The history of committed Christian community is a story of roads. The first followers of Jesus called themselves “the Way,” a name that echoes Jewish halakha, the “way of life” enshrined in the Torah, as well as the disciples’ belief that Jesus was “the way” to God the Father.

The earliest community that formed in Jerusalem after Jesus’ execution was composed of the original disciples and pilgrims who had traveled to Jerusalem to celebrate the holy days. United by the conviction that Jesus’ resurrection was a sign of covenant renewal and the new creation, these Jews marched through the Red Sea of baptism into a radically new way of life, one in which all possessions were held in common, there were no needy persons, and all members were “of one heart and mind.” The spirit of ancient Israel engulfed the Holy City, and for a brief period of time the utopian community of the Jubilee was reconstituted.

Eventually, war drove all the Christians and Jews from the land. Still, the traces of that original movement were so impressed in their memory that the disciples who fled Jerusalem continued to establish countercultural communities of economic sharing, scripture study, participatory worship, and service to the poor.

These first Christians wended the path pioneered by Jesus. They were not the only people to live intentionally; in the early centuries of the Common Era there were other fraternal associations of mutual aid, organized by profession, religious devotion, or simply voluntary adherence. Christian communities differed from them, as Tertullian observed in the third century, in their charity to the underserved (Apology 39.5–6). Groups of Christians organized themselves into economic communities called parishes, a word derived from the Greek paroikia, which meant “neighbor” but also “sojourner” or “pilgrim.” So, just as “parish” is similar to “pariah” in English, the name would have reminded Christians they were outcasts and exiles in a foreign land.

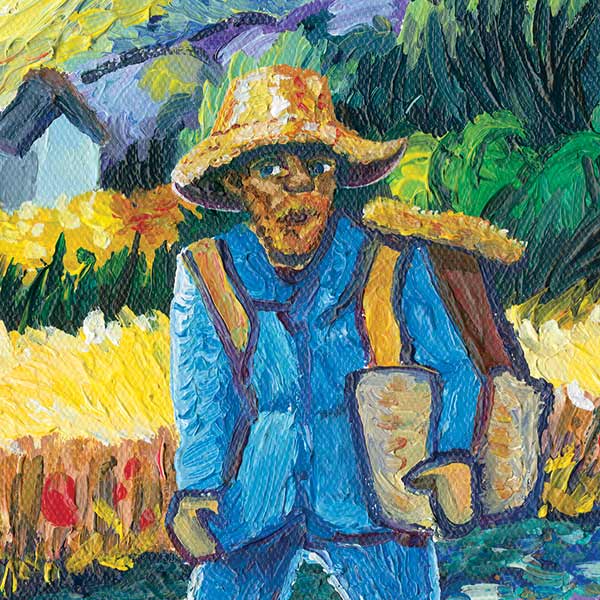

Palestinian roads were treacherous, consisting of packed earthen pathways, usually narrow and winding around the many mountains in the region. Persecution forced whole families of Christians to follow these dusty trails to new cities, where they formed tightly knit communities of a few dozen people. In times of difficulty, Christians relied on one another for basic needs. For instance, if Christians were imprisoned, they counted on the community to bring them food and care for them. Such pressures bound the parish together into a family unit, sometimes called “the household of faith.”

The development of Roman highways – between eight and thirty feet wide; built in courses of gravel, sand, and pavement; engineered to efficiently drain water away – not only made life easier but also aided the spread of Christianity throughout the empire. As external pressures relaxed, Christians’ dependence on one another likewise waned. By the end of the third century, the parish had morphed from a countercultural community into an administrative jurisdiction of the institutional church. This shift occurred at different rates in different regions, but by the end of the fourth century Christianity was the official religion of the Roman Empire and firmly established in major urban areas. From this point until the modern period, Christians in Europe would live in tension between a supposedly “Christian” society and the communal ideal of the early church.