Subtotal: $

Checkout

Catherine Doherty, a friend and inspiration to Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton, founded Friendship House, a Catholic Worker–style house of hospitality to the homeless in Toronto, and later Madonna House, a more rural intentional Christian community and international Catholic lay apostolate, of which the writer is a member.

Faced with the turmoil of the 1960s – the Vietnam War, the nuclear arms race, and the use of dogs and clubs against civil rights activists – Catherine Doherty opted for the way of peace by reaching into the depths of Russian spirituality. From the ancient Christian East, Doherty retrieved for the modern West a paradigm of peace. After much anguish and many sleepless nights on her knees before God, Doherty’s answer to our idolatrous society clouded by violence came to her from her own past: the poustinia.

Poustinia is the Russian word for desert, and a poustinik is someone who dwells there, in the aridity of the desert. Though dwelling in the desert has its literal aspects from ancient tradition, Doherty, who introduced the notion of the poustinia to North America, refers primarily to a spiritual reality. It’s an ethos to which she calls everyone – not just those few who end up living in the solitude of a cabin in the wilderness.

In 1962, Doherty hailed Thomas Merton as “a voice in the wilderness” crying out “against atomic warfare and for peace amongst men.” Indeed, “one cannot pick up a Catholic magazine or paper,” Doherty observed, “without reading his passionate plea.” Doherty likewise celebrated Dorothy Day for having “raised her voice for years … against war … and for the peace of the Lord.” Both Day and Merton, in Doherty’s estimation, were “writing so vividly, so convincingly, and so fearlessly” on behalf of peace. Seeing her two friends play this role as public prophets, Doherty cried out to God, from a soul “enveloped in a great darkness.” She groaned before the Lord, asking what he wanted her to do in the face of the destructive violence of modern warfare:

Every Christian must do more – with vows or without vows – wherever they are, whoever they may be! For ours is a tragic century where men are faced with tremendous decisions that shake the souls of the strongest. This is also the age of neuroses, of anxiety, of fears, of psychotherapy, tranquilizers, euphoriants – all symbols of man’s desire to escape from reality, responsibility, and decision-making. This is the age of idol-worship of status, wealth, and power. These idols dominate the landscape like idols of old: they are squatty and fat. The First Commandment once again lies broken in the dust. The clouds of war, dark and foreboding – an incredible war of annihilation and utter destruction – come nearer. Dirge-like symphonies surround us and will not let us be.

Catherine Doherty, born Ekaterina Fyodorovna Kolyschkine in 1896, had only to reach back to her own childhood to retrieve for us the figure of the poustinik. From time to time, she and her mother visited a real-life poustinik themselves. “I got to be very familiar with one poustinik to whom my mother went for advice,” Doherty recounts. “We used to go there on foot and return on foot. When we arrived my mother knocked on the door and opened it. There was no latch on the door. The poustinik was always there to welcome anyone who came.”

Catherine Doherty

The Eastern poustinik is, on one level, simply “someone in a secluded spot.” Doherty explains that “a poustinik could be anyone – a peasant, a duke, a member of the middle class, learned or unlearned, or anyone in between. It was considered a definite vocation, a call from God to go into the ‘desert’ to pray to God for one’s sins and the sins of the world.” A member of any sector of society could suddenly disappear from their previous life in response to the divine call, and live in a new anonymity and solitude.

Doherty never names the poustinik who lived close to her Russian village. But the individual identity of the poustinik was not Doherty’s point. The point is the ethos of the poustinik, the mode of being which the poustinik models for us, not against society or apart from society, but for society and with society. The poustinik opts for the poustinia not as though it were a bomb shelter (preserving his own personal peace and security while the rest of the world goes to hell) but because the gift of peace given in his encounter with the Word of God is a gift not for himself. It is a gift poured forth upon the world.

The poustinik Doherty knew as a little girl was the inheritor of a long-standing charismatic tradition in Russia, which in turn had roots more ancient still. Doherty explains that the desert to which the word poustinia refers (in the context of the charism of the Russian poustinik) is the desert of the Desert Fathers. A poustinia is comparable to “a place to which a hermit goes and hence it could be called a hermitage.” To a Russian, poustinia “can mean a quiet, lonely place that people wish to enter to find God. It can also mean truly isolated places to which specially called people go as hermits to seek God in solitude, silence, and prayer for the rest of their lives.”

According to Doherty, the Russian poustinik was set apart from the world for the sake of the world, on behalf of the world, and for love of the world. The poustinik did not go into the desert to escape, reject, or spite the world. Far from living in isolation from the world, the poustinik felt the world’s pain and suffering; he felt the consequences of the world’s violence and carried those consequences – those wounds – in the depths of his own heart. As a positive alternative to violence, the poustinik – without escaping or hiding from the wounds of a violence-ridden society – existed in his poustinia to “thank God for the joys and gladness and all his gifts.”

Photo by Joanne Slugocki

Just sixteen years before Doherty’s birth in Russia, Fyodor Dostoevsky published his last great novel, The Brothers Karamazov. At its moral center is the character Father Zosima, a spiritual elder who carries the world’s wounds in his own heart. His capacity as a poustinik to bear the world’s wounds is coupled with an expansive heart of gratitude, undergirded by a prevailing vision of peace. Father Zosima, very much in conformity with Doherty’s description of the poustinik, counsels his disciples to ask “forgiveness of the birds” on the basis that “all is like an ocean, all flows and connects; touch it in one place and it echoes at the other end of the world.”

This mystical vision of creation animates the poustinik’s embrace of peace over and against violence. According to Father Zosima, a mere touch – if lacking in graciousness – can do violence across the globe, a violence for which the poustinik’s heart, “tormented by universal love,” cannot but ask forgiveness. This sense of responsibility is all-inclusive. “There is only one salvation for you,” Father Zosima exhorts his disciples. “Make yourself responsible for all the sins of men. For indeed it is so, my friend.”

Doherty assumed this sensibility as her own. She claimed responsibility for the Bolshevik-led armed insurrection in 1917, insisting “I started the Russian Revolution!” And she felt she held some responsibility for the death of Martin Luther King, Jr. In this spirit, the poustinik perceives that she is part of humanity’s sinfulness, responsible for humanity’s violence. The way forward, for the poustinik, is not in fleeing from or disowning the world’s sinfulness and violence, but in claiming it as her own.

But the poustinik is not simply the Eastern equivalent of the Western hermit. Doherty insisted we shed any connotations of escapism and retreat easily associated with the term “hermit.” The essential positive content of the poustinik’s vocation is far from a vision of rejecting society and human contact. By contrast, he is available, at the world’s disposal. Doherty recounts visiting the poustinik of her childhood, “There was a gracious hospitality about him, as if he were never disturbed by anyone who came to visit him. On the contrary, his was a welcoming face. His eyes seemed to sparkle with joy at receiving a guest. He seemed to be a listening person.” The world’s heartbeats were not distant from the poustinik’s own. His heart listened with as much loving concern to the cries of society as to the Word of God.

The poustinik does not exist in a vacuum. In 1962 Doherty asked, “How can we talk about peace before we talk about love? About caritas – of which peace is the fruit? It seems to me that we cannot have the fruit before we have the tree!” Foundational for raising our voices on behalf of peace and against atomic warfare is the conviction that peace is rooted in love. And it is this love that the poustinik contemplates, is formed by, and shares from his poustinia.

Poustinia stands for prayer, penance, mortification, solitude, silence, offered in the spirit of love, atonement, and reparation to God! The spirit of the prophets of old! Intercession before God for my fellowmen, my brothers in Christ, whom I love so passionately in him and for him.

Yes, that ‘doing something more’ can be the poustinia, an entry into the desert, a lonely place, a silent place, where one can lift the two arms of prayer and penance to God in atonement, intercession, reparation for one’s sins and those of one’s brothers. Poustinia is the place where we can go in order to gather courage to speak the words of truth, remembering that truth is God, and that we proclaim the word of God. The poustinia will cleanse us and prepare us to do so, like the burning coal the angel placed on the lips of the prophet.

The poustinik option, according to Doherty, is available to everyone – in the silence of walking down a city street or waiting for a taxi, or amidst the chaos of a day at work. Doherty asked, “What is the answer to all these darknesses that press so heavily on us? What are the answers to all these fears that make darkness at noon? What is the answer to the loneliness of men without God? What is the answer to the hatred of man toward God? I think I have one answer.” And that one answer? “The poustinia.”

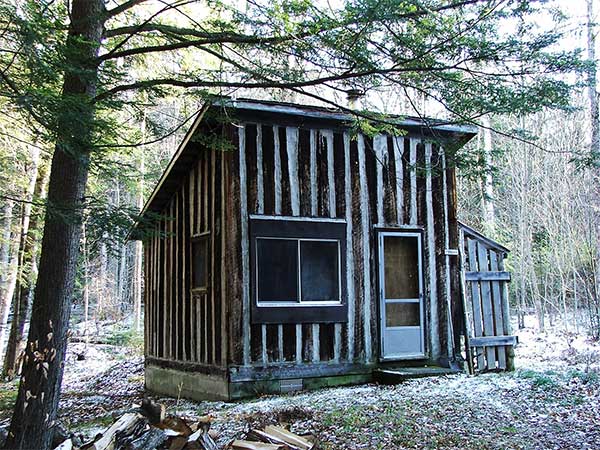

Catherine Doherty’s vision in advocating the notion of poustinia in North America came out of her experience at Madonna House, the Christian community of laypeople she founded with her husband, Eddie Doherty, in 1947. Within the boundaries of the community are remote cabins – poustinia – available for those ready and willing to disappear from their previous life in response to the divine call.

When I arrived at Madonna House in rural Ontario five years ago, I was keenly aware of the violence in the world at large and within my own heart. I periodically went to the poustinia cabins. I spent the day fasting on bread and water, taking walks through the bush, and chewing on Scripture – the sole object of “study.” Days of anonymity and solitude also led to wrestling with the violent inclinations of my own heart.

After eleven months at Madonna House, I headed to Washington, DC, where I lived at the Catholic Worker house. From there I participated in the weekly peace vigil in front of the White House and the Pentagon. But I returned often to the poustinia rooms available at Madonna House’s Washington community. There, for twenty-four hours, I quenched my thirst, drinking deeply from the poustinia source. Out of this lonely, silent place I received peace to stand in front of the Pentagon and the White House. In choosing the poustinik option, I kept vigil not only in front of the Pentagon but also over the five-sided, war-making machine within my own chest. In poustinia, I found courage to speak words of truth.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Student

Most Soulful and profound article I have read in years. Deep Dive. Keep digging deep, speaking in earnest. This writing of yours has impacted me in a beautiful way. Thank you. Exactly what I needed.

Christine Kuepfer

I know it wasn't the main point of the article but I got stuck at the part where I have to accept and take responsibility for the evils of the world. I know that both guilt and community are an intrinsic part of Mennonite culture (sarcasm) but I'm struggling to see the theological underpinning of that philosophy.

Alliee DeArmond

Catherine's book, "Poustinia" was very helpful to me when founding The Word Shop, a volunteer driven used bookstore in Aptos, CA. At a time when wandering by most churches on a given week-day, one would only find a locked and deserted building, it seemed important to me to create holy-spaces in the market place. The Word Shop created a small ever shifting community for 23 years, a conversational bridge between individuals and multiple denominations.