Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Behold the Glory of Pigs

-

Polyface Logic

-

Nature Is Sacred Stuff

-

Editors’ Picks Issue 10

-

Poem: An Apology for Vivian

-

Stewarding Mercy

-

Learning to Love Goodness

-

Who Invented Thirst and Water?

-

Muhammad Ali

-

Are Humans Sacred?

-

Islands

-

Readers Respond Issue 10

-

Consistent Life Network

-

Death Knell for Just War

-

Remembering Daniel Berrigan

-

My Return to Iraq

-

Pursuing Happiness

-

The Gospel of Life

-

Building the Jesus Movement

-

Behind Prison Walls

-

Womb to Tomb

-

Insights on the Gospel of Life

-

A World Where Abortion Is Unthinkable

-

Gardening with Guns

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

Curled up on a chaise lounge that had been adapted into a daybed, Bill was obviously not at peace. Pale and drawn, he moved slowly, grimacing, with the occasional twitch and jump in his limbs. As a community health nurse working in London for a Christian charity that ministers to AIDS patients, I had seen these symptoms before.

“How long has he been like this?” I asked Ian, a bespectacled man in his mid-thirties who had introduced himself as Bill’s partner.

“For the last couple of hours, really. More or less since he got home,” Ian replied, his anxiety and weariness barely disguised. “Can you do anything for him?”

There was plenty of reason for worry. Bill, who had an AIDS-related lymphoma, had just been discharged from a hospital where he had been admitted for a type of pneumonia common among AIDS patients at the time. The hard truth of the situation was that he had come home to die.

Ian told me that he and Bill had lived together for about ten years. Both worked in the media and had enjoyed successful careers. When Bill had been diagnosed as HIV-positive eight years earlier, they had coped and even thrived for a while. But once Bill developed AIDS-related illnesses, his freelance work had dried up, and Ian had had to be both caretaker and sole breadwinner. Those friends who had not dropped out of contact mostly lived too far away to lend anything more than moral support, while both their families wanted nothing to do with them.

Two hours later, I had set up a new diamorphine pump that would help Bill settle for the night and grant Ian a few hours’ sleep. Bill smiled as he held my hand and said thanks. Ian hugged me grimly and wordlessly as I left.

The next day I came by in the late morning to check that they were OK. Bill had slept through the night and appeared less drawn. Ian also seemed more rested, but I sensed that he was not at ease. As I set up a new syringe driver in the kitchen, he came in and gently shut the door so Bill could not hear. “Is he going to get more like he was yesterday evening?” Ian asked.

“As long as we can keep his symptom relief working, he will be comfortable,” I replied. “But he is going to get steadily weaker – I don’t think he is going to make any significant recovery from this illness.”

Ian drew a ragged breath. “Can you give him all the morphine in one go?”

“That would suppress his breathing and he could die,” I replied, suspecting what was coming next.

“I don’t want him to suffer. Can’t you just ... you know, fix it ... so he drifts off peacefully?”

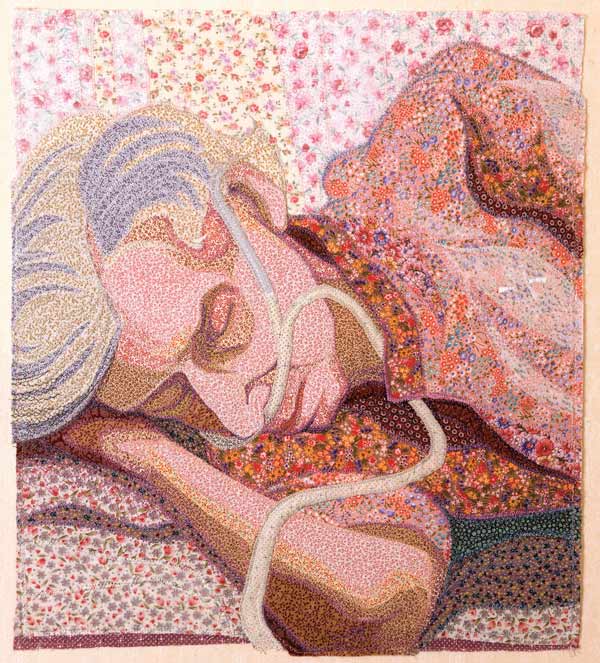

Deidre Scherer, Late May, 1990, thread on fabric, 15 x 13"

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

The Final Moment

I have cared for many men and women at the end of their lives, and try as I might, not all of my patients have had what one could call “a good death.” Some things are just out of one’s control. But I do know that not one of my patients suffered for want of good care. I knew lots of Bills who had poorly planned discharges and who needed lots of extra support when they got home.

I experienced this firsthand with my own mother. She was discharged from hospice with no one at home to care for her. My sister had to drop everything to travel over a hundred miles to Mum’s house. Within hours my sister was on the telephone begging me to come and help her after Mum fell while trying to get off the toilet.

My mother’s condition nosedived, so I relocated my very young family and my work for the next six weeks as we cared for her in her last days. The support we got from friends, family, her doctor, and community nurses made all the difference. As a result, my mother ended her days seeing her granddaughter taking her first steps. My father-in-law, an Anglican minister, visited so that she could share communion and worship from her sickbed one last time with her family. She died surrounded by her children, family, and friends in the bedroom she had shared with my father, who had died two years earlier, in the house in which she had been born seventy-two years earlier. It was what I would call a good death.

We are meant to be burdensome to one another.

For Bill and my mother, having the people they loved at hand was the “symptom control” they most wanted. I could set up diamorphine syringes to take the pain and nausea away, turn them regularly to avoid pressure sores, and feed them food they could tolerate and enjoy. All this is essential, basic, and good nursing care. But it was having the people they loved nearby, and sensing that their own lives still had meaning and value, that really made the difference. For my mother, ending her days in the knowledge that she was going to be with her Lord brought tremendous comfort.

I cared for Bill for only a few more days before he died naturally. Ian soon saw that Bill was comfortable, and that what he wanted more than anything was to say goodbye to those closest to him. Bill’s family finally came to visit, as did many of his dearest friends, and his dying days were not spent in isolation.

When I saw Ian after the funeral, he admitted that if I had let him have his way that Saturday morning, overdosing Bill with diamorphine, this would have denied Bill the chance to say goodbye. It was a better end than Ian had feared, and in the midst of his grief he had the satisfaction of knowing that Bill had died knowing he was loved.

Most of the distress people experience at the end of life is ultimately spiritual: that sense of being lost, isolated, fearful, and unsupported; the fear of being a burden on your loved ones, and of uncontrolled symptoms; the grief that your entire life, with all your loves, your hopes, fears, dreams, and ambitions has come down to this small room, this bed where you are going to end your days. And possibly above all, there is the fear about what comes next – oblivion? Some kind of afterlife? In a post-Christian West, there are no longer any accepted answers or structures to help people contend with these questions.

The Burden of Being Human

Around the world, various groups are calling to make it legal to help end someone’s life in the case of terminal illness. As a nurse who has worked with the dying, I sympathize with the natural desire to avoid unnecessary suffering at the end of life; it’s the same impulse that undergirds palliative care and the hospice movement.

There is, however, a spiritual despair at the heart of this call for assisted dying. In a society that celebrates youth, vitality, beauty, and self-determination above all else, the fear of losing these is almost intolerable. Then only despair remains. One’s last act of self-determination becomes to end one’s own existence while one still has the autonomy to do so.

How different is the Christian understanding of the self. Scripture teaches us that we are not our own: we are Christ’s (1 Cor. 6:19–20). As such, our lives are hugely valuable. It is not for us or anyone else to determine the timing and nature of our deaths.

Furthermore, we are not autonomous individuals, but part of a community, an interdependent body (1 Cor. 12:12–13). When one part suffers, all parts suffer. When one part rejoices, all rejoice. This is a community where we are enjoined to “bear one another’s burdens.”

Data published by Oregon’s assisted suicide program over the last decade shows that the vast majority of patients cite the fear of being a burden as one of their main reasons for ending their lives early, alongside fear of loss of control and independence and the feeling that life has lost meaning and joy.footnote

Yet scripture tells us that we are meant to be burdensome to one another (Gal. 6:2). I was a burden to my mother at the start of my life. I saw this as I cared for her and my eight-month-old daughter at the same time. I had to feed both of them, change their diapers when they soiled themselves, soothe them to sleep when they were distressed. My mother had done all of this for me, and now I was doing it for her. There was a natural symmetry. And while I wish my mother had had many more years of life, I would not have given up the chance to be with her and care for her in those final weeks. It was one of the most profound privileges of my life.

This mutual burdensomeness is part of what makes us human. God himself shares in this – bearing our sins and suffering on the cross (Isa. 53:3–5). The Incarnation reveals another depth of human existence, for as Jesus was once a helpless baby, needing to be fed, washed, and changed, so he was also a dying man who needed care and company in his final hours. In taking on our humanity, God endowed every helpless baby and every dying person with the same value and dignity. In caring for our children and the dying, we care also for him (Matt. 25:35–40). It is one of the most remarkable wonders and mysteries of the Christian faith, and it is an experience that transformed me as both a nurse and a father.

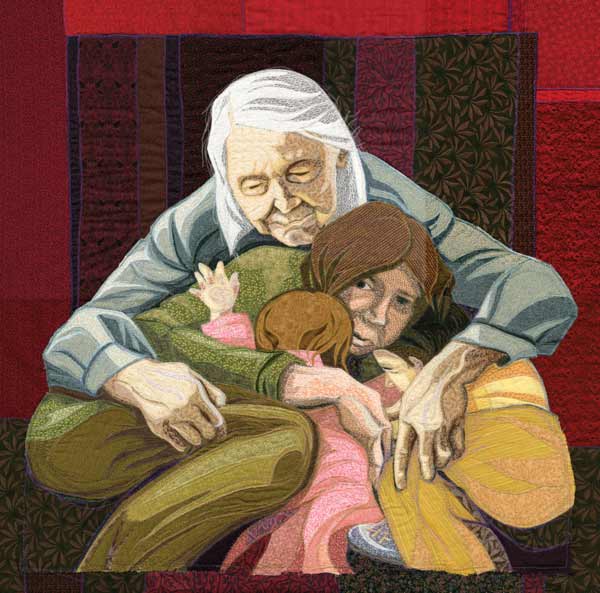

Deidre Scherer, Huddle, 2010, thread on fabric, 34 x 34”

Daring Peace

When advocates for assisted dying argue that it is a lack of compassion that drives caretakers like me to oppose their agenda, we have had to constantly, compassionately, and patiently argue back with the facts. People do not need to die in pain and with uncontrolled symptoms. Allowing doctors or nurses to kill certain groups of people, or to assist them in killing themselves, will eventually lead to opening the same “option” to anyone who feels that his or her life is not worth living. We are already seeing this happen in the Netherlands and Belgium, where voluntary euthanasia legislation has slowly been extended to those with dementia, to those in comas, to infants and children, and most recently to those struggling with past traumas, anxious about the future, or simply tired of living.footnote

The consequences of removing these legal constraints are far-reaching. The vulnerable feel pressure (real or imagined) to stop burdening their families and society by ending their lives. Governments, healthcare systems, and insurance companies faced with mounting costs start to see assisted death as a cheaper, more “humane” alternative to long-term care. The symmetry of mutual burdensomeness is lost, and society loses its soul as it kills off those it deems unworthy of life in the name of autonomy and compassion.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote, “There is no way to peace along the way of safety.” Some of my colleagues have been vilified in the press and social media for taking stands against euthanasia. Yet time and again, our arguments have won over our legislators, much of the serious press, and healthcare professionals.

I well remember the look on the face of my CEO here at the Christian Medical Fellowship when, after having successfully helped to defeat two assisted-dying bills before the Westminster and Scottish parliaments, he received a call that another, newly re-elected MP would be bringing yet another bill before the House of Commons after the British general election in May 2015. Just as we thought the battle was won, the war began again. Fortunately, the bill went nowhere. After long and serious debate, with great speeches on both sides, the house overwhelmingly voted down the proposed legislation by a three-to-one majority, stalling this push in Westminster Parliament for at least the next five years.

To care and show compassion is an essential mark of discipleship (2 Cor. 1:3–7). Equally, discipleship demands the willingness to stand up and speak for truth, for the vulnerable, and for the marginalized (Isa. 1:17). As a nurse and as a Christian, I must do both. I cannot credibly do one without the other.

To give the best care, to enter into the world of the dying and their loved ones, to share those last days and help them have peace, to give comfort and meaning through those days – these are great privileges and responsibilities. But by that same token, we must work to ensure that the dying are not encouraged to prematurely terminate their lives in the mistaken belief that they are escaping suffering. Rather, it’s our task to make sure they know that they, far from being unwanted burdens, are valued and loved to the end.

The artist Deidre Scherer is a pioneer in her medium of thread-on-layered-fabric. She has created two narrative series – The Last Year and Surrounded by Family & Friends – that promote an open dialogue about aging and dying as a natural part of life. Visit dscherer.com.

The artist Deidre Scherer is a pioneer in her medium of thread-on-layered-fabric. She has created two narrative series – The Last Year and Surrounded by Family & Friends – that promote an open dialogue about aging and dying as a natural part of life. Visit dscherer.com.Images of her artwork in this article are © Deidre Scherer and used by her permission.

Footnotes

- Oregon Death with Dignity Act: 2015 data summary (pdf), page 4; Oregon Public Health Division, February 4, 2016.

- Scott Y. H. Kim; Raymond G. De Vries; John R. Peteet, “Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide of Patients with Psychiatric Disorders in the Netherlands 2011 to 2014,” JAMA Psychiatry 73, no. 4 (2016): 362–368. See also Steve Doughty, “Sex Abuse Victim in Her 20s Allowed to Choose Euthanasia in Holland after Doctors Decided Her Post-traumatic Stress and Other Conditions Were Incurable,” Daily Mail, May 10, 2016.

Steven Fouch

Steven Fouch

After years working as a community nurse in London, Steven Fouch now works with the Christian Medical Fellowship in the British Isles as a speaker and writer on spiritual, ethical, and professional issues in nursing and healthcare.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Joella Critchfield

I have worked in hospice as well as being able to say good bye to my own sister as well as to a neighbour, whose whole family (Russian immigrants) got together and invited neighbours to say good bye when they knew the old father/grand father was reaching the end. But my mother, who had severe dementia and lived hundreds of miles away from me and I had no funds or ability to move to be near her, died of dehydration because there was no one who paid attention to something as basic as not drinking when she had thrush. There is a huge population of dying people who have no one who can carry the burden for them to die a nice natural death with loved ones around them. I agree with the opinion that each person should be allowed to choose for themselves. There are also enough cases where the family graciously carries the burden suffers terribly because of that burden.

Lila Wagner

Sometimes it's difficult for the layperson (and maybe the medicos?) to see where pain-relief becomes over-the-top-leading-to-death medication. My husband with lupus was on very heavy pain-relief medication and most of his digestive tract had shut down as he approached death. Did he die a natural death or did the pain medication finish him? As a layperson it's hard for me to say, but I know that he died quietly after he had talked long-distance with our daughter. It was the first time I witnessed death.

Sue Doohan

I think the deciding factor is the will of the patient. If there is certainty the patient is in the process of dying, I have no problem with them choosing to die before the process becomes an ugly memory for those left behind or to say enough, they don't want to continue suffering when there is no purpose in it. I have also seen dying people hold onto this life until those who love them are ready to accept the loss. This to me is a decision best made on a case by case basis.

Jacqueline John

This is so excellent, these are the sufferings that transform us all by the love of Christ. Jesus didn't say life would be easy he said it would be difficult but that he would never leave us or forsake us. Thank you for this article so helpful for those of us who have aging parents.

Karen Moresby-White

Amazing article, this has helped me sort out the issue in mind. always knowing it was not God's will, but now understanding why. Thank you.

Kerry Brockhagen

I can't say that I agree. In my (humble) opinion, this decision to end one's own life is up to the individual. I say this with the full realization that this may result in some people terminating their lives before others think they should. I say this from the perspective of a person with major (clinical) depression, whose life was almost ended prematurely not once, but twice. I am eternally grateful to God that He saw me through those times, but strongly feel that I should have the option to end my own life in the event that I am not, barring a miracle, going to get better. It is my decision, and my work to resolve this with God. While I would never want to be faced with this decision, and would not wish this decision on anyone, I strongly feel that it is the decision of the individual. With that said, your article is inspiring and beautifully written, and I thank you for sharing your opinion.

Craig Willers

I am Mentally Ill and know firsthand what it's like to desire death in my misery. However, it's been 35 years since my diagnosis and life now is light years away from my initial torture and struggle. I sometimes forget the greats strides I have made when I feel the call of death and weariness in my heart. Jesus was "sorrowed to the point of death" in the Garden of Gethsemane and that leads me to believe he knew exactly how I feel and has the greatest compassion for myself and others like me. "Hope deferred makes the heart sick" but also "There is hope as long as you are in the land of the living". We must cling to hope and draw strength from God and those around us. My wife is a Hospice Nurse and I'm proud to be the partner of someone with such deep compassion. Thank you for your article.

MICHAEL NACRELLI

The Canadian Supreme Court recently declared euthanasia a fundamental right, and the implementation guidelines crafted by the Canadian government leave little room for Christians to continue practicing medicine in good conscience. If Hillary Clinton gets to pack the SCOTUS with her nominees, we can expect to see a similar outcome here within the next decade.

Stewart Patrick

Gosh you guys & gals at Plough come up with some stunning testimony articles. This one so timely and I hope will be read by more folk in my church.