Subtotal: $

Checkout-

At the Welcome Table I

-

At the Welcome Table II

-

Love Is Work

-

How Shall We Farm?

-

Why Yemen Starves

-

Digging Deeper: Issue 20

-

Cloth and Cup

-

Level

-

Editors’ Picks Issue 20

-

The Necessity of Reverence

-

A Book to End All Walls

-

Edna Lewis

-

The Dead Breed Beauty

-

Table Fellowship

-

Covering the Cover: The Welcome Table

-

Restoring a Creek

-

What I Stand For Is What I Stand On

-

Feasting in Kurdistan

-

The Birthday Party at the End of the World

-

From Farm to Feast

-

Readers Respond: Issue 20

-

Family and Friends: Issue 20

-

Streams in the Desert

-

The Boy and the Bull

-

This Is My Body

-

The Greatest Thing Since Sliced Bread

-

The Ground of Hospitality

-

Beating the Big Dry

When we moved to northern Kenya to develop a modern farm early this century, what I first thought I saw was a pristine Garden of Eden. On high plains I walked among an abundance of wildlife – predators and herds of elephant, zebra, eland, oryx, giraffe, and antelope. Here were savannahs and open woodlands, an arid wilderness without fences.

At first I imagined that any type of human activity I embarked on as a farmer would ruin this paradise. But I was ignorant. Our land was an Edenic wilderness only at first glance. On the horizon, my neighbors were pastoralists, tribespeople who tended cattle, sheep, goats, and camels in a semi-nomadic lifestyle going back millennia. Or they were modern commercial cattle ranchers, most – like me – descendants of colonial British settlers. Or they were conservation groups such as The Nature Conservancy, which invests in this part of Kenya to establish sustainable ways of protecting wildlife and providing impoverished communities with education, health, and job opportunities.

I discovered human marks already etched across the landscape. Prehistoric hand axes and obsidian tools littered the ground. Out rambling, I stumbled on cairns – stone circles, burial mounds, monuments – some isolated, others in sentinel rows. They overlooked views of mountains or water, to me a sign across millennia that we share a love of nature. On local cave walls were tableaux of wildlife, human figures, and cattle. For these were some of the first pastoralists.

Our land was an Edenic wilderness only at first glance.

From about 3000 BC in the district, our hunter-gatherer ancestors began tending cattle, sheep, goats, and camels. The landscape was forested until then, but livestock keepers used fire to create open grasslands. Livestock fertilized soil, improving pastures that now sustained not just domestic animals, but also multiplied the wild mammals we associate with today’s African savannahs.

Almost until the present day, pastoralists and livestock shaped our local landscape alongside wildlife. Only with the arrival of colonial British ranchers did that change. Farmers regarded wildlife as competition for grazing. During the 1940s wild creatures were wiped out to feed Italian prisoners of war in camps around the base of Mount Kenya. A decade later, writer Elspeth Huxley recorded that all lions in our area had been exterminated.

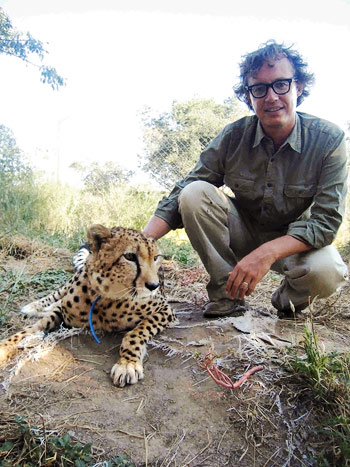

The author

Attitudes reformed in the 1980s. Cattle ranching in Africa is tough, and farmers saw the advantages of conserving wildlife because they could start tourism businesses to supplement meager incomes. Conservation was becoming broadly popular in Kenya, where sport hunting had been banned. If you leave nature alone, it tends to recover swiftly – and now that people were not out to relentlessly kill them, lions and other creatures naturally recolonized our landscape. Within a few years, ranchers and pastoralists were living in relative peace alongside predators and other game. In fact, our commercial ranchers and relatively poor cattle-keeping tribespeople are more tolerant of lions than farmers in North America are toward wolves being reintroduced in national parks.

During the days our livestock are herded across the open grasslands, since we have no paddocks. At evening they are brought into a boma, or night enclosure, protected by a stockade of acacia thorns and drystone walls. We have learned to adopt traditional pastoralist methods, and if left out in the field overnight I would say my cattle have a 50 percent chance of being killed and eaten by predators. As it is, in fifteen years of keeping cattle, I have lost only one calf to a lion during the day, while a handful have been killed at night. These are losses I can tolerate – though I found it harder to take the slaughter of twenty-five sheep in leopard raids during a string of nights over the last year. While breathing deeply, I try to compare this disaster to having a fox in a chicken coop in Europe. That does not cheer me up entirely, because our poultry are already harassed – not by foxes, but by the occasional giant spitting cobra: eight feet long, highly venomous, and hungry for eggs.

You could say we farm grass, not cattle. Everything comes down to conserving bush pasture.

Our sometimes predator-harassed farm is semi-arid, at high altitude, with cyclical droughts. I rate myself not in how I respond to wet seasons, when pastures are as green as Ireland and any fool can come by success, but in the ways we tackle the very dry years when it hardly rains. Our cattle are entirely grass-fed. You could say we farm grass, not cattle, and everything comes down to conserving bush pasture. Alongside the wildlife that wanders in and out, we figure on stocking one adult cow to fifteen acres of pasture. If there were no wild animals, we would have much more grass and could stock twice as many cattle. That would improve our income, but like cattle, wildlife species also benefit the land.

Zebra will eat rank grass and weeds the cattle spurn. Browsing species nibble at separate layers of the bush: giraffes at the top, elands below that, then gerenuks, then other antelope. Elephants bulldoze trees but also clear bush to make way for grass. In other places where the wildlife is killed off or excluded by fences, I have seen invasions of noxious weeds and massive encroachment of bush that strangles pasture.

My own belief is that getting rid of wildlife probably brings no benefits, whereas biodiversity here helps sustainable farming of the sort pastoralists have been developing for centuries.

Indigenous traditions of pastoralist husbandry inspired the choices of animals we keep. On our farm, I have bred a stud herd of Borans, zebu-type cattle with humps and dewlaps that are perfectly adapted to our arid conditions. The Boran is an entirely indigenous beef breed, selected a century ago by European ranchers from indigenous African stock whose excellent qualities had been nurtured by pastoralists for fifteen hundred years or more. Our district is also sheep country, and the best local breed is the Dorper – a cross between the Dorset Short Horn ram from the United Kingdom and the Blackhead Persian, an indigenous breed so old you can see the animal depicted on the walls of ancient Egyptian tombs. Together the Boran cow and the Dorper sheep combine pastoralist traditions based both on millennia of survival and on modern European science and selective breeding.

Some farmers in our area also own dromedary camels. These are resilient creatures, relatively easy to keep, though slow to breed. Their milk is low in cholesterol and fats, high in vitamins, and fetches a handsome one dollar per liter on the local market. News of the benefits of camel’s milk is spreading and we hear supplies are now being sold in European supermarkets.

Donkeys, I discovered a long time ago, are happy creatures that will perform like small tractors and almost never break down if you treat them kindly. When we first started on the farm in 2003, we pitched a tent and donkeys carried water in jerry cans from a spring. Later the donkeys carried building sand and cement while we were erecting houses and barns.

To make ends meet, I decided to plow up a portion of the farm’s virgin soils to grow crops, potentially a better source of income than cattle. Like some other ranches committed to conservation, I saw sacrificing some of our land to cultivation as a way to conserve the majority of it. In a way it was exciting – we were turning over new ground like the mid-nineteenth-century sodbusters of the Great Plains. At the same time I felt guilty, knowing that crops would displace a spectrum of species from cheetah (seven thousand remain globally) and reticulated giraffe (only nine thousand survive). As a beekeeper with fifty hives, I lay awake at night wondering how I could go over to the dark side of applying pesticides and glyphosate. My compromise was to grow fodder crops without chemicals. Yields were lower, but the cultivated pasture became a home to more game, not less, alongside my cattle, so I believe it enhanced both productivity and biodiversity.

Growing fodder crops like hay gives me a commodity to market to my pastoralist neighbors. I also sell them Boran bulls and Dorper rams, and this week I am even negotiating to supply a man with four stallion donkeys he wishes to use to carry water. Supporting education for children in the area and trading do not persuade the young men among the pastoralists to stop raiding my cattle – and why should I be surprised, since rustling has been an honorable pastime since the days of the ancient Greeks? Hours after his birth, the boy god Mercury stole the bulls of his uncle Apollo, the sun god, and tried to confuse his pursuers by placing the animals’ hooves on backwards – but was caught and only got himself out of a scrape by making his uncle a lyre that produced beautiful music. The young warriors from Samburu families that neighbor us today do not seem greatly different.

Many times we have had cattle raids and I have trekked after my stolen animals with our herders, sleeping for several nights on the hard ground next to the raiders’ and cattle’s tracks. Strange as it may seem, those cold evenings with the farmhands, sharing between us a few cups of water, have been some of my happiest times as a man. Except for seven cattle that were lost completely, I always managed to track them down and persuade the elders to make the young men return the stock.

Apart from that, young warriors might also occasionally hunt lions to prove their manhood, but at least they do not usually hunt other species of wildlife for meat or ivory or horn. They have traditionally believed hunting for wild creatures is beneath them as honorable men, who should only gain wealth through cattle. And the belief is that cattle are gifts from God, or Ngai, specifically to the Samburu. While drinking cups of milky tea in the cattle camps up the hill from my home, I have often heard stories that the Samburu once inhabited the planet Venus. That was their home until the surface of that world had become so overgrazed that Ngai made a rope that he slung from Venus to the planet Earth. Down the rope the Samburu people climbed, arriving in a wild Garden of Eden. To help them on their way, Ngai sent herds of cattle down to the new homeland, to be a source of milk, blood, meat, and wealth for the pastoralists evermore in the wilderness.

I find consolation in that creation story, because it tells me that since the arrival of humans in this landscape where our family so enjoyed building up a farm, the destiny of humans and cattle have been entwined. But there’s a warning there, too: we must care in this world for nature, the pasture, and the wildlife, in order to avoid becoming another overgrazed and denuded planet.

All photographs by Aidan Hartley. Used with permission.

Aidan Hartley writes the Wild Life column in the Spectator. His first book was The Zanzibar Chest; his book about ranching in northern Kenya will be published in early 2020 by Grove Atlantic.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.