Subtotal: $

Checkout

The Backbone of a Country

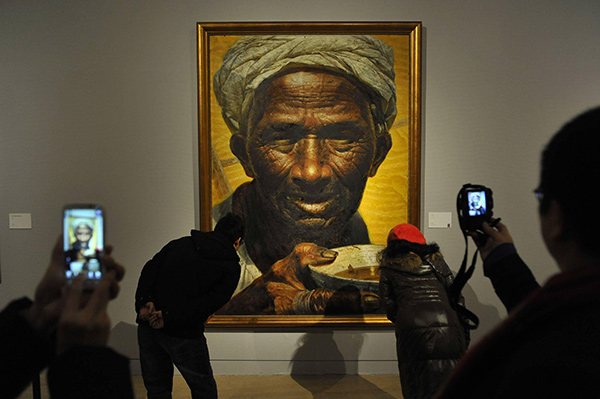

Luo Zhongli’s 1980 painting Father portrayed an aging farmer in a format usually reserved for deifying China’s political leaders.

By Evelyn Mow

March 2, 2025

In a painting that intimately contemplates a resident of a remote mountain region of China, the artist Luo Zhongli shows us something universal – the image of God – that indestructible essence that God breathed into the first human beings. Luo may not be a practicing Christian, but in this painting, he expresses something of the God-given dignity of all humankind.

One year after Luo Zhongli was born in 1948 in Chongqing, Mao Zedong officially established the People’s Republic of China. Mao understood perfectly the power of the arts to help or hinder his party: “Literature and art [must] become a component part of the whole revolutionary machinery,” he had mandated in his Yan’an talks of 1942, “so they can act as a powerful weapon in uniting and educating the people while attacking and annihilating the enemy.” Traditional Chinese ink painting was sidelined along with other cultural aspects labeled as elitist, and contact with cultures outside of China was banned. Religion was forbidden as well, to be replaced by the Communist State itself. The new art of the “revolutionary machinery,” known as socialist realism, centered state leaders almost as icons of veneration. In fact, as historian Dong Xioling reported, Mao had himself portrayed in the arts as “the image of a supernatural god. Mao was worshipped as an idol.”

By the time Luo entered his teens, no role legally existed for artists and writers apart from the propagation of state-approved work, and anyone unwilling to comply risked being denounced, imprisoned, and worse. Luo’s parents had encouraged his early interest in art and enrolled him in a high school attached to the prestigious Sichuan Fine Arts Institute (SFAI) in Chongqing, the only university of its kind in Southwestern China. But a nation-wide campaign prevented him from continuing at the Institute after high school graduation. The campaign forced the closure of all the universities in China and sent millions of college-age students to underdeveloped areas of the country, to be “re-educated” by living alongside the farmers and factory workers. Luo Zhongli was among them, traveling to the Daba Mountain region, where he remained for the next ten years.

Photograph by Imago / Alamy Stock Photo.

In a 2012 interview, Luo recalled the nighttime arrival at his destination, where rural residents met the city kids to guide them to their new quarters. “The torches and oil lamps they were holding looked like sparks scattered across the Daba Mountains’ terraced fields,” Luo recalled. “It was a silent, slow-motion fairy tale.” The fairy tale world must have vanished quickly for the urban art student. As Luo would later memorialize on canvas over and over, the Daba Mountain region of the 1970s showed no sign of the economic progress Mao’s government had promised – the residents of Luo’s new home used oil lamps and torches because they had no other option. The farmers often traveled on foot, without the benefit of paved roads or bridges, and their dwellings lacked plumbing and electricity. Stone hand mills, which would come to feature often in Luo’s paintings, rested outside each home, used for grinding the grain cultivated on the nearby terraces. The fertilizer for the fields came from the latrines.

More fortunate than many of his peers, Luo found steady work as a repairman in a steel factory, and a stable home with the family of Deng Kaixuan, for whom he developed a deep affection and respect. He would stay in touch with Deng’s extended family for over fifty years.

During his stay, Luo had an encounter that would affect his entire career. One New Year’s Eve, Luo was taken aback to see an aging farmer working overtime while other families gathered to celebrate the holiday. The man was posted as a guard outside a public toilet, tasked with preventing the theft of the coveted fertilizer. “That day, a middle-aged farmer was guarding the manure pit near my home. In the morning I noticed he was shivering in the snow…. When night fell, I saw him still standing there under the dim lamplight…. At that moment, my heart surged with a powerful feeling.” Luo was touched by the man’s humility and his willingness to endure for the benefit of his family, and saw in him a symbol of all the farmers in China, those who “collect manure and turn it into food to feed the country, to nurture this nation.” He became convinced that the farmers were “the main body and backbone of a country.”

Luo’s painting suggested that an old farmer could be as important to his country as Mao himself.

After Mao’s death in 1976, universities began to re-open, and Luo was finally able to enter the SFAI in 1977, at the age of twenty-nine. Luo described his years in the SFAI as “a period of social transformation.” Youth who had grown up in the People’s Republic of China without a faith or traditional culture other than that created by the communist government began to question the demands of the regime. “The old ideology had been proven wrong. But a new one hadn’t yet formed,” Luo recalled in an interview. “We were excited yet blind and full of doubt about China’s future development.” Luo and other classmates rejected the approved socialist-realist art styles and instead created their own clandestine exhibit with artwork that began to “explore the wounds of the Cultural Revolution.” Eventually, they received support from sympathetic superiors to show their work, and their efforts grew into an artistic movement known as “Scar Art,” which generated several ground-breaking works in the history of Chinese modern art. Possibly the most well-known of these, at least to the Chinese people, is the oil painting Father created by Luo Zhongli in 1980, based partly on his memory of the latrine guard in the Daba Mountains.

After reading a detailed description of the photorealistic work of Chuck Close, known for his enormous portrait paintings that exposed every blemish and idiosyncrasy of his subjects, Luo was inspired to create a similarly large, photorealistic portrait over seven feet tall. At the time, such a large format was reserved for portraits of Mao or other state leaders; canvases that size weren’t even available for student work, so he used two, hand-stitched together by a teacher. In direct defiance of socialist realism, this painting did not celebrate the accomplishments of the government or present a deified image of a political figure. The aging farmer’s weathered, finely wrinkled face and his calloused hands speak of hardship and strenuous labor; details such as the bandaged fingers, the cracked, dirty bowl of tea, and the glimpse of a wooden hand tool in the background give no hint of prosperity or modernization. The scale of the work gives these humble, even painful details an air of authority and command. Luo titled the painting Father.

Luo entered the painting in the National Youth Art Competition in Beijing, a potentially dangerous move despite the fact that Mao had died two years previously. At the insistence of his superiors, Luo added a ballpoint pen tucked behind the farmer’s ear to indicate that the farmer was an educated revolutionary aligned with communist ideals, thus raising the chances that the painting would be accepted into the competition. Ultimately, Father was accepted, and won the gold medal, earning Luo instant fame. He also received a cash prize of 450 yuan (about $66). Decades later he described to an interviewer how his classmates teased him: “Luo had some damn good luck. Now he has to treat the class to a bang-up meal!” The class got their treat.

The creation of Father marked a turning point for China. As art historian Dong Xiaoling points out, “Today, the people viewing this large-size portrait may not be able to imagine what the people felt [in 1980] when they stood in front of … Father for the first time. Those people experienced a visual shock and an impact to their values…. At that time, people were used to seeing the huge portraits of Mao Zedong or Marx only.” Luo’s painting suggested that an old farmer could be as important to his country as Mao himself. Speaking of the work, Luo commented, “My core was the concept shift – the time of gods has passed, and here comes the time of man, upon whom our livelihoods really depend.”

Which gods is Luo referring to? One can assume his words are calling out state leaders posing as a godlike figures with unlimited power, not the traditional deities of the religions those leaders had rejected. A close study of Father powerfully communicates the man of the earth, one who has borne others’ burdens, who has been bowed down to the point of exhaustion on behalf of those he loves. The light resting on his face and on the bowl of tea seem to immortalize him, celebrating his humanity as something that perhaps lasts beyond death. However Luo intended this beautiful detail on the face of a forgotten man, that lighted countenance testifies to the image of God in all who have worked, suffered, and sacrificed.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.