In 1826, in Connecticut, a farmer named Josiah Holbrook started a school for “the general diffusion of knowledge and … raising the moral and intellectual taste” of Americans. In those days, the opportunities for higher education were limited to those venerable old universities that had long served the upper crust. Holbrook’s vision was to make learning – practical, liberal, and humane – available to working people of all kinds. He named his school the Lyceum, after the garden where Aristotle once taught his students philosophy.

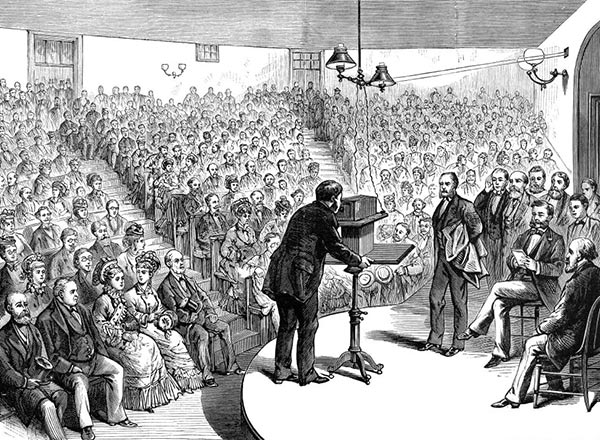

The idea spread like wildfire. Within a few decades, there were thousands of lyceums across the country, representing a thriving intellectual life in large cities and small country towns. Abraham Lincoln gave his first public speech at a lyceum in Springfield, Illinois. Frederick Douglass, Mark Twain, Susan B. Anthony, and all the great thinkers of the day toured the lyceum circuit, putting their ideas in dialogue with ordinary Americans. Henry David Thoreau wrote for his local lyceum in Concord. When Alexander Graham Bell debuted the telephone, it was at a lyceum. In Jefferson, Iowa, or Brookline, Massachusetts, you could find working folks listening to lectures on anthropology, philosophy, politics, and more.

And then the lyceum disappeared. Communities broke apart in the Gilded Age as families moved and shifted toward big cities. Individualism replaced the communal learning of the past and social Darwinism became the new philosophy du jour. In reaction to growing individualism and weakening community life, grassroots organizations, like the Rotary Club, Kiwanis Club, Lions, and others, were formed to knit communities back together. Protestant Americans emphasized the “social gospel,” and Catholics introduced the language of “social justice.” Lyceums, too, saw a revival in the form of the public forum movement. These and other factors contributed to historically high levels of social trust and civic participation in the middle of the twentieth century.

Alexander Graham Bell demonstrating his experimental telephone, with a connection between Salem and Boston, Massachusetts, in Lyceum Hall, Salem, 1877. Sketch by E. R. Morse. Image from Library of Congress (public domain).

But, as social scientist Robert Putnam famously documented in Bowling Alone, social cohesion, community engagement, and community trust have plummeted across a wide array of measures since that time, and these things have taken a nosedive from the 1990s to now. People report fewer conversations with neighbors, fewer friendships, less engagement in community organizations and civic life, and a growing distrust of their fellow Americans. Coincident with all this, our engagement with ideas has moved away from a public forum with neighbors and toward TV and social media, where the humanizing element of physical proximity is lost. No longer are we in the scrum of intellectual engagement with those with whom we live; instead, we are locked in our own angry echo chambers online, growing ever more extreme and unable to sympathize with those unlike us.

In this environment, the Lyceum Movement has launched an effort to bring back this forum for conversation and learning. In its time, the lyceum was a way for neighbors to form relationships around a common pursuit of learning. This is eminently good for a community. In the process of shared learning and intellectual exploration, trust and shared understanding grow, and a habit of cooperation in search of a shared good, the good of knowledge, is formed.

In the midst of a confusing turmoil of online noise, the lyceum offers a place to think about first principles and about the stories we share. We hold lectures, panels, classes, and community conversations in a relaxed social atmosphere. Human beings have always needed this, whether in the Greek agora or a Boston tavern; we need a place to pursue the fundamental human desire to know with our neighbors.

Since its beginning in 2021, the new Lyceum Movement has grown to a presence in four states and six cities, and it has generated a remarkable amount of positive energy in communities large and small. People are hungry for an alternative to the alienating experience of life online; they’re hungry for a substantive conversation with a neighbor.

We take the subjects of the liberal arts and put them in local contexts. In Des Moines, Iowa, we’ve spoken about virtue ethics by way of a discussion between commodity farmers and farmers focused on sustainability. We’ve explored questions of human solidarity through dialogue between philosophers and refugees. We’ve explored local history in places like Duluth, Minnesota, and St. Louis, Missouri. These are subjects many people think about in the quiet moments of their working lives, and they are hungry for an opportunity to develop those thoughts with the help of a scholar or expert and in conversation with their neighbors. This is often true of those who don’t suspect that this kind of intellectual talk is for them. Not everyone is an academic, nor should they be, and our events have been places where a farmer, a construction worker, a lawyer, and a schoolteacher can think deeply together.

A healthy common life requires a shared frame of reference, a shared language, and a shared sense of purpose. If we only talk as a community at times of political conflict, we are bound to talk past each other. We won’t have a shared understanding of the very words we are using, we won’t have shared stories to point to, and we won’t have relationships of trust to ground us. The liberal arts can offer something here. Studying philosophy, literature, and history in community can at least give us a common set of terms, a better understanding of our neighbor’s point of view, and a shared frame of reference so that we can fruitfully disagree.

We need to go deeper than the superficial fights that characterize public life. We need to return to first principles and meet each other there as human beings. The lyceum is working to provide a space to do this, with the goal of bringing back the lyceum halls that once served as centers of community learning and thinking for so many towns and cities. Learning in community is not a panacea for our complex problems, but it can help cultivate the soil from which productive work for the common good may grow.

This is a chapter from The Liberating Arts: Why We Need Liberal Arts Education (Plough, September 2023).