Subtotal: $

Checkout-

The Disability Ratings Game

-

The Way Home

-

The Beginning of Understanding

-

Time for a Story

-

The Island of Misfit Toys

-

A More Christian Approach to Mental Health Challenges

-

Made Perfect

-

Mary’s Song

-

The Art of Disability Parenting

-

When Merit Drives Out Grace

-

Hide and Seek with Providence

-

Unfinished Revolution

-

Falling Down

-

The Hidden Costs of Prenatal Screening

-

The Baby We Kept

-

The World Turned Right-Side Up

-

The Lion’s Mouth

-

How Funerals Differ

-

One Star above All Stars

-

Stranger in a Strange Land

-

Spaces for Every Body

-

Poem: “Consider the Shiver”

-

Poem: “No Omen but Awe”

-

Poem: “So Trued to a Roar”

-

Letters from Readers

-

Editors’ Picks: Dirty Work

-

Editors’ Picks: Millennial Nuns

-

Editors’ Picks: Directorate S

-

Letter from Brazil

-

Peace for Korea

-

Flannery O’Connor

-

Covering the Cover: Made Perfect

In some households it’s customary to invite relatives or friends for dinner mostly as a pretext for the moment the host says, “I wonder if we might play a game.” What no one says is that the socializing that precedes this invitation is also a game. Adults are allowed to ask the children questions like “What are you taking for your exams?” or “What do you think you’d like to be when you grow up?” That’s within the rules. But children are not allowed to ask adults questions back, like “Isn’t it about time you faced the fact that you drink too much?” or “How long do you seriously think that obviously fragile marriage of yours is going to last?” Those who long to play games after dinner are often those who prefer a game that calls itself a game to a game that doesn’t.

There are a lot of failed actors out there, and many households enjoy acting games, like Adverbs or Charades. But one game that’s more difficult than almost any conventional acting game is Questions. Questions appears in Tom Stoppard’s 1966 play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, which follows the exploits of two minor characters in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. In Stoppard’s play, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern pass the time by playing Questions. Their dialogue is a dazzling to-and-fro of catching each other out. It’s like verbal tennis, except every utterance must be a question. If you hesitate, change the subject, or say something that isn’t a question, you lose a point. You also lose a point if you ask an existential question, (“What is life?”) or a rhetorical question (“How long must I endure this tiresome game?”), or a question that largely repeats a previous one. There’s an elaborate scoring system in which three points make a game and three games make a match.

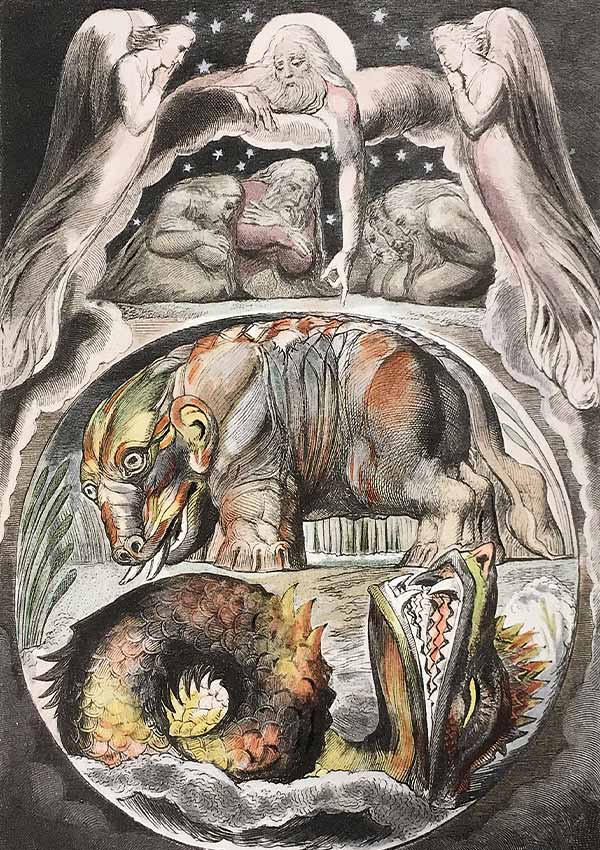

William Blake, Job Rebuked by His Friends, 1821

When it’s played well, as by Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, it’s amazing to watch, because players need both to suspend the desire to say something that isn’t a question, and to keep up with the rapid-fire exchange of counterquestions. So:

Why did you come to church today?

What would you have me do instead?

What are your favorite things to do on Sundays?

What would you recommend?

What did you like doing when you were a child?

What does childhood have to do with adult life?

Why don’t you like to think about difficult things?

Would you like me only to enjoy the things you enjoy?

Then the interchange might stop because the last question could be accused of being existential, rhetorical, changing the subject, or all three. But keeping going for eight questions is pretty rare.

The serious issue behind the apparently trivial game is this: Is answering a question with another question simply an evasion of any genuine dialogue, even to the point of hostility and exasperation – or could it instead be a joint entry into a deep mystery? Imagine a slightly different way of playing: Take away the penalty for hesitation, and give each other all the time that’s needed. Then keep the playfulness, but take away the element of competition. Then take away the cleverness, and turn it into a project of each asking a deeper question on the same trajectory as the previous one. Now you’ve turned an idle party game into a conversation you may remember for the rest of your life.

You’ve also gone to the heart of the book of Job. Job loses everything, and what he doesn’t know is that the reader is waiting to see if he will curse God. Job’s friends assume the issue is a moral one, and that Job’s losses are a result of his having done something wrong. But eventually Job dismisses them, and realizes his dispute is with God alone. Job rails against God, reeling off a list of quite reasonable questions that he demands God answer. In chapters 38 and 39, God begins to respond. But God’s response is not what we’re anticipating. There isn’t a big reveal that explains why things have turned out so badly for Job. Instead, God unfurls an overwhelming list of questions.

William Blake, God Answers Job from the Whirlwind, ca. 1804

God’s long speech covers twenty areas of the natural world and, in each case, God asks whether Job is capable of comprehending or conceiving of the ways of natural creatures or phenomena. The speech covers earth, sea, morning, the underworld, light, snow, storm, rain, stars, clouds, lions, ravens, ibexes, wild asses, oxen, ostriches, horses, hawks, and falcons. The effect is twofold: Job finds himself no longer furious but awestruck, humbled by his tiny place in a colossal universe of immense complexity and deft design. Meanwhile his situation is transformed from a problem into a mystery. A problem is a straightforward deficit like a breakage or a malfunction that you can simply fix and return to how it should be; a mystery is something unique and wondrous, which absorbs the whole of your intellect, emotion, aptitude, and experience – you can only enter, after which your heart and soul will never be the same again. Before God’s speech in chapters 38 and 39, Job is saying “Why won’t you fix this problem?” Afterward Job is saying, “Take me with you into this mystery.”

Over the last ten years, our community has hosted an annual conference on theology and disability. Participants in the conferences, several hundred people in total, come from extraordinarily diverse backgrounds, and have lived experience of a wide range of disability. Disabled people are invariably isolated by experience or geography – likely to be the only voice-hearer, wheelchair-user, deaf or autistic person within the local church and community. And otherness is exhausting. Disabled people face barriers that are invisible to other people, and find strength by finding each other. The events we convene prioritize the voices and experience of disabled people. This is not to be exclusive, but to provide a safe space. So much of the time the voices heard on disability – particularly in the church – are non-disabled people who speak from study or research or observation or living alongside someone. Theirs is good and important work, but somehow it has become the dominating voice – the theologians with family members or professional experience bring the lens of their theological training to the experience of those they live with. It is hugely valuable, but not the same. There are insights to be gained and huge amounts to be understood, but it is from the center looking out, rather than from the edge. Researchers living in a poor community report in, but with the knowledge of a salary and a bank account: it will always be observational. If it is the only voice, it can do damage. There is a power that comes with being listened to, being heard. But that can only ever happen when we are willing to speak, and if we have the opportunity, the tools, and resources.

Job finds himself no longer furious but awestruck, humbled by his tiny place in a colossal universe. His situation is transformed from a problem into a mystery.

Across so much diversity, participants have two things in common. They have experience and gifts that church and society have seldom understood, rarely honored, and frequently suppressed. And they have questions that challenge the location from which theology has often been approached and the subjects theology conventionally addresses. In other words, they’re looking for receptivity and belonging in church and society, and they’re drawing us all into deeper relationship with God. These two commonalities crystallize in the phrase “calling from the edge.” The edge of a forest is a very particular habitat, a precise place rather than merely not-center or not-outside. Things that struggle in the center, fail to thrive through lack of space or light, flourish on the edge. And things that struggle in open ground find shelter and shade on the edge. Disability too is a particular habitat. To be on the edge of church or society is not just to be looking inward at where we are not, but to be looking outward at what is beyond and looking around to see who else is there with us. There is a freedom on the edge, a space to grow in different ways, to find shelter and shade, space and light, to learn a different kind of flourishing.

We marked five years of this work with a booklet, “Calling from the Edge”; the tenth conference, in October this year, was “(Still) Calling from the Edge.” It’s worth reflecting on three possible meanings of the phrase. One is to say, “Hello, look over here, will you, there’s some of us on the edge, neglected, sometimes scorned, and invariably forgotten by everyone else.” One weekend a year our community turns everyone’s attention to a group of people who have a lot to say and whose wisdom and perspective is too often excluded. That’s the first meaning, and it’s not untrue, but it’s far from the whole truth of what the phrase can mean.

It’s also the case that anyone who sings the Magnificat, which speaks of God in Christ exalting the humble and meek; anyone who reads Matthew 25:31, which talks of meeting Christ in those experiencing disadvantage; anyone who reads the Beatitudes, which say “Blessed are you who mourn”; and anyone who knows the story of St Martin, who gave his cloak to a desperate man later revealed to be Christ – all of them know that the edge, rather than the center, is where the kingdom of God is to be found. So calling from the edge is calling for a renewal of church and society to be reshaped along kingdom lines, a call to turn the world upside-down – and those who are on the edge already are calling others to join them.

That’s getting closer to the truth. But “calling” is literally another word for “vocation.” What calling from the edge means above all is the discovery that those who live with disability have a particular vocation, and only when they get together, and only when the questions they are asking take center stage, and only when they are seen for what they uniquely are – precious, honored, and loved in God’s sight – and not for what they are judged not to be, can that true vocation, by which God is renewing the earth and inaugurating the kingdom, be discovered and embodied and lived out as a blessing. For each of us discovers our vocation when, often with the help of others, we reflect on who we uniquely are, what we alone have experienced, and how wondrously we’re made, and discover what we can be and do and say that only we can be and do and say. And the catch is that God has chosen not to bring the kingdom without us but through us – so if the kingdom is to be all God calls it to be, we must respond, and play our role in realizing it on earth as in heaven.

William Blake, Behemoth and Leviathan, 1821

Perhaps every disabled person has experienced others regarding them as “that annoying person who keeps asking us to change things or needing us to adapt so they can participate or belong.” In other words, almost every person with a disability is accustomed to being seen as one who asks questions that invite others to live in a bigger, more complex, but more wonderful world. Which brings us back to chapters 38 and 39 of Job. What we discover there is that the one who asks such questions is God. God is so annoying. God keeps calling from the edge, to say, “Is your world, is your church, big enough and complex enough to accommodate me? Only if you listen to my questions and allow yourself to be humbled and inspired by the universe my questions point to will your life be as wondrous as I made it to be.”

And that brings us back to the game of Questions, and the transformation in the way we play it. This is a challenge for everyone, those with named disabilities and those with hidden, unnamed ones. Are the questions disability asks about God going to be like Rosencrantz-and-Guildenstern questions: combative, annoying, impossible to stay with because someone always loses patience or can’t respond? Or are we going to allow ourselves to be drawn into a rather slower, less abrasive, more absorbing shared pondering, where each contribution invites a further question, more profound, far-reaching and awe-inspiring than the one before? Job had a sequence of quite legitimate, entirely appropriate, and very urgent questions. Yet in return, God gave him not answers, not solutions, but a torrent of further questions. Those questions were not defensive, not evasive, not hesitant. They were expansive, humbling, and inspiring. They led Job to transformation, wonder, and worship. They do the same to us.

Fiona MacMillan is a disability advocate, practitioner, speaker and writer. She chairs the Disability Advisory Group at St Martin-in-the-Fields, central London.

Samuel Wells is an English priest of the Church of England. Since 2012, he has been the vicar of St Martin-in-the-Fields in central London, and Visiting Professor of Christian Ethics at King’s College London.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Susie Colby

Calling from the Edge, in its various meanings, is also relevant for bereaved people. Job is bereaved. Perhaps his issue may be transformed from problem to mystery, but I would argue his issue was never truly a problem, but a tragedy - he has lost those whom he loves and among whom his place in the world is meaningful. His tragedy finds a place within mystery, but that is still less satisfying than here portrayed.

Tonya

Every word of this was so well written and thought provoking, but the sentence that knocked the wind out of me was: “And otherness is exhausting.” It made me understand my adult children’s disabilities and life better.

Susan Elizabeth Henson

Thank you for this magnificent piece on disability, the Church, and God's place in it all! As a disabled person, I appreciate you approaching this topic with such sensitivity and understanding.

elizabeth claman

Ive been disabled for the past 16 years after a stroke left me half paralyzed and changed my very active and dynamic life into something far smaller and more limited. I’m still in some ways deeply saddened by that transformation; however I’ve also come to accept it as a gift of sorts. Most notably it has radically enhanced my compassion, patience and gratitude for simple blessings.