Subtotal: $

Checkout

What Willie Nelson Can Teach Us about Revival

A revival of anything often looks disturbingly different or doomed to irrelevance but really is a reconnection to roots so old they now seem new.

By Russell Moore

October 13, 2023

Willie Nelson was a door-to-door Bible salesman, but that didn’t work out. Then he tried to find his way as a country music singer but that didn’t work out either. He tried for years to fit the image and sound of what Music Row executives, and national radio audiences, expected from country music, until he gave up on pleasing Nashville and moved back to Texas. One friend said: “You get the impression that when he was living in Nashville he was sending out his songs like a stranded man sends out messages in bottles, and that when he moved to Austin, he suddenly discovered that all those bottles had floated to shore among friends.” As historians of the era described it, “Back in his native Texas, Nelson started over – and revived his career.” At the same time, a similar revival was happening in the lives of some other singer-songwriters, in what came to be known as “outlaw country.”

Outlaw country was so named not because it deals lyrically with bandits and thieves (although, naturally, it sometimes does) but because it started well outside of the cultural norms of the Nashville establishment. As one observer put it, “They resisted the music industry’s unwritten rules, which prescribed the length, the meter, and the lyrical content of the songs as well as how those songs were recorded in the studio.” But more than just the craft of the music itself, these renegades dissented against the expected cultural look and feel of country music, “Rhinestone suits and new shiny cars, we’ve done the same thing for years,” Waylon Jennings plaintively sang. “We need to change.” At the time, the industry seemed to have the winning argument. In order to reach emerging markets, they reasoned, country music must sound more like the music Americans liked. The formula worked. The outlaws asked, referring to the legend of the past Hank Williams, “Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way?” but they lost the argument; the market knew what it wanted and the executives knew how to give it to them.

In their exile from Music Row, the outlaws were able, at last, to write the songs that seemed real to them. Turns out, they seemed real to others too. And, before long, steel guitars and bandanas would supplement, if not wholly replace, rhinestones and hairspray. Ironically, enough, the outlaws were not dissidents because they rejected country music tradition but because they loved it. They were, in the words of one journalist, “about the only folks in Nashville who will walk into a room where there’s a guitar and a Wall Street Journal and pick up the guitar.” Also ironic is the fact that the outlaws and their allies, with their songs that were dismissed by executives as too gritty or too intellectual or even “too country” would turn out to be the ones who could bridge the cultural form into other markets, not just with the outlaws but with their fellow travelers and those they influenced. Rednecks and hippies both loved Johnny Cash.

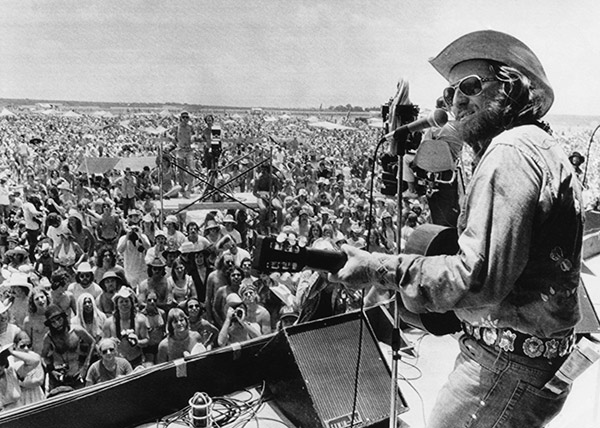

Willie Nelson opening the July 4th Picnic music festival, 1974. Everett Collection Historical / Alamy Stock Photo

The Nashville establishment was hardly wrong to wonder why they needed reform. They were, after all, selling records, making money. Kris Kristofferson writing songs based on Voltaire’s Candide did not seem to be the future. “The Opry audience was the Nashville Sound’s target demographic, and no one’s ever eager to fix a cash machine that isn’t broken,” one journalist observed. “But threads wear, imperceptibly at first, before they rip.” That’s true even for threads studded with rhinestone. The outlaw genre brought an infusion of change, without which the music form quite likely would have marketed its way into the very end it sought to avoid: a homogenous and aging cultural cul-de-sac with little relevance to those who were not already fans. That means, of course, the industry would have succeeded its way to oblivion. The art form required a revival of sorts, the kind of revival that needed at least a few outlaws to spur it along.

The outlaw experience is mirrored in many different art forms. Think of the development of jazz, which came to be, not in symphony halls, but in tiny clubs in New Orleans and Harlem and Chicago. The same could be said of the blues in the Mississippi Delta to hip-hop pioneers on both coasts. Mozart might even be thought of as “outlaw classical.” Marketing guru Seth Godin points to the Grateful Dead as an example within the rock music framework of what he calls appealing to the “smallest viable audience.” For Godin, the smallest viable audience principle isn’t about keeping “authentic” by adopting a “small is beautiful” mindset. It’s instead the realization that genuine change in art – and he defines “art” to mean any creative contribution to business, labor, and the crafts as well as to what we typically think of as art – comes about not by finding the lowest common denominator of what the “market” is thought to expect but by mattering a great deal to a relative few. If the contribution is worthy, the few will find a sense of belonging in their shared experience of that art and it will spread and grow. Usually – as in the case of outlaw country and many of the other musical expressions listed above – the change happens not just with newness but also with a reconnection to the best aspects of the past. A revival of anything often looks disturbingly different or doomed to irrelevance but really is a reconnection to roots so old they now seem new.

Revivals are paradoxically disruptive of the present while in continuity with the past.

In that, it seems to me, is both a parable and a warning for a church seeking revival – whether by “revival” we mean the mundane sense that these musicians meant it, a comeback, or in the larger, more supernatural meaning of the word. When many people think of evangelical Christianity, a form of revival imagery is the first thing that comes to mind. For some, that might be the brush arbors of the nineteenth century or the sawdust trail tent meetings of the early twentieth or the midcentury stadium crusades of Billy Graham and Luis Palau. Many others see in “revival” political overtones. They see purportedly evangelistic rallies that are about mobilizing voters, and they’ve seen political rallies in which soft music plays in the background at the end, as one almost expects the political figure to invite the crowd to walk forward to register to vote. Often when one hears an evangelical preacher thundering, “God send a revival!” or “We need awakening in this land!” what he or she means is “Let’s win the culture war.”

I find myself reluctant to use the word “revival” because the category serves for so many of my fellow American evangelical Christians as a kind of deus ex machina, a plot-twist that suddenly reverses secularization or any of the crises currently facing the church. “Well, we’re just going to have to pray for revival,” one might say. When pressed, some of these people seem to expect a sudden turnaround to the status quo normal in religious life to whatever period of time they knew before. Revival, for them, means “getting back to normal,” except with more people. History and demography seem to suggest otherwise. In a major study of American demographics, projecting major decline for Christianity, the demographers at Pew Research said that “there is no data on which to model a sudden or gradual revival of Christianity (or of religion in general) in the U.S.” They wrote: “That does not mean a religious revival is impossible. It means there is no demographic basis on which to project one.” A Bible-believing Christian would respond to such research by saying that it’s rooted in anti-supernaturalism, similar to a doctor telling a bone cancer patient that prayer will not help that person to heal. That’s almost right. But wouldn’t we want a physician at the very least to tell a patient that based on the normal trajectory, things do not look good? God can, and has, healed, but if the patient is abandoning chemotherapy to attend a faith healer’s rallies, one would want the doctor to tell the patient the most likely scenario.

Revival, in the Scriptures, is tied to the idea of resurrection. But not everything that is life-continuing is resurrection. Of this generation of white evangelicals, Robert P. Jones writes, “Their greatest temptation will be to wield what remaining political power they have as a desperate corrective for their waning cultural influence. If this happens, we may be in for another decade of close skirmishes in the culture wars, but white evangelical Protestants will mortgage their future to resurrect the past.” The danger, he notes, is forgetting this: “Like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, resurrection by human power rather than divine spirit always produces a monstrosity.”

Indeed, the fiery sword of the angel is placed at the entrance of Eden, the Bible tells us, to “guard the way to the tree of life” precisely because God did not want a twisted, fallen humanity to live forever in that state of death. An undying humanity – without spiritual life – is not resurrection life, after all, but a zombie story; the corruption and decay is animated and without endpoint, but still horrifically dead. Almost every high school student has read the short story, “The Monkey’s Paw,” about a wish for a dead loved one to be brought back to life. The terror comes about because that person is indeed made alive but just as he is – a decomposing nightmare. As Jesus warned a first-century church, “You have the reputation of being alive, but you are dead” (Rev. 3:1).

Nostalgia is, in and of itself, not a bad thing. In fact, it can well be the kind of “homesickness” that is the very kind of longing that is a signpost of God’s grace. What we call “nostalgia” can actually, though, be a desperation to get back to the past in ways that are dangerous, even deadly. In “revival,” many Americans fear that what evangelical Christians really mean is “taking America back” and to some era of the past, maybe the 1950s, to which few women or minorities would want to return. This is not an unreasonable concern. In the churn of American life right now, and religious life particularly, the pull to nostalgia is strong. One study showed that 71 percent of white American evangelicals said that the country has changed mostly for the worse since the 1950s, compared to less than half of black Protestants and only 37 percent of the religiously unaffiliated.

Just as with the pull of progressives toward more or less utopian views of the future, sometimes more traditionalist nostalgia is just that, a temperament shaped by the conservative tradition of skepticism toward change. But, as with the utopianism of the Left, this temperament can become violent. The so-called Great Replacement Theory is an example of the sort of conspiracy theory that can proliferate when longing for an idealized (and often imaginary) past is combined with anxiety about the future. Even when the nostalgia that drives us is not of this noxious sort (the kind that would wave the flags and erect the monuments of the Confederacy, for instance), it can still lead to what New York Times columnist Ross Douthat labels “decadence,” a situation in which the old order is exhausted and played out, yet prevents anything new from forming. In other words, as Waylon Jennings sang, “Lord, it’s the same old tune, fiddle and guitar; where do we take it from here?”

For all these reasons, “revivalism” itself – when disconnected from authentic revival – can make the situation worse and not better after all the tents have been taken down, all the sawdust swept up from the floor.

And yet.

Contrary to some critics of revivalism, of the Left and the Right, the decadence of “burned over districts” is not the whole story, or even the majority report, of what happened in revivals, many of which resulted in genuine “awakenings,” complete with sustained planting of churches. Whatever evangelicalism is, one common factor is an emphasis on the possibility of revival. Evangelicalism sees itself to be, after all, a revival movement in the broader Body of Christ. That sense of the possibility of revival is what has united Calvinists such as George Whitefield with Arminians such as John Wesley, and it’s what often defines or redefines a generation – as in the “Jesus movement” among the unlikely mission field of the hippies and surfers during the Vietnam War era. As with the altar call, “revival” can mean a mechanized, manipulated marketing campaign – or it can mean something the Scriptures speak often about, the power of God in stirring a community – and not just an individual – from death to life.

Evangelicals – along with other Christians – often point to the account of the prophet Ezekiel standing over a valley of disconnected skeletons, and being asked “Can these bones live?” (Ezek. 37:1–14). The answer from the prophet is “Lord, you know.” The mystic imagery of the revival of Israel does indeed happen, and happens in precisely the way we see it happen over and over again in the Bible – through Word (Ezekiel is commanded to “prophesy” to the bones) and through Spirit (the breath of God reassembles the rattling bones and gives them the life to stand as an army). The result of that revival is a new unity – what seem to be irreparably divided kingdoms repent of sin and find their identity under the kingship of the son of the House of David (Ezek. 37:18–28). This is still, maybe even more than in years past, a worthy goal.

To get there, though, evangelical Christians in this time of confusion and disorientation must discern what precisely it is that we are seeking to “revive.” If that is merely the nostalgic restoration of some previous (and mostly imaginary) golden age of Christian influence and morality, then no revival is possible. An alcoholic cannot heal simply by imagining the gauzy days of his or her youthful sobriety. He or she must ask what about that sobriety led to the drinking in the first place. The goal is not to “get back” to something but to seek renewal for the future, a renewal that might have continuity with the past but will often look strikingly different from it.

In lasting revivals of the past, the revivals are never a replay of what had gone before, repeating the same methods and propping up the same institutions. Nor were any of these revivals the sort of “modernizing” theological pivot that some on the Left often propose, that Christianity must “change or die” by moving beyond the “outdated” fundamentals of the faith. Revivals are paradoxically disruptive of the present while in continuity with the past. For all the ways that the evangelical emphasis on the Protestant idea of the “invisible church” can degenerate into the sort of anti-institutionalism that can turn Christianity into an ideology rather than a locally lived life, key aspects of this model have proven vitalizing and regenerating of actual church structures. Those finding connection beyond their church and denominational borders often are able to return to their own communities with a renewed vision for what’s possible for the future, that the decline of existing churches or networks need not be inevitable. At the same time, genuine revival has always come through after a time of intense disorientation and even what seems to be a tearing-down of the status quo….

A “remnant” is usually the way that God brings about revival. He usually pares a people down, clears away the field, prunes the branches, and then starts again. The pattern is order, disorder, reorder.

For all the flaws of the evangelical emphasis on revival, the beauty of it is that it, first of all, doesn’t give up on the possibility of God acting. God can do a new thing. What’s more, a true revival, while corporate – in the sense of bringing new life to a whole body of believers – retains the sense of the personal. “Lord, send a revival,” the old song goes, “And let it begin with me.”

Source: Excerpted from Losing Our Religion: An Altar Call for Evangelical America by Russell Moore, published by Sentinel, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2023 by Russell Moore. 205–222, 227–228.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Noel McMaster

Beyond the "order, disorder, reorder' of Richard Rohr/George Marsh, and beyond the biological "change or die" maxim there is the "change and die" of an evolutionary paradigm. Juan Luis Segundo's, "An Evolutionary Interpretation of Jesus of Nazareth" pursues the binary of entropy/negentropy in creation as it plays out to a subtheme, "execution never fully realises intention". But the Band plays on.

George Marsh

For a book-length treatment of the pattern "order, disorder, reorder"( cited in the next-to-last paragraph) readers can go to Richard Rohr's book, The Wisdom Pattern. Returning to fundamentals, wellsprings, is the key in the advice "repent," which literally means "think again."