Subtotal: $

Checkout

Remove the Graveclothes

How does the Easter story change the way we remember the dead?

By Nicholas Allmaier

May 19, 2023

The one who had died came forward, with hands and feet bound in strips of linen, and face wrapped around in cloth. Jesus said to them, “Remove the graveclothes and let him go.” —John 11:44

It was only when Joseph had established himself in Egypt as an advisor to Pharoah that he married and had children. He named his first son Manasseh, from a word for forgetting, saying, “It is because God has made me forget all my trouble and all my father’s house.” Yet this name must be in some way ironic. How, after, all, would Joseph even think to name his son “forgetting” if he had truly forgotten the problems of his childhood home?

Rather, the name may be read as an aspiration. Joseph wishes to forget. Sold into slavery by his brothers in his youth, Joseph is someone concerned with self-mastery. To be able to forget even his own roots and would confirm him as a self-made man.

But Joseph, despite his wishes, is not self-made. Seemingly just as soon as his sons are born, a famine in Canaan drives his Hebrew brothers to visit Egypt in search of food. Upon seeing them, Joseph is overcome with emotion. When his brothers return to Egypt a second time, Joseph sees his only full-brother, Benjamin, for the first time in many years. For Joseph, Benjamin must be an embodied reminder of their late mother, Rachel. When Joseph saw him alive and before him, he fled to his room and wept alone.

Joseph’s tears are ambiguous. He has many reasons to weep: relief at seeing his brothers, lingering resentment over his treatment, a new hope of reunion, the realization that he indeed has an origin and is not truly self-made, the memory of his beloved mother. His story is one of a process of gradual and painful self-understanding marked with outbursts of long-suppressed love, culminating in tearful self-revelation and reconciliation.

Maybe the living take up too much room and the dead too little when memory rather than hope guides reflection.

In his essay “The Work of Love in Recollecting One Who Is Dead,” Søren Kierkegaard recommends weeping for the dead, although not in the manner Joseph did. “I know of no better way to describe true recollection,” he wrote, “than by this soft weeping that does not burst into sobs at one moment – and soon subsides. No, we are to recollect the dead, weep softly, but weep long.” We do not know when we are to reunite with the dead, says Kierkegaard, and long mourning is a testimony not only to this harsh uncertainty but to the love we have for them.

At Easter, however, we can recollect the dead in a different spirit. The hope of the resurrection is that the dead may, like Benjamin to Joseph, return to us from a great distance. With confidence we hope to see and know them again – to see them reborn.

It was a happy coincidence, then, that my late mother’s birthday fell on Easter this year. I was a child of twelve when she passed away, and I have now lived more of my life without her than with her. The distance is great. The concurrence of these two days presents a fitting occasion to try to remember her.

But this task isn’t simple. Kierkegaard compares recollecting the dead to dancing a couple’s dance alone, or having a conversation with no one. One half of the relationship is missing. In this way, remembering the dead also leads us to test and learn about ourselves in light of the love we bear for those who have passed. And if I were to know myself even a little better on account of my mother, I think she would not blame me for it. So I will attempt a remembrance of her now in order to avoid Joseph’s error, in order to love her and understand myself.

My mother was a scientist. She studied for a master’s degree in animal science after college. Her adviser tasked her with field work, watching over bird eggs as they hatched, then studying the chicks as they grew. To get the clearest picture of their development, she was told, she would have to select a few, euthanize them, and perform autopsies as a part of her research. The thought of this destruction struck her as so disagreeable that she quit the program. She never performed the experiment.

After this she became a food scientist, following her father, but continued throughout her life with her love for and fascination with animals. Her tenderness for animals is something everyone remembers. But her care was not limited to animals; it did not issue, as it sometimes does, from an antipathy toward people. It was rather a meaningful echo of the love she had for them.

This love enjoyed its most evident testimony at her funeral, where so many mourners arrived that the room was overflowing. Teachers and neighbors, family and friends, and even the local mailman for whom she left an annual Christmas gift in our mailbox eulogized and remembered her. While the priest commended her motherhood, I recall staring at a sculpture of Saint Anne teaching Mary how to read. And I remember turning around to see many faces turned toward me, all marked by an acute mixture of grief and love.

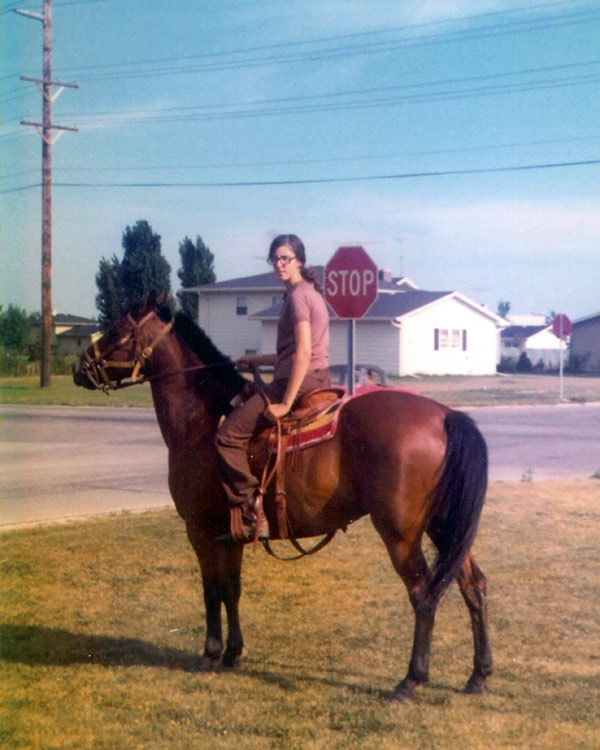

The author’s mother with her father's horse, “Bucky.” Photographs courtesy of the author.

Among those faces were those of my grandparents, aunts, and uncles. She was close with them all, and we visited them every Saturday. She especially loved my grandfather, and I can remember watching them attend to horses together as a child. In their relationship I saw for the first time what might be called the strange connection between love and law. To honor one’s mother and father is part of the law, but for her there was no need of compulsion or command for this. In behavior like this, she imparted a kind of education to me, which has supplied me with many of the questions I still pursue as a PhD student in philosophy. She is, in some way, with me when I think.

Her siblings still recall that when their own grandmother died, she, being the eldest of the six, comforted them with assurances about heaven and God’s love. But she was with them in moments of joy as well as sorrow. She was playful. As a college student she took to leaving gifts around the house for her youngest sister to discover, and as a mother she would play games of imagination with me. I have many memories of when, driving past a river in our town, she would ask me, “Nick, what do you see in there?” I would reply with different animals, escalating the ridiculous character of the scene with each new addition, to which, without fail, she would reply: “Uh oh! We should get out of here, quick!” Her absence is still palpable, but not without the love that accompanies honest and persisting grief. In my grandparents’ house there is a small corner where they have placed photos of and keepsakes from her. I keep her bible on my desk.

There are strange omissions in my sparse but vivid memories of her. I remember her laugh, but I cannot remember her voice. I recall her taking me to art shows, gardens, science fairs, but most of these memories are composed of fragmented images, actions or moods, only occasionally containing our conversations or her remarks. One discussion I do remember clearly came when I returned home from school one day and told her I had been convinced by classmates of mine that God does not exist. After some debate she calmly looked at me and asked, “Would you rather believe men or God?”

All of this is pleasant and worthy of remembrance, and I could continue in this way at length. But this sort of eulogizing seems insufficient for what I am trying to do. Recollecting the dead in love seems to me to be difficult for this reason: when I remember my mother, I cannot help but through this activity to mix myself so thoroughly with her that I can hardly distinguish between us. This is not the same blending Montaigne wrote about in remembering his friend Etienne, with whom he felt he shared a unity of soul; nor is it that harmony which Augustine describes with sorrow when he says he and his mother, Monica, shared one life, torn apart finally in death. Rather, it is more akin to the relationship of a painter whose subject has long left the room. With half remembered stories and blurry childhood memories mingling with my own tastes, desires, and hopes, I retouch her portrait each time I try to behold it. By making an image of her I risk, gradually and unwittingly, only making one of myself.

It is true that this may help me to know myself, to understand what I care about, how I see the world, as revealed in my recollection of her. But there is a risk here, I think, of not only becoming more sentimental and indulgent than loving, but also of repeating Joseph’s original error in a different key. Eulogies can conceal rather than reveal, bearing more the mark of their author than that of their subject. Remembering and forgetting have a strange kinship.

At the outset of Denkmal, a remembrance of his mother, the German thinker Johann Georg Hamann quotes from the poet Edward Young: “He mourns the dead, who lives as they desire.” This claim is intuitive. We often speak about the dead watching over us. We avoid giving free rein to the worst in ourselves because we fear their disappointment or disapproval, and try to live well in the hope of pleasing them or to fulfill some promise we feel we owe.

When we do this – imagining the dead as desiring in the way the living do – they can appear like someone who is just about to move, like a sleeping person on the verge of waking, as Christ and Saint Paul describe the dead. Recollecting their longings or hopes gives the dead a presence in our lives that our attempts at poetic eulogy or biography usually cannot. There was a potential in their desires when they were alive, directed at objects and conditions beyond themselves which can still seem accessible or real after they’ve died, and they, somehow, with them.

Graduation portrait of the author’s mother.

My mother wanted to be a mother, grandmother, wife, friend, and caretaker; to love and be loved in return. She wanted to be wise and sincere, to be a teacher. She had a taste for flea markets and art, and I can remember a print of Poynter’s Lesbia and Her Sparrow hanging in our home, wherein she probably saw in the figure of a gentle woman simply playing with a bird some elevated image of herself. She did not seem to want to go beyond the small circle of her friends and family, and she had hopes for all of them. I am told that she could not stand hearing about one of them being slighted or badly treated, and that she would encourage them: “Stand up for yourself!” Dignity was not something which she was willing to compromise.

She was and had many of the things she wanted. Toward the end of her life, we moved to a new home in Pennsylvania, with which she was delighted. We often traveled back to New Jersey to see our family. The last time I saw her was on one of these trips. She dropped me at a friend’s house ahead of a middle school dance, teasing me about the awkward night ahead, excitedly anticipating stories I might have to tell the next day. But by the next morning she suddenly became sick, and in a short time was gone.

We returned to Pennsylvania, and some days later it snowed for the first time on our new home, and I remember someone looking at the yard through the kitchen window, saying mournfully: “She wanted to see this.”

But when I think about all that she was not, did not have, and can no longer hope to attain, I feel an unhappy empathy for her. Her life was interrupted; her motherhood cut short. She never saw or will see in this life the fruit of her care for her children borne out in their adult lives. I can only guess as to whether she would be pleased with all the particulars of my life. But beyond this, I sometimes feel in myself not only the need to live in accordance with her wishes but to somehow fulfill what she pointed to in her life. I defend her opinions, habits, shortcomings; I articulate ideas in my own work as a teacher and researcher which I imagine she would have come to if only she had lived longer and under different circumstances. By doing this, I flatter myself into thinking I can redeem all her lost desires, ambitions, hopes; I make my own cross and, playing the type of a redeemer, imagine that I can somehow harrow hell, retrieve her, and restore her to life.

Toward the end of her life, Augustine records that his mother, Monica, said to him: “Son, for myself, I have no longer any pleasure in anything in this life. Now that my hopes in this world are satisfied, I do not know what more I want here or why I am here.” This may be the only properly Christian way to relate to desire in the face of death. And I wonder if, when recollecting the desires of the dead, and taking it onto ourselves to fulfill them, we risk robbing them of the freedom from longing that death promises. And so again I may learn and make something about myself, but I come no closer to her.

In the same breath as her final renunciation of earthly desires, Monica tells her son of a particular desire of hers which she lived to see fulfilled: “There was indeed one thing for which I wished to tarry a little in this life, and that was that I might see you a Catholic Christian before I died. My God has exceeded this abundantly, so that I see you despising all earthly felicity, made His servant.” Among her hopes in life, the longing to see Augustine share in her faith was of singular importance, in a sense the one thing needful. Seeing this desire fulfilled, she says concerning her burial: “Lay this body anywhere, let not the care for it trouble you at all. This only I ask, that you will remember me at the Lord's altar, wherever you be.”

Before God, our recollection is transfigured. Giving instructions at the Last Supper, Christ said to the disciples, and to us, “Do this in memory of me.” Worship needs remembrance, but of a special kind. What is distinct about this remembrance is that it is also a remembering forward with a view to salvation and resurrection. This includes the dead, who we recollect both as they were and as we hope they will be at the end of things.

I am blessed that my mother shared Monica’s desire: she too wished that her son would share in faith. She had me baptized and oversaw my first communion. Unlike Monica, she would never see me undergo reversion and would never share in faith with me while alive. But in this desire – that I should believe and pray for her – death is only incidental. A legitimate relationship of love can be established between her and me on the condition of the presence of a divine third.

If my earlier fears were correct and my remembrance of my mother so far has been more an act of self-making and self-knowing than one of love and recognition, it was precisely because my recollection has been purely backward, tending thereby to some secret articulation of myself. Maybe invariably the living take up too much room and the dead too little when memory rather than hope guides reflection. So if by my own power I fall into some version of Joseph’s error, I can also share in Joseph’s salvation from self-mastery and involvement. I have Christ, my own sort of Benjamin, our brother, who can with authority and not only in appearance say: “Behold your mother.”

The only explicit mention of the Joseph of Genesis in the Gospels occurs in the fourth chapter of John, in the scene of the Samaritan woman and Christ at Jacob’s well. John notes for the reader that the well is located near a plot of land that Joseph inherited from his father. Joseph’s family drama looms over the two as they discuss the woman’s own troubles at home.

The ensuing story is familiar: Christ asks the woman for a drink at the well, which she finds strange given the traditional enmity between Jews and Samaritans. Christ tells her that if she knew his identity, she would ask him for living water instead. The whole relation between the two begins to take on a new character. The woman asks Christ: “Are you greater than our father Jacob, who gave us the well and drank from it himself, as did also his sons and his livestock?”

Christ responds: “Everyone who drinks this water will be thirsty again, but whoever drinks the water I give them will never thirst. Indeed, the water I give them will become in them a spring of water welling up to eternal life.”

Jacob and Joseph defer death: Christ overcomes it. As the scholar Leon Kass notes, “Joseph’s mastery over life ends at the grave.” Once the Samaritan woman glimpses this, her own domestic struggle, a revolution of husbands, comes to light at the same time as its solution: “Woman,” Jesus says, “believe me…”

What this all points to, I think, is that the elements of the task which I set out for myself at the beginning of this remembrance can only be made coherent in light of Christ. Joseph’s wish to forget was indeed an error, which issued in a denial of his love and obscuring of his self-understanding. Only through a tearful encounter with his family could his process of reorientation toward them and himself begin. But in our case, memory, including all the elements which by themselves lead only backward, is elevated in faith and hope to a promise of future renewal and reconciliation.

At first, Augustine did not weep when Monica died. He concealed any outward sign of his pain, thinking that it would be unfitting to display distress at the death of a faithful Christian. Inside, however, he could not deny his intense grief, saying, “With a new sorrow I sorrowed for my sorrow, and was wasted by a twofold sadness.” At a loss he went to sleep, and when he awoke in his room, the words of Ambrose came to him:

O God, Creator of us all,

Guiding the orbs celestial,

Clothing the day with lovely light,

Appointing gracious sleep by night:

Thy grace our wearied limbs restore

To strengthened labor, as before,

And ease the grief of tired minds

From that deep torment which it finds

With these verses in his mind and the thought of Christ’s redemption on his heart, he began to weep. Unlike Joseph, however, he did not weep in solitude: “It was a solace to me to weep in Your sight, for her and for me, concerning her and concerning myself.” Augustine’s tears were not hidden even in private, but came forward in the presence of God: “Little by little did I bring back my former thoughts of Your handmaid.... I set free the tears which before I repressed, that they might flow at their will, spreading them beneath my heart; and it rested in them, for Your ears were near me.”

Augustine does not forget who is mother was nor who he is, but truly and lovingly remembers her and becomes clear to himself alone before God. He proceeds then to “pour out … tears of a very different sort.” These he offers in a concluding prayer for his mother and her salvation.

There is no better model of recollecting the dead than this. And so in my own remembrance I end in the way he did, praying along with him: “Forgive her debts, whatever she contracted during so many years since the water of salvation. Forgive her, O Lord, forgive her, I beseech You; enter not into judgment with her. Let Your mercy be exalted above Your justice, because Your words are true, and You have promised mercy unto the merciful.”

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.