Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Family and Friends: Issue 19

-

Verena Arnold

-

Tundra Swans

-

A Debt to Education

-

What’s the Good of a School?

-

A School of One

-

On Praying for Your Children

-

The World Is Your Classroom

-

The Good Reader

-

Orchestras of Change

-

The Habit of Lack Is Hell to Break

-

Kindergarten

-

The Given Note

-

Editors’ Picks Issue 19

-

Litanies of Reclamation

-

The Children of Pyongyang

-

How Far Does Forgiveness Reach?

-

A Trio of Lenten Readers

-

Michael and Margaretha Sattler

-

The Blessed Woman of Nazareth

-

New Heaven, New War

-

Born to Us

-

My Fearless Future

-

Covering the Cover: School for Life

-

The Community of Education

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

We welcome letters to the editor. Letters and web comments may be edited for length and clarity, and may be published in any medium. Letter should be sent with the writer’s name and address to letters@plough.com.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Healing, not Band-Aids, for Combat Veterans

On Scott Beauchamp’s “Warriors on Stage,” Autumn 2018: Beauchamp’s critique of contemporary attempts at dealing with combat veterans’ spiritual and psychological injuries rightly asks how effective these really are. Programs that stay within the bounds of secular therapy, he argues, are insufficient for addressing the damage suffered by warriors. As an example, he takes the Greek dramas staged by Theater of War Project, in which American veterans play parts written by an Athenian veteran. Originally religious, the Greek plays can’t be used outside their religious context as technical fixes – even artistic technical fixes – of spiritual problems.

But productions of Sophocles’ Ajax are not the only things that fail to take seriously the spiritual reality of the wounds of war. Military ministry – which is, or at least ought to be, at the frontlines of postbellum trauma treatment – itself frequently fails to meet this need for the transcendent. At least in my experience as an Air Force chaplain, military ministry often falls into the same trap that Beauchamp identifies. It sees itself more as a sort of spiritual Band-Aid, a therapeutic measure taken for the purpose of getting the troops “spiritually fit to fight,” than as a source of genuine healing and redemption.

The problem is, of course, that the ordering principle for us chaplains is still the advance of the nation-state by violence. The human person is made an instrument for that end. Spirituality is ornamentation or tool. This framework, as Beauchamp suggests, cannot provide the transcendental vision necessary for the kind of healing required for the veteran’s reintegration into society and eventual flourishing.

Chaplains must provide a counter-narrative, an eschatology that promises, in Christ, something more than the worldwide triumph of the secular nation-state. Only this can heal: this invitation into a form of life beyond the violence of the city of man. Chaplains and other ministers must, in short, be reminders of the holy. We must tell soldiers that they are not militarized instruments of the nation-state: they are children of God. Fair warning to my fellow chaplains: this might not (and probably won’t) directly advance the mission, and might even prove disruptive or require self-sacrifice. Which is to say, it might require we be Christian.

In his eloquent critique of the Theater of War project, Scott Beauchamp examines it against the backdrop of moral injury. Weaving together anecdotal accounts, clinical research, and theological reflection, Beauchamp analyzes the strengths and weaknesses of this attempt to resurrect an ancient practice for the purpose of healing returning combat veterans.

Beauchamp posits that while the arts offer potential for healing, no true healing occurs apart from salvation. This is of course true, but his conclusion raises more questions than it answers. What could the church offer as a practice which would be an alternative both to Theater of War as it exists now, and to the religious performances of Athens?

Noticeably absent from Beauchamp’s discussion of rituals of healing for returning warriors was the Christian practice of pilgrimage. When, several years ago, I was serving soldiers diagnosed with PTSD, I became intrigued with this practice and made it the focus of my doctoral dissertation. Since then, others have adopted and used my research. The responses of combat veterans who participated in pilgrimages are overwhelmingly positive both in terms of soul healing and in restoring these men’s and women’s relationships with God.

Though pilgrimage offers many of the same clinical benefits as theater, it goes beyond it, creating space for combat veterans to bring their pain, guilt, shame, and grief to Christ through daily acts of devotion, prayer, and communal worship. While no perfect solution exists, perhaps this ancient redemptive practice of the church is one to which veterans suffering from the trauma of war might return.

Reckoning with Repentance

On Emily Hallock’s “A Man of Honor,” Autumn 2018: I will not be renewing my subscription to Plough. Emily Hallock’s article in your last issue is a shameful and potentially harmful viewpoint. I pray no LGBTQ persons read this and feel their inherent self-worth and goodness demeaned.

The only glimmer of hope in this article is a call to be more welcoming to LGBTQ persons – but that is quickly soiled by referring to her father giving in to temptation, or a lesbian woman who was able to “renounce her … lifestyle.” In a world that already subjects LGBTQ to significant abuse, the potential for further harm through a viewpoint like this is monumental. The LGBTQ suicide rate is significantly higher than that of straight people. And articles like Hallock’s contribute to this.

Emily Hallock responds: I’ve received numerous responses since sharing my father’s story, among them several like Brian Chenowith’s. It goes without saying that I share Chenowith’s concern for vulnerable people. But can it really be true to claim, as he does, that the mere act of writing a true story such as my father’s is “shameful” and “harmful”? As is clear from other responses I’ve received to the article, my father’s experience, and ours as a family, is hardly unique.

There’s an essential element of my father’s story that Chenowith fails to reckon with. What made my beloved Dad feel remorse for his gay relationship, and then for the HIV infection that eventually took his life, was not society’s judgment. It was the judgment of his own conscience: an inner sense of conviction for sin. When he repented, he was given a peace and a joy that he recognized as the fruit of being freed from an evil through God’s forgiveness. His peace and joy were a blessing for our whole family, something I will always remember now that he is gone.

Yes, we need a lot more compassion for one another; Christians in particular must do far better here, as I write in my article. Such compassion cannot mean silencing those stories, like my Dad’s, that may seem unsettling or controversial. Surely, true compassion includes respect for the dignity and inviolability of each person’s conscience.

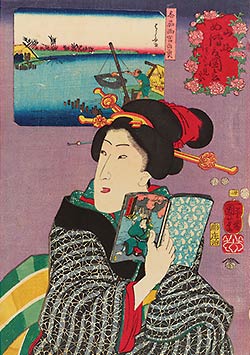

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Landscape and Beauties – Feeling Like Reading the Next Volume Image from Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

Seeing Everyday Beauty

On Roger Scruton’s “The Beauty of Belonging,” Autumn 2018: Reading Roger Scruton on matters of beauty is a pleasure, if something of a guilty one. At times he paints with a broad rhetorical brush, and I’m never quite sure if I’ve been carried away in metaphysical safety, or not. I’m a bit of a sucker for the praise of beauty, and so I remain susceptible. One strives, however, to be a reformed aesthete, with a Plato on the shoulder to remind one that the Beautiful and the Good don’t always coincide.

I admire Scruton’s attempt to join together what Hegel declared divorced forevermore, that is, art and religion. But it’s easier to see the connection he makes between beauty and the sacred than to hear what he thinks beauty has to say in the tumble of the everyday. That’s where his argument falters for me. I worry that his beauty seems at once too grand and not self-respecting enough: I’m not willing to concede that all buildings are shrines somehow, even if I agree that buildings do better with a shrine in them. He wants it clear that beauty accommodates itself to the everyday; while the everyday, lacking beauty wholesale, requires beauty’s abbreviation as awkward window dressing.

Heraclitus had an uphill battle when he refused to budge from the kitchen, inviting his foreign guests to come in, “for here there are gods also.” But the missing piece is here somewhere: van Cleve’s Mary is beautiful in her beautiful bedroom, but I fear for her ability to dust that chandelier, particularly while pregnant. In my house-icon of the Annunciation, Mary turns to the angel with household spinning still in hand. There’s something in the sacred plainness of her ordinary tasks arrested that I can believe in, and trust that here at least, beauty will carry one safely to the Good.

Is Community Possible without Faith?

On Eberhard Arnold’s “Why We Live in Community: A Manifesto,” Autumn 2018: The call of the gospel necessarily impels us toward a different mode of living; this mode must be oriented toward the community of God’s people. This is the heart of Arnold’s manifesto, and to it I assent completely.

Yet I worry that Arnold understates the power of common grace. It’s a criticism that has been leveled at my own tradition: Calvinists are sometimes accused of believing that man is utterly depraved rather than totally depraved. The distinction is significant: The former says that we are completely given over to evil; the latter that there is no part of us untouched by sin. When we embrace the latter doctrine, we can add that because of God’s common grace – he freely gives good gifts to all people everywhere – we can recognize in nearly any human community some traces of leftover goodness not totally erased by the Fall.

Evangelical theologian Scot McKnight refers to this vestige as a cracked icon – something beautiful that, though marred, can still reveal true traces of its former grandeur. The Reformed missionary Francis Schaeffer spoke of “glorious ruins.”

I wonder if Arnold does not overstate the degree of damage to these icons and erosion to the ruins. He writes, “Here it becomes abundantly clear that the realization of true community, the actual building up of a communal life, is impossible without faith in a higher Power.”

Surely this exaggerates the degree to which the natural order has fallen. Certainly, faith in God is necessary to realize what my church’s confession calls “the chief end of man:” to glorify God and enjoy him forever. But even in an unregenerate state, human beings can and regularly do form communities that reflect some truth about the world and about humanity, and do so in a significant enough way that I am loathe to call them “false” communities, which seems to be implied by Arnold’s manifesto.

We have all known happy marriages that, even without knowledge of God, show forth the beauty of married life. We have seen neighborhoods and small towns filled with people who do not know Jesus and yet model genuine care and love for one another. These communities might be incomplete, but to call them “false” seems to minimize the traces of common grace still displayed in their members.

What this manifesto can do, however, is to remind us that these communities are incomplete: that each is called to be transformed by the Holy Spirit through the faith of the community members, and thus to become completely itself, and a part of the complete community that is the kingdom of God.

Reading Icons

On Navid Kermani’s “It Could Be Anyone,” Autumn 2018: Kermani’s description of Caravaggio’s The Calling of Saint Matthew is perceptive and impressive, rooted in the painting’s form itself. In particular, I admire his analysis of how the figures interact along with other elements to create this feeling of both immediacy and confusion – an effect that Caravaggio evokes in many of his paintings. Kermani seems to have a natural understanding of how Caravaggio seamlessly integrates these formal qualities with the actual content of the work: the strange, abrupt, and confusing story of Saint Matthew’s call.

It’s this same careful attention to the aesthetics of the work itself that I wish he had brought to the first piece he considers: the early icon of Mary in the convent of Santa Maria del Rosario. Icon painters are known as icon writers, and as Kermani read Caravaggio’s painting, so I would love to hear his reading of the image of Mary.

Plough Mailbag

What a breath of fresh air Plough brings to me! When the magazine arrives, I prepare a cup of tea, then carefully remove the outer protective packaging and just hold the magazine: sensing the contents, feeling its weight and the texture of the cover. Then I peruse the contents, looking at the artwork and reading the poetry. At the next sitting I delve into the essays, reading one or two depending on my schedule. By then several days have passed and I sigh, finishing my ritual – letting the issue sit on my desk for a while longer before placing the magazine among other issues of Plough Quarterly that I’ve purchased over the years. The articles and artwork stay with me for weeks. Plough has become an essential part of my spiritual and personal growth.

Vincent van Gogh, Old Man Reading Image from WikiArt (public domain)

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.