Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Womb to Tomb

-

Insights on the Gospel of Life

-

A World Where Abortion Is Unthinkable

-

Gardening with Guns

-

A Good Death

-

Behold the Glory of Pigs

-

Polyface Logic

-

Nature Is Sacred Stuff

-

Editors’ Picks Issue 10

-

Poem: An Apology for Vivian

-

Stewarding Mercy

-

Learning to Love Goodness

-

Who Invented Thirst and Water?

-

Muhammad Ali

-

Are Humans Sacred?

-

Islands

-

Readers Respond Issue 10

-

Consistent Life Network

-

Death Knell for Just War

-

Remembering Daniel Berrigan

-

My Return to Iraq

-

Pursuing Happiness

-

The Gospel of Life

-

Building the Jesus Movement

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

Was Jesus serious when he said, in Matthew 25, that we’ll find him in places like prison? If he spent his time with the least of his society, discipleship would seem to require the same of us. With that in mind, I visited Riverbend Maximum Security Institution in Nashville, Tennessee, as regularly as possible for four years, building relationships with the men inside while serving as a volunteer chaplain. I sought to see my visits as encounters with the incarnational body and blood of Christ.

As I bore witness to the dehumanizing drama of life behind these retributive walls of exile, I was often left with that timeless question asked from Job to Jesus: “Where are you, God?” And sometimes when we don’t have answers, we just tell stories.

That particular Friday began as my Fridays usually did: quiet morning of conversation with my grandmother over coffee and muffins, silent meditation, and a thirty-minute drive to the prison. My assignment was Unit 4, a maximum-security unit where two of the four pods were designated as “mental health.” This unit was certainly the most violent in the prison, as the stress levels of inmates and staff stayed dangerously high.

Before entering, an officer warned me the pod had “been crazy” all day. Acknowledging his caution, I called into the radio unit, and within seconds, the thick steel door and iron gate opened, granting me access to the pod. I shouted from the entrance that I would be around to each cell. I started with Mr. Freeman, a man I met just a few weeks earlier in the infirmary after he had set fire to the shirt on his back to get attention. Next, I moved to the cell of Mr. Saylor, who within two hours would be rushed to the hospital, close to death.

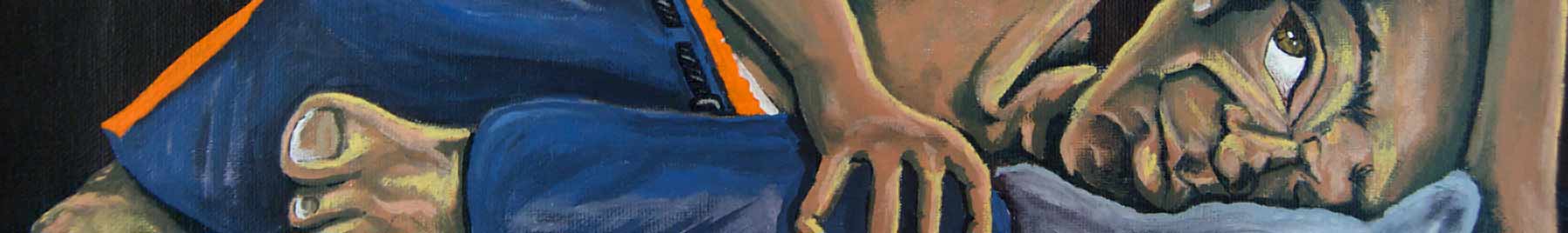

Alan Norberg, Counting Time

“Howdy, Mr. Saylor,” I greeted cordially. Having never met him before, I introduced myself. His clean face looked young, and I guessed we must be very close in age.

“Are you doing OK?” I asked him smiling.

Mr. Saylor tilted his head as he looked at me through the glass. Then his right hand took a small razor and quickly cut his left forearm. Raking his hand through the blood, he then smeared it down his face, over his nose, mouth, and chin. One glob rested above his eye. His whole demeanor suggested he wanted me to be intimidated, impressed, perhaps even to quiver in awe.

“Is there anything I can do for you?” I asked.

“Just get me a straight ticket to the road to hell!” He had a lively country accent, and he swayed back and forth as he spoke. I asked him why he wanted to go to hell. “Everybody wants to go hell! It’ll be fun,” he told me, the fire in his eyes intensifying, “All that buurrrnin!” He then lifted his left arm; it was spotted with burn marks and blood from various razor cuts that day.

“That looks quite painful,” I confessed. When I asked him what was wrong, he shouted at me: “Man, I’m just fuckin’ tired of it! Nobody here cares about me!”

I looked him straight in the eyes, and said as genuinely as I could, “I’m trying to care, Mr. Saylor. That’s why I’m standing here talking to you.”

“Ah, you don’t give a shit about me,” he hollered, turning around laughing. He walked back toward his bed, and I knew he had no reason to believe I cared.

When he returned to the narrow window, I told him I needed to call medical since he was bleeding. I asked an officer to make the call, but the officer asked me to leave the pod. My immediate protests did not sway him. Apologizing to Mr. Saylor, I turned to walk down the stairs, passing three officers on their way up to his cell.

Before I reached the floor, I heard one shout, “He’s squirting! He got an artery!” The corporal shouted through the radio unit, “Get medical in here now!” Then he yelled to me to run find latex gloves in the central staff pod. Searching frantically, I located two pairs and rushed back into the pod and up the stairs. Taking the gloves from me, the corporal instructed me to wait on the lower level. Four officers gathered at his open door, and from where I stood below, I could see it all.

Just as I had walked away from Mr. Saylor’s door, he had sliced clean through an artery in the bend of his left arm. Streaks of blood now covered his whitewashed walls, as if he had squeezed a squirt bottle while turning circles in the room. I saw him sitting calmly on his bed at the back of the cell, a laser quivering on his chest from the Taser one CO (correctional officer) pointed at him. A large gash stretched across his arm, blood streaming down his forearm, onto his pants. His face, shirt, and bed were red with blood, and he just sat there, still, smiling at the prison staff in his doorway. The COs handcuffed him so he couldn’t cut anymore, and the medical team wrapped a bandage around the severed artery. But by that time, he had already lost so much blood that he soon collapsed, unconscious.

Four COs carried him down the stairs, his arms and legs stretched out and his head hanging back over their shoulders. I stood there, perhaps in shock, unaware of any conscious thoughts. Suddenly, I regained a sense of awareness as I heard another man calling for me. Hustling up the stairs, I moved toward his cell and peered into the window. I saw Mr. Jackson there, tattoos covering his face, anger in his eyes, and nothing in his cell.

In an anguished voice, he told me what happened. Yesterday, he had lived in the cell next to Mr. Waylen, and when Mr. Waylen reached through his pie flap and threw something into Mr. Jackson’s cell, Mr. Jackson responded by throwing feces back at him. But these feces hit an officer instead. Mr. Jackson cried out to me, “I didn’t mean to hit the officer! I told him over and over, ‘I’m sorry!’ But they won’t listen to me! I can’t take it anymore!” He dropped to his bed, head in his hands, body shaking in anger.

My eyes scanned his cell. All his possessions had been taken in punishment. Nothing remained but a coarse blanket. The logic of retribution seemed to spread itself plainly before me: punish the wrongdoer, and when he reacts, punish him harder. This system takes angry, broken people and locks them in small rooms, alone, with very few possessions or constructive human contact, and then acts bewildered when these repressed humans snap. Offering no more than one hour of recreation time per day in a metal cage, serving food that could repel even the most famished dogs, and taking all one’s earthly possessions with each misdemeanor, our current system shames and provokes these men until they erupt. And when they do erupt, they are punished more.

Mr. Jackson could not take it anymore. His desperation almost broke me on the spot, and it took all I had to keep it together. Numerous times while listening to him, I had to ask him to pause because I could not hear him. The pod had descended into chaos. Men were horse-kicking their doors, shouting at each other and at COs. Some were throwing things. I felt consumed in noise. Even with my ear pressed to the door and Mr. Jackson shouting on the other side, I could barely hear him. Inmates shouted obscenities at COs; COs shouted back, taunting the inmates to cut themselves. They seemed ready to oblige, as shirts flew off and razors appeared.

Promising Mr. Jackson I would bring him a book to read to keep his mind occupied until the staff returned his property, I moved swiftly around the pod, trying to deescalate. I felt I had no idea what I was supposed to do. I was just making it up as I went. But one by one, the men grew quieter and their razors disappeared.

I headed out of Unit 4 and walked back to the chaplain’s office to get books for Mr. Jackson. At the chaplain’s office, Chaplain Alexander was rushing out the door to catch the ambulance that was ferrying Mr. Saylor to the hospital. He was fading. She called me from the ambulance and told me that he might die.

When I arrived at the prison chapel that evening, the Friday night service had begun. I slipped in quietly to a pew against a side wall. Chaplain Alexander sat just in front of me. When she saw me sit down, she reached back and squeezed my hand, whispering that Mr. Saylor was stable. Just a few minutes later, I slipped back out, crouched in a corner of the hall, and wept.

I had never seen scars like Sam’s, and I never want to again. It was my third encounter with him, having first met him while making rounds in the mental health pod of Unit 4. In our first two visits, tears filled his eyes, attesting to his emotional exhaustion as he vented his weariness of years of solitary confinement. In both visits, I found Sam to be kind, gentle, vulnerable, and emotional. The third time I visited his cell, however, he was different.

From the opening exchange, I knew Sam was angry. His agitation produced a visible physical tension. I tried to assume a positive but concerned demeanor.

“What’s going on with you today, Sam?” I inquired.

“I’m about to lose it,” he replied with confidence. He then spoke of turmoil in the pod, detailing the destructive dynamics between correctional officers and inmates. “I’m about ready to start terrorizin’ again,” he said.

This language disturbed me, and I asked him to explain. Sam’s descriptions horrified me: “I take control of my pie flap. I tell them get the fuck off my door. If they don’t, I might pull their arm through the pie flap and break it. Maybe cut off a finger with a razor. Sometimes I throw homemade pepper water in their eyes. Maybe some shit and piss.” He made this list matter-of-factly and without hesitation, but his tone suggested slight apprehension, as if in this vulnerability he feared my rejection. I dug deeper.

“Why do you want to do that? Do you feel it accomplishes your goals?”

“They fear me,” Sam said, his eyes widening. “They learn real quick not to mess with me.” We conversed back and forth about this, as I realized more fully the violent past and potential of the man on the other side of the steel door – a man who, as a five-year old, had to help his mother roll up the body of the dead pimp lying on their carpet; a man who had witnessed women sell their young daughters, as well as their own bodies, to drug lords for $20 worth of crack cocaine.

I suddenly noticed what I thought was a rash on his lower neck. “What happened to your neck there, Sam?” I asked, trying to lighten the conversation. I had no idea what revelation that question was about to produce. Sam smiled, and without saying a word, removed his shirt. It was then I saw the scars on his chest.

Sam stepped back from the door so I could see his entire torso. His fit upper body was almost fully covered in interwoven scars, documenting a pattern of extensive self-violence. Numerous uninterrupted scars ran parallel from either shoulder to the opposite hip, crisscrossing in the middle. The scars rose out from his flesh, some as far as an inch. Clearly, he had cut deep and often. Innumerable scars tattooed both arms. Almost no inch of his upper body had escaped his attacks.

“See, I’ve been cuttin’ a long time. A lot of these guys, they cut short. They don’t go deep. They can’t. Can’t take the pain. Me – I’m all in. When I cut, I rip through,” and he demonstrated this ripping, pulling his right hand across his chest with brute force.

“Why do you cut like that?” I asked with soft voice and sapped energy.

“Sometimes the situation here is too much. I can’t stand it. I cut like this so I black out. At least in those moments, I don’t have to deal with this place. Some days I just wanna end it all – ya know, black out and not come back.” He leaned his head back slightly as a tear slipped down his cheek, and it was then I noticed his neck again.

With his shirt off, I could more clearly see the markings on his neck. They too were razor scars. He then told me how he had sliced deep into his neck at least three times in suicide attempts. His flesh was wrinkled and ragged from layers of scar tissue that formed a complete circle around his neck. As my eyes scanned his whole body, I saw far too much mutilation.

It was now uncomfortably clear that Sam had a painful story to tell. His past must be filled with the same sort of violence I saw displayed on his dark skin. Before moving on to the next cell, I paused and leaned against the wall. I needed a moment to process. I had never seen a body more marred than his. I wondered how such a place could exist, a place so violent and dehumanizing that someone would prefer to die or blackout from self-mutilation than face another moment incarcerated.

I closed my eyes, breathed deeply, and stepped in front of the next cell. Feigning positivity, I greeted, “Hey Mr. Bedford, how are you?”

God, where were you today? Perhaps you too were weeping, crouched in the corner of your hallway, and could not get up. Perhaps you too choked on your tears and could not raise your voice. To know you also can be so shocked by our horribleness to each other that you cannot speak, to know that you also can be so traumatized that you must stop to weep, would give me some manner of peace.

Jesus, you said that when we encountered the least of these in prison, we encountered you. I try to believe that. But was that really you in there? Was that really you the officers carried out of the unit to the ambulance? I didn’t expect you to look like Mr. Saylor, smearing blood on his face while I talked with him. O Christ, who suffered mutilation at the hands of others, your body must have looked much like Sam’s. Your scarred flesh must have horrified others the way his horrified me.

I knew you would be in prison, Lord. That’s why I came. But I didn’t realize you would be in hell.

Michael McRay

Michael McRay

Michael T. McRay is a writer, adjunct professor, and storyteller. This piece is adapted from his new book Where the River Bends: Considering Forgiveness in the Lives of Prisoners (Cascade, 2016). He works at the Tennessee Justice Center in Nashville, co-founded No Exceptions Prison Collective, and founded and co-hosts Tenx9 Nashville Storytelling.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Tammy Jane

This is filled with so much pain, it hurts. You've such a beautiful way of sharing something terrible and dark. Thank you for doing this work.