Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Serving Kings

-

Up Hill

-

City of Bones, City of Graces

-

Small Acts of Grace

-

In the Valley of Lemons

-

City of Clubs

-

Save Your Sympathy

-

From “In the Holy Nativity of Our Lord”

-

Digging Deeper: Issue 23

-

Beneath the Tree of Life

-

Sidewalk Ballet

-

The Eternal People

-

Robert Hayden’s “Those Winter Sundays”

-

The Pilgrim City

-

Not Just Personal

-

Editors’ Picks Issue 23

-

Madeleine Delbrêl

-

Covering the Cover: In Search of a City

-

Urban Series (Neighborhood)

-

In Search of a City

-

Readers Respond: Issue 23

-

Family and Friends: Issue 23

-

One Inch off the Ground

This article was originally published on December 2, 2019.

When I was a child in Northern Ireland, the awareness of violence suffused our daily lives. The year 1981 began in bloodshed: A Catholic Republican Socialist, Bernadette McAliskey, and her husband were attacked in their home by loyalist gunmen. An elderly Protestant Unionist, Sir Norman Stronge, and his only son were shot dead in retaliation by an Irish Republican Army (IRA) gang who then burned their house to the ground.

Spring brought the onset of the hunger strikes, which were to radicalize nationalist Ireland. A number of IRA prisoners vowed to starve themselves to death unless the British government agreed to their demands for political status in jail. The first man to go on hunger strike was Bobby Sands. A month into his fast, he was elected to parliament as a member of the Sinn Féin party. The following month, he became the first of ten hunger strikers to die that year. In Belfast, the news was accompanied by riots.

Republican mural of Bobby Sands, IRA prisoner and hunger striker, on the Falls Road, West Belfast.

Photographs courtesy of the author

I was in my final year of primary school in South Belfast. Most of the children at my school were Protestant. I don’t recall much talk about politics there, but in this instance the wider anxiety seeped into our conversation. One worried boy said that for the next few months it would surely be safer not to go into the center of town. He had probably heard this from his parents, mindful of recent IRA firebomb attacks on shops. But I remember thinking that it didn’t make sense. How on earth could you not go into town? My family lived outside Belfast, but my father worked in the city center, and he drove us children across town to school.

At the same time, over in West Belfast, a seven-year-old Catholic boy named James Moyna was being drawn into the riots, excited as well as frightened. One day when the police fired plastic bullets to disperse the crowd, he jumped to avoid one skittering toward him, and it hit an elderly lady on the ankle. He felt guilty that it hadn’t hit him.

Everyone in Northern Ireland at that time carried personalized maps in their heads – of where it might be safe for them to go, or where they were most likely to come under threat. The young Moyna, for example, would never stray into the nearby Protestant heartland of the Shankill Road. For him, Protestants were represented by the divisive figure of the Reverend Ian Paisley, ranting against Catholicism on the television.

But these territorial maps, even when carefully observed, didn’t always keep people safe. Belfast had a way of unleashing random shocks upon its citizens. People might find themselves unwittingly standing too close to a car bomb meant for the security forces, or in a bus station or pub at exactly the wrong time.

And then there was the deepest instinct of paramilitarism, to plant an unease so profound that even the safe places were no longer safe, psychologically or otherwise. The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) murdered civilians in drive-by shootings in Catholic streets and homes; in the early 1970s, Moyna’s mother and grandmother had been “burned out” of their house three times. The IRA often performed its targeted assassinations by simply ringing a doorbell and shooting the householder. Cars zipped around the city, delivering death. “We know where you live” was a dark threat that echoed through the conflict. It meant that the map of danger included home.

In that summer of 1981, however, something happened to redraw James Moyna’s map. He was selected by the Euro-Children charity to spend the summer with a German family. Father Robert Matthieu, a Belgian priest, designed the program to give disadvantaged Belfast schoolchildren – mainly from Catholic backgrounds – a break from the Troubles.

James Moyna

Photograph by Justin Kernoghan

The lively Moyna was suddenly placed in a very different environment from his crowded, terraced family home. He found himself staying with the Heinz family: Heino and Gabi and their two young sons, who were close to him in age.

It was disorienting, Moyna recalls: “There was no police, no army on the street. The family was wealthy and living in all that space, with lots of bathrooms. Back home we paid the neighbors to use their bath because we didn’t have one yet.” There were plays and tennis and horseback riding. There was a language barrier – “they immediately set about teaching me German” – and a different worldview.

Along with his suitcase, one of the things that Moyna brought with him to Germany was a hearty dislike of Protestants. Gabi Heinz explained to him that Protestants didn’t have to be bad people. In her eagerness to convince him, she mentioned a number of friendly Protestant neighbors who had come to visit him and whose children he had often played with. Moyna listened very attentively to the names. The next day, he pitched a stone through the window of every family she had mentioned.

But in time, with patience and generosity, Moyna’s hosts opened his own window on a wider, suddenly vivid world. Away from home, he began to appreciate what the Belfast-born poet Louis MacNeice meant when he wrote that the “world is crazier and more of it than we think / incorrigibly plural.” Moyna returned summer after summer, even accompanying the Heinz family on trips to other parts of Europe. “The lens through which I saw life was changed.”

Back home in Belfast, there was still some cause for wariness. He remembers one Good Friday in particular: “I said to my mother, ‘What’s for tea?’ And she said ‘brown fish.’ And I hated brown fish, so I went out and I joined a cross-community peace walk from Clonard Monastery.” Along the way, the peace walkers ran into a notorious loyalist firebrand named George Seawright, “yelling at the top of his voice, ‘You got into the Shankill, but you’ll not get out!’” Seawright would later be shot dead on the Shankill by republican paramilitaries, in 1987. But on that day his words struck fear into the eleven-year-old Moyna: “I ran back home. I was never as grateful to eat brown fish in my life.”

At the same time, however, other factors were changing Moyna’s sense of Belfast’s geography. In his first year at his Christian Brothers’ secondary school, he was given the chance to take up the flute. “I had already been playing Irish traditional music on the tin whistle. I brought [the flute] home, and I assembled it and could actually play it.”

He pitched a stone through the window of every family she had mentioned.

His flute teacher, Miss Bolger, was a Protestant and a member of the renowned 39th Old Boys Flute Band, which had produced the world-famous flutist James Galway, who occasionally dropped back in for rehearsals. Noting Moyna’s ability, Bolger invited him to come along to band rehearsals, and twice a week he traveled to the Protestant Donegall Pass for flute practice. Moyna went on to join the City of Belfast Youth Orchestra, and Clonard Monastery made a room available where he and his Protestant friends from the orchestra could play music undisturbed. Music was a different conversation, one with the power to blur the city’s dividing lines.

Today, moyna is forty-five, and a teacher at St. Bernard’s Primary School in East Belfast, where he leads the “shared education project” in conjunction with two other local primary schools, Cregagh and Lisnasharragh. The pupils of St. Bernard’s are predominantly Catholic, and those of the other two schools are mainly Protestant.

For a set number of days per term, the classes from P4 up to P7 – with children aged roughly from seven to eleven – are mingled. The special topic that the schools have agreed on for these lessons is information and communications technology, which can involve everything from coding and constructing a drone to script-writing and digitally animating a play.

In each classroom, there is a mix of red and blue sweaters; small heads are bent studiously over iPads as the children work on graphic design images of Northern Irish landmarks such as the hexagonal rocks of the Giant’s Causeway and Samson and Goliath, the massive yellow gantry cranes of Harland and Wolff shipyard that loom over the complicated city.

There are currently sixty thousand young people involved in shared education in six hundred schools across Northern Ireland. Because this mingling of Catholic and Protestant children is primarily based on shared lessons and activities, it lacks the clunky self-consciousness of some “integrated” initiatives of the past.

Paul Smyth, a youth worker since the early 1980s, remembers numerous projects that ranged from “woeful” to “really quite good.” In his early work with the Peace People, they would take cross-community groups to Norway and have “some really meaningful conversations.” But he also recalls a friend’s Catholic daughters being flummoxed by a bizarre day in which Protestant pupils were ushered into their school hall and seated on the opposite side from the Catholic pupils, after which there was Irish dancing on stage and someone read a poem. The two groups never actually mixed.

He laughs as he recalls a recent episode of the hit television comedy Derry Girls, set in Northern Ireland in the mid-1990s, which satirized an old-style exercise in reconciliation. In the show, a matinee-idol young priest attempts to lead the Catholic convent school girls and some visiting Protestant boys in a rather contrived discussion of their similarities during a residential weekend. But the teenagers – clad in “friends across the barricades” T-shirts – can only manage to come up with differences, and before long the blackboard is crammed with their examples: “Catholics really buzz off statues.” “Protestants hate ABBA.” “Catholic gravy is all Bisto.” “Protestants love soup.”

Only 7 percent of Northern Ireland pupils go to schools that are officially integrated.

The episode was a great hit in Northern Ireland and beyond. The Irish writer Marian Keyes jokily professed herself outraged at “the slur on Catholic gravy.” Protestant ABBA fans made humorous protests, including that of a flute band from Banbridge, which put out a Facebook statement publicly naming two of its band members as “fans of the Swedish singing sensations.” The show’s writer, Lisa McGee, who is from a Derry Catholic background, made it clear that the ABBA suggestion was not her personal view but that of a character, the reliably dippy Orla McCool.

It was a reminder that – when circumstances allow – the “two communities” do have one definite thing in common: they like a laugh. There is a particular, familiar texture to conversation in Belfast, a quickness to the banter, that is one of the things I miss when I’m away.

When the protestant children visit St. Bernard’s, they walk past a large picture of Pope Francis just inside the front doorway. If it ever did strike them as unusual, it doesn’t seem to now. I ask if they found the school different at all when they first arrived and one girl says, “I kept getting lost!”

Religion is not uppermost in the minds of these children. They nod when Moyna asks them if they know that their schools are mainly divided between Catholic and Protestant, as are the majority of schools in Northern Ireland. It’s the legacy of a system whereby the Catholic Church runs its own, state-funded “maintained” schools, with separate teacher training. Alongside them run the “controlled” state-funded schools, which are open to pupils of all faiths and none, and in practice are two-thirds Protestant. While there is often more mixing at the secondary-school level, only 7 percent of Northern Ireland pupils go to schools that are officially integrated.

James Moyna teaching a “shared education” class mingling Catholic and Protestant children from three local primary schools.

Paul Close, the project coordinator for shared education, says that it isn’t only about bringing together children of different backgrounds, but also teachers. Close himself had little contact with Protestants his own age until he attended a university in London and “ended up living with two lads from Larne. We discussed many times that we would probably never have met” in the home country they all share.

If an active effort had not been made to bring these children together, their early lives might never have converged either. As well as being mainly educated in separate primary schools, these children have a tendency to stick closely to the streets immediately near school and home, and Protestant and Catholic areas are marked out by commonly understood boundaries.

Moyna says of the St. Bernard’s children, “Our children never walked up the Cregagh Road. And the Cregagh children wouldn’t have known where St. Bernard’s was, because that’s not somewhere they would play or explore.”

“Would you now say hello if you saw each other outside school?” Moyna asks his class.

“Yes,” they all agree.

One boy from Cregagh tells me, “I play football with boys from Lisnasharragh” – the other Protestant primary. But then he adds, “I have lots of Catholic friends.”

David Heggarty, the headmaster of Cregagh, is himself a former pupil. He did not meet Catholics his own age until he was a teenager, when the Royal Ulster Constabulary organized a cross-community hill walk. He and Philip Monks, the Lisnasharragh headmaster, both like how the program shares teaching skills and resources across the three schools. Parents look favorably on it, too. Research indicates a positive “attitudinal shift” in youth who have been involved.

“We’re neighbors,” Heggarty says. “There’s a hope that the children will bump into each other at the GP’s [doctor’s office] or the leisure center and say hello. The little friendships that have sparked up have a real bit of depth to them.”

Heggarty also notes that the Protestant Cregagh neighborhood has lately become home to a number of Catholic immigrants from Eastern Europe. In modern Belfast, immigration – predominantly Polish – is now gently complicating the historic Catholic-Protestant, Irish-British religious and cultural divides.

An Ulster Volunteer Force loyalist paramilitary mural on the Newtownards Road, East Belfast

I had a map, too. I was born in Belfast, but when I was six years old my family moved out to a leafy suburb. We had a detached house with a large garden, and the streets around it were calm. I was lucky to live there.

Still, there was unease. My father was a barrister who, in the early 1980s, also entered Unionist politics. The IRA had a very broad range of “legitimate targets,” the phrase which it regularly used to describe anyone it felt positive about killing. That category included Unionist politicians, one of whom, a young law lecturer named Edgar Graham, was shot dead in Queen’s University, opposite my school.

I began to take mental note of the statements offered to justify killing. The loyalist paramilitaries were more overtly sectarian, making it clear that, while they would rather kill Irish republicans, any Catholic was a potential target. They argued that striking random horror into the wider Catholic community would result in nationalist pressure on the IRA to cease its campaign. The theory was as strategically wrong as it was morally appalling.

The IRA and the Irish National Liberation Army preferred to argue that their killing was political rather than sectarian, but in reality “political” seemed to mean that they could kill whomever they wanted. And numerous IRA atrocities were explicitly sectarian – among them the 1976 Kingsmill massacre, in which gunmen ordered eleven Protestant workmen out of their minibus and shot them, and the 1993 Shankill Road bomb, which killed Protestants queuing to buy fish. Down near the Irish border, there was a long and relentless IRA campaign to eliminate Protestants from border farms and villages and drive families further back into nearby towns.

Both republican and loyalist paramilitaries called themselves “defenders” of their communities. To have any credibility as a “defender,” one needs an “attacker.” In a curious way, each group relied on the other in order to survive.

I began to take mental note of the statements offered to justify killing.

My map did not contain suspicion of Catholics in general: we had Catholic relatives and friends. But it did include a deep apprehension of Irish republicans – not because they wanted a united Ireland, but because they supported killing those who thought differently. Republican strongholds in Belfast, such as the Falls Road, felt fenced-off accordingly.

It wasn’t that I didn’t think there were good people there, who were opposed to sectarian violence. It was just that if you happened to encounter someone who was for violence, and to whom your specific background might turn out to be of interest, there generally wasn’t much the nonviolent people could do about it.

When the ceasefires were declared, I was in my early twenties and living in London, working as a newspaper reporter. From 1995 onward, I was frequently sent back to Belfast to cover events.

Times had changed. I went to the Falls Road for the first time. I covered the first-ever Sinn Féin rally to take place in Belfast’s Ulster Hall – a symbolic event at a site where Unionists had famously rallied in opposition to Home Rule.

Gerry Kelly, an IRA bomber and hunger striker turned Sinn Féin politician, swept in to wild applause. There was a striking display of Irish dancing from a troupe of young girls, applauded by party leaders Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness with avuncular approval from the stage. I could sense the communal excitement, the heavy tug of belonging. The excitement, however, did not include me. Although I was with other reporters, I felt on edge. I did not put money in the collection box that was emphatically passed around. I hoped that no one would notice.

Reporters from other places were free to look upon the Northern Ireland story as the fascinating, if depressing, jostling of two political tribes. But those from Northern Ireland carried our personal history with us on assignments. The Guardian reporter Henry McDonald, a Catholic from Belfast, had as a child narrowly survived a UVF bomb planted just outside his home. McDonald recently described how he traveled “gripped by fear” to interview the UVF leadership in 1993, one of the edgiest years. As a nervy icebreaker, he told them the story of the bomb, and one replied with a snigger, “Sorry, son. It was nothing personal.”

Yet the suffering that such groups caused could not have been more personal. Each new attack left its legacy of pain and rage.

On good friday, 1998, the Belfast Agreement brought an official end to the Troubles. Many hoped that with the ceasefires, the divisions between people would naturally start to heal. The international media moved on. And yet, twenty-one years later, the healing in Northern Ireland does not seem to have taken place.

At one level, Belfast has been transformed. The city center is crammed with new boutiques and coffee shops. The Cathedral Quarter is packed with restaurants and strung with fairy lights, and the sleek Europa hotel is no longer the most-bombed hotel in Europe.

Wire cages still shield the houses from potential attack.

But politics remains split along sectarian lines, even more so than during the worst of the violence. The center ground has disintegrated, with power concentrated in the parties that were formerly at the extremes. Voters fear shifting position in general elections, in case their community is flattened by the other side. The delicately negotiated Stormont government collapsed in January 2017, and has not sat since.

While Stormont has been empty, the streets have been busy. The paramilitaries, including “dissident” republicans such as the New IRA and the loyalist UVF and UDA, have consolidated control in their areas. They are active in criminality and drug-dealing as well as influential in politics. Both sides have been publicly flexing their muscles with veiled or open threats of violence in negotiations over aspects of Brexit. There is a very low conviction rate for the perpetrators of regular paramilitary shootings and beatings within communities – witnesses are, understandably, reluctant to give evidence.

Against the hope that a younger generation would move decisively away from the cruelty of the past, a minority choose to celebrate it. For some who don’t fully remember the reality, it has already become “radical chic.” Nostalgic visions of the conflict, fed by unrepentant paramilitary commemorations, help create new victims: when the stellar young journalist Lyra McKee was killed by a New IRA bullet at a riot in Derry last April, it felt as if the worst of the old Northern Ireland had reared up to destroy the best of the new – and yet most of the rioters were younger than McKee.

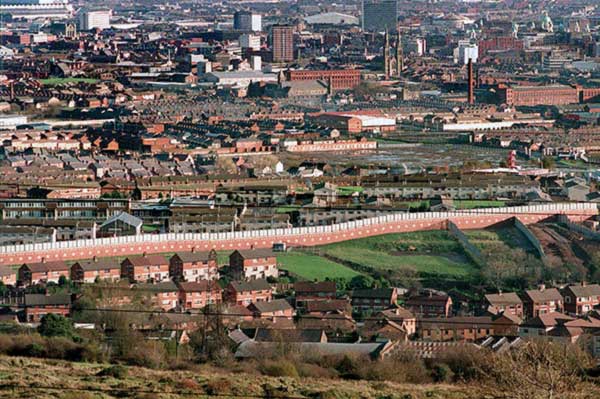

In West and North Belfast, territories are heavily demarcated by the “peace walls.” Since 1998, such gates, fences, and barriers have proliferated. There are now ninety-seven such mini-partitions in Belfast alone, “protecting” small communities from one another. At night, certain gates that are open during the day are locked up, as the city seals tight its little cantons.

An aerial view of one of the “peace walls” separating Protestant and Catholic communities in Belfast. Many of the barriers are opened to allow some access during the day and locked at night.

Back in Belfast, I take an informal drive with James Moyna around the peace walls. Along the way, we take in the Shankill and the Falls. Near where Moyna grew up, wire cages still shield the houses from potential attack.

The “Troubles Tour” has become a thriving local industry, whereby Belfast parades its dysfunction for visiting tourists. The murals are a form of advertising, part of the extended battle over who tells the official story. Republican murals have been gradually altered to phase out blatantly violent representations, and instead depict the IRA campaign as a natural bedfellow to selected international struggles such as those in Palestine, Cuba, Catalonia, and anti-apartheid South Africa. The loyalist walls, however, often favor brutal depictions of balaclava-clad gunmen, although there are also historical and cultural murals and a montage of the Queen.

Every year, Belfast loyalists build huge, teetering bonfires to set alight on the eve of their July 12th commemorations of the 1690 victory of the Protestant King William of Orange’s forces over those of the Catholic King James II. Since 1998, these constructions have grown steadily bigger. Each one is intricately pieced together to a great height, displaying melancholy remnants of the engineering talent that the builders’ forefathers once put to use in Belfast shipyards. Yet these edifices don’t sail forth to the rest of the world. Adorned with effigies of loyalism’s opponents, they burn down to ash.

Belfast itself doesn’t burn, but it smolders.

There is another story in Northern Ireland, too often untold. It is lived by all the people who persistently tried – and still do try – to write a better map.

One of the most heartbreaking incidents of the Troubles happened in 1998, when the Loyalist Volunteer Force, a splinter group not on ceasefire, shot dead two men in the Armagh village of Poyntzpass. The pair were drinking together in the Railway Bar, and their sectarian killers assumed that both were Catholic. But Philip Allen was Protestant. His Catholic friend Damien Trainor was going to be best man at his wedding.

Friendship meant a different, stronger kind of giving.

The horror of the killings went around the world. But perhaps we should think longer on their deep friendship, and so many other friendships that quietly defied the oppressive logic of the Troubles. The language of the conflict centered on taking: paramilitaries took up arms, took control of areas, and then took lives. To their members, giving meant giving way and giving up.

Yet friendship meant a different, stronger kind of giving. Friendship altered Moyna’s vision from that of a child who hated Protestants – and steered him away from the dangerous path down which such feelings might have led him in Troubles-era Belfast. He thinks often, he says, of the various adults who offered him chances without expecting any guarantees of reward – the Heinz family, who welcomed in a strange child from a beleaguered city, and the local teachers and musicians of both backgrounds who encouraged his musical talent and provided a context for it to mature.

“These people were my guardian angels,” says Moyna. “People who gave.”

Sign up for the Plough Weekly email

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.