for many later codes, ties that still sought to hold English society together centuries after Wulfstan himself was dead.

Perhaps “this world is in haste, and it is nearing the end,” but it always has been. Whether it comes soon or late, the end is always coming. We don’t know what will precipitate the end times; it turned out not to be the Vikings, or the year 1000, but it might yet be nuclear war or climate apocalypse. If we can learn anything from those who lived under the shadow a thousand years ago, it is that there is work worth doing even in the darkest times. Wulfstan found his hope in restoring the bonds of community and family, faith and justice – bonds forged not only by rulers and social reformers but by individuals and their choices, however small each of these may seem. Whatever the darkness of the times we live in, some good can yet be done by every turn toward the truth.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Kay Perry

“A great wound needs a great remedy”. I love the plainness and directness of this. And it is endlessly applicable.

Greg

Ramblings: A return to the truth in times of hopelessness. Truth is all we have. It is the ground on which we stand. It is the Way to Life. The Way of Truth leads to life. Jesus said I am the Way the Truth and the Life. The early Christians called themselves people of the Way. The Way of what? The Way of Truth. Jesus was the Truth incarnate as a man. God/Truth come as a man to teach us the Way. The Way of Truth. Truth is God, the ground of our very being.

Edward Falzone

there is always light at the end of the tunnel, It is God

Bob Taylor

I'm eager to read your books. I hope he preached Christ crucified. Perhaps you stated in the article that he did, but if so, I missed it. Of course, the moral law must be preached, but its purpose is not to rouse people to moral improvement, but to drive them to despair of themselves before God, who is perfect. Then, they may be receptive to the glorious Gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ.

Susan Hill

Excellent writing! What a motivational spurring! Wow!