Subtotal: $

Checkout

Wendell Berry’s Long Obedience

A lover of place pushes against the unraveling of America.

By Gracy Olmstead

August 2, 2021

Humans have long reverenced the world around us through words. Native American scientist and professor Robin Wall Kimmerer writes in Braiding Sweetgrass that Nanabozho – the Original Man, according to legends of her people – was instructed to learn the names of all living things, and thus found a balm for his loneliness. In the biblical story of Adam and Eve, God instructs Adam, the first man, to name all the animals: “the Lord God formed every animal of the field and every bird of the air, and brought them to the man to see what he would call them; and whatever the man called every living creature, that was its name” (Genesis 2:19).

Our sense of being and identity is formed by our perception and understanding of where we are, by the way we name the world and ourselves. But many modern humans lack a full understanding of their places, and of their identities as placed within that landscape – they are, in Dr. Norman Wirzba’s words, “wayward”: lacking an understanding of where or who they are.

Not so with Wendell Berry, writer and farmer, whom I first met five years ago. He is a lover of place, who has done the hard work of living in place for a lifetime. He does not just write down his convictions – he lives them, with consistency and devotion.

“Instead of being at odds with his conscience, he is at odds with his times,” David Skinner said of Berry at the time of his 2012 Jefferson Lecture. “Cheerful in dissent, he writes to document and defend what is being lost to the forces of modernization, and to explain how he lives and what he thinks. He is the sum of his beliefs.”

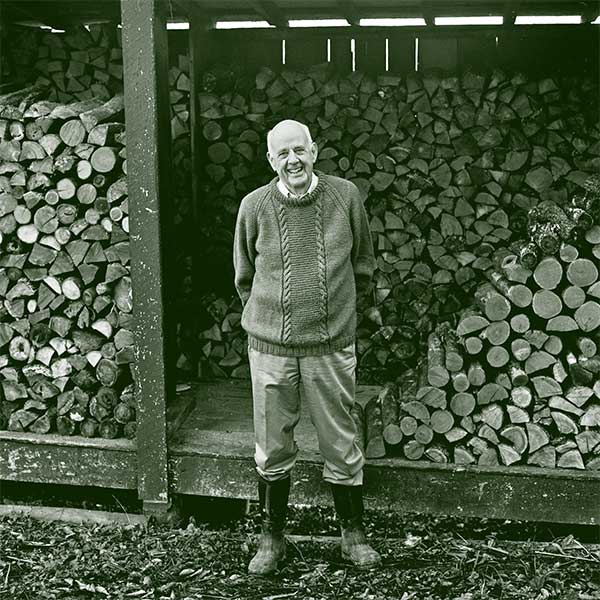

Wendell Berry, 2019 Photograph by Guy Mendes

Wendell Erdman Berry was born in 1934 to John Marshall Berry and Virginia Erdman Berry. He grew up in Henry County, Kentucky, where his father worked as a lawyer and tobacco farmer. Both his parents were avid readers and instilled in their children a love of words. But the Berrys were also stewards of place and passionate advocates for their local farming community. Instead of becoming a “big-city lawyer,” as Skinner puts it, John Berry decided to return to Kentucky after law school. There, he served as a state senator from 1973 to 1982, and was the general counsel and the president for the local Burley Tobacco Growers Cooperative Association for many years. He advocated for numerous things his son would go on to champion in his own work.

Wendell earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees at the University of Kentucky in Lexington. He met Tanya Amyx while at school, and the couple married in 1957. The following year, Berry attended Stanford University’s creative writing program as a Wallace Stegner Fellow. His first novel, Nathan Coulter, was published two years later. Its pages reveal Berry’s love of place, and demonstrate his yearning for it, even as Berry describes the lust for “elsewhere” which captivates so many.

“Uncle Burley said hills always looked blue when you were far away from them,” Berry’s protagonist, Nathan, notes in the book’s opening pages. “It made you want to be close to them. But he said that when you got close they were like the hills you’d left, and when you looked back your own hills were blue and you wanted to go back again. He said he reckoned a man could wear himself out going back and forth.”

In 1961 Berry received a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship, which led him to visit France and Italy with his family for a year. Upon their return to the United States, Berry began teaching English at New York University. He had “gone far,” both figuratively and literally.

But Berry didn’t want to go far. He wanted to go back. In 1964 the family returned to Kentucky with their two children and Berry began teaching creative writing at the University of Kentucky. The couple bought Lanes Landing Farm, near where he had grown up, which they used as a summer place. In 1977, Berry resigned from his university position, and Lanes Landing Farm became home. The farm’s surrounding Port Royal community served as the focus and inspiration for Berry’s work.

In all of his writings – the numerous novels, poems, essays, and short stories Berry has written since 1960 – it is Lanes Landing and Port Royal that provide the rich texture to the page. Though Berry returned to work at the University of Kentucky’s English Department from 1987 to 1993, he never left the farm for long.

Berry’s fellowship with Stegner, as well as his Guggenheim fellowship and New York University teaching position, hint at the possibility of a more cosmopolitan life – one more focused on his own ambition than on the humble voices of rural Kentucky. So why did Berry choose Port Royal – and keep choosing it?

“I just happen to have no appetite for glitz and glamour,” Berry explained in a 2008 interview with The Sun Magazine. “I like it here. This place has furnished its quota of people who’ve helped each other, cared for each other, and tried to be fair. I have known some of them, living and dead, whom I’ve loved deeply, and being here reminds me of them.”

For Berry, ambition and talent are inseparable from his deeper fealty to family, place, and community. Where many of us have a markedly individualistic vision – in which talent and dreams carry the self beyond a local scope – Berry lives in a world in which young and old, nature and farmer, individual and community are all woven together in a thick tapestry. It is an indivisible network, and Berry has embraced its limitations alongside its many gifts. Regardless of how Berry came to receive this vision, he has most certainly called it forth in thousands more hearts – including mine.

When we first met, at a conference in Louisville, Berry was the keynote speaker, but he and Tanya arrived several hours early, and he took notes during the panels and lectures before and after his speech. Afterward, when I asked Berry whether he might be willing to do a Q&A with me for The American Conservative, he agreed, but on the condition that the interview take place via letters, rather than by phone or email. Thus began a correspondence that, remarkably, has continued (off and on) to the present day.

After the first piece was finished, I wrote down some memories of growing up in rural Idaho, of my farmer grandpa and great-grandpa, and shared them with Berry. He encouraged me to make these memories the focus of my agricultural writing. “When you write about family farming, do it always from your family’s point of view, and your own as a member of your family,” he suggested.

I have come to see that quiet lives on the land are just as important as any politician’s or celebrity’s life, yet they are usually unsung and unnoticed – often fading into the earth without any, except family, to remember them or write them down. To write about the “nobodies” of rural America is to keep alive the names that provide meaning, intimacy, and beauty to our world.

Over the past decades, Berry has written more than fifty works of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. He has received a National Humanities Medal and the Richard C. Holbrooke Distinguished Achievement Award, given for works that “advance peace through literature.” His literary legacy is one of the most important in American history – but also one of the most personal and particularized, one might argue.

By loving Henry County, learning and preserving its names and voices, Wendell Berry inspired the world. A single grain of wheat embedded in the earth can bring forth much fruit. He has argued against the consumerism which pushes us to spend, rather than to conserve and create. He has fought the industrialism which has fostered environmental degradation. And he has given us visions of place well-tended, pushing against the unraveling of community across America.

“People exploit what they have merely concluded to be of value, but they defend what they love,” Berry argues in his essay “On Edward O. Wilson’s Consilience.” “And to defend what we love we need a particularizing language, for we love what we particularly know.”

In that first Q&A we did, I asked Berry whether his protagonist Jayber Crow (of the novel of the same name) was a “conservative.”

“His membership is not in a party or a public movement, but in Port William,” Berry replied. “He is a man of unsteady faith in love with a place, a perishing little town, a community, a woman – with all that is redemptive and good – struggling to be worthy.”

Naming is meant to be an exercise that grows intimacy and relationship, that helps us to truly see. Yet political labels – with all their tendency toward stereotype, generalities, and partisanship – are names that increasingly seem inclined to distance us from each other, and to distract from the nuances of our particular, local lived experience. Thus Jayber, rather than being a “conservative,” seeks to conserve and love Port William. In a later letter, Berry suggested to me that I (like Jayber) could be conservative, in an adjectival sense – cognizant of things worth conserving, and eager to conserve them – without being a conservative.

“I hope you can keep the adjective and evade the noun,” he wrote. In the years since he offered me this advice – years that have been politically fraught, troubling, and divisive – I’ve increasingly leaned on the wisdom of his words. And I’m grateful to him for choosing Henry County, for giving himself to it, forsaking the allure of far-off hills in order to love the corner of the world he’d been given. In doing so, he charted a path that many of us now seek to follow.

In his book of Sabbath Poems, Berry offers meditations on the same place, taking in its growth and aging, even as he himself matures and changes. The below poem strikes me as a set of instructions for the “wayward,” who want to follow in Berry’s footsteps – to study and know their own places, wherever they might be.

Because we have not made our lives to fit

our places, the forests are ruined, the fields eroded,

the streams polluted, the mountains overturned. Hope

then to belong to your place by your own knowledge

of what it is that no other place is, and by

your caring for it as you care for no other place, this

place that you belong to though it is not yours,

for it was from the beginning and will be to the end. …

Speak to your fellow humans as your place

has taught you to speak, as it has spoken to you.

Speak its dialect as your old compatriots spoke it

Before they had heard a radio. Speak

Publicly what cannot be taught or learned in public.

Listen privately, silently to the voices that rise up

From the pages of books and from your own heart.

Be still and listen to the voices that belong

To the streambanks and the trees and the open fields.

There are songs and sayings that belong to this place,

By which it speaks for itself and no other.

2007, Poem VI

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Terry Lovelette

Thank you for this wonderful article. It evokes feelings of connection and gratitude to one’s place in the world. Mr. Berry writes from a place of his deeper truth pulled from his interconnected world. Certainly an experience unique to him, but relatable to anyone who’s perspective is similar. I suppose it’s easy to see this unless it isn’t. In my humble opinion, Ms. Olmstead does a superb job of presenting us with an honest take on one man’s perspective while sharing some of her own. Both resonate with me. It comes with more breadth and depth than the banal discourse that rules the airways in today’s world. Yet, life is a process, not an event. Shifting seasons occur. I suppose that it’s up to the individual to pay attention, or not… Well done! A time of transition In the woods leaves lay to rest in a carpet of color Shifting seasons A time of transition In silence the way of nature keeps pace with the cosmic flow Running within a cycle of creation Living, dying, and rebirth happening as it does Without the slightest care of public opinion Whitman’s test of wisdom Felt in the depths Unable to be passed on A certainty of the reality and immortality of things Held in excellence Offered in the float of sight Brought into the senses Under the clear blue sky and the spacious clouds It prospers in the landscape Flowing currents of the divine Provoking a response From the deepest regions of the soul It lingers in its place Patiently in search of someone to pay attention

Theresa Byer

I thank you for this heart touching article. It spoke volumes to me this early morn' here at our sweet cottage. Devotions are my time with my heavenly Father. He gifted me your words. Thank you. 💕🙏💕

Tom Crotty

In response to Daniel--Mr. Berry would do better, but as someone who is a fan of Mr. Berry's work, with roots in Kentucky, working with my uncle and cousins a couple of years when I was in my 20's doing the hard, hand labor of growing and harvesting burley tobacco, I'll try. From pulling the tobacco plants from beds, then setting or planting them in the field, hoeing the rows then topping the plants so they become full, then cutting the stalks in steamy August weather to then house or hang in the barn for curing, to be taken down in the winter months and stripped by hand, each leaf from each stalk, this was and only could be a communal effort. It was a way inherited from generations that helped small family farms like my uncle's survive, providing much needed cash to help pay expenses year by year. This work depended on families, communities coming together to get the work done, and as naturally happens in such circumstances, cultures and traditions developed across the generations---what Berry would call the truest form of agri-culture. I think it was the community, the culture that Berry loved and respected, not the product. Field crops like soy and corn are owned by the agri-businesses with big machines working huge plots of land. Burley tobacco, at least as I knew it, was never more than 8 or so acres, as much as 3 or 4 with help at harvest time could manage. I fondly remember the camaraderie, the pleasure of the fellowship that emerged in sharing the backbreaking work. That way of life, those communities, are largely gone (See Tobacco Harvest: An Elegy). That the loss of life attributed to tobacco use is much reduced is cause for celebration--that a culture and way of life that sustained small rural communities in Kentucky has been replaced by an exodus of young people to the cities and the scourge of opiods for many who stay is cause for grief and alarm.

Michele Morin

I return to Wendell Berry’s work as if Jayber were my eccentric uncle, needing to be looked in on, and Hannah Coulter my fictional, wise mentor.

Daniel Coleman

I’ve read several of his poems and at least one novel by Wendell Berry. I’ve enjoyed what I’ve read, but it’s hard for me to get past what I see as a contradiction between what he writes and the fact that he’s a tobacco farmer. I know little of farming, but couldn’t he grow soy beans?—or anything that would cause less harm. So, although I recommend at least one of his poems to all my friends (“The Mad Farmer Liberation Front”), I nonetheless live with contradictory feelings about him. I haven’t read anything by him or any of his fans that address this issue. Any thoughts?

Helen Tester

Wendell Berry has been an inspiration to me over the years. How nice to see him afresh through this piece. Thank you…