Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Child of the Stars

-

Refugee Letters

-

Life in Zion

-

How to Run a Cemetery

-

Integrity and the Future of the Church

-

Daring to Follow the Call

-

Poem: “For the Celts”

-

Poem: “Wreathmaking”

-

Poem: “The Hunger Winter, 1944–5”

-

Editors’ Picks: The Cult of Smart

-

Editors’ Picks: The Utopians

-

Editors’ Picks: The Lincoln Highway

-

Casa de Paz

-

The Pilsdon Community

-

Letters from Readers

-

Nonexistence Does Not Scare Me

-

Toyohiko Kagawa

-

Covering the Cover: Beyond Borders

-

Choosing America

-

Church as Sanctuary and Shelter

-

Northern Ireland’s New Troubles

-

When Migrants Come Knocking

-

The Florentine Option

-

Three Kants and a Thousand Skulls

-

The End of Rage

-

Telling a Tale of Two Fathers (Video)

-

Home Is Not Just a Place

-

The Quest for Home

In Search of Lost Fig Trees

Can our memories bring us back home? A mosaic of fathers and daughters, Damascene chocolates, and the poetry of Naomi Shihab Nye.

By Stephanie Saldaña

September 29, 2021

1/

In 1950, Aziz Shihab, a young Palestinian journalist, arrived by boat in New York. From his passport photo, we can picture him: his dark, wavy hair, round glasses over his deep brown eyes, wearing a suit and jacket. He had received a scholarship to attend university in Kansas, where he would soon begin an extended career in writing. On the surface, he was very much an immigrant. But he was also a refugee, expelled with his family from their home just outside the walls of the Old City of Jerusalem in 1948 – his family fleeing to a village in what is today the West Bank. The loss of his home haunted Aziz for the rest of his life. So would the tension of being both immigrant and refugee; of seeking out a new life and longing for a lost one. As the boat approached New York Harbor, Aziz Shihab threw his suitcase overboard; it was never clear exactly why.

In Arabic, his last name means “shooting star.” In the following decades, Shihab would reflect on his sense of exile in newspaper articles, a cookbook called A Taste of Palestine, and a memoir about his return to be with his mother on her deathbed. Yet he would become most famous as the subject of his daughter’s poems. In Naomi Shihab Nye’s work he appears over and over again, until he becomes as familiar to us as the gentle pull of her voice. Her father, recounting traditional stories about Joha next to her bedside. Her father, singing Arabic in the shower. Her father, hit by a stone on the head as a boy. Her father, preparing thick Arabic coffee. Her father, calling out for home until the end.

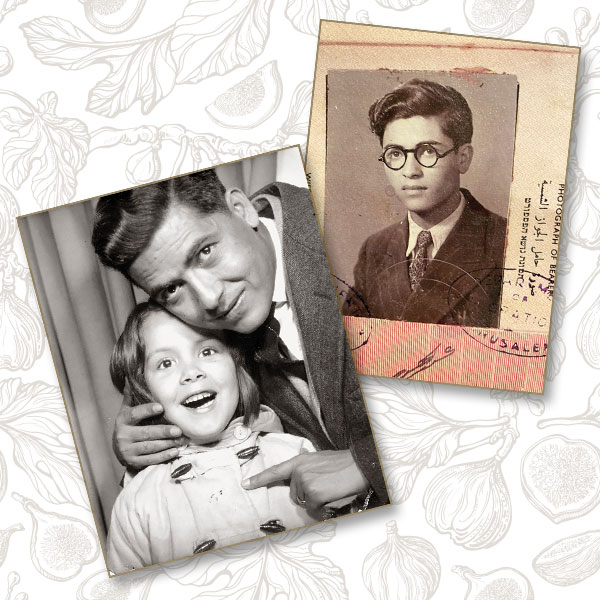

Top, Aziz Shihab, passport photo, ca. 1950; Bottom, with his daughter Naomi, 1960 All photographs courtesy of Stephanie Saldaña, Nour Al Ghraowi, and Naomi Shihab Nye

In one of her most famous poems, “My Father and the Fig Tree,” Naomi Shihab Nye recounts the story of her father obsessively searching for figs in America, trying to explain their magic, as though the very touch of them might transport him home. She writes:

For other fruits my father was indifferent.

He’d point at the cherry trees and say,

“See those? I wish they were figs.”

The children of refugees wrote to Naomi, understanding. She recounts in her introduction to her father’s cookbook that the letters would say: “For my father it was a plum tree,” or “My father felt exactly that way about a grapefruit tree.”

But all this would come later: the books, the letters, the poems. For a moment, let us return to Aziz Shihab’s arrival in New York. It is not only a new country: it is as if the world as he has known it has been pulled from beneath his feet. He writes letters home to his mother to tell her that he has safely arrived.

He only learns later that he has been mailing them into trashcan slots.

“It was just that sense of no gravity,” Naomi tells me when I interview her about his arrival. “What is a mailbox? What is a trashcan?”

2/

If I am writing about Aziz Shihab now, more than seventy years after his arrival in New York, it is because, in a way I’m still not sure I understand, he became a friend. I never met him. Still, he followed me, as I followed him.

From New York, Aziz traveled to Kansas, where he enrolled in university. Years later, the owner of a drugstore soda fountain there would tell Naomi that her father, a regular, always looked preoccupied sitting at the counter. “Well yes,” she would write in her book 19 Varieties of Gazelle: “That’s what immigrants look like. They always have other worlds on their minds.”

From her poems, from his writings, and from Naomi herself, I try to piece together some details of what Aziz’s “other world” had once been. Born in Jerusalem, Aziz Shihab grew up in the Nabi Daoud quarter just outside the Old City walls. I know the house, near the tomb of King David, built of stone with arched windows overlooking the road to Bethlehem. At the time, Jerusalem remained under British control. Aziz attended the Rashidiya school for boys, near Damascus Gate on the opposite side of the Old City; every morning he crossed the Old City, alleys and spices and archways working their way into his breath, becoming part of his being. He loved the multicultural fabric of Jerusalem. A Muslim, he watched Christian pilgrims walk to Bethlehem, his father allowing him once to join, insisting he wear his best suit. He played with his Jewish neighbors. He taught himself English, becoming so fluent that he was eventually hired by the BBC to read reports on the radio.

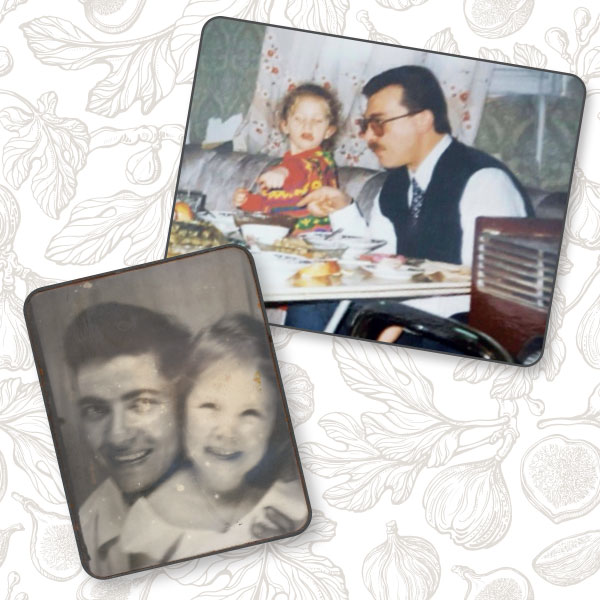

Top, Nour Al Ghraowi with her father, 1997; Bottom, Naomi Shihab Nye with her father, 1956

Then, just as quickly, his entire world was gone. Or taken. The details are unclear: how he and his family were forced from their home at gunpoint in 1948 during what Palestinians call the Nakba, or “Disaster,” and Israel refers to as the War of Independence; how they “escaped with the clothes on our backs and our house keys.” Aziz found his way to a part of Jerusalem under Jordanian control, renting a room in the Old City and working as a journalist. He climbed the walls of the ancient city, where he had a view of the home he’d lost.

His friend was killed beside him, a subject he never wanted to speak about. “He would completely shut down, and our mother told us never to ask him about that,” Naomi tells me. “I always felt his homesickness.”

Later, when he moved to Kansas, Aziz learned that many Americans misunderstood his lost homeland, as well as his Muslim faith. He introduced himself as a refugee from Jerusalem. He was going to return one day. That was how he spoke of himself when he met Miriam Allwardt, who would become his wife.

3/

Naomi Shihab Nye was born in 1952 in St. Louis. She remembers her father telling her, on a Mississippi River boat trip: You know, I did something once from a boat. I threw my suitcase.

“I never liked that story when I was a child,” Naomi tells me. “How could you throw your stuff away? And what else was in the suitcase? Why did you do that?”

Even then, she knew there was something different about her father. He asked lots of questions. He told stories – every night, if he wasn’t at work late, he would tell her stories by her bedside.

When she was fourteen, they moved to Jerusalem for a year; she walked her father’s streets until they became part of her being, an experience that would find its way into her poems and novels for decades. But they didn’t stay. When Naomi was seventeen, her family moved to San Antonio. Now, she, like her father, was also between worlds.

In her poem “Museum” she tells of her arrival in San Antonio, where she read about the McNay Art Museum, located inside an old mansion. She and her friend Sally decide to go see the famous paintings. They arrive, wandering from room to room, admiring the art, until someone behind her asks: “Where do you think you are?”

They are not in a museum at all, but in someone’s house.

For years, she didn’t tell anyone. Mailboxes. Trashcans. Museums. All of us, every now and then, losing the ground beneath our feet.

4/

My father, Steven Saldaña, was born in San Antonio in 1950, around the time Aziz arrived in New York. His family had lived in the city for generations, and for as long as I can remember, San Antonio was described in our household simply as home – the place where my father knew each street, and could recognize cardinals landing on branches, and called everyone by name. Still, much remained unspoken in our family, beginning with the ñ we never put in our last name, the Spanish of my grandparents that my father did not speak. As a child, he dressed up as Superman, the ultimate outsider, a refugee from Krypton, concealing one identity and living another.

Childhood photo of Steven Saldaña, the author’s father

When my parents married, they migrated north to Kansas, where I was born. Soon, we moved on to Missouri, where my father worked at a local Sears Roebuck, and took us sometimes to St. Louis to ride the boat on the Mississippi River.

When I was ten, my grandmother, sick with cancer, called us back to San Antonio. So we returned “home.” My father pointed to butterflies. Bluebonnets in season.

He whispered at my bedside: “Fly. Fly far, far away.”

5/

I was perhaps fifteen years old the first time I met Naomi Shihab Nye. In San Antonio, she was always referred to simply as “our poet,” for she was so rooted in the city – speaking in schools, teaching children – that we could not imagine she had ever lived elsewhere. That year, I attended a poetry reading at the University of Texas in San Antonio. The poet that night was W. S. Merwin, the great translator of the natural world. I had met Merwin the year before; he came to speak to me while I was sitting beneath a tree. He was, surreally, wearing a necklace of moss around his neck, and had just finished reading at the San Antonio Book Fair. We remained in touch. Now he had returned.

The reading ended. I walked beside Merwin through the campus. Naomi Shihab Nye, long his friend, was on his other side.

“Weren’t you afraid to speak in front of all of those people?” I asked Merwin.

He turned to me, his blue eyes meeting mine, and said: “Stephanie, you must never be afraid of anything.”

6/

Years passed. I heeded my father’s whispers, and moved far, far away, arriving in Damascus to study Arabic. I crossed the Old City streets until they became part of my being. I learned what it is to love a place that is misunderstood. When I returned home to Texas, I always carried the same gift: the famous Syrian chocolates created by the Ghraoui/Ghraowi family, known in the Middle East as among the finest chocolatiers in the world. I relished the ritual of visiting the store in Damascus, where the staff patiently waited on me as I chose every piece of handcrafted chocolate, carefully wrapped, each more delicate than the last.

By the time I arrived in Texas, I felt too tired to explain: In Damascus, light falls on stone. The people are kind. They’ll invite any stranger to coffee. They’re musicians. Artisans. I’ve never met people who pay such attention to beauty.

So instead, I opened the box of chocolates. Here. Taste this.

7/

In Syria I fell in love with a man from France, and we married. In 2006, we moved to Jerusalem. The following year, Aziz Shihab died. “Are you home now?” Naomi asks him at the opening of her book of poems, Transfer.

My father, by then president of Catholic Charities in San Antonio, began helping to resettle refugees from all over the world. Maybe it was that memory of Superman. Maybe he hoped that someone was taking care of me, too, on the other side of the world. Maybe there was a side of my father I’d never imagined. He worked tirelessly, and men and women from Sudan and Iraq and Afghanistan and Iran settled in our streets. They’ll feel at home here, my father explained to me. Knowing that Naomi’s father had also been a refugee, my father reached out to her, asking her to help him at charity events.

So they became friends, and my father was soon convinced that Naomi could somehow connect him to me, bridging the distance between us. In 2008, he gave me two books for Christmas. The first was Naomi’s book of poems about the Middle East: 19 Varieties of Gazelle; inside, my father handwrote me a letter: Stephanie: Thank you for opening the world to me …

The other volume was Aziz Shihab’s cookbook of recipes and memories.

I settled into my home in Jerusalem to read. That is how I learned that I was living in the neighborhood where Aziz Shihab had walked every day as a boy before his exile. His school stood around the corner from my home.

So I began to walk in his footsteps. Past the school. Through the market. In front of the Church of Gethsemane, where he had played with friends. I remember you. I remember you.

8/

My father died in 2012 after a terrible battle with cancer. At home for the funeral, I found his copy of Aziz Shihab’s memoir: Does the Land Remember Me?

Naomi had written inside: “To Steve. From the daughter of Aziz.” I carried it back with me to Jerusalem.

I visited home only once after that. Naomi met me in a coffee shop, and we spoke of our fathers. Two grieving daughters. A sense of no gravity.

By then Syria had erupted into civil war. The United States closed its doors to almost all refugees. I traveled the world, seeking fragments, as Syrians scattered across the globe. In Paris, a man from Aleppo still making soap. In Amman, Syrians pounding pistachio ice cream.

I searched for the chocolate. I discovered that the branch of the family that spelled their name Ghraoui had opened a chocolate shop in Budapest. Their cousins, who spelled it Ghraowi, opened a store in Corpus Christi, Texas. This seemed impossible.

I couldn’t bring myself to visit. It would make the war real. In any case, before long, the chocolate shop in Texas closed, as though only a dream.

9/

I traveled to Iraq. At a table, Syrians in exile shared what they missed about home. The apricots. Pomegranates. Ghraowi chocolates, I suggested.

The man beside me sighed. “You win,” he said.

10/

In 2020 everyone seemed to be reading Naomi Shihab Nye’s poetry. Friends, exiled in their homes because of Covid-19, forwarded her poem “Gate A–4,” about an old Palestinian woman losing her bearings in an airport terminal when her flight is delayed. Naomi meets her, speaks to her in halting Arabic, and watches as the scene is transformed: They call the woman’s son to give him news, then Naomi’s father to speak in Arabic, then friends. Soon, the woman hands out ma’amoul cookies, dusted with sugar, to exhausted passengers. “And I looked around that gate of late and weary ones and thought, This is the world I want to live in,” Naomi writes.

When Naomi received a lifetime achievement award from the National Book Critics Circle, I wrote from Jerusalem to congratulate her. In a surreal twist, the award was presented to her by Michael Schaub, my childhood best friend, who had grown up to become a book critic.

In her reply she mentioned, almost as an afterthought, that she had just lent my book about Syria to a beloved student of hers in Texas. “She’s from Damascus,” she wrote. “Her name is Nour Al Ghraowi. Her father owns a chocolate factory.”

11/

Nour Al Ghraowi grew up in Damascus, near the base of Mount Qasioun. Beneath her house stood a chocolate factory, where her father, Bashar Ghraowi, fashioned some of the finest chocolate in the Middle East. She awakened in the morning to the smell of chocolate wafting through the windows. When she descended to the factory, she saw her father and his assistants crafting chocolate by hand: mixing butter and milk and sugar and cocoa, pouring chocolate into molds, placing each pistachio. Her grandfather, Tayseer Ghraowi, had been one of the first Syrians to bring chocolate to the country. Even today, her father kept the recipes a secret.

“I used to tell him: You need to tell me the secrets,” Nour told me when I interviewed her. “I don’t want to work in chocolate. But still, I want the secrets.”

For Nour, the factory became a school for mastering the art of the particular. Her father molded chocolates into pyramids or flat disks or flowers. Each was wrapped individually in special paper: “My dad loves colors,” Nour explains. “You’ll find orange, purple, yellow, silver, gold. The stickers could be flowers, triangles, squares. They all had my father’s name on them.”

Nour Al Ghraowi with her father, 2016

He worked in the factory in the mornings, pausing with the family for lunch. In the afternoons, Nour often accompanied him to the chocolate store in the center of the city. Customers came in, asking for chocolate-dipped cherries, apricots, and dates; chocolate-covered coffee beans; or raha, a sweet filled with pistachios and rolled in rose petals.

Nour watched. All of this became part of her. In the meantime, she taught herself to speak English, and scribbled poems in notebooks. She began to study literature at Damascus University.

Now she wonders if those days with her father found their way into her poems.

“A five-line poem can tell an entire story,” she explains. But only if you pay attention to every line break. Every word. Every sound.

12/

In 2011, war broke out in Syria. Nour applied for a visa to the United States. She was denied three times. Her family traveled to Egypt. She begged her father to return to Damascus so she could finish her studies.

So she and her father did. In her poem, “Melting Candles,” Nour describes studying by candlelight, racing against the melting wax, trying to finish her books. Bombs exploding outside.

She applied for a visa one last time. It worked. She arrived in Austin, Texas, on December 31, 2013.

None of her studies transferred. She started over from scratch, enrolling at the local community college. Her parents and brother arrived in Texas three years later, with a business visa to open a chocolate shop in nearby Corpus Christi. They purchased the machines. They began to make chocolates. Newspapers ran stories about a famous Syrian chocolate family, starting over in Texas. But her parents couldn’t speak English. When Nour had to translate for her father, she saw how hard that was for him to bear.

Before long, her parents and brother returned to Damascus. They would continue making chocolates there, despite the war.

Nour remained in the United States, transferring to the University of Texas at Austin, where she picked up a minor in creative writing. She didn’t see herself as a refugee. She didn’t see herself as an immigrant either. When she introduced herself, she said: “I’m from Syria.”

She fell in love with writing poems. “I felt that I had that power,” she tells me, “that power of a poem that can tell a lot. Especially that I had a lot to tell.”

As she prepared to graduate, a professor told her about a Palestinian-American poet named Naomi Shihab Nye, who taught in the MFA program at Texas State University.

He suggested that she go to meet her. As if to say: With her, you might feel at home.

Nour began to read Naomi Shihab Nye’s poems. She saw that she sometimes even used Arabic in her verses. She wrote about familiar olive trees.

Nour made the long drive to San Marcos. On the first day of class, she turned to Naomi Shihab Nye and said to her: “You’re the reason I’m here.”

Now, I settle in my room in Jerusalem and open Nour Al Ghraowi’s not-yet-published book of poems. I’m drawn in, again, to the Damascus streets I haven’t walked in fifteen years. Jasmine and war, a life lived between languages, the Barada River. Among the fragments: her father, fashioning chocolate. Her father, kissing her goodnight. Her father, buying candles so that she might study against the dark.

13/

We remember each other into being. We find one another across the distance.

At the end of Naomi Shihab Nye’s poem, “My Father and the Fig Tree,” Aziz Shihab finally discovers his fig tree in Texas. Or perhaps it finds him. Later, he plants a branch in Naomi’s backyard, so that she will have one too.

Today, she sits beside it nearly every day, talking to him across the void.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Ed Wolfe

Bella!