Subtotal: $

Checkout-

The Communion of Empty Hands

-

Poem: “Zeal”

-

Poem: “Winter”

-

Editors’ Picks: Demon Copperhead

-

Editors’ Picks: How to Inhabit Time

-

Editors’ Picks: Faith, Hope and Carnage

-

The Gift of Palliative Care

-

Transforming Food

-

On Planting Sugar Maples

-

Letters from Readers

-

Covering the Cover: Pain and Passion

-

Oberammergau’s Broken Vow

-

The Unutterable Silence of God

-

The Mind in Pain

-

In Search of Solace

-

Where Are the Churches in Canada’s Euthanasia Experiment?

-

Letters from a Vanishing Friend

-

The Dust on All the Faces

-

Two Thousand Years of Christian Strangeness

-

God’s Purpose in Your Pain

-

Saving Friends: What I’ve Learned from Insufferable Patients

-

The Speaking Tree

-

The Way of the Passion

-

Chinese Christians’ Costly Allegiance

-

Baptism Means Leaving Home to Find It

-

Felix Manz: The Making of a Young Radical

The Return of the Bison

In the Great Plains, scientists and small farmers bring back a mythic beast and a lost ecosystem.

By Nathan Beacom

March 10, 2023

The priest sat ready to receive the sacrament, and the chief, with a long wooden spoon, fed it to him. It was not the Eucharist, but bison meat. Father Jacques Marquette’s long Jesuit cloak was gathered about him on the Iowa soil. It was 1673, and he was the first European ever to come down the river. For the Peoria tribe of that time, feeding a visitor bison meat was indeed a sacred ritual – a sign of communion and welcome. This meeting was one of comity, though the encounters between European settlers and native people would, of course, be fraught and violent in the coming centuries. For now, with the sharing of bison meat and the calumet, there was friendship and peace. It was Father Marquette who first put down a description of the American bison in writing, calling it a “wild ox.”

As this anecdote suggests, the bison has traditionally held a special place in the spirituality of the native people who have shared its ranges over the centuries. The animal was historically a font of life, a rich resource, a self-sacrificial creature that gave its last bone and sinew for human use. Food, clothing, tools, threads, needles, tipis – all manner of essentials were crafted from the bison’s carcass. Later settlers also revered the bison, in their way: many civic buildings across the prairie states are adorned by bison as symbols of nobility and wisdom.

Harper Henry, Turquoise Traveler, oil on canvas, 2019. All artwork by Harper Henry used by permission.

The American bison stands at the crossroads of the animal, plant, and human worlds. It is part of an integrated ecosystem that includes people as much as it does bobcats, finches, and sunflowers. Finding the right way to relate to this, our national mammal, might show the way to a healthy relationship with the natural world of the American West.

It’s September, and the prairie is alive with the hum of pollinators. Yellow-flowered cup plants, wild bergamot, and asters dapple the hills in gold, purple, and white. The wind sends waves through the shoulder-high grass. I’m on an overlook at the Neal Smith National Wildlife Refuge outside of Prairie City, in Jasper County, Iowa. On the opposite hillside, a group of fuzzy brown balls are moving through the grass. These are the bison cows and calves. Much of the year, bulls are too rambunctious, and there is a strict separation between the sexes. This is the time for mothers to nourish and raise their young.

“I like seeing the mothers and calves, they’ll talk to each other. The mother will make her little noise, and the calf will answer,” says Karen Viste-Sparkman, the biologist on staff at the refuge.

“As you get to know them, you get to see they’re individuals,” she continues, recounting some favorite stories from her fifteen years tending this prairie and its animals. “There was one year that we had a cow that died after she had her calf. And I kept an eye on that one and kept in touch with the wildlife vet to know what we should do, how to tell if he wasn’t going to make it.” Meanwhile, the calf had taken matters into his own hooves by “going up to every adult bison, bulls included, and trying to nurse from them,” she laughs. “He ended up getting adopted by this yearling cow who had never had a calf of her own. It was just like mother and calf, and they would stick together.”

In the windswept remoteness of the prairie, huge sky overhead and interminable land all around, you meet face to face, the bison nodding and blinking slowly with its giant, thoughtful eyes, and there is no cloak of human civilization about you.

Another pair that touched her had the caretaking going in the other direction, with a young calf looking out for an older cow. The mother was three years old and went blind in one eye, and then the next year, blind in the other. She could no longer keep up with the herd on her own. But the calf ensured that his mother was never left behind, guiding and prompting her along.

This bison herd was brought here in 1996 to anchor the prairie restoration effort. Prior to settlement by Europeans, the state is thought to have been around 80 percent tallgrass prairie. Now, prairie is rare, with only 0.1 percent of the original prairie remaining.

In the 1920s, people began to notice that this landscape that once covered large regions of the American West had almost entirely disappeared. It clung only in the hard-to-farm places and along the railways. Aldo Leopold, the legendary conservationist, wrote in dismay in the 1940s about the future of the prairie and its largest resident: “What a thousand acres of Silphium [compass plant] looked like when they tickled the bellies of the buffalo is a question never again to be answered, and perhaps not even asked.” Incredibly, Leopold was wrong, and this points to the magnitude of the achievement of the Neal Smith refuge, for today, you may indeed see the buffalo wandering about thousands of acres of tallgrass prairie just south of Des Moines.

The bison were an integral part of this first-ever major project in prairie restoration. This is true in two major ways, Viste-Sparkman tells me. First, in terms of the health of the prairie itself: The bison is a prodigious grazer, happy to munch on the bunchy, dry grasses of the Great Plains that are low in nutrition and indigestible by many other animals, as well as the richer grasses of the prairie. Its grazing habits enrich the diversity of the prairie, dispersing seeds across the landscape from its coat and scat and clearing space for new plants to come up and access water. Bison wallows, the muddy, wet sloughs it digs in summer, make an important resource for birds and breeding ground for insects. Bringing back the prairie has meant bringing back other species too. Henslow’s sparrow, for instance, was almost nonexistent in Iowa before prairie restoration picked up in the 1990s.

Second, the bison is the finest ambassador for the grandeur of this ecosystem. “The bison are here for the benefit of the prairie, but they’re also here to educate,” says Viste-Sparkman. Beautiful as the environs are, what people often come for is to see the bison.

From my own experience, in the more remote stretches of South Dakota, the encounter with a bison is a striking thing. In the windswept remoteness of the prairie, huge sky overhead and interminable land all around, you meet face to face, the bison nodding and blinking slowly with its giant, thoughtful eyes, and there is no cloak of human civilization about you. And though the bison looks serene, if he should stand up and stamp, all the power of his massive frame becomes apparent.

The bison is enormous, its head larger than a man’s torso. Its hair is ten times thicker than domestic cattle’s, and that’s not including the thick woolly undercoat. The bison has the lowest critical temperature of any bovine species, putting the yaks of Mongolia and the long-haired cattle of the Scottish Highlands to shame, and is able to continue slowing its metabolic rate to survive efficiently at deep subzero temperatures. In these conditions, the bison body consumes energy at such a low rate that it can survive periods of intense cold and food deprivation. In the awful blizzards of the northern Great Plains, the bison settles face-first into the storm and trusts in the formidable insulation of its thick coat. But the bison is also fine in summer temperatures, and, before widespread settlement, once roamed much of the interior of the continent, save for the deserts and coastal regions. Happy on sunny hillsides grazing rich grass, the bison will also use its massive head to shovel away snow and find forage in deepest winter.

When it comes time for a rancher or a naturalist to work a herd of bison, the process is definitely a wilder one than with any domestic cattle. The bison panics if it is separated from the herd, and it will buck and run like mad. But even as the bison retains its wild nature under human management, it is wrong to imagine these animals existing in pristine, untouched wilderness prior to the arrival of European settlers: bison were always in relationship with the people who inhabited this continent. Native peoples were managing herds (culling, guiding, using prescribed burns to direct them) for many centuries before Marquette came down the river.

But it’s an old story how this balanced relationship was disrupted by Americans and Europeans coming west for economic opportunities: seeking gold, building railroads, revolutionizing agriculture. The “avarice of the white man,” as President Grant called it, meant that he was constantly making incursions on native lands, and this led to violence. Perhaps most famously, gold mining in the Black Hills led the United States to shirk its treaty obligations to the Lakota, which in turn led to the bloody conflict of Little Bighorn and what followed.

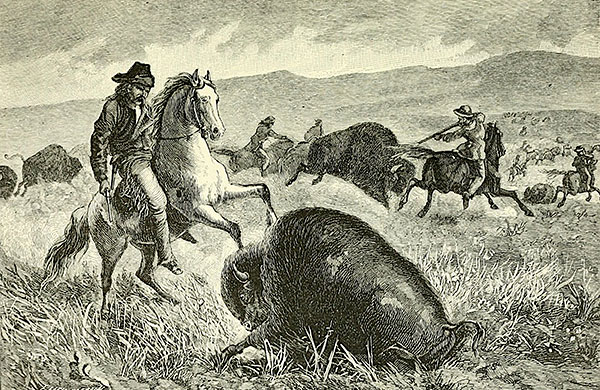

Illustration from the travel guidebook The Great Northwest by Henry Jacob Winser, 1883.

Leaders in the United States Army, like the legendary Civil War generals William T. Sherman and Philip Sheridan, undertook to clear away the American Indians from emerging American settlements and railway lines, confining them to designated reservations. But so long as the buffalo roamed across the west, native hunters would follow. Forcing out the American Indians, therefore, required clearing the bison so central to their way of life.

The Army encouraged hunters to travel west and bag as many buffalo as they could. At the time, it seemed as though the animals were endless. It is thought that their number in the American West exceeded thirty million. But a herd of buffalo out in the middle of the prairie was no match for hunters with long-distance rifles, and by the end of the nineteenth century, they were almost extinct. Private industry was even more responsible than the Army for this collapse. In the middle of the century there was a brisk trade in bison hides. So unlike native peoples, who used the whole buffalo, hasty hunters would skin the animal out on the plains and leave the carcass to rot. Hides flooded the market and the trade in bison eventually cratered, but not until the creature had been overhunted nearly to the point of no return. Even the cowboy William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, who purported to have killed more than four thousand bison in just eighteen months, was writing in dismay by the end of his life about the damage that he and hunters like him had done.

Ecologically, the loss of the bison coincided with the loss of the prairie. Humanly, it coincided with the near loss of native cultures and ways of life, contributing to generations of economic and social disadvantage for those growing up on Great Plains reservations. As the bison went, so went the West.

“To protect these animals, we have to use them. They have to have a purpose or they will go extinct,” Gail Griffin tells me, of the movement to raise bison for meat. “Buffalo go through the thread of this country for thousands of years, and if we don’t protect the species, we lose something.”

Thirty years ago, when Gail and her husband, David, moved into a rundown old farm, they never imagined it would become the business it is today, Rockie Hill Bison. “When we first got here, the place was basically unlivable,” Gail says from across her sturdy kitchen table. “When we drove in to look at the place I just told her ‘don’t look at the house,’” David laughs. He’s a big man in overalls and white goatee with a face that looks stern until a chuckle or a good story lights a twinkle in his eye. We’re on the eastern border of Minnesota, near the city of Winona, on those beautiful bluffs that line this stretch of country along the Mississippi. It’s February and sunny but well below zero. The cold, clear light sparkles off the snow, and, in the distance, bison huff soft clouds of steam, not looking the least bit cold.

Harper Henry, American Bison, oil on canvas, 2018

“You should’ve seen it. The basement was full of junk. We opened a shower curtain down there and it was just hundreds and hundreds of shampoo and detergent bottles and so much junk down there,” Gail says. David adds, “And the outside was just like that too. This guy had actually had people pay him to dump their junk in the ravines on the property, so there were just piles of old appliances, refrigerators, washer machines, other junk. Took about two months to make it livable inside.”

As the prior landowner had approached his own home and waterways, so also had he approached his soil, which was degraded and full of chemicals. “The person we bought it from farmed up and down the hills. Corn and beans. Nothing else. We put in strips and waterways and got it cleaned up.” Fortunately, David used to own an excavating company and had the machines to move all of the detritus from the land and start to bring it back to health. Without that, it would’ve been too expensive to rent those machines and get it cleaned up, the couple agrees.

Ultimately, restoring the health of this farmland was tied to putting bison back on it. But that wasn’t the original inspiration for getting the animals. “There was a guy who owned a concrete company in Winona. He came up to me one day and he said, ‘Every contractor has got to own some buffalo.’ I looked at him and said ‘Sure.’” David makes a skeptical face. “‘Why? You got some?’ And he said, ‘Yeah I won ’em off some guys in a game of poker in Iowa.’ He had them out by Highway 61 just north of town and said, ‘Come on, I’ll show you some.’ I looked at them and bought three calves right there.” Back in the 1990s, apparently, there was quite a boom in buffalo hobbyists. David was hooked, and just needed to convince Gail (who would go on to serve as president of the National Bison Association). Up to then, they’d been feeding young bull calves for David’s dad, but it was too time-consuming, whereas bison are low-maintenance. David and Gail only work their animals once a year.

Ultimately, restoring the health of this farmland was tied to putting bison back on it. But that wasn’t the original inspiration for getting the animals.

Over time their herd grew, and they had to develop what had been a nearly nonexistent market for their meat. Today, they send their animals for processing at a local plant and sell them to supermarkets and restaurants. They also sell to the local school system, and Gail, who has a background as a hospital nutritionist, teaches the school kids about healthy eating and local livestock agriculture. In the 1990s, though, wealthy people just wanted animals and had no plan for what to do with them. I ask the couple if bison ranching had been consistently growing since they started. The answer is yes and no. Around 2000, with all these growing hobby herds and inexperienced ranchers and no market built for meat, bison ownership crashed. Producers had to get serious about marketing their product and finding ways to get it out in front of people. “We were serving chicken at our own National Bison conferences,” remembers David. In the years since, the bison meat market has grown tremendously, and, with it, the number of herds of bison that roam hills much like these.

Bison are a fitting meat for our day, when consumers and producers alike are more aware of the ill effects for the environment and animal welfare of conventional livestock agriculture. Many customers also appreciate how nutritious and lean bison meat is. A typical meat cow is fattened on corn at a centralized feedlot before heading to one of the factories of the Big Four meat companies for slaughter, and a typical hog may spend nearly its whole life in an indoor pen. The concentrated animal waste these industrial farms produce is bad for waterways, and, with them, there is no longer the reciprocal ecological relationship between the animal, the plant life, and the soil. Bison, by contrast, roam free, feeding on a complex mix of native grasses.

At the same time, the ongoing existence of these animals, at least at scale, depends in part on their agricultural production. “You can’t afford to have them just because, or because they’re good for the environment,” Gail says. “You’ve got to promote the meat to promote the animal.”

Our teacher the bison shows us a way of relating to the natural world of which we are a part, a world where each part is connected and all things are held in balance.

Along the way, “it’s caused us to do a lot of research on what was here before, and we’ve added more than eighty-seven native plant species to our pasture now,” she continues. “We’ve spent time learning about what was on this land. We’ve become grass farmers who happen to harvest that grass with bison.” I ask the Griffins what inspired them to take a piece of land that was sick and spend nearly thirty years bringing it back to health. “It was a challenge,” David winks. “I’m kind of bullheaded.” In meeting this challenge, they have taken a piece of land with degraded soil, serious erosion, low diversity, and a heap of garbage and turned it into a flourishing ecosystem. With the bison and the grass back, the insects are back, the topsoil is returning, and the birds too. “When we first moved here, in 1993, Audubon came out and counted twenty-six bird species; they came back about ten years ago and counted ninety-seven,” Gail says. “We have sandhill cranes here now. All of a sudden you’ll see a new bird show up. Tanagers. I’d never seen a tanager, and over in our east woods there’s a fairly good population. So I get my small thrills here,” Gail laughs.

They are collaborating with their neighbors to restore the land. One landowner alone can’t control invasive species or chemical pollution. “It forces you to talk to each other, rather than just say, ‘ugh, look what they’re doing over there,’” Gail says. “We are known for working together and learning together.” The project is intergenerational: “Our grandson has been into bison since he was a little kid, and now he’s nineteen and wants to take up after his grandparents.” Gail looks ahead to what their efforts will have yielded fifty or a hundred years from now. “These will be things that will carry forward when we’re gone.”

Harper Henry, Good to Be King, oil on canvas, 2021

We step outside into the frigid Minnesota weather to look at the bulls. As we walk, some of them look away, and some square themselves at us and paw at the dirt. Even in the dead of winter, this hill country is beautiful, and I can see the trees Gail and David have planted lining the ridges and valleys. Looking into the big, obsidian eyes of a bull, I think on how it was a handful of bison calves that brought all this – this interconnected revival of animal, plant, and human community – about.

The Lakota say “Mitákuye Oyás’iŋ” – that we are all related, that the tallgrass and the buffalo are part of our extended family, and we of theirs. Human beings need not be foreigners in nature, unless we act wrongly. If we act as if the rest of the world were only raw material for our human desires, we corrupt and abuse natural balances and laws that we did not create and cannot really change. But if we treat the natural world’s own forms, patterns, and laws with respect – even when we are using it to support human needs – we might be relatives.

This is what the Griffins are doing, and what the Plains Indian reservations are doing with their revived bison herds. We can find ways to reap the resources we need from the land while also being its caretakers, keeping in mind the beauty and worth of a place beyond just its profitability.

Our teacher the bison shows us a way of relating to the natural world of which we are a part, a world where each part is connected and all things are held in balance. This ancient ambassador for our continent reminds us of our tie to, and responsibility for, the particular land on which we live. We need the bison, and the bison need us.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

burl self

Great article. A great book on this issue : Mari Sandoz's Buffalo Hunters. Theodore Roosevelt traveled West to hunt Buffalo as a young man. They were gone. He could not believe something that tragic could have happened. The experience contributed to his passion for conservation. Support Nature Conservancy's Tall Grass Prairie Reserve near Pawhuska Oklahoma and their 4000 + head Bison herd. Worth a visit.