Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Telling a Tale of Two Fathers (Video)

-

Home Is Not Just a Place

-

The Quest for Home

-

In Search of Lost Fig Trees

-

Child of the Stars

-

Refugee Letters

-

Life in Zion

-

How to Run a Cemetery

-

Integrity and the Future of the Church

-

Daring to Follow the Call

-

Poem: “For the Celts”

-

Poem: “Wreathmaking”

-

Poem: “The Hunger Winter, 1944–5”

-

Editors’ Picks: The Cult of Smart

-

Editors’ Picks: The Utopians

-

Editors’ Picks: The Lincoln Highway

-

Casa de Paz

-

The Pilsdon Community

-

Letters from Readers

-

Nonexistence Does Not Scare Me

-

Toyohiko Kagawa

-

Covering the Cover: Beyond Borders

-

Choosing America

-

Church as Sanctuary and Shelter

-

Northern Ireland’s New Troubles

-

When Migrants Come Knocking

-

The Florentine Option

-

Three Kants and a Thousand Skulls

The End of Rage

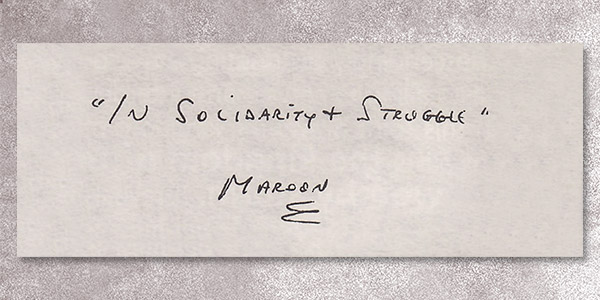

A Black Panther in prison makes a reckoning: the story of Russell Maroon Shoatz.

By Ashley Lucas

September 14, 2021

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

For the sources and backstory for this article, see the Note on Sources.

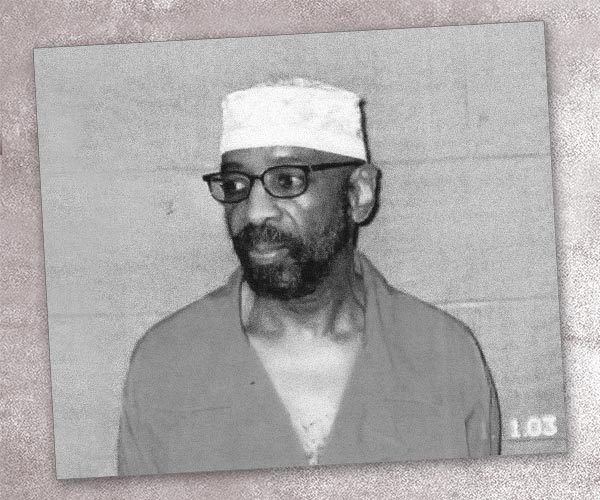

I. FATHER, PANTHER, SOLDIER, SPY

In 2014 in Pennsylvania, Russell Maroon Shoatz was released from twenty-two consecutive years of solitary confinement into the general prison population. This is twenty-one years and fifty weeks longer than the length of time in solitary the United Nations has deemed to be torture. Having spent so much time in a small space, he had trouble walking and could not climb the stairs to the cafeteria. He felt overwhelmed by other people, whose presence he had so desperately missed for all those years. Known to his supporters inside and outside the prison as a Black liberation leader, he now found it physically difficult to stand up tall. That he was even alive was more than many who considered him a cop killer wanted: they believed that his punishment should have been death.

Later that same year, in Ferguson, Missouri, Michael Brown was fatally shot by police officer Darren Wilson. Brown’s body was left in the street for several hours and no charges were ever filed against the officer. In response, Black Lives Matter bloomed into a protest movement. Despite all that had changed since Russell went to prison in 1972, this was a direct echo of the past. Nearly fifty years before, in Philadelphia, he had witnessed a similar killing of a young Black man by a police officer, even down to the body neglected by authorities on the scene and the lack of repercussions. This and other such events catalyzed Russell and his activist friends to become militant revolutionaries.

Russell Maroon Shoatz

Not long before, in 1966, another Black leader had warned that people were losing faith in the democratic process and nonviolent change. “Those who make this peaceful revolution impossible will make a violent revolution inevitable,” said Martin Luther King Jr., standard-bearer for the peaceful revolution, with a message directed at those in power. Of course, the powerful did not want even a nonviolent revolution, and instead cracked down on dissidents of all stripes.

In Philadelphia, where Russell lived, Frank Rizzo became police commissioner in 1967 and was later elected mayor. As the number of Black people shot or killed by police spiked under his leadership, Rizzo made it known that no allegations of police misconduct would be investigated under his watch. The killings and lack of accountability inspired an abundance of activism that ranged from the formation of civic organizations focused on registering the city’s Black voters to a variety of militant Black nationalist groups. In turn, Rizzo formed a Civil Defense Squad to aggressively gather information on left-wing activists (including students), alternative-newspaper publishers, and Black revolutionaries. The FBI modeled its COINTELPRO surveillance program on Rizzo’s Civil Defense Squad and used it to launch a national campaign to harass and disrupt leftist radicals, including the Black Panther Party.

Frank Rizzo, Philadelphia's police commissioner (1968–71) and mayor (1972–80) File photograph from the Philadelphia Inquirer, 1969

Russell was among these radicals, living underground as a member of Philadelphia’s Black Liberation Army, a highly secretive revolutionary group connected to but distinct from the Black Panthers. In 1972, he was arrested and convicted of the politically motivated August 29, 1970, shooting of two White police officers, Sergeant Frank Von Colln (who died) and Patrolman James Harrington (who lived). Russell later escaped from prison twice.

To some in the Philadelphia radical community of the early 1970s, Russell was a freedom fighter, taking up arms against the true sources of terror in the United States: the authorities who dealt violence to Blacks and other minorities. To these authorities, he was a dangerous political extremist. To his family, he was an absence – the father who wasn’t there. To the families of two police officers, he was the source of terrible grief.

Russell became many other versions of himself in the decades that followed. His conception of his own identity, beliefs, and political philosophies transformed and contradicted themselves over and over again. His story, emblematic as it is of an era when young people went to one extreme after another to transform an unjust world, has never been told at this length before. It tells us much about racism, violence, suffering, public safety, law enforcement, and social transformation. The most important thing it tells us is that no true story, however detailed, can make all these forms of suffering balance out against each other, as in a ledger. An honest account can only push us up against their complexities, again and again.

The year Russell went to prison, his son and namesake Russell III went to kindergarten. In a profound sense, they were each on their own at the beginning of something momentous – one having just received a life sentence and the other starting school without a father, neither one of them with any way to reach out to the other. Russell III would not comprehend the events that led to his father’s incarceration or the context surrounding them for many years, and had no idea that it would become his life’s work to advocate for his father’s release. Something else happened at the same time that would also change the course of Russell III’s life – his informal adoption by a police officer, who could easily have been the one shot that night.

Born in 1941 in North Carolina, Claude Barnes knew the terrors of the segregated South and felt keenly his powerlessness to combat them. From childhood, he dreamed of becoming a police officer – someone who could hold authority and help end the violence that threatened everyday people. He says that in his youth his motives were not always pure. He was envious of those with power and wanted some of his own. By the time he reached his mid-twenties, Barnes had become a devout Christian and believed that he could serve God and his people by joining the Philadelphia police force, which he did in November 1966. He married and started a family. His son Reggie wound up in the same kindergarten class as a boy who seemed to need a friend.

Claude "Papa" Barnes, a Philadelphia police officer (retired) and bishop of the Church of Faith on North 38th Street Image from the Philadelphia Tribune

Claude Barnes loved being a father and was eager to embrace and mentor all the boys in the neighborhood, especially those who befriended Reggie. When Barnes met Russell III, he unknowingly stood at a crucial intersection of two powerful forces in the child’s life: fathering and policing. Barnes was on the Philadelphia police force in August 1970 when six officers were shot in three different incidents on the same weekend. The historical record suggests that none of the individual policemen had been specifically targeted. The assailants had been willing to shoot any officer they encountered, rather than seeking out particular policemen who had records of racist or brutal behavior. If Barnes had been on duty on August 29, he could have been one of the men Russell Shoatz and others were later convicted of shooting. Barnes had, of course, heard about these cases, but he did not immediately make the connection to the kindergartener who spent many afternoons at his home. In time, the boy would say things about his father that made Barnes understand who he was. “Quite naturally, that gave me mixed emotions because I loved Russell, and I also knew that his father was a very important part of his life,” Barnes says. Russell III knew that the man he came to call Papa Barnes worked as a police officer, but the significance of that fact did not register for him just yet.

As a Black officer who worked for years under Frank Rizzo, Barnes knew all too well the tensions between trying to keep communities safe and the racist and deadly potential of policing. Barnes did his best to keep people safe and to be a role model for the youth in his community. He managed this remarkably well, never once pointing his service revolver at anyone in the twenty years he was on the force. For ten of those years, Barnes worked as part of a community-relations police unit, “trying to educate the people on how they could resolve problems in their own neighborhood without calling the police.”

Growing up six blocks away from where his father had lived as a child, Russell III describes the “frightening times” brought on his neighborhood by Rizzo’s police force. He routinely watched Black men “just getting it” from the cops. An institution meant to keep the peace, protect the people, and “stop injustice from happening” has not played anything like this role in his life or that of his peers. It takes “constant ducking and dodging just to be a human” and a police officer at the same time, Russell III says. He calls this the “cop dance” and admires Papa Barnes for having the strength to do it for decades.

Russell III and Papa Barnes became so attached to one another that they consider themselves family and requested that I interview them together for this story. Barnes’s own father was distant, and he says he recognized himself in Russell III and understood how it felt to have a father who existed but was not there when you needed him. When I asked Barnes if his colleagues on the force knew that he had a close relationship with the son of a man convicted of killing a fellow officer, he said he had never thought to tell anyone at work: Russell III is like his own son, and that’s no one else’s business. At this point in our conversation, Russell III thanked Papa Barnes and said he had not previously been brave enough to state publicly that “my non-biological father is a police officer.” Barnes replied, “You have nothing to be ashamed of.”

His love for Russell III and his understanding that sometimes “the system works against African Americans” make Barnes wish that he could speak to the elder Russell. Barnes would like to ask Russell what he was thinking on the night of the crime that sent him to prison and give him a police officer’s perspective on it. Barnes also would like to tell Russell more about his son, what he has been doing all these years, and what a good man Russell III grew up to be. Most of all, Barnes wants Russell to know that he can still make the best of however much time he has left on this earth. Barnes says, “It’s not how you start off. It’s how you finish.” He wants Russell to offer up a sincere, public apology to those he has harmed and to find peace before the end of his life. Barnes is praying for God to touch Russell’s heart, for God to lead Russell toward reconciliation and redemption.

Until now, Russell has never offered such an apology.

The Making of a Revolutionary

Russell Shoatz still remembers the first time he saw racist violence. As a small child in the 1940s, he watched as two White police officers responded to a call about domestic violence in a working-class Black area of Philadelphia. The neighbors watched from their porches and windows as the policemen dragged a man from his house, beating him and hurling racial epithets as they shoved him into the car. One of the policemen turned to the onlookers and asked, “Any of you other n----rs want any of this?”

From his preteen years onward, Russell had ugly interactions with law enforcement. By the time he was thirteen, he and his friends had come to accept police brutality as a routine part of their lives. They were regularly roughed up by patrolmen and told to expect this by the “old heads” – the more grown-up gang members in their neighborhood. Russell describes a culture of frequent brawls between opposing gangs, and old heads coercing adolescent boys to become drug runners. Also, the old heads’ dismissive and sometimes brutal treatment of women influenced his own behavior toward women in his life.

Russell spent several stints in juvenile detention facilities, including a wilderness camp for wayward youth where he learned survival skills that he would later employ after an escape from adult prison. By his teenage years in the late 1950s he was a self-described “street thug.”

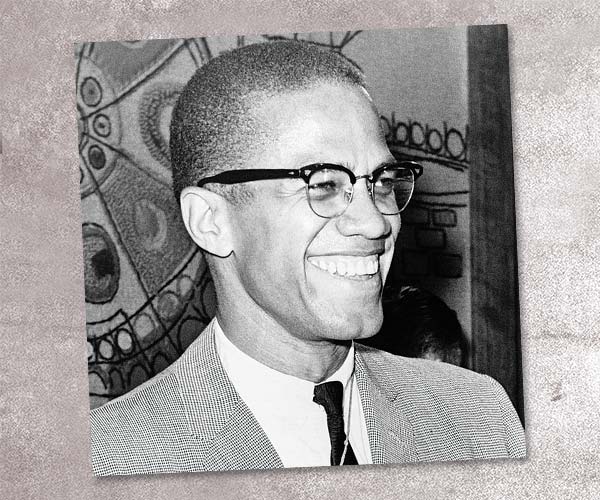

Malcolm X, 1964: “We are nonviolent with people who are nonviolent with us.” Photograph from Wikipedia (public domain)

The moment that changed Russell’s life took place on a New York street corner in 1963, where he saw Malcolm X address a rally. “Within the first five minutes of hearing Malcolm speak, I knew this was not a man like any that I knew or ever heard about.” Malcolm’s descriptions of “police brutality, the brutality that the community members visited on each other, [and] the absurdity of demanding that civil rights demonstrators not defend themselves from attack” gave Russell a new framework for understanding his own life. Russell saw in Malcolm a figure of strength with a more noble purpose than the old heads on the corner. He committed himself to turning his life in this direction but did not know where to begin.

It wasn’t until after Malcolm X’s assassination a few years later that Russell found his way to the Muntu Cultural Center, a community space run by a Philadelphia organization called the Black Coalition. There, he learned to take pride in his African heritage instead of feeling shame; he immersed himself in art, music, food, stories, and traditions. He was inspired by the group’s leaders, who called on the Black community to come together and stand up for itself.

Building on their encounters with local activists, Russell, his sister Gloria, and several others decided to form their own group called the Black Unity Council. The BUC’s original intent was to start another community center with a food bank, daycare, gang intervention programs, and a “liberation school” to educate Black children about their history. The BUC successfully organized a Black caucus within a local union to protect the interests of workers ignored by the White leadership, and won significant gains for its members.

Interacting with the BUC was also the first step toward changing Russell’s view of women. As part of the community’s accountability, the men “could be hauled before the group and judged because of any of their former practices that brutalized women. In turn, this gave the women more freedom to speak their minds.” He came to see “that women could and would exhibit courage in situations that made most men withdraw in fear.” Meanwhile, he worked on deconstructing other behaviors from his old gang life, trying to defuse what he now saw as pointless scrapping among the young boys of the neighborhood. In talking them out of a planned violent retaliation against another gang, “I was not able to offer them anything in return for not doing this except to constantly repeat the idea that we should not be killing each other over much of nothing.”

Russell had always been skeptical of nonviolent resistance in the civil rights movement. “I had been taught that one did not allow another to attack them, under any circumstances!” Though he developed a grudging respect for the courage peaceful demonstrators showed under duress, when he became politically engaged he was convinced that their actions could not deliver Black people from oppression.

By the time he was thirteen, Russell and his friends had come to accept police brutality as a routine part of their lives.

Sometime in the late 1960s, Russell witnessed a particularly harrowing police killing of a young Black man in his neighborhood. Officers on Rizzo’s force engaged in a car chase with a man suspected of joyriding. When the young man abandoned the car and ran away on foot, an officer pursued him to his home and shot him as he tried to hide behind his mother. The son managed to run into the yard, where the officer shot him several more times. The mother grabbed a kitchen knife and stabbed the cop to try to defend her son. As her son’s body lay on the ground, a crowd of neighbors, including Russell, were drawn to the yard. The paramedics who arrived left the son’s body lying and set about treating the officer. The mother stood over her son in a pool of blood and told everyone gathered what had happened. Before this moment, Russell had always accepted whatever violence the police had meted out to him and his friends. As he listened to this mother, something in him shifted: “I almost lost control of myself and had to fight down an urge to jump one of the policemen that was mingling in the crowd … to take his weapon and shoot him with it.” He refrained from retaliating that day but resolved to take a new kind of action: community organizing to prevent further police murders.

To address this killing, various groups, including the BUC, convened a series of forums, some of which included police representatives. It quickly became clear to the activists that the authorities had no intention of offering a meaningful response. In a meeting with the slain boy’s mother, Russell learned that her report of the event had been administratively buried, as if none of it had ever happened.

After the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, Russell and several others set fire to several White-owned businesses in their neighborhood that they believed were exploiting the Black residents. Becoming increasingly radicalized and considering nonviolent strategies to be dead ends, they decided that the BUC needed a paramilitary wing. Russell and his comrades “believed that militia-style organizations that were set up, organized, trained, and controlled by the Black community” could protect Black efforts at political organizing and community projects. In a 2006 interview, he said, “Rightly or wrongly, the BUC had reached the conclusion that in order for Blacks in the United States to be truly free, we would have to wage armed struggle.”

This was a period of US history in which all over the country young people of various racial, ethnic, and social backgrounds were going underground – forming secretive radical groups which bombed corporate and government targets, helped their comrades escape from prisons, and killed police officers. Some of this political violence happened in protest of US military operations in Vietnam, but often it took the form of retaliatory responses to police or FBI killings of Black people. These groups thought a revolution was coming and soon. In his 2015 book Days of Rage, Bryan Burrough characterizes the story of the underground as “ultimately a tragic tale, defined by one unavoidable irony: that so many idealistic young Americans, passionately committed to creating a better world for themselves and those less fortunate, believed they had to kill people to do it.”

Russell would become one of these young people, helping to form the Philadelphia cell of an amorphous group – one so secretive and little-documented that researchers of the period cannot even be sure that the various groups using this name knew about each other – called the Black Liberation Army.

Offense as Defense

While the Black Panthers, formed in 1966 in Oakland, California, were gaining notoriety and seeding new chapters across the country, the BUC stayed small and local with a decidedly militant mindset. By the summer of 1969, the BUC had acquired a significant amount of weaponry, even including a box of US military hand grenades, and had to keep a low profile to avoid discovery. This put a damper on the charter members’ plans to establish a daycare and community center, and caused the departure of the majority of the BUC’s members. After the split, only about eight men and their female partners remained in the group, including Russell and the woman who would become his common-law wife. The group decided to rename themselves the Black Liberation Army (BLA) – a moniker they adopted because they had heard of such a group in Washington, DC. At the time they had no knowledge of or connection to what would later come to be the more famous New York–based organization using that name, which included Assata Shakur and Sekou Odinga.

After the December 1969 murder of Fred Hampton (subject of the 2021 biopic Judas and the Black Messiah), who was drugged by an FBI informant and shot by Chicago police as he slept next to his pregnant girlfriend, Russell and his BLA comrades decided to stay close to the Panther chapter in Philadelphia to “upgrade their defenses and react to the expected attacks” from police.

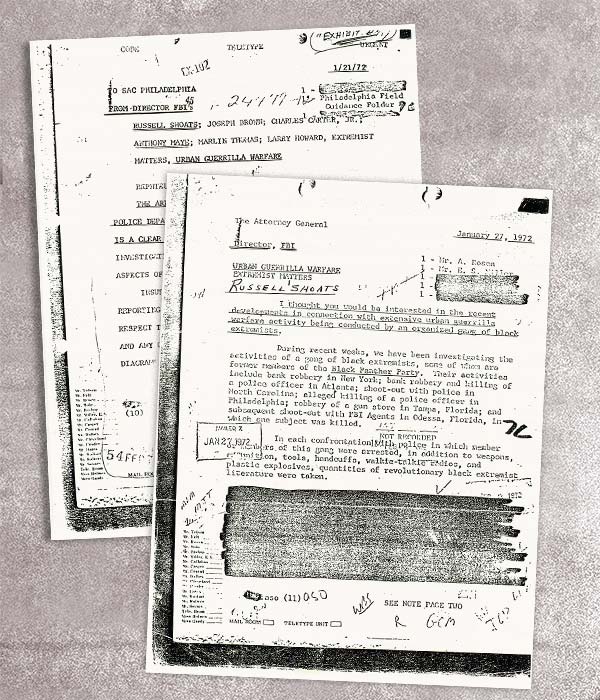

COINTELPRO files on Russell Shoatz show the direct involvement of J. Edgar Hoover, director of the FBI, and John N. Mitchell, the US attorney general, who would himself be imprisoned as a conspirator in the Watergate scandal. FBI files obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request by Russell Shoatz.

Meanwhile, the national Panther organization had the same kinds of ideological differences that led to the dissolution of the BUC, egged on by interference from COINTELPRO. The assassination of a young Panther field marshal named Robert Webb, which was blamed on a rival Panther faction but evidence suggests may have been done by COINTELPRO, was the catalyst for the creation of the New York cells of the Black Liberation Army. What is known about the activities of any of these factions can only be told in fragments. The secrecy, anger, and fear that shrouded the actions of the BLA, the Panthers, the FBI, and the police prevent even those involved in these organizations from fully knowing what occurred. In a 2006 interview, Russell described this as a necessary strategy to enable revolutionary actions:

People must understand that in dealing with the history of the Black Panther Party, nobody – not the Panthers, not the police/FBI or other repressive arms of the state – knows it all! … A lot of stuff was so delicate that it was known and handled only by those who needed to know about it, the downside to this being that if things didn’t go right, or if you got caught, you were on your own.

Unlike groups such as the Weather Underground, the BLA did not release substantial political manifestos describing its philosophies or its vision for the revolution. It was not a formal part of the Black Panther Party, though the vast majority of the BLA’s members had been Panthers at some point. What seemed to unite all the members of the various BLA cells was their sense that the necessary response to the ongoing police murders of young Black people was to respond in kind by killing policemen.

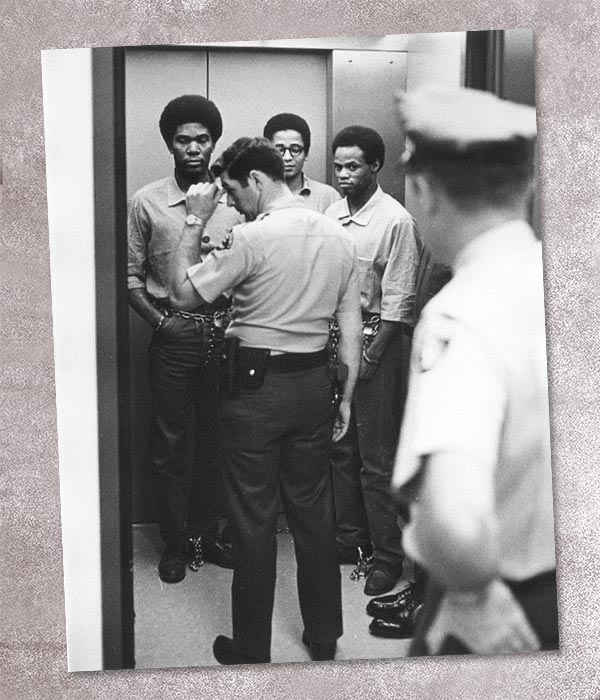

Gunshots

August 7, 1970: Seventeen-year-old Black Panther Jonathan Jackson and five accomplices used shotguns to take over a courtroom in the Marin County Courthouse in northern California and demand the release of a group of Panthers known as the Soledad Brothers, including Jonathan’s brother George. Five hostages, including the judge, prosecutor, and three jurors, left the courthouse at gunpoint. The ensuing gun battle with police left Jonathan, two other Panthers, and the judge dead. The prosecutor and another Panther suffered serious wounds. Jonathan Jackson became a martyr to the Panthers and an inspiration to Russell Shoatz. “This is what so many of us had been waiting and training for,” he recounts in his unpublished 2001 autobiography. “My feeling was, in street language: the shit was on!”

John Clutchette, George Jackson, and Fleeta Drumgo (the "Soledad Brothers"), 1970 Image from SF Bay View

August 29, 1970: Thirty-nine-year-old Patrolman James Harrington was driving with his partner, Henry Kenner, in a police van about one hundred yards away from the guard house at Fairmount Park in Philadelphia when an unknown man waved them down – Harrington assumed to ask for directions – and then, without a word, shot him point blank. The bullet entered his chin and came out the back of his neck. Harrington lived. Kenner, a Black officer, was unharmed. Blood and bone fragments filled what was left of Harrington’s mouth as he tried to radio for help. His injuries cost him his teeth and lower jaw, as well as full hearing loss in one ear and partial in the other.

Half an hour later, forty-three-year-old Sergeant Frank Von Colln sat talking on the phone at his desk at the guard house. An unidentified man fatally shot Von Colln five times. No clear evidence was ever found to identify the shooter in either case. However, in his autobiography Russell admits to being “at the immediate scene of those events” and asserts that these acts were “carried out in accord with and at the behest of the leadership of the Black Panther Party.”

August 30, 1970: In two separate incidents, four more Philadelphia police officers were shot. Russell references one of these shootings as being carried out by comrades in another underground cell affiliated with his. Another source claims that these later shootings proved not to be linked to the prior day’s violence or the Panthers, but police commissioner Frank Rizzo – a man not in the habit of making careful distinctions among Black people – and many others assumed that the Panthers were behind all of these attacks on police. Rizzo ordered 5 a.m. raids of Black Panther offices in three different Philadelphia neighborhoods.

Three suspects (Hugh Williams and brothers Robert and Alvin Joyner) were arrested within days, and a fourth (Fred Burton) surrendered a month later, but Russell Shoatz was not found in any of these raids. He had already gone underground, and would not be caught until January 19, 1972, when he was arrested under a false name on a weapons charge. His fingerprints revealed his identity and alerted the police that he was wanted for the Fairmount Park shootings.

These five men were ultimately convicted of the Harrington shooting and Von Colln murder. (A sixth suspect, Richard Bernard Thomas, was captured in 1996, twenty-six years after the attack, living under a new identity. He was acquitted, as witness testimony had deteriorated in the intervening years.) The victims’ families wanted the defendants to receive the death penalty. Four of the men known during their trials as the Philadelphia Five are serving life without parole sentences in Pennsylvania prisons for first-degree murder. (Life sentences in Pennsylvania exclude the possibility of parole.) Russell, who was portrayed as the ringleader and later received extra sentences for two successful prison breaks, is serving two life sentences plus twenty-five years. All of the Philadelphia Five were offered sentence reductions if they would give evidence against the others, but none did so. They made a pact to one another that half a century of incarceration has not eroded.

II. THE REVOLUTIONARY’S FAMILY

For most of the three years before the FBI came to her house looking for him, Thelma Christian had no idea where her husband had gone. Moreover, she didn’t care.

To those FBI agents, on that day in late 1970 or early 1971, Russell was a terrorist. To Thelma, he was merely a difficult and absent husband. It was no simple matter for a twenty-six-year-old Black woman in Philadelphia to support herself and her four young children, but Thelma was relieved not to have to deal with the abuse that had ended when her husband left.

Thelma hadn’t seen Russell in months when he appeared on her doorstep earlier on the same day she received a visit from the FBI. He was sweaty and looked like he had been running. Thelma let him into the house but only for a moment. Russell wanted to see his children, but Thelma told him they were staying with her family in Virginia for the summer. She thought there was something strange going on but didn’t want to question him. He left within minutes, and she was glad to see him go.

Then without warning the FBI arrived with guns and pushed their way into her house. Thelma was terrified. They came in asking for Russell, and she told them he had just left. When the door closed behind them, she almost passed out. This incident was the first indication she had that her husband was wanted by the police or that he might have committed a serious crime.

Behind every successful or failed revolution, there are the untold stories of people who keep life going day to day, picking up the pieces and caring for the children.

For years to come, Thelma would assume her phone was tapped. She thought she could hear the sound of a machine recording her, so she seldom made calls. She would be questioned on multiple occasions and given a lie detector test, which she failed because she was so nervous. Though every authority with whom she came into contact ultimately concluded that Thelma knew nothing of Russell’s revolutionary activities, her home would be raided multiple times – the doors kicked in, SWAT teams pulling things off the walls, helicopters circling overhead, men with guns surrounding her house and endangering her and her children.

Thelma had separated from her husband three years prior to the crimes for which he would be convicted. Despite this, for the last fifty years, her life and the lives of her children have been profoundly shaped by violence and surveillance at the hands of law enforcement agents, the courts that gave them warrants, and the public’s judgment of actions of which she had no knowledge and in which she did not participate.

Behind every successful or failed revolution, there are the untold stories of people who keep life going day to day, picking up the pieces and caring for the children. In the Shoatz family, this fell to Thelma.

When Thelma Married Russell

Thelma says she never liked the man who would become her husband. She had moved to Philadelphia from Virginia with two of her older sisters and was starting a new life in the big city. From the moment Russell met her he pursued her aggressively, although she refused him many times. It was the early 1960s, and many men still lived a script that portrayed such persistence as romantic. Thelma eventually relented and went out with him. They found out a few weeks later that she was pregnant.

Russell’s family insisted on a wedding and paid for everything. No one asked Thelma what she wanted or how she felt about it. When she and Russell married in March of 1964, she cried throughout the ceremony. Later that year she gave birth to their daughter Theresa. When the two new parents went to the doctor for her postpartum checkup, they discovered that another baby (their daughter Sharon) was already on the way. They would have four children in as many years.

Thelma had her own political interests; she was involved in the civil rights movement, including the march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, where John Lewis was clubbed by state troopers and she sustained injuries herself. Still, she remained committed to the cause of nonviolent demonstration. With so many young children, she was mostly tied to the home front anyway. Her life was no longer her own.

Thelma and Russell’s marriage deteriorated quickly, accelerated by his philandering and aggression. He was struggling to reconcile the life he had known with Malcolm X’s vision of the revolution, wanting change but not knowing how. During this period, Russell met a woman nicknamed Bonnie (legal name Loretta Fairly), who was also married with children but separated from her husband. The two bonded over their similarly chaotic lives as they became both lovers and friends. Though Russell wanted to stay married to Thelma, he turned to Bonnie for emotional intimacy and comfort.

He got into fights with men in the neighborhood and hit Thelma when they argued. On one such occasion, she ran out of the house and called the police. Russell shut the door when the police asked to come into his home, and though they could see clearly through the front window that he was unarmed and wearing only his underwear, they broke down the door, beat him into submission, and hauled him to the station.

When Russell’s father bailed him out of jail the next day, he told his son he should have used his shotgun on the officers when they broke down his door. This was uncharacteristic for Russell Sr., who until then had tried to teach his son to keep his head down and play by the rules. Russell describes his parents as “under the illusion that if they just helped me become a healthy, educated member of the broader society, from that start I had an excellent chance of becoming a stable and productive member of the community. Many years later I would hear them both say that their visions were doomed because of forces they never imagined would come into play, though being from the segregated and repressive Southern states, they were aware of them. They just thought they had escaped them.”

In 1967 Russell was present at the hospital for Thelma’s delivery of their son Russell III. Less than a year later, Thelma gave birth to their last baby, a girl named Tammy, but by this point, the couple had split. Russell became more committed to Bonnie, and around the time Tammy was born, Bonnie became pregnant with the first of the three children she would have with Russell – Hassan, Naeemah, and Jalilah. This period coincided with Russell’s awakening to Black liberation, a cause in which Bonnie was also engaged.

Meanwhile, Thelma took her four young children back to Virginia. After struggling to care for them, Thelma agreed to let the two oldest, Theresa and Sharon, return to Philadelphia to live with their father and Bonnie for a while. In the two years that Russell and Bonnie were raising Thelma’s girls, they had a large blackboard, a desk, and chairs set up in the living room. They wanted the children to have a “revolutionary education.” Russell “had hopes of preparing them to carry on our Liberation Struggle, as I felt sure I would either be killed or jailed.”

After two years, Thelma returned to reclaim her daughters, and she was appalled at the state in which she found them. Thelma would never leave any of her children in Russell’s care again, despite her profound struggles to support them on her own. Neither Russell’s family nor her own helped Thelma stay afloat financially or took them in when they needed a place to live. Theresa remembers walking with her mother and siblings in the cold looking for a place to stay. The Great Migration was still bringing southerners north to Philadelphia to look for work, and both housing and employment were hard to come by, but Thelma found a room to rent and did her best to make ends meet.

She was glad to be together again with her children, but often found it nearly impossible to go on. She would cry out, “Where are you, God, where are you? Do you see all of this stuff I’m going through? Where are you?” When she was on the edge of despair, she would look at her babies and remember that they had no one but her, and she would resolve again to trust in God. “He is my provider, my protector, and I can go to him for anything that I need.”

The Fog of War

During this period, Russell, Bonnie, and their children were having adventures of a very different kind, arming themselves and engaging in combat training. Bonnie was a better marksman than any of the men in the BUC. She and Russell had many weapons stored in their home and practiced putting their children in a cast-iron bathtub to protect them in the event of a shootout with the police.

Russell’s account of this time describes a harrowing near-miss for one of his children. One night, Bonnie was helping one of their comrades make his way to a safe house through streets full of police officers. This man and Bonnie decided they could get through walking casually if Bonnie carried her infant daughter in her arms. Russell’s autobiography explains, “Their plan in case of an emergency was for her to throw the baby on a lawn and for him to hold her as a hostage/shield. It might sound crazy now, but that was the frame of mind that we were all in.”

I wrote him about this episode, wanting to know where a revolutionary draws the line between making a better world for his family and future generations and protecting that family long enough for the children to have a future. I hoped he would tell me what he was thinking that night or in those years. Instead, he replied:

It took me until I was in my seventies to realize just how dominated my life has been by RAGE, HUMILIATION, and for most of that time TESTOSTERONE. YOUTH also played a part until I was able to spend a lot of time reading, and thus being able to better understand life. There is NO way that I can express how DOMINANT RAGE has been most of my life! So much so until it made me very INSENSITIVE to others’ feelings or welfare; including my loved ones and offspring. The RAGE was fed by a deep sense of HUMILIATION.

This struck me as the most honest thing he could have said about not only himself but a period of revolutionary culture that so many have struggled to understand. Russell and Bonnie as a young couple seem not only to have been driven by a revolutionary spirit, fueled by rage and humiliation, but also caught in “the fog of war” – a phrase made famous by former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara to describe impaired decision-making during conflict. When all you see is the war, what the enemy does and what you must do in response, the context falls away, even the things for which you thought you were fighting.

After the shooting in 1970, Russell spent two years underground, traveling incognito through various states and building relationships with fellow travelers, including a group of radical nuns. Bonnie fled with him at first but eventually went back to Philadelphia to care for their children. Meanwhile he was recruiting revolutionaries, raising support, and making connections to like-minded movements around the world.

When all you see is the war, what the enemy does and what you must do in response, the context falls away, even the things for which you thought you were fighting.

In 1972, back in Philadelphia, police following up on a burglary stopped him on the street and found him carrying a large number of weapons. He was then identified as wanted for the 1970 shootings. Facing a new chapter in prison, he steeled his resolve. Looking back on this time, he wrote in 2001:

The martyred Black Panther Fred Hampton once said, to be a revolutionary is to be an enemy of the state. To be arrested for this struggle is to be a political prisoner. I had become a political prisoner of this war that our oppressors had been waging against people of African descent, ever since kidnapping our ancestors from our mother continent of Africa. We had fought back, using every means at our disposal and to the best of our ability; and I had no regrets associated with my action. So, although my situation looked extremely critical and bleak to some, I was determined to remain faithful to the things I had been fighting for, come what may.

III. FORTY-NINE YEARS IN PRISON

There was no question that Russell would try to escape from prison. He was a freedom fighter, after all. Insisting on a distinction between acts of war and the charges for which he was convicted and imprisoned, he viewed himself not as a criminal but as a political prisoner like the imprisoned militants of Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress in apartheid South Africa: “Our resistance, insurrection, and rebellion was seditious, in as much as it was acts of war against an oppressive and unjust authority,” his autobiography explains. Without acknowledging specifically what those acts might have been, Russell rejected the meaning assigned them by the court. He was a soldier in a war against the police, a war he did not start, and held that his activities should be interpreted within that context.

Apparently, the ethos of this war did not lead this combatant to distinguish between individual officers or take into account the context that one of the victims had been simply sitting at his desk and the other had been helpfully offering directions – any more than Rizzo’s police seemed to distinguish between Black people going about their daily lives and those endangering public safety.

If it’s war you want, authorities responded, war you shall have. Over the next five decades in prison, Russell would be beaten and disfigured, drugged to oblivion, denied medical care, and entombed in solitary confinement for a total of nearly thirty years, including the twenty-two he served consecutively. On the outside, his family would be terrorized as well.

Russell’s experience, though extreme, is not unique. Prison is posited as an institution meant to contain and prevent violence, but there is hardly any form of violence in which it is not complicit. Prisons reveal what we as a people are capable of doing to one another, and they prove that we are willing to treat a great many people – over two million of them in the United States alone – as less than human.

Whatever he believed then or now, Russell’s revolutionary actions as a member of the BLA did not free his people or prevent future harm. Instead, they called forth further violence from state institutions in ways that would brutalize the Shoatz family for decades to come.

At Graterford Prison, Russell was reunited with Robert Joyner, his sister Gloria’s partner and a fellow co-founder of the BUC and BLA who was serving a life sentence for the Fairmount Park attack. By this point Joyner had converted to Islam and was calling himself Saeyd. He impressed on Russell his belief that “the primary reason that our collective movement was experiencing these difficulties was due to our failure to lay a stronger foundation in the hearts and minds of ourselves and fellow revolutionaries,” and that Islam was this foundation. At that time, Russell saw himself as a “foot soldier” whose job was to fight to the end rather than hash out ideas. Still, Saeyd invited him to the prison’s Sunni mosque, where Russell was taken with the thoughtful and dignified proceedings. He soon converted and embarked on a study of the faith.

Bonnie brought their children to visit Russell regularly, and she converted to Islam as well. Spiritual leaders from a nearby mosque advised Russell and other incarcerated men to encourage their wives and girlfriends to “marry other men while we were in prison” because “Muslim women should have husbands who can satisfy their needs and desires.” Though Russell was still very much in love with his common-law wife and did not want to lose her, he was swayed by the argument. He informed her of his decision and severed all ties. He would later deeply regret this and realize he had “inflicted a massive amount of harm to the psyches of my loved ones, from which they have not recovered to this date.” Russell would have little contact with the three children he fathered with her until 2014.

Russell’s siblings would sometimes take Thelma’s kids to see their father. At first Theresa did not realize that the place where they visited him was a prison, but she noticed him constantly looking out the windows at the other buildings and the surrounding landscape. In hindsight, Theresa thinks that her father’s main interest in their visits was to take in the view and lay plans for an escape. Russell had not yet learned to be the kind of father he would later become. He was still looking past his loved ones, searching for a chink in the walls that held him.

Becoming Maroon

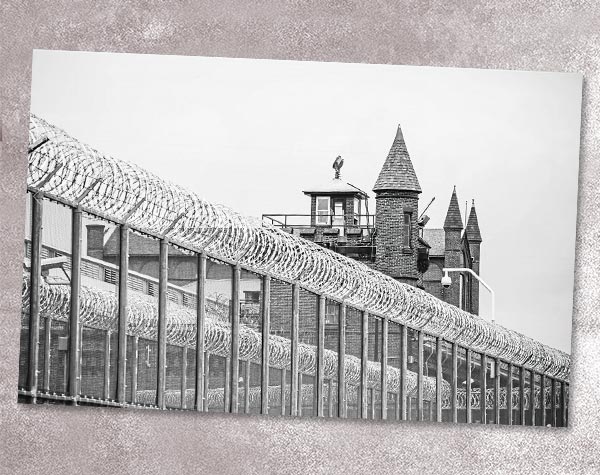

In 1976, Russell was transferred to the State Correctional Institution at Huntingdon, Pennsylvania. The oldest continuously operating prison in the state, Huntingdon was known as the “breaking camp” – the place where the most incorrigible incarcerated men were sent to have their spirits (and not infrequently their bodies) broken. Russell regularly witnessed incarcerated men being clubbed to the floor by staff.

SCI Huntingdon, Pennsylvania: the “breaking camp” Photograph by Andrew Rush/Post-Gazette

Russell and several other men resolved to escape together and put their plan into action on September 14, 1977. They “subdued” four guards, leaving them bound in an empty cell, and used one of their keys to ascend to the roof, then threw a blanket over the top of a barbed-wire fence and climbed to freedom. Russell separated from the others immediately and ran into town until he saw the lights of a police car and hid in a crawlspace under a building. When he emerged, he realized that he had somehow fled in a circle and wound up at the front gate of the prison, where dozens of police cars were gathering to begin an organized search.

Russell backed away quietly, then fled again into the wilds of the Allegheny Mountains, driven by the sounds of the barking hounds on his trail. When at long last the sounds of the dogs moved away from him, Russell sat down behind some rocks to rest and realized that, at least for that night, “I was free!”

Russell used his training from the juvenile detention wilderness camp and the paramilitary exercises he had been doing with the BUC and BLA to survive in the mountains. He laid false trails to throw off the dogs, slept in heavy undergrowth to conceal himself, walked by moonlight, and stayed away from established trails. He was trying to head toward Raystown Lake where he and his comrades had agreed to meet if they should be separated, but once again he realized he was right back where he started near the prison. He decided to lay low where he was. For sustenance, he foraged for vegetables in local fields and at one point caught and ate a turtle raw. Despite the physical hardship, Russell found quiet joy in his life in the mountains. “I was often cold and hungry, but I felt immeasurably better off than when I was in prison.”

Eventually, to gain some distance from the prison, he made a series of attempts to commandeer a vehicle, at one point leaving Dale and Marlene Rhone and their young son tied to a tree for hours after trying to steal their car, which he abandoned when it failed to restart. In another attempt, with a gun he took from the Rhones’ home, he shot two bullets into a driver, Jack Powers, who got away. Finally, he took over the car of a man named Calvin Reddings and forced him to try to speed around a police roadblock. Reddings instead leapt out of the moving car and yelled, “I’m a hostage!” Assuming Reddings to be an accomplice, the police shot at him and surrounded Russell, handcuffed him, and put him in a car where a state trooper held a shotgun under his jaw. Of this moment, Russell wrote in 2001, “Alas, the chase was over. I had been a runaway slave, but I was captured and was being returned to the plantation. It had been twenty-seven days.”

Unsurprisingly, Russell’s escape was received very differently inside and outside the prison. The local community, terrorized by the hostage-taking, was outraged. Russell had escaped a prison where he had been traumatized only to do the same to others. Many other incarcerated men saw in him the spirit of their ancestors who had escaped slavery, and they renamed him accordingly. When Russell had become a Muslim, he had taken the name Harun Abdul Ra’uf. Someone remarked that the police had chased Russell “like a maroon” – a term describing fugitive slaves. Maroon sounded like Harun, and the name stuck.

When he started publishing political essays, he used the name Russell Maroon Shoatz. Across the years that followed, he researched the history of maroons around the world and their valiant struggles to win and maintain their freedom. The word maroon, as defined by the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, evokes several other meanings applicable to his life:

- to put ashore or abandon on a desolate island or coast by way of punishment …

- to place in an isolated and often dangerous position

- to abandon and to leave without aid or resources

As a noun, the word refers to a person abandoned and isolated in this way as well as to escaped slaves, “especially in mountainous areas.” The irony that strikes most forcefully lies in the fact that the historical maroons stayed free or died trying, while Russell Maroon Shoatz would spend three decades in solitary confinement. Yet his adopted name is a sign of belonging to a much larger community of captives who are determined to be free.

Aftermath of the Escape

By 1977, Thelma and her children were living in a home across the street from Philadelphia’s Samuel B. Huey Elementary School, where she worked and they were students. Theresa, then thirteen, had known all along that her father was in prison, and “it wasn’t a bad thing, although I knew no other kids that had a family member in prison. It wasn’t until my dad escaped from a prison he was at that I knew something’s wrong.”

As the family walked to school that morning, a reporter approached them, saying that Thelma’s husband had escaped from prison and was rumored to have been seen in a nearby park. Thelma thought, “Oh my God. This is all I need.” Helicopters began circling overhead.

The family arrived at school only to have it shut down and surrounded by police and FBI, presumably on the assumption that Russell would come there to see his children. All of the school children were evacuated from their classrooms but were not allowed to go home. The students and teachers crowded into the school yard, fenced in and staring at Thelma’s house.

Thelma’s children could see their mother, fearful and frantic, at the door to their home with police and FBI all around her, pushing their way inside, where they destroyed furniture and photographs and nearly shot the cat. They ultimately found nothing to aid them in their search for the fugitive Russell, who never had any intention of approaching Philadelphia or his family while he was on the run.

Now all of the Shoatz children’s teachers, classmates, and classmates’ families knew about Russell and had decided opinions about him and his family. The children were marked. Theresa was teased mercilessly by peers and teachers alike. Russell’s mother tried to help protect her granddaughter from this toxic climate by arranging for Theresa to go to other schools, but the family trauma would inevitably follow her.

Russell III also struggled to process what was happening. At ten, he hadn’t given his father’s incarceration much thought prior to this incident, but watching the police raid his home shifted something in him. Though he bore no responsibility for his father’s actions, police officers he met usually made sure he knew they recognized his name. Still, during elementary school and beyond, teachers and other loving adults in Russell III’s life supported him, particularly Papa Barnes.

After the 1977 raid on their home, Thelma and her children slowly worked to restore the peace in their lives, never imagining that in three short years Russell would upend their world again.

Upon his re-arrival at Huntingdon, Russell was taken to an isolated area in the solitary confinement wing and beaten by prison staff, sustaining such severe damage to his testicles that he continues to suffer from the injury today. After this beating, Russell was kept in solitary confinement, where the guards engaged in an organized regime of harassment and abuse: “constantly coming by the cell and offering threats, keeping the lights on day and night, keeping the cell freezing cold and constantly tampering with the meager food I was given. At one point I was given a sandwich that had a heel print, with the face and paw of a cat impressed on it.”

Multiple times each week, several guards would don riot gear, spray mace into a cell, beat its occupant, drag him down the tier so the others could see, and deposit him in an isolation cell in the basement.

On the intervention of his lawyer, Maroon was transferred to a state prison in Pittsburgh with the promise that he would not be returned to Huntingdon, but the conditions there were similar. Russell reports that the staff kept “the level of terror so high that it would offset any ideas that any of the men were getting because of my near successful liberation attempt.” Multiple times each week, several guards would don riot gear, spray mace into a cell, beat its occupant, drag him down the tier so the others could see, and deposit him in an isolation cell in the basement. The guards would tell Russell that their colleagues at Huntingdon had asked them to “take care” of him at their first opportunity. They so frequently left cigarette butts, insects, or their own spit in his food that Russell ceased eating anything that he could not buy himself from the commissary or have bought for him during visits with family and lawyers. Because he refused to eat the standard prison-issued meals, Russell received the designation of “psychiatric observation prisoner,” which meant that the authorities could force him to take psychotropic medication without his consent.

After about a year of this treatment, Russell had lost considerable weight and was suffering from the stress. He started a physical altercation with his own attorney in court, which led to a judge ordering him sent to the state mental hospital for evaluation. This would become the site of his second successful escape.

Back to the Mountains

In 1978, Russell arrived at the Fairview State Hospital for the Criminally Insane. A Pulitzer Prize–winning series in the Philadelphia Inquirer about Fairview in 1976 revealed widespread abuse of patients at the facility. The “Fairview Findings,” as the articles were called, offered evidence of overcrowding, patients beaten to death by staff, and the indiscriminate use of psychotropic medication to control behavior. Russell arrived shortly after this exposé and recalls that during his first months there, current and former members of the staff were in the process of being tried for crimes ranging from embezzlement to the murder of patients.

Russell’s fellow patients – most of whom had no criminal convictions but also no other options for treatment – described the commonly used “shoe leather treatment” which involved stomping a noncompliant patient into submission or death. Because of the recent investigations, the beatings became less frequent and the extreme use of medication to control behavior had become standard practice. What the staff called “chemotherapy” kept patients nearly comatose.

The drug chlorpromazine, an antipsychotic marketed under the name Thorazine, was developed in 1954 for the treatment of hallucinations and aggressive outbursts in schizophrenic patients. Thanks to efforts to reduce mental hospital populations in the 1960s and 1970s, more and more mentally ill people wound up in prisons rather than hospitals, and Thorazine’s use became widespread, even as its debilitating side effects became well-known. The use of Thorazine to pacify and control incarcerated people, particularly those connected to the revolutionary movements of the 1960s and 1970s, is well documented.

Russell’s nightly dose was administered at 8 p.m., and he would stumble through the next morning, not feeling like he had regained clarity and equilibrium until about 1 p.m. He watched other men lie on benches in a semicomatose state all day long and feared that this would be his future if he remained medicated. One night after taking Thorazine, Russell fainted. He had been given an overdose. Russell spent two days in intensive care. After this, when his nightly doses began again, he devised a way to hold the medicine in his mouth and then secretly spit it out.

By this point, Russell had become romantically involved with a young college student named Oshun (legal name Phyllis Hill), who visited him regularly to talk about Black liberation. Together they began planning an escape and enlisted the help of Russell’s friend and fellow patient Lumumba (legal name Clifford Futch). Oshun started stockpiling weapons.

On March 2, 1980, Oshun came to visit wearing heavy winter clothing that concealed a submachine gun and a revolver. Russell and Lumumba used the weapons Oshun had brought to force patients, staff, and visitors against the wall and make their escape. Oshun led Russell and Lumumba to a place where she and her friends had deposited provisions to last them a month in the wilderness. The trio packed all of their gear onto a sled and headed through the snow into the Appalachian Mountains. The plan was to stay away from all contact with other people for about a month and wait for the authorities to call off the search. Eventually, a friend would deliver a car that they could drive to a new life underground.

After two nights of camping in the snow, several of Lumumba’s fingers showed signs of frostbite. The group realized they might have to head back to civilization to find medical treatment. Meanwhile, a trapper spotted Russell and alerted the police.

The three fugitives fled with their guns up the mountain to an outcropping of rocks that could serve as a kind of bunker. The crackle of police radios soon alerted them that their pursuers had arrived. The fugitives opened fire, which the police returned. Chunks of bark dislodged by bullets rained down into the bunker. The authorities offered to send a reporter, a lawyer, or an FBI agent to talk to them, but Russell rejected each attempt at negotiations. About two hours into this standoff, Oshun told Russell and Lumumba she was ready to surrender. They called out to the authorities to hold their fire so she could emerge with her hands up. Once she was out in the open, unarmed, a negotiator demanded that Russell and Lumumba surrender as well. They decided they had to do so or risk watching Oshun be gunned down. They joined her with their hands raised.

As reporters and police buzzed around them, Russell discovered that the police had set up an ambush right behind their bunker. If Oshun had not led them to surrender when they did, they would almost certainly have been killed by a volley of bullets from behind. More than fifty police and FBI agents had been involved in the shootout. Miraculously, no one had been injured or killed.

Organizing from the Inside

Russell and Lumumba were sent to solitary confinement at the State Correctional Institution at Dallas, Pennsylvania, where they went on a hunger strike in an attempt to get transferred into the general population. Six or seven other men joined them for a time. The authorities shuffled the two through several moves to county jails and back to Fairview, keeping them at separate facilities in an attempt to break their resolve. Eventually, they both landed back in solitary at SCI Dallas, where they again rallied other men to join them in the hunger strike, which ultimately lasted for fifty-five days. Russell and Lumumba decided to call off the strike before it killed them, but not before Russell had once again demonstrated that he was both strong-willed and inspiring to other incarcerated men.

Oshun spent time in a county jail in Philadelphia where she was housed with women from the MOVE political organization (whose residential headquarters would be bombed a few years later in 1985 by the Philadelphia Police Department, killing six adults and five children). She agreed to a plea deal that would give her a reduced sentence if she agreed to keep a low profile with the media. The New York BLA had freed Assata Shakur from a prison in New Jersey in late 1979, and the authorities did not want another revolutionary Black woman to capture headlines. Oshun was not required to testify against Russell and Lumumba. She served just under three years in prison for her role in their escape.

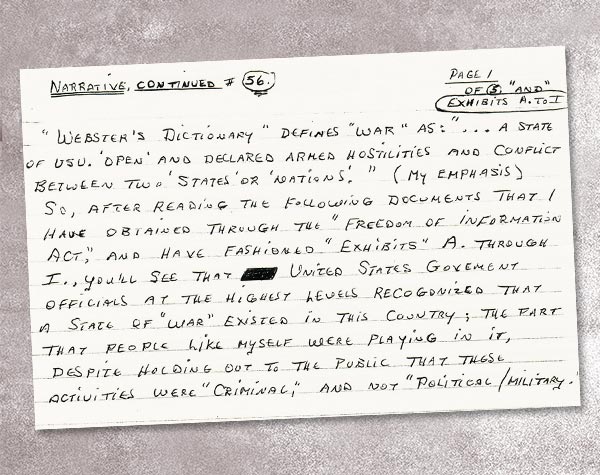

Russell and Lumumba decided to represent themselves in their court cases. At trial, Russell summoned Philadelphia police and FBI agents to testify about his long history of political actions. He used the Freedom of Information Act to obtain copies of FBI documents showing that J. Edgar Hoover’s Bureau had kept a file on him and targeted him as an urban guerrilla. These tactics did not ultimately sway the jury, however, and he received his second life sentence. Lumumba met the same fate. The two were returned to SCI Dallas and placed in solitary confinement with no clear end date. Their cells were searched by guards every day, despite the fact that they had no contact with anyone who could bring them contraband. This went on for more than a year.

Russell Shoatz's 1980 court filing in his own defense arguing for status as a prisoner of war Photograph courtesy of Russell Shoatz

One day another man in solitary, Sly, refused to be handcuffed so that the guards could administer his cell’s daily search. A squad of officers in riot gear attacked him and dragged him, covered in blood, down to an even more isolated part of the prison, known as the dungeon. This event caused such a stir among the men in solitary that they demanded to see a shift commander to register a complaint. When this went nowhere, Russell led the men in a riot. In the fight, prison staff nearly cut off one of Russell’s fingers. Russell was handcuffed, beaten, stripped naked, hauled to the dungeon, and left for several hours. A medical attendant came later that evening and sent Russell to the prison hospital, where his finger was stitched back in place.

Russell was transferred yet again to solitary at Pittsburgh, where he began another hunger strike that others joined. In court, a lawyer successfully argued that the charges against Russell and the other rioters should be dismissed because they had been consistently terrorized by the guards.

After this victory, Russell discovered that the men at Pittsburgh had taken up the hunger strike again and devised a strategy to keep it going for long periods of time. Two or three men would refuse to eat for about twenty days before another set of strikers would take over. In the meantime, those who were eating would write letters to activists and media outlets to draw attention to the plight of those in perpetual solitary confinement. This enabled the men to collectively maintain the hunger strike for about a year and attract the attention of the host of a radio show, the NAACP, and enough activists to hold several demonstrations outside the prison. After the prison banned people who had been seen protesting from visiting their incarcerated loved ones, activists staged a march where everyone wore ski masks to protect their identities. Prison administrators eventually relented, allowing protesters to visit their loved ones again and moving out all of the men who had been held in indefinite solitary confinement.

As soon as Russell was released from solitary confinement, he began organizing men serving life sentences into a political body. Lifers and those with decades-long sentences tend to stabilize any prison population because they have reason to invest in their community’s well-being across time. Even compared to the rest of the United States, where sentences tend to be harsher than those in other countries, Pennsylvania is extraordinarily punitive in its sentencing. Russell had the misfortune of being not just from Pennsylvania but from Philadelphia County, which has sent a higher proportion of its people to prison for life without parole than the overall incarceration rates of 140 nations.

In March 1982, the men at SCI Pittsburgh formed an organization called the Pennsylvania Association of Lifers (PAL) with the goal of lobbying for the end of life without parole sentences. The organization grew from twelve members to one hundred after Russell got involved, and when they held their first election, Russell was unanimously chosen as their president. At the same time, PAL voted in a board of directors. A few hours after the votes were tallied, Russell and the entire board were rounded up by guards and sent to solitary. The lifers were prepared: they had documentation that they had formed their group in compliance with all prison regulations on the creation of inmate clubs. According to Russell, guards ransacked the cells of all the men they had just placed in solitary and destroyed all paperwork they found. However, he had anticipated this possibility and left a copy of PAL’s papers with a man who was not on the club’s board. When the prison charged Russell and the rest of the PAL leadership with holding unauthorized meetings, this man produced the necessary records to refute those accusations.

The authorities then changed tactics and accused Russell and the board members of creating PAL to conduct illegal activities inside the prison. Though no evidence was presented to corroborate these charges, Russell and his colleagues were all punished with six months in solitary. The original election results were discarded, but while their leadership sat in solitary, the voting lifers responded by reelecting Russell and selected temporary appointees to carry out PAL’s activities until its leadership returned to general population. The lifers engaged a lawyer and even sued the prison administration when it once again disbanded the organization, but lost in court.

To judge by the harsh response, nothing Russell had done in his life until now posed such a threat to Pennsylvania’s prison system as did his role in democratically and legally founding an inmate club. Neither his physical attacks on prison staff nor his multiple escapes brought about such a sustained and relentless regime of punishment. Russell’s time in solitary became an indeterminate sentence with perfunctory reviews and rejections every thirty days. He would not find any relief for the next seven years, and when he did, it came because the authorities erroneously concluded that he was involved in instigating a prison rebellion at SCI Camp Hill about which he had no knowledge and which happened over two hundred miles away. Though he played no part in the rebellion, Russell was flagged as suspect and sent to the US federal prison in Leavenworth, Kansas.

This proved fortunate. In Leavenworth, federal authorities moved Russell out of solitary confinement and into the general prison population after his supporters challenged Pennsylvania’s claims about his involvement in the Camp Hill riot. For a little over a year, he had a welcome respite from life in solitary, was able to see much more of his family, and met many other incarcerated revolutionaries, including Leonard Peltier of the American Indian Movement, Sundiata Acoli of the BLA, and Phil Africa of MOVE. These months in the federal system would be Russell’s last taste of regular social interaction for more than two decades. When the Pennsylvania state authorities had him moved back into their prisons in 1991, they put him back in solitary and almost literally threw away the key. He would remain in perpetual solitary confinement for the next twenty-two years.

The Hole

The inciting incident for Russell’s first seven-year stretch in “the hole,” as both guards and incarcerated people refer to solitary confinement, was not one of his escapes but rather his election as president of PAL; presumably, the next twenty-two years were simply a continuation of this punishment. The Pennsylvania Department of Corrections continued to conduct perfunctory reviews of his status while offering no hope that it would be lifted. In 2013, after Russell had spent more than two decades in solitary, the prison superintendent justified keeping him there because, as Victoria Law wrote in The Nation, he had been a part of “radical militant groups, his former association with the Black Panther Party, and his current political views and activities via mail and phone, his ability to organize others.” None of these arguments had ever previously been presented to Russell, his family, or his lawyers, who believe that prison authorities saw Russell’s leadership capacity and political beliefs as more threatening than his past actions.

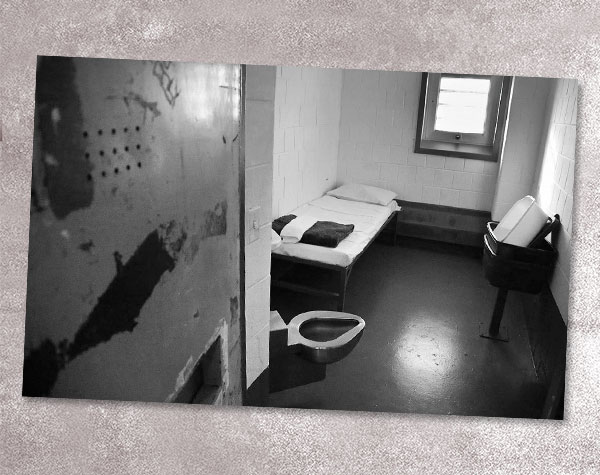

Russell’s life in the hole consisted of twenty-three hours locked in his cell each day, with the lights always on. He could leave only to take a ten-minute shower three times a week and go to an enclosed cage by himself for one hour five times a week. The cost of each foray out of his cell was to be strip-searched, handcuffed, and shackled. Russell’s family could visit him for one hour per week, driving seven hours each way to speak to him through Plexiglas. Russell could receive letters but could not have books or periodicals mailed to him. He could not keep personal books with him beyond legal materials and one religious text. He could request up to two books per week from the prison library, but he could not read anything not already owned by the prison.

A solitary confinement cell (Rikers Island, New York). The size of the cells in which Shoatz was held continuously from 1991 to 2014 was ca. 64 to 80 square feet. Photograph by Bebeto Matthews/Associated Press. Used by permission.

Despite these constraints, Russell embarked on an energetic project of self-education. He dove into anything that he could get his hands on – “economics, education, entertainment, labor, law, politics, religion, and warfare” – particularly anything that touched on liberation struggles throughout history. In the early years, he organized seminars in his cell block to discuss these readings and ideas, which even included “more than a few prison guards – once they got over the idea that we prisoners could not intelligently interact with them.” Though, being in solitary, participants had to remain in their cells, they hollered up and down the hall and passed around handwritten missives by “fishing lines” through the bars.

“As the hardened young men would be sent to the hole, my comrades and I would immediately engage them about why they were in prison and stress how important it was that they educate themselves before leaving. It was literally a mental boot camp,” he writes. Like his long-ago gang interventions, “As part of my mission I have also dedicated my life to trying to help guide the youth of the present generation away from the traps that ensnared me, and helping them find their own mission in life.”

An unexpected result of all this was that he discovered the writings of radical feminists that caused him to realize how much of the world and his own view of it was founded in misogyny. He had flattered himself that he left this behind after his gangster days, but, as he wrote in a 2010 essay, “after becoming politically conscious, I further deluded myself into believing that being a ‘revolutionary’ made me a champion dedicated to the uplifting of all humanity. It turned out, however, that I had just transferred many of my woman-hating practices to another arena. That’s the special fate of male revolutionaries who put so much stock in the testosterone-dominated armed struggle.” He applied himself to a serious self-examination and heartily recommended “matriarchal” philosophy to others.

As the years went on, the walls closed in. He was transferred to SCI Greene, a new “supermax” prison with a “control unit” designed to inflict sensory deprivation, with solid doors sealed against fishing and soundproofed against hollering. The rules were tightened and more harshly enforced, and the literature available to read was drastically reduced. Russell and company creatively responded to these new conditions by writing out their thoughts and mailing them to supporters on the outside, who in turn mailed them back inside the prison to the intended recipients, but once this practice was discovered the mail room put a stop to it. Even then, Russell continued writing essays for the outside world, but he felt acutely the loss of this last form of human interaction.

Russell has cumulatively spent nearly thirty years in solitary confinement, which he describes as “social torture paid for with tax dollars.”

Year after year in the hole sent Russell into profound spirals of depression. He could not get out of bed some days and spent much time contemplating ways to kill himself. Ultimately, the only reason he did not end his life was that he had no way to do so.

Juan Méndez, the former United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture, asserts that more than fifteen days of solitary confinement constitutes torture. Méndez interviewed Russell in 2015 and characterized the conditions of his life in the hole as “cruel, inhuman, or degrading punishment under customary international law standards.” Russell has cumulatively spent nearly thirty years in solitary confinement, which he describes as “social torture paid for with tax dollars.”

In 2013, Russell filed a lawsuit to end his indefinite isolation and was released into the general population in 2014 on the condition that he not do any further political organizing. He was awarded a $99,000 settlement in 2016 for his pain and suffering in solitary. Russell divided the settlement money between Thelma and Bonnie, the mothers of his children, in a highly delayed form of child support. Even now, he says, he is still learning to be a father and grandfather.

Parenting from Prison

All of Russell’s seven children are now in their fifties, and each of them has had to get to know him through prison visits, letters, and brief phone calls. Russell makes the most of these opportunities and loves interacting with his children, who have impressed him by becoming accomplished and caring adults despite, or perhaps because of, their challenges in life.

Theresa takes pride in the lessons she has learned from her father and has repeatedly sought his mentorship. She credits her father with encouraging her to take in twenty-eight foster children and to create afterschool programming for students with incarcerated parents. She was venting to him about kids acting out at the school where she worked, and he prodded her, “Why don’t you do something about it?” He told her to be for them what she had needed somebody to be for her while he was gone. “I ended up loving those kids like my own,” she says.

If these authorities pride themselves on how well the system works, that is because they have defined justice in their own terms without asking Thelma or the Shoatz children what justice might look like in their lives.

As an adult, Russell III got to know Russell chiefly through political and intellectual debates as they sat together in prison visiting rooms. “These conversations with my father have been like mentally battling one of the greatest mixed martial arts fighters of all time,” he says, a one-on-one reprise of Russell’s seminars with other incarcerated men. The two have challenged each other and grown in their respect for the other’s perspectives, even when they disagree. Russell III came to understand the youthful version of his father as “ready to dedicate his life to the movement, to the salvation of his people.”

Russell III does not believe that the BLA’s violent tactics were effective or morally sound. He believes that Black people and others who endure incarceration, injustice in the courts, and police brutality and murder have the right and need to respond, but that more violence will not solve this problem. He said in a 2020 joint interview with his father:

I’ve spent forty years learning from my father’s struggles. We don’t see eye-to-eye on all topics related to our people’s fight for liberation. But when it comes to character, courage, commitment, and critical thinking, I must admit that those disgruntled teachers, authority figures, and police officers from my youth were spot on: I have proudly ended up being just like my father – and my father deserves to be free.

Russell III and his sisters have devoted much of their adult lives to seeking their father’s release. They have led teams of activists, lawyers, scholars, artists, and figures in popular culture – among them Chuck D, Mos Def, and Colin Kaepernick – to lobby for him.

In recent years, Russell has had reason to feel greater urgency about both his liberation and his ability to connect with his family. He has a terminal cancer diagnosis and knows he will not receive adequate health care as long as he remains in prison.

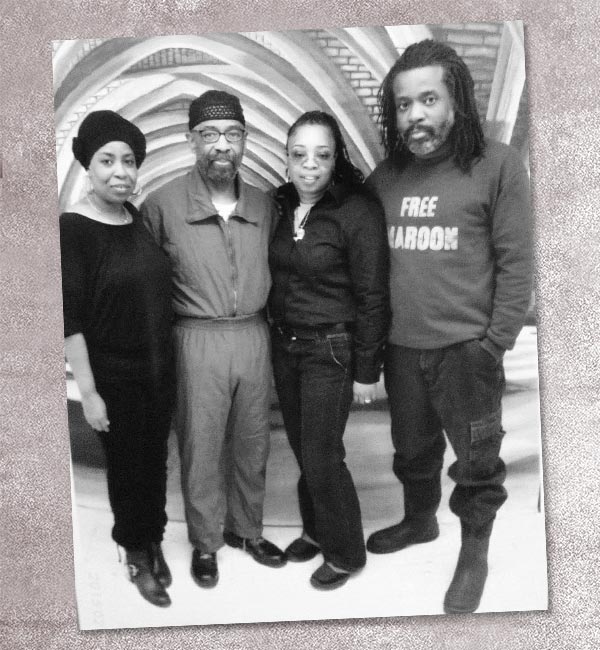

Members of the Shoatz family visit their father in prison, ca. 2014. From left: Theresa Shoatz, Russell Maroon Shoatz, Sharon Shoatz, and Russell Shoatz III. Photograph courtesy of the Shoatz family

People in prison have the right to receive medical treatment, but they often cannot access it. The Prison Policy Initiative found that “mass incarceration has shortened the overall US life expectancy by five years.” Russell’s cancer led to the removal of both his upper and lower intestines. He now lives with a colostomy bag and has endured several debilitating rounds of chemotherapy. Meanwhile, he caught and survived Covid-19.

In April 2021, he was informed that his cancer was aggressive and terminal, and that the prison would not offer him palliative treatment. He appealed for a medical release to live out his few remaining days with his family, and the court denied him on August 12, 2021. When I received this news, all I could think was of Toni Morrison’s refrain in Song of Solomon: “Everybody wants the life of a Black man.” When I emailed my condolences to Russell, he responded with the indomitable attitude that is characteristic of him, insisting that he would petition the court again at a later date.

Reckoning with Violence