Subtotal: $

Checkout-

What’s the Good of a School?

-

On Praying for Your Children

-

The World Is Your Classroom

-

The Good Reader

-

Kindergarten

-

Should Christians Abandon Public Schools?

-

Why I Homeschool

-

The Children of Pyongyang

-

How Far Does Forgiveness Reach?

-

Michael and Margaretha Sattler

-

The Pen and the Keyboard

-

My Fearless Future

-

Covering the Cover: School for Life

-

The Community of Education

-

Family and Friends: Issue 19

-

Verena Arnold

-

Tundra Swans

A Debt to Education

Universities can shape their students for life – in more ways than one.

By John Thornton Jr.

December 31, 2018

As universities never tire of pointing out, education is more than the mere transmission of knowledge. It is about formation. Professors and administrators all impressed this upon me often during my years as an undergraduate and later at seminary. At Baylor, a Baptist institution, this took the form of weekly chapel services and university-sponsored mission trips. At Duke Divinity School, students gathered regularly in “spiritual formation groups.” Formation at both institutions meant not just studying but developing habits, disciplining desires, and living in a community of supportive people in order to foster a particular character.

It worked. My university studies made me who I am by shaping how I approach not only my pastoral work but also politics, economics, race, gender, sexuality, and society.

Yet my university experiences also formed me in other, less obvious ways. They made me into a person whose life choices – from which job to take, to how many children to have – are in large part determined by my student debts.

We don’t often talk of the formative nature of debt in the same way we do in regard to other educational experiences. But just as education is about more than funneling information into students’ brains, indebtedness is about more than the transfer of money. Universities rarely address the aspect of higher education that may most powerfully shape students’ futures: the debt they take on to finance it.

A few hours spent watching promotional videos for universities, whether public or private, illustrates the point. These commercials display a remarkable consistency. Wide shots of buildings chosen to match what prospective students presumably imagine a campus to look like; a montage of student athletes competing; an articulate voiceover offering an inspiring narration about students finding themselves. There’s always an image of teenagers studying in a library. In these commercials, almost without exception, universities tout the difference that their graduates make in the world. They rarely mention future earnings.

Visually, they relay this message of empowerment by including as many scenes outside the classroom as inside. They convince students that university education serves not just to help them get a leg up in the market, but to shape them into particular kinds of people for the sake of a common future. In the words of the University of Alabama website, this goal is an education that “produces socially-conscious, ethical and well-rounded leaders who are grounded in their subject matter and capable of controlling their own destinies.”

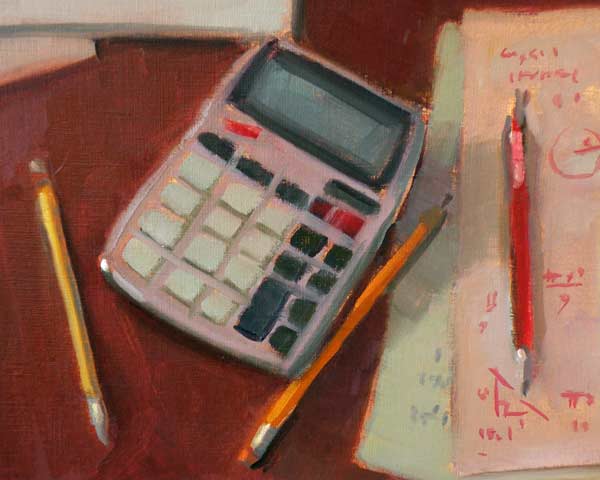

Margaret McWethy, Jif. Images reproduced by permission from Margaret McWethy

It’s a grand vision that echoes a tradition stretching back to Plato. However, those espousing it rarely seem to reckon with the possibility that students’ debts might prohibit them from ever being “capable of controlling their own destinies.”

Debt forms us just as radically as a university curriculum does. As bills mount, debt becomes a guiding force in our lives, directing our decisions about where to live, where to work, how to save and spend, and what we imagine possible. The anxiety, regret, and shame over one’s inability to determine one’s own life shapes our souls as well. In a deeply moving essay in The Baffler, M. H. Miller describes his working-class family’s struggles with the $120,000 in debt they assumed to enable him to attend New York University: “The delicate balancing act my family and I perform in order to make a payment each month has become the organizing principle of our lives.” If student debt forms us in this way, we’d do well to ask what kind of formation it is.

Student debt occupies a prominent place in the US economy. In 2018, Americans carried $1.5 trillion in student loan debt. The average 2016 graduate had $37,000 in loans. Forty-four million Americans have student loans, meaning roughly one quarter of the population is shaped and formed by the monthly payment they must make.

All debt forms us, but it’s important to recognize how student debt shapes our conception of ourselves and our society.

All debt forms us, but it’s important to recognize how student debt shapes our conception of ourselves and our society in a way different than other ways one can owe money. Credit card debt or payday loans, for example, often result from emergencies. Car loans are a rent for needed transportation. We can leverage mortgage debt for wealth building. For all our grand visions of education and formation, when it comes to finances we usually talk about how student loans enable a borrower to attain a professional qualification that moves them into a higher income bracket. In a capitalist society in which every choice requires a financial calculation, looking at student debt as a matter of calculated choices forms us in distinct ways that warrant our attention.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

The Retributive View

One way of framing indebtedness as an individual choice is retributive. It looks backward to the past: students could have made different choices to avoid or mitigate their debt. They could have chosen majors that pay more or schools with higher rates of success in the market. They could have worked a second or third job. They could have eaten ramen at home instead of going out.

Because of all this, people with the retributive view don’t believe debtors worthy of grace. Adopting the retributive view conveniently gets them off the hook for any obligation they might have toward those in debt. The debtors could have chosen otherwise.

Take my own case. I didn’t have to go to Duke Divinity School. I could have chosen a more affordable seminary (plenty of pastors complete an online degree); I could have worked harder and gotten better grades, and so earned more scholarships; I could have put more hours into part-time jobs. To the last point, one semester during my studies I worked two late night shifts a week at a coffee shop on campus in addition to the twenty hours I worked tutoring middle school students. After a few weeks I decided that the extra $75 I earned wasn’t worth the exhaustion I felt in class the next day. Of course, I could’ve chosen to stick with it and knocked a few hundred dollars off the $47,000 debt I graduated with.

I recognize my own privilege in this scenario. Millions of people deal with far more challenging circumstances, far deeper holes to climb out of. Almost all of my classmates did. I’m a relatively healthy single white male. These institutions were made by and for people like me. But they were also made to divide all of us in the name of consumer choice.

There’s a particular blindness involved in looking at student debt as a consumer choice. I remember one graduate school administrator expressing judgment that students complained about debt when so many of them paid for cable television. That year the average student graduated with $44,000 in loans. I struggle to imagine how choosing to forgo ESPN and HGTV would have made a significant difference, but that wasn’t the point. The point was the assignment of blame on students for failing to calculate the cost of their choices.

Margaret McWethy, What’s on the Table?

Bean counting aside, if we question the choice of going to a particular school or studying a particular subject, we also question the goods that came from those choices. Can we still love someone and say he should have gone to a different school from the one where he met his spouse? What about the person who discovered her calling to ministry at a particular school? Of course some people should have chosen otherwise, but when we reduce the basis of those choices to the strictly economic, we reduce people’s entire lives to a string of consumer choices. In doing so we accept an alienation – from ourselves and from each other – because education, like other goods, isn’t just one more consumer choice.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

The Redemptive View

This retributive view with its emphasis on regret often clears the way for another way of framing consumer choice, one that promises redemptive hope.

A few months ago the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship awarded grants of $10,000 each to me and about a dozen other ministers so we could pay off debt. Having determined that debt plays an important, damaging role in the lives of ministers, CBF’s Ministerial Excellence Initiative combines immediate financial relief with two gatherings to discuss finances and ministry, and a year of financial advising. The first session was a kind of crash course in basic financial literacy, similar to that taught by Dave Ramsey. Over the two days of the training, we consistently heard two messages. First, we ought not to lose sleep over finding ourselves in debt. We shouldn’t feel guilty about the underwater mortgage, the unexpected pregnancy, the student debt for seminary. All of the ministers spoke with refreshing candor about how their financial struggles affected their ministerial work. All of us admitted to living with a loneliness brought on by believing that we couldn’t publicly discuss our personal finances for fear of appearing ungrateful. I’ve heard my fair share of retributive cruelty about my indebtedness, so I found the words of grace spoken by the instructors and ministers remarkably refreshing.

However, I noticed that choice and guilt came back in when we talked about the future. The second message we heard repeatedly was that though significant unavoidable decisions in the past got us into debt, a myriad of small ones in the future could accumulate to get us out. Like most financial literacy trainers, the instructors pinpointed discreet purchases as the way to save money and get out of debt. They never said it quite so plainly, but I heard that we ought to feel guilty when choosing wants over needs in our future consumer spending. Repeatedly the trainer used the example of eating peanut butter at home versus Mexican food at a restaurant. So while I shouldn’t feel bad about choosing Duke over a more affordable seminary, I deserve the consequences of choosing La Hacienda over Jif. In a conversation we spoke at length about how we all needed to purchase cheaper toilet paper. No one brought up the possibility of increased medical bills brought on by eating exclusively peanut butter, but it seemed to me like something we ought to consider when calculating expected future expenses.

I noticed that choice and guilt came back in when we talked about the future.

At one point I mentioned what seemed to be a rather obvious incongruity between the two messages. I made reference to the 2004 paper by Elizabeth Warren called “The Over-Consumption Myth,” in which she writes that American families spend roughly the same amount as previous generations on consumer goods. Spending on consumer goods has not driven people into debt. Rather, the rising costs of fixed goods like housing, healthcare, and education, combined with stagnant wages, have. In our training session, these statistics were dismissed: they troubled the narrative of redemptive choice.

Financial literacy is a kind of formation of its own. Such programs form us to believe that we can make up for one $40,000 decision with forty thousand other decisions that save a single dollar each. In retrospect, it seems fitting that Duke Divinity School required each of us to sit through a brief seminar on financial literacy prior to graduation. The school needed one last moment to shape us as individuals in control of our destiny through wise choices, hard work, and willpower.

Margaret McWethy, Chicken Noodle

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Demonization

Ultimately this formation of graduates as debtors-by-choice serves an important function within our political economy. It changes the problem of debt and higher education from one of collective, political responsibility to one of individual consumer decisions. And it completely ignores what role the broader political economic system plays in our indebtedness.

In his book Neoliberalism’s Demons, Adam Kotsko writes that the emphasis on individual responsibility in free-market capitalism bears a striking resemblance to the traditional Christian story of the origin of the devil and of demons. In order to explain evil in the world, this story – which, though ancient, is not found in the Bible – has been used to get God off the hook, so to speak, by blaming the devil. The logic runs like this: Why does evil exist? Because God made creatures with freedom of choice, and they’ve chosen to act sinfully. That God knew they would sin provides no reason to hold God responsible. God’s goodness remains intact while evil continues.

This economic theology of capitalism makes us the demons in the story.

Whatever the merits of this theodicy, it’s not hard to see how it parallels the way we give God-like status to capitalism in today’s economic cosmos. While we may acknowledge that market forces might influence a decision, we still hold consumers responsible for their individual choices and demand that they must bear the consequences. Capitalism can’t bear responsibility for the bad outcomes that happen in its system, just as, according to Christian belief, God retains God’s goodness in the face of evil.

This economic theology of capitalism makes us the demons in the story, the ones to blame when things go wrong. Think, for instance, of the common idea that individual recycling can stave off climate change – this in spite of the fact that one hundred companies produce 71 percent of carbon emissions. The political economic system and its most powerful actors remain in place while we scramble about arguing over one another’s plastic drinking straws.

Student debt is thus just one way in which the theology of capitalism “demonizes” people, especially the poor and those who belong to vulnerable minorities, by making them solely responsible for their misfortunes. It justifies the status quo by distracting from the political and economic forces beyond any one person’s control. Applied to the question of student debt, the logic of demonization says that while a college degree could lead to the benefits of increased income, it will very often bring too high a debt load. If it does, students should consider giving up the expensive degree and the debt it brings. If they do not, they rightly are to blame.

But that conclusion ignores a larger reality. A recently released paper by Julie Margetta Morgan and Marshall Steinbaum argues that “credentialization” – the need for higher degrees to get a better job – has driven up the cost of higher education and student debt. They discovered that while it’s true that those with a college degree still earn more than those without, this is because wages for those without degrees have gone down. Put another way, a higher degree provides a benefit but it does so because the potential risk of not attaining one has greatly increased. Going to college is no longer about moving up the ladder, but the only way to avoid falling down. The study’s authors find that this holds especially true for minorities.

Cathleen Rehfield, Stacked Cups Image reproduced by permission from Cathleen Rehfield.

Universities, facing their own financial crunch as public funding decreases, have added new degree programs eligible for available loan dollars. They know that students in need of yet another degree to remain competitive will enroll, making student loan dollars available to make up for decreased public funding. Morgan and Steinbaum write, “Colleges thus increase their revenue, since they know that demand will be forthcoming from students with no other option if they want to get a job.”

Student debt thus exposes a farther-reaching cruelty in a system that treats people, in the end, as autonomous consumers. Until we recognize the deeper problem, we will be hindered from taking collective action to build better lives together. We spend so much time blaming one another and ourselves that we don’t have time to look at bigger, collective solutions like tuition-free higher education or the cancellation of student loan debt. We don’t ask what kind of society we want to see and what kind of collective political action it might take to win it. Our eyes haven’t been trained to see society and its institutions as something we can change. Our imaginations haven’t been formed to desire something better fitted for human flourishing.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Counter-Formation

If economic failure is essentially a personal matter, then so is success. Flourishing would then be an individualistic, zero-sum game, not something gained and enjoyed together. That this lie seems plausible to so many is a symptom of the extent to which neoliberal habits have de-formed us.

Our eyes haven’t been trained to see society and its institutions as something we can change.

To remedy this, we need a kind of counter-formation. Any alternative, any resistance offered by Christians or others will require a community dedicated to the collective sharing of resources with the aim of achieving a world without interminable debt. For all its complicity in capitalism’s inhumanities, I can’t help but think that one such community should be the church: a community that lives in a way that accords better with the kingdom proclaimed by Jesus.

This counter-formation to combat the effects of capitalism would have to look a lot like what we see in university formation. It would have to reform desire, shape concrete action, and guide decision-making about how we use collective resources. Instead of treating people as isolated consumers, each individually responsible for her own fate, we need a theology that says we belong to one another. We must bear one another’s burdens, including our debts. We need a theology that preaches a freedom that’s more substantial than the freedom to earn and spend.

During the middle of our sessions on financial literacy, we took a break from discussing toilet paper and peanut butter and gathered in a circle. One by one, a member of each pastor’s congregation looked that pastor in the eye and described what he or she meant to their church. They told their pastors of their excitement for them to experience the financial freedom that the grant moved them toward. And one by one, they gave each a check for $10,000. We all shed a few tears, knowing the difference such an amount made. And in that moment each of us saw that we could do better. We could treat one another as human beings ought to – neither as reckless spenders deserving of retributive penalties, nor as “financially literate” spenders committed to years of penny-pinching.

We need a theology that says we belong to one another.

I think back to that moment, the one all of us would say powerfully moved us. I imagine what a community might look like that believed Jesus’ prayer for the forgiveness of debts “on earth as in heaven.” I think to myself what such a community of believers might do with its money, how they might use it to pay for the debts of others. I don’t see such a community here, but I can imagine it – and the mere ability to imagine this alternative world gives some measure of hope.

Another world is possible, a world without interminable debt. We can create a world together in which we are formed to see each other not as lonely individual consumers but as comrades creating a world of collectively shared goods. A different world lies waiting somewhere in the undetermined future, but we can’t build it individually. If we want to see it in our lifetimes, we’ll have to make it together.

Sign up for the Plough Weekly email

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Martin

A in CA and Rachel Rigolino both have excellent perspectives. Is there a way to synthesize their perspectives?

A in Ca

There are other ways student debt corrupts society by undermining the best intentions many young people have and encouraging inequality. A student with debt will, of course, have to consider it in his career choices: If school teacher, teaching in a poorly-paying district is out, better go for the suburban 'good' district, even when you started out, you thought you'd teach in an impoverished area. - Many law students do care about justice for all, but once they see the magnitude of their student loans, they realize they better go into corporate law, a work as a public defender (or in criminal court, or family court) or most government jobs don't pay [expletive] enough. So that's where many go, to corporate law, with the good intention to do 'pro bono' work. But there, too, is competition, and you don't have time for that. And by the time you are ready to do 'pro bono' work, you probably have a family, and a mortgage.... - Students wanting to go to medical school nowadays have to write essays on how they plan to serve 'underserved populations' and many sincerely write, that they want to help. Once the reality of student debt is recognized, it seems better to go for a high-paying specialty, and look for a job in a rich area, where the pay is better. Society would be better, if people could more easily follow their best intentions. Tuition at state colleges and universities should be free, and the cost be born by higher taxes on those who indeed become enormously successful (often by using a workforce, educated by state colleges). Many European countries can do this (tuition-free state universities), why not the U.S., which is richer?

A in Ca

Labeling the 'free-market' neo-liberal view of student debt as 'retributive' is fitting. This view, "It's your own fault, you should have gone to community college, taken a summer job, not have bought coffee" is still too wide-spread (even in these comments), and totally unrealistic. On any discussion of student loans, there will be someone saying, he went to Princeton in 1958, worked full-time every summer, and graduated without debt, on time. The fact is, there are no summer jobs any more, which in 3 month pay the whole year's tuition (not to mention rent + food) In fact, in our hyper-competitive environment, a student does better, if he/she concentrates on his/her studies and gets a better grade-point average, and more activities. Rachel R.'s comment points to one occasion where a scholarship was given to the student who tried to save money, rather the one with more activities due to having to work. Normally this would go the other way. After all, all graduate/professional school applications ask in great detail for activities, evidence of 'leadership', internships (often unpaid)... a student without enough entries there may have little chance.

seren

What a thoughtful and relevant essay. I have thought about many of these theories myself from a more secular point of view, I appreciated this greatly.

L

John Thornton, is wrong. All debt, does NOT form us. It is a means, to de-form us, by limiting our freedom, to create our own lives, as we go. This is why the powers-that-be ( = worldliness ), want us, to fall, under their sway Just because someone decides to blab, doesn't mean, that they deeply understand, anything. A person can only develop relevant understanding, through deeply questioning motives; benefits; & purposes, driving any incitement -- instigation, to launch, programmes Students, are a vulnerable group, so powers, of captivation, want, to get them, on board, as recruits, for mass opinion-forming ( - deforming ). Their misplaced sense of loyalty, is then, to serve, the turn, of the strategists, organizing the overall reigning world-reordering process The Lord, our God, truly hates, and condemns all this, as devilment. He is utterly opposed, to anyone taking advantage, of a person's fundamental dependencies. One must relate, to people, without any ulterior motives, for Him, to bless, and sustain us !

Michael Nacrelli

While structural issues need to be addressed, individual responsibility can't be entirely dismissed as Thornton seems to suggest. The simple fact is that many people's debt (student or otherwise) could be greatly reduced by choosing community college and foregoing luxuries such as cable TV, Netflix, mobile data plans, and eating out regularly.

Rachel Rigolino

Pastor Thornton's article reminded me of an experience I had several years ago when I sat on a small public university's scholarship committee. We did not have a lot of money to give away---I believe our largest award was only a few thousand dollars. Two young women were in the running for this award: the first lived at home, worked part-time, and commuted to school while the second lived on campus and was active in student groups that promoted social justice. At first, most of the committee wanted to give the award to the second student because she had devoted her time to volunteer work and also had accumulated more debt. I protested, noting that the first applicant could not be as involved with extra curricular activities because she worked and drove back and forth to campus. In terms of not amassing as much debt, she had chosen to forgo the residential college experience in order to save money. To my mind, the first student had made a great sacrifice upfront and deserved to be rewarded. In the end, we wound up dividing the award. I do not think I was viewing the second student through a retributive lens; rather, I wanted the first young woman to know that her "bean counting," as Pastor Thornton puts it--and the subsequent sacrifices that go along with such austerity--deserved recognition.