Subtotal: $

Checkout

Rediscovering Pope John Paul II

Twenty years after his death, it’s a good time to take a fresh look at the legacy of a remarkable man.

By Nathan Beacom

April 2, 2025

Eleven years ago, I sat on the cobblestones of the Via della Conciliazione in Rome at midnight, playing cards and drinking scotch with Croatians and Koreans. We were in a throng of almost a million people waiting to attend the mass where John Paul II would be canonized. When he died in 2005, thousands shouted “Santo subito!” (Make him a saint!) around the Vatican. Now I could look around and see the diversity of the world church. There were Ghanaian women in fabulous traditional dresses made out of cloth featuring his face, Japanese men carrying his picture, Indian priests leading the rosary in Hindi, Mexicans carrying the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe. It was a living embodiment of his dream of human unity, and of the deep love so many around the globe held for him.

It’s hard to overstate the influence of this pope on world history, and, at his death and canonization, thousands of articles were written on his thought, life, and legacy.

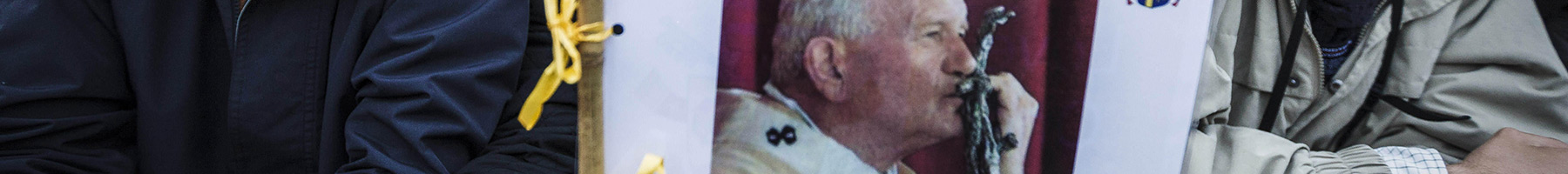

A woman holds a photo of Pope John Paul II during his canonization, Saint Peter's Square, Vatican City, April 27, 2014. Photograph by Giuseppe Ciccia/NurPhoto/ZUMAPRESS.com/Alamy Live News. Used by permission.

Twenty years ago, John Paul II’s name was everywhere in catechesis and Catholic education, and speakers seeking to interpret and spread his “Theology of the Body” to the masses were heard at Catholic conferences, retreats, and high schools. Some of those speakers are still active, but they have long since dropped any focus on “TOB” and “JPII.” The generation that once called themselves “JPII Catholics” are entering middle age, and the young – some of whom were not even born at the time of his death – no longer seem inspired by his example, perhaps because they were not exposed to it. There is a shrine and museum built to him in Washington, DC, but most days it is empty. The donors who constructed such things, who were so influenced by him, are themselves aging out.

Even before his passing, he was in a long, physical deterioration that allowed him to recede from view, unlike when he was storming around the globe and confronting dictators and consoling the world’s poor.

Twenty years later, it’s worth taking another glance at his legacy. How can we understand this figure who once loomed so large? Too often cast as a conservative by the wider world, and as a liberal by traditionalists, he wasn’t either. Driven by a higher purpose, his positions on political and moral issues fell outside of any right-left binary. At the root of these apparently disparate positions was a profound and consistent philosophy – a manner of thinking that has something to say to people of every denomination and faith.

What follows does not attempt to take on the whole of his biography and legacy, or indeed his frailties and failures, as all humans must have. He has, for example, been criticized for his handling of sexual abuse scandals in his church. But in tracing his footsteps to a series of stops around the world, I hope to rediscover in his thought something healing for our present age.

We Have No Right to Be Afraid

In the foothills of Mount Meeker, in Colorado, a local priest was leading a camping trip in the 1930s. Watching the stars at night, a meteor streaked by, and appeared to the hikers to have landed in the earth over a nearby hill. When they reached the spot, they found a large, flat-topped rock formation. The priest immediately thought of Christ’s words to Peter, “You are Peter, and upon this rock I shall build my church.” The priest made it his mission to construct a chapel on the top of this rock, and, still today, the Chapel on the Rock, a simple stone structure, sits in the peace of the valley. In 1993, John Paul II, a successor of Peter as head of the church, would visit this chapel, taking a break from his public appearances to do what he liked best: pray, read poetry, and climb mountains. I had the opportunity to follow his example, and enjoy the calm of those foothills some years ago.

It is an apt place to try to capture the essence of this man. The minty purity of the mountain air bespeaks that exuberant, confident simplicity with which he addressed the world. John Paul II was a man of great philosophical subtlety, which is why his scholarly writing remains impenetrable to most, but, as a public figure, he was as bracingly direct as a gust of wind. He spoke with a simplicity deeper than complexity. Before endeavoring to give moral instruction, this pope began by telling people an actual piece of good news: I know that you are afraid and anxious about many things, but you don’t need to be! You are worthy, you have dignity, and you are loved beyond all your imaginings.

John Paul II, like the Vatican II documents he helped to shape, sought to speak universally to humankind and to address himself to our fundamental needs and worries. In his inaugural homily, he sought to express this basic situation: “So often today man does not know what is within him, in the depths of his mind and heart. So often he is uncertain about the meaning of his life on this earth. He is assailed by doubt, a doubt which turns into despair.” The solution he gave was just as simple: “Do not be afraid. Christ knows ‘what is in man.’ He alone knows it.” What Christ knows is every human being’s “deep worth and dignity.”

In Los Angeles, John Paul II told an audience of journalists that they must remember to see everyone as lovable, both the subjects they report on and themselves: “All that I have said about human dignity applies to you. … You are more important than success, more valuable than any budget. … You are called to what is noble and lofty in the human being.” To young people on the Boston Common during his first visit to America, the pope expressed sympathy with their anxieties and an understanding that these fears can lead to damaging behaviors, but promised another way: “Today, I propose to you the option of love, which is the opposite of escape.”

How different this is from our current climate of fear! Those on the right have so often become suffocated by fear of the outside world, by worries that they are being targeted and attacked, by dismay at the moral state of the Western world. Some on the right have embraced the doctrine of Carl Schmitt, that we cannot have friends without having enemies. The left, too, is full of fear of “oppression” coming from the right.

John Paul II argued that Christian communication should never begin with contempt, but with esteem: “The missionary attitude is always one of deep esteem for what is in man, for religions, creeds, recognizing that the spirit blows where it will. The missionary spirit is never one of destruction.” The task of the Christian is to look for, and speak to, whatever is true, even if it is found outside the visible bounds of the church. “The Fathers of the Church rightly saw in the various religions, as it were, so many reflections of the one truth, ‘seeds of the Word,’ attesting that, though the routes taken may be different, there is but a single goal to which is directed the deepest aspiration of the human spirit as expressed in its quest for God and also in its quest, through its tending towards God, for the full dimension of its humanity, or in other words for the full meaning of human life.”

The church is not to take an embattled stance, but one, as he demonstrated, of joyful confidence. The church sees in human endeavors a “creative restlessness [that] beats and pulsates with what is most deeply human – the search for truth, the insatiable need for the good, hunger for freedom, nostalgia for the beautiful, and the voice of conscience. Seeking to see man as it were with ‘the eyes of Christ himself,’ the Church becomes more and more aware that she is the guardian of a great treasure, which she may not waste but must continually increase.” And this treasure is precisely the mystery of the divine dignity within the human person.

If we believe this is true, we can, without fear of losing the content, seriousness, or distinctiveness of faith, dialogue with those outside our own traditions with a sympathy for the human predicament and with the confidence that we have the great treasure of a truly good piece of news. Since this is so, we need not engage in what Thomas Merton called the “chatter” of controversy and politics until we have first understood and communicated the simplicity of God’s universal love for each and every member of the whole human family. John Paul II drew throngs of young people all over the world, precisely because he spoke a piece of news that was really good! In presenting the option of love, he was promising them a life of adventure and greatness, a life where things really matter.

The Great Adventure

One day, walking out of a church in the small town of Winterset, Iowa, an old farmer passed me. “See that man?” the pastor asked me, “He’s the guy that wrote the letter to the pope.” The story is a famous one in Iowa. Some forty years ago, Joe Hayes wrote a letter asking John Paul II to come visit, suggesting that it would be good for him to see a rural community, and to speak about care for the land. To everyone’s shock, the pope said yes. Not long after, the Holy Father was saying mass in the tiny, white clapboard country Church of Saint Patrick where Joe went to mass.

“Pope John Paul II, the spiritual leader of 700 million Christians, became a simple country pastor for a few minutes today in a little country church surrounded by the rolling green pastures and browning corn fields of Iowa,” reported the New York Times, “And his face glowed with the joy of the occasion.” One parishioner said, “He was just like a brother. It seemed like you knew him like you would your own brother.” In conversation with Hayes, the pope said “Ah, the farmer! We are all farmers.”

This more-than-a-pleasantry suggested something at the root of John Paul II’s philosophy. For him, life – especially the moral life – is a matter of self-cultivation, whereby we tend to ourselves like we would tend a garden. This philosophy, in the light of his deep devotion to Christ, would lead him to craft that great call to adventure, nobility, beauty, and growth in humanity that attracted so many millions.

Pope John Paul II in October 1980. Photograph from Creative Commons.

He wanted to better understand the story that makes up a human life. He began by looking at the smallest unit of a narrative, the actions performed by the characters. He believed that by examining the experience of action, we immediately perceive that two things reveal themselves: first, that our actions are free, and second, that they are transitive. The meaning of the first idea is pretty intuitive. The second idea, which sounds fancy, is also straightforward. By transitive, he just meant that the actions we take to change things in the world are just as much actions that change us.

These ideas lead to the idea of self-creation, or self-determination. We have the power to make ourselves into what we are. To the extent that we act fairly, courageously, mercifully, we will become fair, courageous, and merciful; to the extent that we act dishonestly or meanly, even in private, we will craft ourselves into dishonest, mean beings.

At the same time, he saw that self-creation was only possible on the basis of the self that we are already given. We are not blank slates; we are born with a certain nature, with a body, with relationships to people and to the world, and with relationships to the values of truth and goodness.

Self-determination can only occur when we are “self-possessed,” he argued. That is, we can only determine who we will become if we also possess ourselves, if we are in charge of our choices, rather than just determined by our feelings or desires. To be self-possessed is to be in command of one’s self for the sake of some good aim. Through self-possession, we can reach something bigger than ourselves, something that can give our life meaning.

The person who has failed to possess herself is no longer free, because she is owned by pleasures, drives, and desires, unable to say no to them, and therefore unable to freely say yes. This leads to a “disintegration,” where the human person, who is meant to be whole, becomes fractured. Our actions, our desires, and our conscience become untethered from one another, and we are subject to “inner tension” and anxiety because our conscience and desires are pulling in opposite directions, ripping us apart. Conscience is that voice which does not merely express our feelings and desires, but speaks to the truth, to something higher, to the “need for the good, the hunger for freedom, and nostalgia for the beautiful.”

To be integrated and self-possessed in this way is, he says, to really be “somebody,” that is to say, to be fully alive. This gives a meaningful path to the young, who long to be called on an adventure, to do something worthwhile, and to have something to strive for. Our fulfillment comes, not from gratifying our desires, but from striving to be great, to be free, to be good, to be loving.

John Paul II’s constant refrain of adventure and his emphasis on the great dignity and meaning of every person were based on the idea that this drama of self-cultivation in the service of others is the most meaningful thing in the world, and is accessible to anybody. The thirst for it is latent in each person, it only needs to be encouraged by humane structures of familial, political, social, economic, and spiritual life. At the same time, this means that the structures of society must always respect even the least of us as free and as capable of goodness.

Peace and Liberation

In the heart of Bogotá, Colombia’s capital, there is a green, flowering public park dedicated to Simon Bolivar, the man who led the revolution that brought independence to much of South America. On a given Sunday, old men in tweed sip espresso and play chess, little kids wheel around on bikes, teenagers lounge in the grass, and countless pigeons coo and waddle among them.

Several decades ago, life was less idyllic in Colombia’s great city. It was dominated by the legendary drug cartels, while communist rebels engaged in fierce battles against the government in the forests and jungles. In the midst of this tough period, Juan Pablo II said mass at Parque Simón Bolivar and delivered a homily on the themes of peace and liberation.

Calling himself a “pilgrim of peace,” the pope described what he understood to be the structure of peace in human life, starting with the human heart and ascending to the highest levels of societal conflict. For the Holy Father, peace begins at the most basic and intimate level: peace between nations, peoples, cultures, and families is “mediated by the pacified heart of man.”

From this personal peace comes familial peace. Parents are unable to pass on what they do not have – without a pacified heart, which is a loving heart, children will be subject to the same wild and unstable swings of desire and emotion that their parents experience. It is because the family is the place where human beings first learn how to be human that the pope was so zealous about promoting family life. It is in family where we first learn, or fail to learn, to forgive, to apologize, to work together for the common good, to serve and sacrifice for others. This fundamental school of being human shapes who we become in adulthood, and what we make of our neighborhoods, cities, countries, and, finally, the world. In light of this great significance, it is clear why the pope thought it was so important to promote the health of marriages and of family life.

“Latin America,” he said, “is a lover of peace,” aware that it is the condition of human progress, but also aware of the threats to it in violence, armament, poverty, hunger, and environmental destruction. In these areas of political and economic justice and peace, John Paul II’s message was that policy and social life should be organized toward the vision of the self-determined, free, creative, and happy human life for all members of society. This made him a near pacifist about global conflict, but it also inspired his thinking on economic life.

Because John Paul II’s philosophy put the human person at the center of moral enquiry, he affirmed in Laborem exercens and elsewhere that the worker “always has priority over capital.” This is because, ultimately, capital is instrumental, whereas humans are an end in themselves. Unlike the means of production, humans are free and capable of self-determination, self-possession, responsibility, and creativity. The second principle then, is that humans always take priority over mere things.

In economic life, this means that things should be organized in such a way that they are most humanizing and dignifying for the worker. Because of humans’ freedom and creativity, it is not respectful of their dignity for them to become mere cogs in an industrial or corporate machine. For this reason, the pope rejects both unfettered capitalism and Marxism, arguing that monopolies and big business are dangerous, whether privately or publicly owned. On the contrary, ownership should be dispersed among laborers where possible, as is the case in cooperatives or employee-owned businesses. This is a philosophy which believes in the creativity of the market while also seeking to ensure, through civil society and government, that it does not impinge on the freedom and dignity of workers.

Finally, this personalist view has implications for technology, which, John Paul II said, can rob us of our characteristically human activities, depriving us of meaningful work and satisfaction. The pope may have had in mind the replacement of artisans and craftsmen by machines, but today we face even greater risks in the form of digital technologies. John Paul II recognized that, if we turn too much of our human sphere of action over to machines, we could be reduced to a machine-like life ourselves.

John Paul II’s philosophy of peace and liberation sought to make political, economic, and technological life places of humanity and love. In the face of unjust economies, war, dehumanizing technology, environmental degradation, and family breakdown, John Paul II left the Colombian people with these words from scripture: “My peace I give you, my peace I leave you. … Let not your hearts be dismayed or troubled” (John 14:27).

Conservative and Liberal

In the Aula Magna of the Angelicum in Rome, I sat and listened to Fr. Wojciech Giertych discuss moral theology. Fr. Giertych was the Master of the Sacred Palace under John Paul II, tasked with reviewing the pope’s writings before they are published. This dusty, paint-chipped building with a citrus grove out back had hosted young theologians for centuries. Today, it holds a diverse global group of students: a priest from Tehran, a retired punk rocker from the United States, seminarians from Korea.

The young Karol Wojtyła, who would become Saint Pope John Paul II, once sat as a student in this very room. He would go on to become a bishop, and to participate in the Second Vatican Council, in which he was part of a group of reformers who wished to “throw open the windows of the church” to let in the wider world. He embraced liturgical reforms and advocated new forms of artistic expression, swapping out the grand old crozier of former popes for a simple steel crucifix. He transformed the church’s culture around sex, arguing that, far from being shameful, it can be seen in theological terms as an icon of the creative love of God. His removal of the prudish coverings of Michelangelo’s nudes was testament to this change. He was an ardent nature-lover and environmentalist. He embraced the world’s cultures and the dress and traditions of Indigenous peoples. He was a warrior for peace who stood against the American invasion of Iraq, along with many other conflicts, and pleaded, “Never again violence! No to war!” He was an advocate of criminal justice reform and the abolition of the death penalty. He rebuked the acquisitiveness of capitalism.

At the same time, he was faithful to the inheritance of Christian tradition in terms of timeless truths it upholds, no matter how popular they may be in a given country or at a given time. Consistent with his respect for the dignity of each and every human person, he advocated for all who were most vulnerable in our society: the sick, old, poor, weak, and small. He argued for the dignity of committed love in a culture that had made sex cheap, exploitative, and lacking in dignity. Being free from a traditionalist attachment to the old just because it is old, he was free to embrace all that he found good and beautiful and wise in the artistic and intellectual traditions passed down by our forebears.

For John Paul II, this combination of beliefs, which might variously be labeled liberal or conservative, expressed a higher unity. This higher unity was found in Christ himself, who revealed in a definitive and special way the glory and the possibility of humankind through the supreme act of love, and who revealed the divine potential in us. We may not agree with every position John Paul II took, but he is an example of how to think in terms above and outside of political binaries and ideologies.

What does all this amount to? You might think that a deceased pope has little to say to those outside the Catholic tradition. But in a time rife with fear, mistrust, and division, it might be useful to remember the hopeful message John Paul II presented. The basis of his writing and speaking was an enormous respect for the dignity of the human being. This was a respect that believed peace was possible and that we could see one another as deserving of love.

Some people today fear climate catastrophe. Others fear an AI apocalypse. Others experience a dismay at the chaos of political life. Some of us fear our neighbors. It is easy to forget that John Paul II lived under Nazism, Communism, and the threat of nuclear Armageddon; his was no cheery and complacent time. It is when there is most to be afraid of that we must not be afraid. It is when we are most mistrustful that we must learn to trust. It is when we are most at odds that we must believe in peace. It is in a time of ideology that we must strive to see things as they are. If anything, the messages of John Paul II are perhaps as apt in our own day than they were in the midst of the Cold War. We are tempted to fear, to retreat, to be defensive, to despair. Whether you are Christian or not, John Paul II would remind you: there is greatness in you. Seek it. And do not be afraid.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Stephen Hoy

Uniquely, his legacy is remembered and cherished via a rose that was named for him by Dr. Keith Zary. It is a beautiful white Hybrid Tea rose with an amazing fragrance and is loved by rose enthusiasts.