Subtotal: $

Checkout

In Defense of Democratic Capitalism

A reader critiques Plough’s Summer 2023 issue on money.

By Larry A. Smith

August 19, 2024

In its Money issue (Summer 2023), Plough made a thoughtful and ethical case for common ownership of property. The authors missed something, however, as I will demonstrate through the work of Michael Novak, the philosopher-theologian who defined “democratic capitalism”. The two systems, capitalism and the Bruderhof’s model of Christian socialism, can complement one another and together enable women and men to flourish holistically. I conclude with a challenge for fellow Plough readers and admirers of the Bruderhof: to distinguish that which is a community’s gift to the church from that which the Bible prescribes for the entire church, and to encourage all the gifts.

Perspective: Common Ownership, from Money

Three authors presented a strong case for common ownership. Eberhard Arnold, founder of the Bruderhof, in “The Religion of Mammon” (1923) opens with Jesus’ declaration, “you cannot serve God and Mammon” (Matt. 6:24). Arnold argues: “Mammon kills; its very nature is murder. It is through the spirit of Mammon that wars have broken out and impurity has become an object of commerce.” Mammon is the cause of everyday injustice, it ”drives hungry children and the unemployed into villages seeking food, only to be chased.” Moreover, “capitalistic society can only be maintained by large-scale deception,” and “it is impossible to amass such a degree of wealth – which at the same time means power – without cheating, depriving, hurting, and even killing one’s fellow human beings.” Arnold concludes his diagnosis with “money and love are mutually exclusive.”

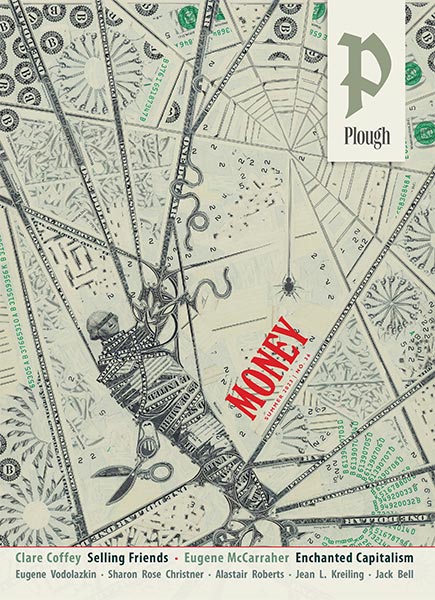

Eugene McCarraher, in his “Enchanted Capitalism” interview, focuses on the economic system, contending that capitalism is “very fragile,” in “terminal decline,” that “it’s almost dead, but thanks to all kinds of state support, the damn thing never quite dies.” In his view, advertising invites viewers to enter a faulty “moral universe” that does not justly assess need and value, so allocates resources inequitably. Capitalism is effectively idolatrous, distinguishing not only between “what is right and wrong, but what is real and unreal” based on economic value. McCarraher views the example of the community holding all things in common as normative, a prescriptive “small-c communism.”

Peter Mommsen’s “The Other Side of the Needle’s Eye” is less polemical as he lionizes an exceptionally wealthy fifth-century Roman couple, Melania and Pinianus, who gave away their vast inherited wealth in the hope of caring for others and having “treasure in heaven” (Luke 18:23). They succeeded in distributing all their riches but it was messy, “somewhat at random,” caring for various needs but also enriching other families of their class through bargain disposals. Eventually, the two retired to religious communities in Jerusalem and died without possessions. From this story, Mommsen challenges preachers to encourage Christians to follow the example of the early church, to renounce possessions. Mommsen invokes Tolstoy: “Poverty comes from man’s injustice to his fellow man.”

Nearby articles feature the Bruderhof and communities that share ownership.

In sum, from these three articles and related experience, mammon is associated with money and wealth as the source of much that is evil. Capitalism, with success measured by money and leading to wealth, runs contrary to biblical prescriptions and leads to various forms of inequity, suffering, and injustice – even idolatry. All this could be corrected through common ownership and allocation of goods based on real needs. Doing so would encourage virtue and thereby improve the lives of individuals and communities.

Elsewhere, people who favor shared ownership over capitalism generally have argued that socialism:

- Encourages equitable power sharing, avoiding a system in which those with the most money, individuals and large corporations, have excessive influence.

- Leads to balanced consumption, whereas capitalism, driven by advertising and consumerism, depletes the environment as we consume beyond our means.

- Inspires community virtues and mutual concern, while capitalism is associated with individualism and self-centeredness.

- Resolves wealth-based divisions, reducing a growing gap between rich and poor, domestically and internationally.

- Cultivates refined tastes, guided by intellectuals and artists, whereas capitalism leads to tasteless consumption and vulgarity.

Given the state of intellectual life in universities and the qualities of much modern art, I wonder about the final point. But the first four are supported by thoughtful advocates, demonstrably concerned for their neighbors.

Among the religious, scripture is employed to support socialism, including the redistribution of Jubilee (Lev. 25), prohibition of usury (Exod. 22), and common ownership in the early church in Jerusalem (Acts 2, 4). Various church proclamations – especially Roman Catholic but also Protestant – support all these points in the hope of creating equitable and peaceful communities.

We witness such a community in our Italian town where we worship with Capuchins, followers of Francis of Assisi who closely adhere to his original rule, including no ownership. Although we are not Roman Catholic, we have been welcomed and have gotten to know the local brothers, to learn from them, and to love and intercede for each other. As it relates to economics, the Bruderhof is an evangelical version and I deeply admire and am grateful for both communities.

Another Perspective: Democratic Capitalism

When I studied economics, we began with theory. Textbooks defined “capitalism” – ironically, a term that originates with Karl Marx – as an economic system based on private ownership of the means of production and its operation for profit. It was contrasted with “socialism,” characterized by common ownership with guidance of the means of production and distribution of goods by a political or social authority. We then explored issues related to the systems.

Michael Novak, in his highly influential Spirit of Democratic Capitalism, began with observation rather than theory. The obvious success of the American social-political-economic system persuaded him to abandon his socialist leanings in favor of a system that is: a) predominantly market-driven, b) within a polity that respects life and liberty, and c) enabled by cultural institutions that hold to ideals of liberty and justice. The system is possible because the economic-directive power of the state has been limited. Individuals and groups are thereby freed to pursue diverse economic objectives. When Novak wrote, this described the USA and very different models in Canada, countries in Western Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan. To designate the system, he coined “democratic capitalism.”

In support, Novak contrasts the performance of various economic systems, perhaps most tellingly those of Northern with Latin America. Adam Smith, the famous eighteenth-century economist-philosopher, had referred to the contrasting New World systems as an experiment, testing a Latin American system based on European guidance with the new ideas of the North. In Smith’s day, Latin America was advantaged in precious metals and other resources and, due to milder weather, in agriculture. Each region was dominated by European powers, which also provided nearly all their trade. Why then, Novak asks, has the Northern economy so consistently out-performed Latin America? With reason, he attributes Northern success to the then-new idea of democratic capitalism.

Money, in fact, presents consistent observations from Cuba (Harvey Maltese, “The Last of the Revolutionaries”), contrasting views by still-convinced veterans of the revolution with those of frustrated young people. Veterans remember Batista’s oppression and the benefits of asset redistribution after the corrupt regime was deposed. There has been little subsequent growth, however. One-hundred miles away Floridians flourish economically while in Cuba, as twenty-five-year-old Luis reports: “I have only ever known blackouts, unemployment, bad transportation.”

Novak summarizes other contrasts that support the inherent productivity of democratic capitalism, and he is not alone. For example, it is widely known that European economies – also living standards and life expectancy – were stagnant for centuries until roughly 1800, when steady growth enabled by new thinking began in Britain and America. And today, development economists generally agree that market development, not foreign aid, has been the primary cause of the massive post–World War II reduction in deep poverty, especially in Asia.

Socialism focuses on distribution while democratic capitalism focuses on invention and growth. And it is undeniable that the bulk of economic innovation in the past two centuries – from fossil fuel to renewables, and advances in electronics, household appliances, and medical technology – has emerged from societies that practice democratic capitalism, disproportionally America. Moreover, many of those innovations have contributed to human flourishing globally. I will return to some related challenges, but the generally high standard of living that we enjoy can be largely attributed to innovation, so democratic capitalism.

Novak also points out that successful democratic capitalism, generally exercised through corporations, demands teamwork so also mutual trust, compromise, cooperation, and common sense. Corporate communities are where many Americans of diverse backgrounds and beliefs share life together. Middle managers are corporate community builders. It is a not a game for pure individualists.

In sum, Novak’s well-supported argument is essentially pragmatic: “Democratic capitalism looks to the record, rather than to the intentions of rival elites. None have produced an equivalent system of liberties. None have so loosed the bonds of station, rank, peonage, and immobility. None have so raised human expectations. None so value the individual.” Then: “while democratic capitalism is not utopian, its institutions embody a practical wisdom worthy of admiration … democratic capitalism represents a plain sort of wisdom suited to this world.”

Years later, with the world’s one-billion deeply impoverished people in mind, Novak reflected: “Systems that do not move their populations from poverty to decent wealth in less than a generation are flawed and ought to be reformed.” Is there a viable alternative to democratic capitalism? If not, isn’t it the moral choice?

A Few Challenges for Each Perspective

Socialism – that is, shared ownership – arguably leads to more equitable distribution but it does not lead to much innovation and growth; slices are similar but the pie remains the pie. Of known systems, growth in material blessing is best produced by democratic capitalism. At a practical level, how do socialists intend to raise living standards for the billion people who live in abject poverty?

We admire the conviction of Melania and Pinianus, the Roman Christians who gave away all they inherited. But what if, instead of freeing slaves who were re-enslaved and giving cash away, the couple had formed an executive team to manage their assets for the benefit of the entire community? Romans were good at management! What if they had paid former slaves a living wage and built enterprises that challenged the established, exploitative Roman system? They purified themselves and provided short-term relief, but did Melania and Pinianus miss the societal opportunity?

Several authors in Money emphasize that Jesus’ followers in Jerusalem pooled their resources, that it united them and was a vital element of their witness. I don’t doubt it, although it is important to also note that the biblical language reports the practice but does not prescribe it any more than it prescribes that only men with Greek names are to serve under apostles (Acts 6:5). Roughly fifteen years later, believers in Jerusalem were hungry and needed support from other cities (Acts 11:27–30). After another ten to fifteen years, Paul organized famine relief (2 Cor. 8:1–9; Rom. 15:26). Might what began as faithful preparation for Jesus’ return have led to sloth and bailouts – even to Paul’s no-work-no-eat admonition (2 Thess. 3:10). From limited contemporary records we do not know of general famines during the period, so I wonder if famine among Christians was concentrated in Jerusalem, related to poor collective work habits, and was addressed and even subsidized through contributions from other cities. If so, the church at Jerusalem followed a pattern similar to that of almost all utopian communities, failing within a generation or two of a charismatic founder. How will socialists sustain constructive work habits in an entire community?

Money includes two paragraphs from C. S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity in which he wonders about usury. Lewis notes that it was forbidden in Jewish and Christian society through the Middle Ages, also that investment return is quite similar to interest and a basis of modern economies. The modern context is very different, of course, with corporate businesses that span communities, but Lewis was unable to decide whether interest and investment returns are permissible for people of faith. This is a question for all, but especially for democratic capitalists: What was behind the prohibition of usury and how can its objectives be realized today?

Jubilee presents a clearer challenge. It does not seem to have been practiced faithfully, but Moses required the community to reset ownership every fifty years, to give families a fresh start. Democratic capitalists, arguably, approach this objective through a combination of inheritance taxes to reduce the transfer of wealth, and access to education and health care to provide opportunity for new generations. Is this enough? Done well enough? What else might contribute to a regular reset?

We know that wealth can corrupt us. The super-rich purchase private yachts for over $1 billion, city apartments for $100 million, automobiles for $1 million. More ordinary households’ desire for prosperity leads to unhealthy workloads and excessive debt. Friendship is monetized (Clare Coffey, “Selling Friends,” in Money). Personal value and meaning are related to consumption, and we can all cite examples among associates and in popular culture. As Novak emphasized, the three-fold system – economic, political, cultural – cannot thrive “apart from the moral culture that nourishes the virtues on which its existence depends,” rooted in family, churches and neighborhoods. Advocates of democratic capitalism: Is there a moral issue related to excessive consumption and materialism? And if so, how might it be addressed for the good of individuals and communities?

Novak specifically calls out compensation levels at some corporations, often reeking of collusion between governing boards and their consultants, including options that reward holders for stock appreciation unrelated to anything within their control and leading to income levels that bear little relation to contributions. Should more be done to reign in corporate compensation?

Finally, a few public policy thoughts: In Money, Jack Bell (“Saving the Commons”) draws on William Cobbett’s nineteenth-century writing to lament the appropriation of common lands during the British Industrial Revolution. This led, he argues, to diminished care for the land and reduced biodiversity, also to lower productivity and less healthy food. Choices were made by governments, encouraged by wealthy landowners in pursuit of economic development. What other course of action might the government have chosen? In the light of this experience, how should Africans, Asians, and Latin Americans develop their agricultural systems? What care should be taken by corporations as they export Western technology?

In a similar vein, what if a modern virtual ‘“commons” – our personal data, harvested from social media – could not be taken and shared by various tech companies? What if we owned our personal data rather than giving it away in exchange for free apps? We would pay for access but the internet would behave differently. Would we still monetize friendships? How much porn would be consumed if viewers had to provide their names and billing information? Would algorithms feed us only information that stimulates us, with all the related community damage? As with common lands two centuries ago, governments regulate these matters. What choices do we and our governments face today related to social media?

Fitting These Observations Together

Each system upholds different standards and brings very different gifts to our neighbors. Let’s give each its due.

At one level, the systems cannot thrive without one another. The Bruderhof and Capuchins drive automobiles they did not build and employ power sources they did not develop. When ill, they draw upon medical technology they did not invent. Bruderhof Community Playthings are sold to schools and families outside the community. Capuchins, a mendicant order, survive through the generosity of local supporters. Technological and economic advances have been provided by the most productive elements of the economy, largely by corporate owners and workers.

On the other hand, in the face of capitalist excess, Bruderhof and Capuchin friends point in another direction. Their example of community life – sharing everything material, care for one another, modest consumption, all with apparent joy – is respected by the most ardent capitalists. From outside those communities, we may desire homes that sell for millions, then observe the relative simplicity of Capuchin life. We may want the latest automobile model, then read of how the Bruderhof manages a common fleet. We are enticed by advertising, then read Plough’s profound reflections on faith and life. We walk away from those with whom we disagree, then witness the commitment that holds communities together.

You might ask me how to live in community and I might try to answer – but not as an expert and certainly no one will treat me as one. In a similar manner, one might ask a Capuchin friend about economic systems and he might make an attempt – but will not be taken very seriously. We need a humble sense of the gifts we bring (1 Cor. 12).

I first read Novak when I was in business, consulting for multinationals on strategy and organization. What struck me was his claim that the corporation is the vehicle that has, for over two hundred years, been used by God to bless humans materially, that enabling the effectiveness of a corporation is therefore a high calling, a vocation that cooperates with God in the completion of his creation (Gen. 1). I was inspired, and acutely aware of my inadequacy.

Years later, when I moved from corporate to ministry leadership, some who remained in business praised my “move to significance” – an accolade which I firmly rejected, affirming that leadership of a community that blesses neighbors materially cedes nothing to traditional ministry.

Returning to my purpose in writing, to challenge fellow readers of Plough: Affirm corporate life as a calling, and inform it with the insights and values that the Bruderhof have developed in community. The systems complement one another. Join me in hoping that both thrive, in the fullest sense, to further Jesus’ redemptive project by enabling all to flourish.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Francis Koppschall

To follow up on my earlier comment, I would think it clear that supporting Democratic Capitalism is serving mammon. As far as I am aware neither Michael Novak nor Larry Smith argue otherwise. To do so would be an absurdity. It follows then, that what they are arguing is that we can somehow serve both God and mammon. According to the simple, unambiguous words of Jesus that is impossible (Matt 6:24, Luke 16:13). Indeed, any attempt to argue that Jesus didn’t say that, didn’t mean that, was not correct on that point, or that these words are not, or no longer, valid, ends up despising God to whom those words belong (John 14:24), so proving the statement by contradiction. The only logical conclusion that can be reached is that what Novak and Larry Smith are arguing is a moral and religious case that, however “good” it may appear, is not the way of Jesus. It is not, unfortunately, serving God. Eberhard Arnold hit the mark when he described “The Religion of Mammon”. Isn’t it remarkable that the “god” against whom Jesus warned us two thousand years ago is still thriving and still gaining the backing of philosophers and theologians, who are apparently completely unaware of what they are doing? Democratic Capitalism may be “observed” to be good, but that is deceptive: our observation is necessarily limited and we cannot see what its future effects may be. If we are to follow God, if we are to remain the Church, we must accept Jesus’s words as they stand. So, to answer the question what “the Bible prescribes for the entire church”, surely in the light of Jesus’s teaching it is to ask ourselves the question “How can we live a life that does not serve mammon”. That question remains regardless of whether we join a group sharing their property in common. Our calling is to His Kingdom, not the necessarily flawed economic and political kingdoms of this world (Matt 6:33).

Jim Deacove

This article misses the point that the use of money (Capitalism/Communism) whether dollars, euros, kopeks, etc is still the use of money and the analysis of why in an industrialized, over productive society the use of money as the means to distribute goods and services will eventually succumb to its inherent weaknesses. We keep thinking inside the box because we are ingenious at finding more ideas in the box and don’t seem able to think outside the box. I recommend studying the work of Technocracy, Inc. While not a perfect Social Design, the basic flaw of the use of money, no matter how creative, is laid bare and some outside the box thinking explained in breathtaking detail. Yes, it appears that the Money System will always find some way to survive. Recall the Depression Years, when FDR had the chance to implement Technocracy’s Social Design, but instead bowed to the wealthy power brokers. And what creative life raft saved the Money System? The birth of Credit, my friends. Thanks, Jim Deacove

Matthew Pound

Thank you for another thoughtful article on a complicated subject. Reading some of the comments, and thinking through some of my own struggles with these questions, it seems helpful to point out that what we are often upset about is that human beings do not behave as we think they ought to. Therefore, human systems also do not behave the way we think they ought to. One thing that often gets lost in debates about capitalism (an economic system) and socialism (a political system) is that we are not generally arguing about what is desirable, but what is possible, given human nature. Socialism is not an economic system---it does not produce income, create capital, or jobs. It is a political system for how those things ought to be distributed and regulated. Capitalism is an economic system because it does produce those things. What neither system can do, though we may desire it, is produce equally good outcomes for everyone. Free market capitalism is sometimes referred to as a miracle, because no one fully understands or can control how it all works. When we are frustrated with some of its results, it is tempting to assume there is some dark, malevolent force secretly controlling these things. Undoubtedly, there are powerful groups who can and do manipulate it for their own ends. But that is simply human nature, in groups among markets, as among individuals. Socialism, in every historical example has not only had the same inequalities, corruption, and manipulation, but often far worse. I too am frustrated by parts of democratic capitalism and want to work to find ways to improve and better it as a system to better serve all people, especially those at the bottom. However, much anger towards capitalism seems to be based on the fact that it is not perfect, not that it doesn’t work. The reason it is imperfect is precisely because it is a human system, full of imperfect human people. No political or economic system can change human nature, it must work with it. That is why outcomes are far more important than intentions. We are often unaware of a lot of historical and economic examples of when other ideas have been tried and the results they produced. Some fascinating facts: Nothing has done more to lift more people out of poverty around the world than free markets. It perhaps doesn’t feel noble or loving, and maybe it isn’t. But the fact remains, if our concern is primarily for the wellbeing and improvement of the quality of life for the poor, encouraging free markets and democratic capitalism is hands down, the best way to change their poverty into prosperity. In China alone, almost 1 billion people have escaped severe poverty due to freer markets in the last 50 years. We must judge by good effects, not good intentions. In America in particular, the poverty rate among households with at least one full time worker is about 3%. That is astonishing and a big part of the reason why so many people from other nations are still desperate to come to America (from parts of Europe and Latin America). Consider also that the people who live in poverty in the US typically only stay there 3 years or less. In other words, people are generally able to escape poverty within 3 years in the US. The percentage of people living in poverty stays roughly the same because of new people immigrating to the country. And even those people generally move up and out of poverty in 3 years or less. We should be angry about injustice and human suffering. But let us be wise in our anger. When our car has a minor issue, we don’t total the car and curse it for ruining transportation. When a medical procedure saves our life, we don’t complain about a minor side effect. When an economic system lifts billions of people out of poverty, and improves their standard of living, we can and should continue to study and try to improve it, but let us also be grateful and humble to respect what it has done, even if it still leaves work to be done. We must remember too, that chosen collectivism is an entirely different thing from enforced collectivism. A group of like-minded people willingly choosing to renounce private property and hold their goods in common for the good of all is a noble, admirable enterprise. To give a few individuals power to compel others through force, and violence to do something they do not want to do, even in the name of the common good, is evil and wrong. In summary, I appreciate this article’s efforts to balance the positive elements of different points of view for the general welfare. Having lived and worked with very poor communities in Asia for the last 10 years, I feel tremendous gratitude to have been born in a democratic, capitalist country like America. Let us work together to make it better, but let us also humbly strive to understand the ideas and processes which has already made it great and unique in the world.

Larry R.

First off, I appreciate Mr. Smith's tone. Not trying to "create enemies" like so many of us are doing today. I'll try to keep that tone here. So many things here to address, I think a whole series could come out of questions stemming from Mr. Smith's response. Though I must admit, I have not read all the article's he's referring to. But here's a few points that need to be fleshed out by the Church: 1) "Capitalism lifts people out of poverty." Not really. It is highly dependent on poverty for our cheap "material goods." Just think sweat shops, etc. 2) There's an echoing of what I call "intentional limited accounting" going on in the Milton Friedman flavor of "capitalism is great, because look at the real consequences: everybody has more things!" kinda argument. While I certainly agree that we have lots of "materials" that are bought and sold, I cannot agree that this is the equivalent to "progress." Lots of us are extremely unhealthy physically, and mentally, and spiritually precisely because of our economic situation. That is to say, having lots of materials is very different from having a village to share life with. 3) Related to #2, We need to be more specific about what we're talking about when we use the word "capitalism." Way too many things are thrown in that category. I'll give you two examples and you can imagine up all kinds of examples that fall in the middle somewhere. The first example comes out of a conversation I've had with someone at the Seminary I work with -- they called Joel Salatin a "capitalist, and with a nasty tone. I responded, "Well, yeah, if you mean 'capitalist' in the healthiest sense of the word." So, the first example of capitalism is a small farm that enhances the life of their land and sells a great product. That's, to me, a great version of capitalism. The second example: someone 'designs' a sweet beverage and sells it to whomever would be interested. They make tons of money, and let's even say they pay their workers well. But they mine their water from some poor village in a far away country that doesn't regulate foreign businesses taking resources, and the consumers are all unhealthier because of this product. Now, the question that no-one asks: Is this person a "productive member of society?" I think you can answer that question. Both of these examples are thrown under the same term as capitalism, yet are very different from one another. Mr. Smith subtly equates them when he points out the fact that the Bruderhof communities sell toys, which I think is an all too common mistake, because we aren't specific enough with our language. 4) "Acts didn't prescribe sharing resources." Well, Jesus basically did. "Refuse nothing of anyone who asks of you." Etc, etc. Too many examples to count. When someone makes an inherently "Christian" argument, but never cites Jesus, watch out. They could be arguing for something else entirely. They may even be very explicit about what they're arguing for in their title! 5) Our comforts, our privilege and entitlements, all come at ecological and often hidden societal costs. We must remember Amartya Sen, the Nobel prize winning economist who showed a strong correlation between income and carbon footprint -- that is, the more comfortable we are monetarily, the more resources we are (most likely) using. The honest word for this is, again, entitlement. We feel entitled to the vast amounts of God's resources we burn through (which God makes to fall on all God's people evenly; which is to say humans are the only ones to take them from these people and to give them to the few). I hear young students all the time talk about privilege in such a way that simkply compares americans to americans. But in the world's perpective, all americans are super privileged and use up lots more than our share of the earth's resources. (These same students critique 'capitalism' ad nauseum then turn around and support it with all their dollars, which I see as a failure of our education system just as much as their own moving their 'academic brain' into practice.) Anyhow, lots more can be said, and hopefully some of this was covered in the "Money" issue Mr. Smith cites. But these are some points that I saw missing from the discussion. Again, I'm thankful for his tone in not 'demonizing.' One book I would add to people's radar is Graeber and Wengrow's "The Dawn of Everything." While I don't think these guys understand much about Christianity, the book points to the historical record on where we get our ideas on freedom from (certain parts of the American indigenous people) and asks a big question, after showing the vast array of lifestyles people all over the world have lived: "How is it that we've gotten stuck in imagining up, and then living into, different societal structures?"

Francis Koppschall

As an accountant of many years, I read this essay with interest. You appear to argue that Christians should support Democratic Capitalism. Because Christians serve God, for your argument to succeed you need to persuade us either: 1) that supporting Democratic Capitalism – a system whose driving force is the pursuit of money – is not “serving mammon”, or 2) that serving both God and mammon is, in fact, possible. Which is it?

Linda wilson

G. K. Chesterton disliked Capitalism because it exploited people and Communism (which some have taken to include Socialism, but I am not sure he would agree) because it oppresses people. In Canada and many other western democracies there is a system that merges Capitalism and Socialism, with each keeping the other in check. It is certainly not perfect, but then, neither is American Capitalism. In the end both systems come down to wealth and how it is managed. If I understand Adam Smith, who many believe began the Capitalist enterprise, he believed that Capitalism (though I believe he had a different name for it) would enrich everyone. But that has not happened. I think many Capitalists need to be reminded of James 5:1 - 6 “ 1Come now, you who are rich, weep and wail over the misery to come upon you. 2Your riches have rotted and moths have eaten your clothes. 3Your gold and silver are corroded. Their corrosion will testify against you and consume your flesh like fire. You have hoarded treasure in the last days. 4Look, the wages you withheld from the workmen who mowed your fields are crying out against you. The cries of the harvesters have reached the ears of the Lord of Hosts. 5You have lived on earth in luxury and self-indulgence. You have fattened your hearts in the day of slaughter. 6You have condemned and murdered the righteous, who did not resist you.” I think we have to be careful. I told my pastor once that I am a Humanist, and he said that is no way to be because Humanism replaces the creator with the creature. He said he was a Capitalist. I said that replaces the creator with the creation of the creature. Of course, neither is entirely correct, for both of us are Christians first and my Humanism and his Capitalism are both placed within the constraints of Scripture that overrides anything else we may believe. I think anyone who works 40 hours a week should earn a living wage, they are not lazy, and I think James would agree with me. I also think much of our innovation is the result of a Liberal Arts education that trains the imagination as it trains the intellect. Though the imagination is incentivized by “capital.” Cordially, J. D. Wilson, Jr.

Michael Nacrelli

Question(s) for Marianne: What percentage of US wealth is held by Asian Americans, and how does this compare to their percentage of the population? As for Latin America, I don't think racism is the main problem, as racial lines are often very blurred there. Rather, it seems the bigger issue is the lack of real democracy, transparency, and rule of law. Entrenched oligarchy, corruption, cronyism, nepotism, and violent suppression of unions and advocates of social/political/economic reform have long plagued the region. Of course, US meddling has generally exacerbated these problems. "Democratic" capitalism is a misnomer for most Latin American economies.

Larry Smith

Author’s Response: Marianne Fisher makes two primary points each of which, ironically, supports my thesis and therefore Novak’s. First, that Latin America was and is more dominated by colonial racism than what became the USA and Canada demonstrates that democratic capitalism, including “a polity that respects life and liberty and is enabled by cultural institutions that hold to ideals of liberty and justice” (as in my article) is essential to growing prosperity. Ditto for the less dramatic but still important lack of egalitarianism in the USA. To her point, Americans could be collectively more prosperous if our system embraced more of us. Second, she advocates and romanticizes the mix of citizen security and capitalism that characterizes the social democratic system typical in Europe (a system which I experience as a resident of Italy). Europe strikes a different balance than America, but it is well within the bounds of Novak’s democratic capitalism — and it is important to acknowledge that American economic growth has outperformed Europe’s for decades and attracted many more European immigrants than the number of Americans that moved to Europe. Ms. Fisher’s other points are more rant than reasoned. Her concern about racism and its ongoing effects in America and Latin America is heart-felt, I am sure, and reflection on how that might be rectified or at least addressed through the economic system is worthwhile. It does not follow, however, that community ownership will address the sin of racism any more effectively than private ownership. And her concern for political dark money — sourced from a wide range of donors, not limited to those nefarious corporations — deserves careful reflection on the value of transparency and the rights of donors, but it does not relate to Novak.

Michael Nacrelli

@Marianne I think the economies of Canada and Western Europe are better described as welfare capitalism rather than socialism. The basic economic engine is still (mostly) private enterprise, but with heavy government regulation, taxation, etc.

Marianne Fisher

I too have read Michael Novak's "The Spirit of Democratic Capitalism", and what I have always found most interesting is that he compared Northern with Latin America. That was a cheap shot on Novak's part, because Latin America, while advantaged with various resources, was disadvantaged with European domination, i.e., imperialism, based on racism. To this day the social and economic structure in much of Latin America is based on a racial hierarchy, with the darkest (former slaves) are at the bottom, followed by Native Americans (Maya / Aztec / etc.), followed by mestizos (mixed) with the most white at the top. And we have a similar situation in America, where white households, generally, have 10 times the wealth of black households. And Native American households have about 8 cents of wealth for every dollar of wealth that white, non-Hispanic households have. Democratic capitalism is great for those who are not facing the racial inequities which are still baked into the American system. It's also important to remember that Democratic Capitalism in America has been based, since Reagan, on a free market economy that has become increasingly dominated by corporations, whose dark money contributions to politicians give them the right to make the laws and regulations for themselves. To quote the Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance: "Corporations today operate according to a model of corporate governance known as “shareholder primacy.” This theory claims that the purpose of a corporation is to generate returns for shareholders, and that decision-making should be focused on a singular goal: maximizing shareholder value. This single-minded focus—which often comes at the expense of investments in workers, innovation, and long-term growth—has contributed to today’s high-profit, low wage economy... With corporate rights should come societal responsibilities, but the rules of corporate America today do not guarantee that firms advance the public interest." Meanwhile, to look at Canada and much of Europe, the Social Democratic system seems to be providing far more equity, social systems, and social justice than the American system. In America the primary cause of bankruptcy is medical debt because there is no universal health care - instead what everyone calls "the health care debate" is actually about keeping private health insurance industries running. In Social Democratic systems there is universal health care, universal free education (generally through college), paid family leave, and other benefits that enable people to get jobs, work, and not be afraid of losing the job or their savings because of medical or student debt, or taking time off for the birth of a child. Novak's book is both naive about real world economics even for his time and seriously outdated. It is a polemic, not a serious study of either economics or history. There is nothing "moral" about the "democratic capitalism" that we currently have, which is neither democratic nor free market capitalism, dominated as it is by monopolies, dark money, and (to be brutally honest) a political system and a SCOTUS that defends the rights of corporations over the rights of the individuals working for them.