Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Perfectly Human

-

Let Me Stand

-

All Sorts of Little Things

-

The Measure of a Life Well Lived

-

Siegfried Sassoon’s “Before the Battle”

-

Editor’s Picks Issue 17

-

Our Task Is to Live

-

To Be Plucked by a Strange or Timid Hand

-

The Beguines

-

Carry Me

-

The Soul of Medicine

-

Readers Respond: Issue 17

-

Family and Friends: Issue 17

-

The Hunter

-

Beyond Racial Reconciliation

-

Science and the Soul

-

Money-Free Medicine

-

Patient Perspective

-

On Being Ill

-

On Eternal Health

-

Adirondack Doctor

-

Christ the Physician

-

What’s a Body For?

-

Begotten Not Made

The End of Medicine

Euthanasia and the campaign to “take death back”

By Reuben Zimmerman

July 16, 2018

Available languages: español

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

On May 25, 2017, the New York Times published a front page article about a man in British Columbia who planned his own wake – a living wake, that is – and who, after most of his friends had left, succumbed to a lethal injection administered by his doctor.

The article is well-written, and convincing. There is a sick man who doesn’t have much longer to live, or who (more accurately) is tired of living with his illness. There are eagle feathers and prayer shawls, and good food and hugs and tears. People light candles and present blessings and talk about “taking death back.” But someone is going to be killed, and even the doctor who administers the deadly drugs to the man acknowledges as much. Though “that’s not how I think of it,” she says adamantly. “It’s my job. I do it well.”

Other examples abound. There is the story of the elderly couple in Oregon who recently chose to go together: after sixty-six years of marriage, including years as medical missionaries in India, they decided that old age and infirmity – between them, Parkinsonism, heart disease, and cancer – were too much to bear. After their family documented their exit on video, they were duly hailed as brave exemplars of the new way to die.

Then there is Brittany Maynard, the twenty-nine-year-old woman in California with an inoperable brain tumor whose struggle for the “right” to die led to assisted-suicide legislation there and in other states. Promoted as a hero by the likes of People magazine and CNN, she moved to Oregon to obtain the drug cocktail by which she ended her young life.

But it’s not just cancer and neuromuscular disability that is driving people to opt out of living. Increasingly, it’s depression – “exhaustion” with life – and now, in parts of Europe, even just old age. What is going on, and why?

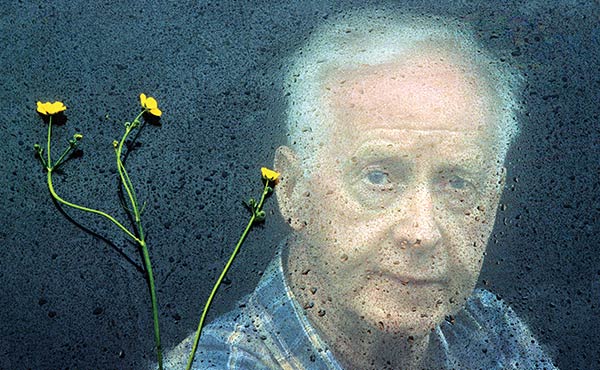

Untitled, Scott Goldsmith Photograph by Scott Goldsmith. Used by permission.

Who Is Pushing for Euthanasia?

Having cared for the sick and dying for over twenty-five years, I can well understand what drives people to take matters into their own hands. Despite everything modern medicine has to offer, it has not yet conquered death, nor the suffering that sometimes precedes it by decades, and it is not likely that it ever will. Even as we have learned to successfully treat childhood leukemia and eliminate polio and diphtheria, we have not yet found cures for the scourges – arthritis, heart failure, incontinence, or insomnia – that seem to mar old age for so many people, even those who live in the most attractive neighborhoods and who don’t have to worry about their finances.

Data from the states where assisted suicide is now legal suggest that people aren’t signing up for lethal prescriptions just because they’re in pain. Instead, it’s because they are afraid of “losing control” – because they are lonely, afraid, or worried that they have become a burden on their caregivers – or simply because they want to do things “their own way.” In California, for example, the vast majority of people who have taken their own lives under the new right-to-die law have been well-educated white seniors who were already receiving palliative or hospice care. Almost all of them also had medical insurance, so cost was not necessarily an issue. And in Canada, one doctor who is also a longtime supporter of assisted suicide says that the patients who request his services come from a particular personality type: they tend to be the “doctors, lawyers, captains of industry, and successful business people” who “always get what they want.”

Too often, we have embraced our culture’s false gospel that happiness really depends on the absence of inconvenience and suffering.

Given the spiritual emptiness and materialism that often characterize modern life, along with the presumption that human happiness depends primarily on mobility, independence, and self-determination, it is understandable that we should have come to this place. But if it is understandable, it is also an indictment on those of us who call ourselves Christians. Too often, we have embraced our culture’s false gospel that happiness really depends on the absence of inconvenience and suffering. From there, it’s a small step to seek to bypass the infirmities of old age and disease by engineering one’s own death.

The Place of Bravery

For centuries, human beings fought against death with everything they had. Death was unavoidable, but it was still something to be feared and delayed. Now, however, we are suddenly facilitating it, even embracing it, as a solution to the pain and the problems of living. The reason for the shift, we are told, is that advances in modern medicine, especially life-support technologies that can postpone death indefinitely, have fundamentally changed the moral calculus. The old Hippocratic ban on causing a patient’s death must supposedly yield to today’s realities.

But even if suicide or euthanasia is described in comforting euphemisms and carried out on a comfortable bed in the privacy of our homes, is it really the solution to these dilemmas? Those of us who see the body as more than a mass of quivering cells must protest that it is not. If we are spiritual beings, made in the image of God, then our reasons to keep living can never depend completely on physical ability or the absence of discomfort.

All of us long for personal fulfillment, for happiness, and for good health, and we also want our lives to be meaningful. And yet such meaning cannot be measured by the absence of hearing aids and wheelchairs and oxygen tanks; rather, it must result from the knowledge that we have spent our best years in the service of God and our fellow human beings – that our lives were not lived solely for ourselves, but were in some way poured out for others.

It also depends on faith, which the apostle Paul defined as the assurance of things hoped for, and the conviction of things not yet seen. Many people today mock faith as the property of unenlightened zealots. And yet the real enlightenment is to know that with faith, we can boldly enter the realm which in this life we do not see or know. Faith can bring us a peace that surpasses all human understanding, a confidence that the throes of death are overcome not by a syringe of midazolam but by embracing what has been laid on us, trusting that it will not be more than we can endure.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

My own wife, Margrit, was an example of such faith. Stricken by small bowel cancer at the age of forty-three, she fought back for twenty-two months until it was clear that she could not win. At that point, she faced death squarely, and with a calm bravery that came from far beyond herself.

Letting go wasn’t easy: she was in the prime of life, as were our five children, all between the ages of twelve and nineteen. So she shed tears over missed graduations and weddings, over the grandchildren she would never see, and over the fact that she would leave me a widower at forty-seven. But she also looked back with joy and gratitude at the life she had lived as a wife and mother and nurse: at the many births she had attended, the hundreds of patients she had cared for, and the thousands of lives she had touched, knowingly and unknowingly, over many years.

She was ready to go because she had served, and her years of service to others now allowed her to rest with a sense of peaceful (if humble) accomplishment. Thus when I asked her, weeks before the end, if she was afraid, she could answer, “No, I don’t think so. I believe Jesus is coming to fetch me.”

We celebrated our twenty-fifth wedding anniversary in December 2014, and by January 2015, she could manage only yogurt and broth. By February it was weak tea, fortified with honey and cream. By March, she was gone. Despite receiving the best care medicine could offer, she still suffered terribly in her last ten days: malignant small bowel obstruction, which invariably leads to vomiting, is one of the most difficult situations palliative medicine experts have to deal with. Still, she never once flinched or complained, and instead radiated peace and love, often through shining eyes, until her last agonizing breath.

She went Home surrounded by her family: her parents, my parents, her siblings, and our children. There was singing, and there were prayers, and plenty of tears, and we prayed often that she might somehow be released, but we never once contemplated pushing things along or taking things into our own hands. Like those willing to await the birth of a baby, we waited for God’s moment, knowing that just as those gathered around a laboring woman rejoice when the child bursts out of the womb, those waiting for Margrit in the world beyond would break into singing when she crossed her Jordan.

It wasn’t just her faith that held her through: it was the love of the community to which we belong.

She was blessed with a strong faith, and yet it wasn’t just her faith that held her through: it was the love of the community to which we belong that carried her, and our family, through the most difficult hours. She received expert medical care, but more than that, she received pastoral care in the form of house calls and prayers, songs and services. From the moment she was diagnosed with cancer, people rallied around her. Children brought flowers, old friends dropped by to reminisce, acquaintances we hardly knew dropped in with baskets of food. But what of the thousands of people who lack such love? And could it be the absence of this love that is driving so many of them to take matters into their own hands?

Dying in the Church

In 1651, George Fox, founder of the Quakers, famously told Oliver Cromwell’s representatives that he wished to live such a life that would “take away the occasion for war.” Might we now dare to live such a life that would take away the occasion for suicide and euthanasia? And if so, what might such a life look like? In an age that prizes autonomy and individualism above everything else, derides accountability, and worships self-sufficiency, creating such a life will be no easy task. But if Christ calls us to bear one another’s burdens, can we do anything less?

The hospitals of medieval Europe, in fact, were established as religious communities in which monks and nuns cared for the sick and the dying; the French called them hôtels-Dieu, or “hostels of God.” By the ninth century, Charlemagne had ordered cathedrals and monasteries to build their own hospital facilities, some of which survive to this day; the tradition has been carried on by the Catholic Church. Sadly, as medicine evolved into a largely scientific discipline, its original spiritual core, though no less needed today, has largely withered away. Thus people now die attached to machines and monitors that blink and beep, while family and friends, sequestered in plush conference rooms, wait to be called in “when it is all over.” Such is the irony of modern medicine: though aiming nobly to eliminate suffering, we have unwittingly abandoned the dying.

If we really want to take death back, we need to bring the dying back into our churches, and into our homes.

If we really want to take death back, we need to bring the dying back into our churches and into our homes. We need to push away those intrusions of medicine that pointlessly serve only to prolong the process of dying, even as we embrace those interventions that do relieve pain and breathlessness and nausea. We need to bring back priests and pastors and music, but most of all, we need to invite God back into the picture and put our trust in him, instead of in those new midwives of death, who, syringes in hand, promise a swift and painless dispatch into the unknown (and unaccompanied) night.

Margrit’s dying was not quick or easy, but as I look back on it now, I am certain that it was exactly as God intended it to be. She suffered, and yet bringing God back into the picture does not mean eliminating suffering; it means discovering and learning the only real way to bear it. Thus there was deep spiritual worth in our waiting for God’s moment; profound lessons learned from the mystery of not knowing, and of not being in control. We were helpless, and yet at the same time we were cushioned by unseen wings, and even as we grieved we could rejoice as hard hearts were softened, dull consciences stirred, and closed eyes opened.

The author with his wife Margrit in 2015

The author with his wife Margrit in 2015 Photograph courtesy of the author

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

The ancients believed we could learn something from the dying: that they were stretched between heaven and earth. To the extent that we ourselves resist the urge to meddle with divine timing, there is much we can learn from them still today. In the community where I live and work, almost no one dies in the hospital, much less the ICU. Most, like Margrit, die at home, in their own beds, surrounded by flowers and music and children and singing. They are very ordinary people, and they fear death and disability like anyone else, but the active love that surrounds them helps answer their fears, and the prayers of those who watch with them through long days and even longer nights uphold and strengthen them more powerfully than any carefully titrated medicine. They also do not die alone, and never need to organize their own wakes.

We cannot condemn those who, whether from fear of the future or due to the misery of their condition, decide to end their own lives, but we can point to another way. This is the way of hope in life beyond death and the way of meaning in and through suffering.

The apostle Matthew shows us this way when he describes the suffering of Christ: his very human reaction to it (he prayed for deliverance) and his ultimate obedience and bravery. Incredibly, when hanging on the cross, he refused vinegar mixed with gall, a mixture which historians tell us was supposed to numb the mind and thereby dull pain. He did this so that he could face death with a clear mind: proof that he was laying down his life for us, accepting suffering voluntarily.

In this way is his death an example to those of us who claim to follow him, and in this way will all of us, facing the inevitable pain and infirmity that is our lot, one day be faced with the same choice: to reject and avoid suffering, or to submit to it in God’s name – and with his grace allow ourselves to be purified and redeemed through it.

Already in the first century, the apostle Peter exhorted his readers to submit to the discipline of suffering, suggesting that it could serve a holy purpose: “Since therefore Christ suffered in the flesh, arm yourselves also with the same intention, for whoever has suffered in the flesh has finished with sin” (1 Pet. 4:1). Peter goes on to say, “But rejoice insofar as you are sharing Christ’s sufferings, so that you may also be glad and shout for joy when his glory is revealed” (1 Pet. 4:13). Paul similarly suggests that we should “boast in our sufferings, knowing that suffering produces endurance” (Rom. 5:3).

The writers of these New Testament passages may have been talking primarily about religious persecution, but, in the end, the subjugation of the body – and the spiritual purification with which we can be blessed as a result – need not depend on the source of our pain. An example of this is Alison Davis, who, as Robert Carle writes, survived a suicide attempt and whose newfound will to live exemplifies the possibility of finding a fruitful and fulfilled life, even when that life has been physically wrecked by pain and disability.

Born in England in 1955 with spina bifida and hydrocephalus, Davis was confined to a wheelchair by the age of fourteen; by thirty, having developed emphysema, osteoporosis, and arthritis as well, she attempted suicide. At first furious that she survived, she eventually went on to experience a conversion, a pilgrimage to Lourdes, and then twenty-eight years of service to the least and the lost, serving death row inmates in Texas and founding a charity for disabled children in India.

Dignity does not depend on autonomy or independence.

Such a life shows that dignity – a term much bandied about, but which comes from the Latin dignitas and means “virtue, worthiness, or honor” – does not depend on autonomy or independence, and certainly not on lack of suffering, but rather on our ability to accept the crosses laid on us in life, and to wait patiently for God’s hour when it comes to death.

None of us wants to suffer needlessly. But neither can we ever avoid pain and suffering completely. The very Son of God himself had to endure the bitter agony of the cross, and it was through this ordeal that the world was redeemed. Can we presume to escape with anything less? Alice von Hildebrand says that when we look at suffering in this way, it becomes a privilege: we suffer alongside the Savior. “Be faithful until death,” he urges us, “and I will give you the crown of life” (Rev. 2:10).

Absent a living faith, and without the surrounding love of an active community, it is entirely understandable that people want to take death back into their own hands. But as followers of Christ who have been charged with preaching the Good News to all people – who know that there is, to quote the apostle Paul, a “far better way” – we know that those hands are empty, and so we cannot stand silently by.

Reuben Zimmerman is a physician assistant who lives and works at Woodcrest, a Bruderhof in Rifton, New York.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

M Metzger

thank you...

Jane Herr

Notice no mention of dementia here. All your examples seem to be folks who have the ability to make their own decisions one way or the other. Seeing the fear and pain my father is suffering I am making my own plans for a way out before I succumb to a living death.