Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Passing On the Farm to My Daughter

-

Warehouse Workers of Paris Find Their Voice

-

Building Solidarity in Europe’s Gig Economy

-

The Improbable Revival of the Cloister

-

Sailing with the Greeks

-

The Workism Trap

-

Building the Sow Shed

-

The Divine Rhythm of Work and Sabbath

-

The Work of the Poet

-

The Apurímac Clinic: A Photo Essay

-

In the Holy Land, Seeking the Solace of the Cross

-

Good Cops

-

Work that Glorifies God

-

Following the Clues of the Universe

-

Poem: “The Eye”

-

Why I Love Metalworking

-

Stanley Hauerwas’s Provocations

-

Who Will Help a Stranded Manatee?

-

The Story Behind Handel’s Messiah

-

A Delicious History of a Humble Fruit

-

Readers Respond

-

Feeding Neighbors with America’s Grow-a-Row

-

Dancing with Neighbors

-

The Rewards of Elder Care

-

Ora et Labora: The Benedictine Work Ethic

-

Rednecks and Barbarians of France

-

The Third Act of Work

-

Confessions of a Former Hack

-

A Small-Town Dentist Chooses to Stay

The Quest to Emancipate Labor

Why do we work? The dream of a truly human economy spans millennia, from Genesis to Marx to Martin Luther King.

By Peter Mommsen

March 3, 2025

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

In the summer of 1990, after I finished eighth grade, my dad decided it was time I learned to work. From as young as I can remember, I’d been tagging after him in his basement printshop, and loved helping him run the offset press. But now, he said, I was ready for more. My apprentice-master would be Ullu Keiderling, a white-bearded family friend with a blue work apron, strong Teutonic accent, and keen sense of punctuality.

The “apprenticeship” was really an informal arrangement in which I joined Ullu, a skilled craftsman, whenever I could help out on what he was doing. He showed me where he worked in the mornings: the corner of a large workshop where he built devices that aided disabled people in walking. It was an assembly job, using a standardized design and mass-produced parts, but the device was complex: bicycle wheels, casters, cotter pins, spring buttons, guide rods, and upholstered trunk and limb supports.

Several afternoons a week Ullu introduced me to his other trades. In his book bindery, he showed me how to hand-sew signatures, repair torn pages with Japanese tissue, and make a hardcover from scratch out of bookcloth, linen tape, hand-dipped endpapers, and hot bone glue. Or we’d go to his cobbler shop, redolent with the sharp tang of new leather. Apart from repairing shoes, we (mostly he) crafted custom-stamped belts, leather Bible covers, and his specialty invention, black cowhide suspenders with brass buckles that looked seriously punk.

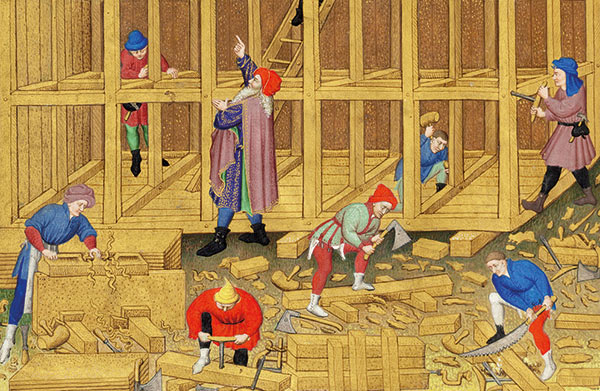

The building of Noah’s Ark, miniature from the Bedford Book of Hours, ca. 1423 (detail). All artwork from Wikimedia Images (public domain).

Ullu was a patient but exacting teacher, kind if not especially talkative. (I’d later learn that some years before he’d lost two young children, and that he lived with frequent depression.) His motions as he worked were unrushed, even when jobs were piling up. He insisted on habits of returning tools to their rightful place on the board, retrieving all dropped hardware, and regularly sweeping the floor. To him, work meant honoring a discipline, not maximizing efficiency.

Looking back, I can see that much of Ullu’s work was repetitive, even watch-the-clock boring, as I’d learn myself several years later when I got a job in that workshop. Yet certain moments from that summer stick in my memory – moments when nothing special happened but you’d suddenly catch a thrill of fascination. You’d watch him, head bowed, intent, competent, and you’d know: here’s a man who is good at his work. You’d feel a flicker of awe. This, I think, is what philosophers and theologians mean by “the dignity of work.”

This dignity is worth keeping before our eyes in a year when, many AI researchers predict, the economic value of work will begin to decline precipitously, as machines increasingly replace humans. This, according to some forecasters, will shift even more power away from workers to the owners of capital who can buy the machines. As one recent post at the Less Wrong blog wonkily puts it, “Labour-replacing AI will shift the relative importance of human v. non-human factors of production, which reduces the incentives for society to care about humans while making existing powers more effective and entrenched.” If this is true, much of our work may end up not being worth much.

Even so, Ullu’s example suggests that there’s something about work that has nothing to do with quantifiable utility. Work done well has a dignity of its own. It is a discipline that makes us more fully human.

One of the best-known celebrations of the dignity of work comes from Martin Luther King Jr.’s sermon “The Three Dimensions of a Complete Life,” which he preached many times in various versions and then published in his 1963 book Strength to Love. King argued that this dignity doesn’t depend on the earnings our labor generates or the status it gains us, but rather on striving “untiringly to achieve excellence in our lifework,” even if our job is routine or menial:

Not all men are called to specialized or professional jobs; even fewer rise to the heights of genius in the arts and sciences; many are called to be laborers in factories, fields, and streets. But no work is insignificant. All labor that uplifts humanity has dignity and importance and should be undertaken with painstaking excellence. If a man is called to be a street sweeper, he should sweep streets even as Michelangelo painted, or Beethoven composed music, or Shakespeare wrote poetry. He should sweep streets so well that all the host of heaven and earth will pause to say, “Here lived a great street sweeper who did his job well.”

Over the decades, King’s street sweeper has made countless cameos in motivational books and PowerPoints on leadership, parenting, and career advice. Just because this inspirational messaging is a cliché doesn’t make it false. It finds plenty of warrant in King’s sermon, which is filled with up-by-the-bootstraps exhortations to self-help. For example, he preaches “self-acceptance” to his often working-class hearers, and calls on them to “love themselves in a healthy way.” In his account, work offers a path to self-worth and fulfillment.

But here a nagging doubt arises: Is this actually what most people’s jobs are like? The average worker today isn’t honored for her “painstaking excellence,” but rather is managed as a replaceable “human resource” who depends for her livelihood on the whims of employers and market forces. King’s sermon may promise sanitation workers a sense of self-worth in performing low-status labor. But that doesn’t help them if they’re unable to raise a family on their wages, or if their working conditions are dangerous, or if they’re replaced by robots. Given that reality, his advice can sound like a counsel to accept exploitation. The dignity of work then becomes a useful tool for employers to secure tractable workers, whom it persuades to squander their most precious treasure – their “four thousand weeks” of life, in Oliver Burkeman’s phrase – to benefit the overclass.

This criticism may seem on-point for self-help in general. In King’s case, however, it misses the core of his message, of which self-betterment is just one part. That’s obvious to anyone with even passing familiarity with his biography as a leader in the civil rights movement and Poor People’s Campaign. His “Three Dimensions” sermon lays out the vision that guided his own work.

King launches into the sermon by marshalling the Book of Revelation as a call to build a new kind of economy, one where people are not dominated by money. (His original draft of Strength to Love appealed for “a deep-seated change” to “capitalism,” but his publisher, presumably nervous of provoking anti-Communist ire, cut the line.) King glories in Revelation’s vision of the coming of the new Jerusalem at the end of the age, contrasting the character of this heavenly city with modern America, which lives by “a practical materialism that is often more interested in things than values.” The new Jerusalem, he says, is a portrayal of the “ideal humanity” toward which he urges his hearers to strive. In this city, “the oneness of humanity and the need of an active brotherly concern for the welfare of others” will become a living reality:

God grant that we, too, will catch the vision and move with unrelenting passion toward that city of complete life in which the length and the breadth and the height are equal [Rev. 21:39]. Only by reaching this city can we achieve our true essence. Only by attaining this completeness can we be true sons of God.

This vision of a “complete life” goes well beyond advocating for worker-friendly policies. Though King doesn’t say so explicitly, its logic would ultimately transform the fundamental relationship at the core of modern work: that between employer and employee, or (as common law bluntly terms it) between “master” and “servant.” The new Jerusalem of the “ideal humanity” would seem to go beyond just striking an equitable balance between the conflicting interests of workers and bosses. Instead, in that city both parties are to become brothers and sisters, sharing not only spiritual fellowship, but practical and economic fellowship as well.

In his lifetime, King’s enemies accused him of being a Marxist, a charge he was often at pains to counter, having read Marx carefully but critically as a seminary student. Communism, he wrote in Strength to Love, is “cold atheism wrapped in the garments of materialism,” and so “provides no place for God or Christ.” But as it happens, King’s vision of the new Jerusalem is prefigured by the young Marx of the 1840s. Then a radical in his mid-twenties, Marx had not yet fully developed the “scientific” socialist theory now associated with his name, and still retained traces of the utopian Romanticism of his mentors. That idealistic impulse comes most clearly to the fore in his early writings on work.

Though the young Marx’s thinking is too complex to trace here in any detail, it’s worth highlighting certain insights on the alienation of work. Work, he writes in his Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts, is the “essence of man.” In fact, work enables us to become fully human, since it is “man’s essence in the act of proving itself.” But what happens when a worker invests her “essence” into work done for money? Her work in this case is not that of a free human being – it is not a “free activity” – but rather is reduced to a commodity to be bought and sold on the labor market. In Marx’s terms, her work is alienated.

Marx’s program, which he pursued throughout his life, was to free workers from this alienation. Despite his hostility to Christianity, this goal has theological roots, as John Hughes argues in his 2007 book The End of Work. After all, Marx can only condemn the alienation of “estranged labor” in the modern world by judging it against the standard of another possible world in which work is unalienated. In this world, everyone would work freely, since man “only truly produces in freedom” when “free from physical need.” We would work not just for survival but with an excess of creativity, as an artist works, “form[ing] things in accordance with the laws of beauty.” Work would become delight rather than drudgery.

But for Marx, this other possible world is a potential future, not anything that has ever existed in history. He is describing an age to come. Where could that idea derive from? Analyzing Marx’s early writings, Hughes argues that the source, mediated through other thinkers, is the Bible. It’s suggestive, he notes, that the way Marx describes unalienated work is the same way Christian tradition describes God’s work in creating the world.

For Marx, while the emancipation of labor was a future goal, its triumph was inevitable. The moment of liberation would arrive when capitalism collapses under its own contradictions and finally yields to communism:

In communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have in mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, shepherd, or critic.

It’s a powerfully attractive thought experiment, especially if you like hunting or fishing. And for the young Marx, the emancipation of work changes everything. It’s the key to achieving a truly humane society, one in which private property, the root of “human self-estrangement,” falls away. Then, he believed, the grim Hobbesian life of mutual antagonism would yield to fellowship and solidarity: “[Communism] is the genuine resolution of the conflict between man and nature and between man and man.… Communism is the riddle of history solved.” Here it’s hard to miss the kinship to King’s “city of complete life” in which “we achieve our true essence.”

But that, of course, is not the way Marxist communism played out in practice. When Bolshevik revolutionaries sought to solve the riddle of history by force, they rapidly proved what horrors result from attempts to impose the emancipation of labor at the barrel of a gun. The dream of freedom became a justification for mass murder and a dehumanizing system of tyranny. The twentieth century suggests that if any laws of history exist, contrary to what Marx believed they predict not the fall of capitalism but rather the totalitarian nature of political communism.

In 1919, as news of Bolshevism’s grim progress was still filtering into Germany, the founding editor of this magazine determined to build a free and cooperative life of unalienated work. Eberhard Arnold, a Berlin-based Protestant theologian and publisher, had been plunged into a crisis of conscience by the calamity of World War I, which he blamed on Christian churches’ complicity in militarism and economic injustice. Joined by a broad circle of friends that included conservative politicians, military generals, evangelicals, social reformers, and anarchists, he sought answers in “the deepest roots of Christianity.” For him, that meant rediscovering Jesus, especially his teachings in the Sermon on the Mount, which if read literally commands nonviolence, love of enemies, freedom from possessions, and unlimited sharing.

Over the course of that turbulent year, as street fighting raged in trenches outside his townhouse, Arnold came to feel an intolerable tension between his desire to practice Jesus’ teachings and his own life as an upper-middle-class intellectual. While remaining personally close to his establishment friends, he declared himself a pacifist and socialist, though defining those terms in a distinctively Christian way. He had studied Marxism and, through his involvement in political debates, came into contact with Communist cadres, negotiating with them to reduce their blacklist of enemies to execute if the planned revolution succeeded (it didn’t). But he rejected their goals and methods, insisting that “Christian communism” was voluntary and nonviolent: “We do not believe in any other weapons but those of the Spirit of love which became deed in Jesus.” The new Jerusalem would be built not by coercion but rather through a spiritual revival and the organic growth of grassroots associations. Like John Ruskin and William Morris before him, Arnold imagined a network of rural cooperatives, urban settlement houses, arts and crafts guilds, social missions, and “ancient monasteries and new Protestant orders.”

According to Revelation, not just the memory of their works, but the works themselves, accompany the righteous laborers into the new Jerusalem.

To put his new convictions into practice, in 1920 Arnold and a group of coworkers founded a small Christian community in the Hessian village of Sannerz. They planned to support themselves through farming, a children’s home, and publishing. With friends, he launched a biweekly magazine dedicated to “applications of living Christianity.” Both community and magazine bore the name Neuwerk: “new work.”

What was this new work? In a manifesto printed in the magazine, Arnold defined it in terms that sound almost Pentecostal:

We have only one weapon against the depravity that exists today – the weapon of the Spirit, which is constructive work carried out in the fellowship of love. We do not acknowledge sentimental love, love without work. Nor do we acknowledge dedication to practical work if it does not daily give proof of a heart-to-heart relationship between those who work together, a relationship that comes from the Spirit. The love of work, like the work of love, is a matter of the Spirit. The love that comes from the Spirit is work.

In contrast to the young Marx, for Arnold love comes first, as the fruit of spiritual renewal. The emancipation of labor follows as a result.

Still, for both visionaries this emancipation meant removing the domination of money over human relationships through sharing all property in common. Arnold explained Neuwerk’s goals in a letter to supporters, pointing to the early church’s practice of community of goods as described in the Book of Acts:

For us, brotherly community of goods has become something natural, an inner matter of course. We share everything, because no other relationship is any longer possible for us. What we are concerned with is a communal economy, which is not based on any kind of mutual obligations or claims. Its basis is the free spirit of the early Christians and their common life. Not only does the land belong to all; all means of production, all materials and other goods are also common property.

In such a “communal economy,” status distinctions between different kinds of work disappear, and all work attains its fullest dignity:

It is commonly argued that this is a utopia and that no one would do menial tasks unless compelled; but this reasoning is based on the false premise of present-day humanity in its moral decline. Nowadays most people lack the spirit of love that makes the lowliest practical job a source of joy. The difference between respectable and degrading work disappears when we nurse or care for someone we love. Love removes that difference and makes anything we do for the beloved person an honor.

As Arnold’s biographer Markus Baum records, Arnold applied these words to himself. Even while running the publishing house and serving as the community’s pastor, he took his turn splitting firewood and turning compost, noting the “humanizing effect” of a few hours of daily manual labor.

Over the course of the 1920s, as the Sannerz community grew to around seventy people, critics often accused it of withdrawing from society in a quest for religious purity. Arnold responded that the point was not to gather a spiritual elite. He disavowed any pretension that groups like his could fully extract themselves from the “worldwide capitalist economy,” and rejected any claim to moral heroism: “None of us believe we are capable of creating anything better or more religious than other Christians.”

Instead, his goal was to build a practical life of Christian discipleship that was open to anyone, from homeless war veterans to single mothers to disillusioned youth. Theirs would be a small and inevitably imperfect experiment, yet still a living proof that another life is possible. “Faith demands … that we risk and dare everything out of love in order to find new, practical ways leading to brotherliness, to a society free of discrimination, to sharing all work and goods so that personal property, and capitalism’s stratification of human beings through money, are overcome.” This communal life – one in which “work is love, and love is work” – would be a microcosm of the new Jerusalem.

The successors to Eberhard Arnold’s community and magazine still exist, having escaped National Socialist Germany in 1937 and then moved from England to South America to the United States. The magazine is the one you’re holding, and the community is now known as the Bruderhof, Plough’s publisher. Ullu, who still remembered Arnold from living in the German Bruderhof as a child, had lived through much of this history by the time he taught me to bind books and make belts in eighth grade in a Bruderhof in upstate New York.

In retrospect, Ullu’s work that summer bore an uncanny similarity to the young Marx’s evocation of what unalienated labor would be like. His days alternated freely between the workshop, book binding, and shoe repair, just as Marx had fantasized about a varied schedule of hunting, fishing, and literary criticism. I realize now that this freedom resulted from the “communal economy” that Arnold and his Sannerz friends had called into being. Ullu’s work wasn’t a job to him. As a Bruderhof member, he received no pay, and though he was of course accountable to the community, he had no boss. When he and his fellow old-timers were occasionally asked by visitors if they ever got a vacation, they would reply, “Vacation from what?” Their work was their love, and their love was their work. “To work is to pray,” runs an old Benedictine motto – laborare est orare – and while that may not apply to every job, for Ullu’s work it held true.

Over several weeks that June, Ullu built a circular stone wall at the entrance to the community’s campus, surrounding a linden tree. It was a sweaty Hudson Valley summer, the circle was to be twenty-five feet in diameter, and it was my job to haul the undressed stones for Ullu to fit in. When the wall was almost complete, he beckoned me over, pointing to a hidden niche he’d built into the structure. That was for the time capsule, he said. We collected a boxful of artifacts of that year – including, as I remember, several new Plough books – sealed them in an airtight container, and cemented it into the secret chamber for a future archaeologist, with “1920–1990” chiseled into the rock.

Ullu Keiderling with a grandchild in 1995. Photograph courtesy of the Keiderling family.

Ullu continued to work until a few days before he died in 2014, and his stone wall still stands, the capsule still waiting. They won’t last forever, of course. Neither will the community or magazine that Arnold founded (though I hope they both still have a long run ahead of them). All human work, the “new work” included, dies in the end, according to the Book of Ecclesiastes. “What does man gain by all the toil at which he toils under the sun?” it asks bleakly. “All [is] vanity and a striving after wind.”

Or is it? King’s parable of the street sweeper points at another possibility. It seems that in the story the street sweeper dies. Will the hard-won dignity of his work now vanish into oblivion, as Ecclesiastes would have it? Not according to the story’s ending, since his labor receives heavenly approbation: “The host of heaven and earth will pause to say, ‘Here lived a great street sweeper who did his job well.’” Somehow, it seems, the mark of the man’s work endures.

The Book of Revelation makes the point even more plainly a few chapters before the verse King used for his sermon. In this passage, John of Patmos hears a heavenly voice instructing him, “Write: Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord from henceforth: Yea, saith the Spirit, that they may rest from their labours; and their works do follow them” (Rev. 14:13). According to this prophecy, not just the memory of their works, but the works themselves, accompany the righteous laborers into the new Jerusalem.

Perhaps this verse echoed in King’s mind in telling his parable – from his work as a pastor, he would have known it as a staple at Christian funeral services. In any case, the biblical promise that “their works do follow them” seems to apply to those who, like King, dare everything to build the “city of complete life.” And for the rest of us, Revelation assures us that the same promise will apply to anyone – hunter, fisherman, critic, whatever the trade – who sets his or her hand to the new work, and performs it with painstaking excellence.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Linda and John wilson

This Alisdair Macintyre’s thoughts on Marxism I referred to in my previous comment: “I should also make it clear that, although “After Virtue” was written in part out of a recognition of those moral inadequacies of Marxism which its twentieth-century history had disclosed, I was and remain deeply indebted to Marx’s critique of the economic, social, and cultural order of capitalism and to the development of that critique by later Marxists. “In the last sentence of “After Virtue” I spoke of us as waiting for another St. Benedict. Benedict’s greatness lay in making possible a quite new kind of institution, that of the monastery of prayer, learning, and labor, in which and around which communities could not only survive, but flourish in a period of social and cultural darkness. The effects of Benedict’s founding insights and of their institutional embodiment by those who learned from them were from the standpoint of his own age quite unpredictable. And it was my intention to suggest, when I wrote that last sentence in 1980, that ours too is a time of waiting for new and unpredictable possibilities of renewal. It is also a time for resisting as prudently and courageously and justly and temperately as possible the dominant social, economic, and political order of advanced modernity. So it was twenty-six years ago, so it is still.” Alisdair Macintyre, “After Virtue” Cordially, J. D. Wilson, Jr.

Linda and John wilson

When I was younger, I worked on a Kibbutz in Israel. I worked in fishponds, picked fruit (apples, peaches, and pears mostly), I worked in the chicken house, did dishes, and other odds and ends. But it was all mostly agricultural in nature. While in Israel I also worked on a copper mine. I shoveled sulfur, dug ditches, swept floors, toted stuff from one place to another. When I started teaching, I did temp jobs in the summer that ranged from office work to sweeping floors. In work study jobs in college I ran a cash register, stocked shelves, packaged items for return to publishers and manufacturers. My point is that I was always working around people that did those things full time. I learned from this work that not only is it dignified, not only does it demand certain skills (I know for a fact a professional laborer can dig ditches better, faster, and more effectively than I ever could. People mock many of these jobs because they are “unskilled labor,” but I know that most “unskilled labor” demands certain skills to be done well, we just do not value those skills. John Ruskin in his book The Nature of the Gothic (William Morris produced a beautiful edition of this book on his Kelmscott Press) wrote about work and the worker, “You must either make a tool of the creature, or a man of him. You cannot make both. Men were not intended to work with the accuracy of tools, to be precise and perfect in all their actions. If you will have that precision out of them, and make their fingers measure degrees like cogwheels, and their arms strike curves like compasses, you must unhumanize them. All the energy of their spirits must be given to make cogs and compasses of themselves. All their attention and strength must go to the accomplishment of the mean act.” Ruskin was talking about the stone cutters that made Gothic cathedrals, but there is a truth here that applies to all work. I do not know what jobs AI will replace, but the same was said about robotics, but robotics has not entirely replaced human workers and in many cases the menial jobs done by robots were replaced by less menial jobs for human beings. Perhaps something similar will happen with AI. I do not think machines can bring to a task what a human can and machines do not generally do work that requires judgement or imagination, and I do not think AI posses judgment or imagination. Time will tell. I think it also important to remember what scripture says about labor and management. “Look! The wages you failed to pay the workers who mowed your fields are crying out against you. The cries of the harvesters have reached the ears of the Lord Almighty.” James 5:4 and “Pay them their wages each day before sunset, because they are poor and are counting on it. Otherwise they may cry to the Lord against you, and you will be guilty of sin.” Deuteronomy 24:15. I think Martin Luther King, Jr.’s description of the nature of work says most all that needs to be said about work and how the worker ought to be treated and understood. Cordially, J. D. Wilson, Jr.