Subtotal: $

Checkout

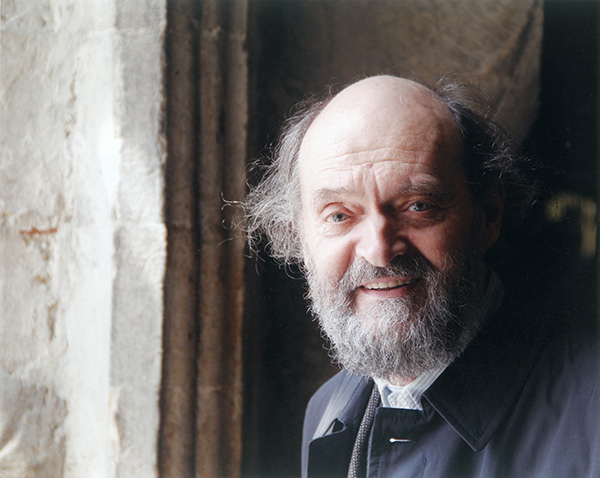

Harmonizing Silence

Estonian composer Arvo Pärt understands the space between sounds.

By Joel Clarkson

October 23, 2024

The Plough Music Series is a regular selection of music intended to lift the heart to God. It is not a playlist of background music: each installment focuses on a single piece worth pausing to enjoy.

Silence is golden. The familiar adage is simple enough, although its sentiment is rarely attained by most of us in this age of relentless noise. Modern life moves at such a breathless pace and our lives are so entirely occupied by action that the idea of silence exists in our minds as a sort of longed-after restfulness, a state of peace just beyond our reach. And yet, when we arrive at the threshold of such quiet, the possibility of emptiness makes us agitated and restless. We find ourselves immediately turning back to the patterns of meaning and activity that we only just left behind, unable to face the openness before us.

For the Estonian and Eastern Orthodox composer Arvo Pärt, this view of silence is upside down. It is only in stillness that the essential meaning of our lives can emerge. Pärt paints his music in sparing brushstrokes on the canvas of silence, employing his own unique style. He calls it tintinnabuli, from the Latin tintinnabulum, meaning bell. Here, only two musical lines exist at any given time, one moving in gradual stepwise motion, and another moving in and around it in some form of triadic harmony, whether in chordal or arpeggiated form.

Photograph by Eric Marinitsch. Courtesy of the Arvo Pärt Centre.

The music is spare, with little, if any, real development. It seems to exist in a state of singularity, with each individual voice emerging from, circling around, and returning to the whole. Paul Hillier, a longtime biographer of Pärt, suggests that his music “might be described as a single moment spread out in time.” Like the strike of a bell, which includes not only the initial sharpness of the peal but also its lingering reverberation that fades gradually into nothing again, there is indeed a relationship in Pärt’s tintinnabulation between the particular and the universal, between sound and silence.

One of Pärt’s earliest tintinnabuli pieces, “Für Alina,” exquisitely demonstrates his bell-like sound and the way it uses sustained intervals of openness to gather all the tensions and harmonies of a preceding phrase into a hushed unity. Listen to Jürgen Kruse’s performance of it here:

Why is this restraint so essential? Pärt himself gestures toward an answer: “I believe that this concept should not only be conveyed in the text, but in every note of the music as well, in every thought, in every tone. The roots of our skill lie in this thought: ‘In the beginning was the Word.’”footnote

Music need not – must not – be overly expressive, for the mystery of the Incarnation is already active in the whole of creation. All things, whether music, nature, or words themselves, emerge from Christ the Logos, the eternal Word. Tintinnabuli is not simply a musical device that represents ideas about Christ or creation. Rather, it seeks to awaken the eyes of the heart to the divine light shining through all things. For Pärt, silence is, in one sense, actually golden: suffused with the radiance of Christ’s life-giving presence, arising to the ear and the heart only when one allows the noise of the everyday to die away into stillness.

Because tintinnabuli is established upon the open field of quietude, it speaks in an especially potent way to those who have been thrust into the dreaded silence of human suffering. In response to such silences – spaces that can feel so vacant of hope and meaning – Pärt’s hushed music doesn’t seek to fill the void or distract from it, but rather to gently hallow it, transfiguring a location of pain into a space of encounter with the love of the God who, as Psalm 34:18 says, is “close to the brokenhearted.” This is reinforced by numerous reports of hospice patients who request Pärt’s music as they approach the end of their lives. Two such accounts describe suffering individuals asking for Pärt’s “angel music,” identified in one account as “Silentium,” the second movement of Pärt’s double concerto for solo violins, prepared piano, and chamber orchestra, Tabula Rasa. Gidon Kremer performs solo violin and conducts the Kremerata Baltica in a performance of it here:

The power of Pärt’s tintinnabuli music and its capacity to accompany instances of suffering has been taken up in popular culture as well. “Silentium” recently made an appearance in Terrence Malick’s 2020 film A Hidden Life, depicting the German conscientious objector Franz Jägerstätter, who was executed for refusing to fight for Nazi Germany. Malick used the piece in a pivotal scene to act as the unspoken narrative of Jägerstätter’s unflagging interior devotion to his faith, despite the outer world falling apart around him.

In a very different work of art, on the day after the twelfth anniversary of the horrific events of September 11, 2001, the New York City Ballet released a short film entitled New Beginnings. The sequence is a movement from Christopher Wheeldon’s ballet After the Rain, and was performed at dawn on the fifty-seventh floor of 4 World Trade Center in New York City. The hushed and simple scene is accompanied by Pärt’s piece for piano and cello, Spiegel im Spiegel, and imagines the hope that bursts bright after the despair of a long, dark night. Here it is performed by Michael Harrison and Maya Beiser:

In this music, we grasp a notion of what Pärt expresses so profoundly: that in all our silences, whether in the tranquility of stillness or the emptiness of suffering, there awaits the Incarnate One, the Suffering Servant, whose mighty word sustains all of creation and whose self-giving love breaks open our solitude and fills it with himself.

Footnotes

- Enzo Restagno, Leopold Brauneiss, Saale Kareda, Arvo Pärt, Arvo Pärt in Conversation, trans. Robert Crow (Dalkey Archive Press, 2012), 66.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.