Subtotal: $

Checkout

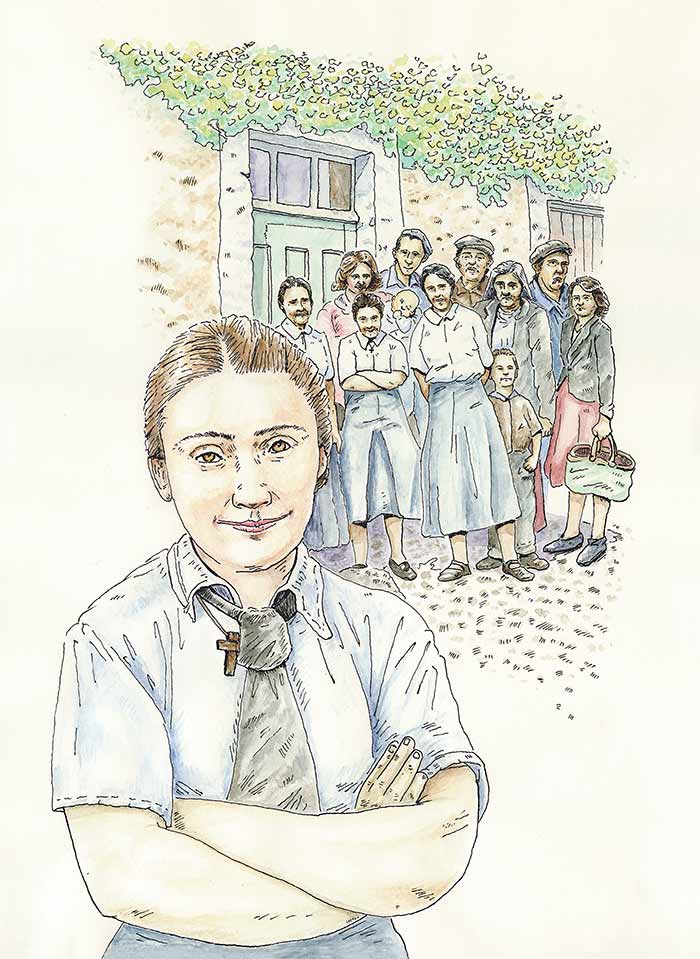

In 1933, twenty-nine-year-old Madeleine Delbrêlmoved with two friends to a house in Ivry-sur-Seine, a Paris suburb that was then a hotbed of Communism. They vowed themselves to a life of simplicity, chastity, and evangelism. Their plan was, simply, to love their neighbors – personally, affectionately, practically. She worked as a writer and lecturer, and sought every day to respond to those whom God set before her to love and serve.

On the streets of Ivry, Christians and Communists clashed openly, but the Delbrêl house had an open door, a place of hospitality where anyone from any background would be welcomed and accepted: “a tiny cell of the Church,” Delbrêl wrote, “born in our time, making its home in our time.”

She had not been raised as a Christian; her parents were fashionable agnostics. At seventeen, she wrote a manifesto beginning, “God is dead. … Long live death!” The Delbrêls held lavish parties; Madeleine entertained guests with readings. She studied philosophy at the Sorbonne, designed her own clothing, and cut her hair short. She became engaged to a philosopher, another atheist.

Then things fell apart. Her parents became estranged, and her fiancé broke off the engagement to join a Dominican order. Shattered, Madeleine’s thoughts returned to the God question. “I met several Christians,” she wrote, “neither older nor dumber nor more idealistic than I was; in other words, they lived the same life I did, they discussed as much as I did, they danced as much as I did.”

And then, “I decided to pray. … By reading and reflecting, I found God; but by praying, I believed God found me and that he is living reality, and that we can love him the way we love a person.”

Her conversion was conclusive – “bedazzling,” in her words – and, from the age of twenty until the day she died, she never ceased being “overwhelmed by God.”

Though she now rejected the Marxist material analysis of the world, she refused to reject the Communists themselves. “If there are Christian women whose husbands or children … are Communists,” she wrote, “they love them with a love God makes his own. To love them, they don’t have to accept the Party card that declares their opposition to God. … But by refusing their card, these women aren’t required to deny their flesh, their heart, their affection.”

Madeleine Delbrêl died working at her desk in Ivry-sur-Seine on October 13, 1964, from a brain hemorrhage; it was two weeks before her sixtieth birthday. In 2018, Pope Francis declared her “venerable,” putting her on the path toward canonization as a saint.

“There are some people,” she once wrote, “whom God takes and sets apart. There are others he leaves among the crowd, people he does not ‘withdraw from the world. …’ They love the door that opens onto the street. … We, the ordinary people of the streets, believe with all our might that this street, this world, where God has placed us, is our place of holiness.”

Artwork by Jason Landsel

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.