Subtotal: $

Checkout-

The Good Samaritan

-

Readers Respond: Issue 7

-

Family and Friends: Celebrating Marriage

-

The Gospel at the Margins

-

Our Daily Bread

-

Forgiving Kim Jong-Il

-

Poem: Twilight

-

Snapshots from Lesbos

-

Family and Friends Issue 7

-

The Courage to Forgive

-

Insights on Mercy

-

Forgiving the Unforgivable?

-

Forgiving Dr. Mengele

-

The God Who Descends

-

The Weapons of Grace

-

Restorative Justice

-

Bard of God’s Circus

-

Editors’ Picks Issue 7

-

Rediscovering Wonder

-

Educating for the Kingdom

-

Being Obedient to Christ

-

Learning from Sister Charis

-

Coward, Take My Coward’s Hand

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

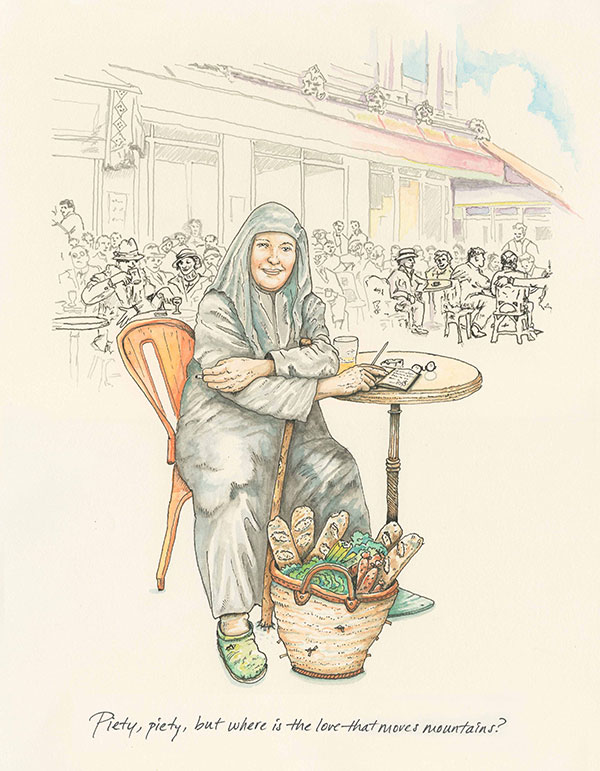

Paris, ca. 1932: “I was walking along the Boulevard Montparnasse and I saw: in front of a café, on the pavement, there was a table, on the table was a glass of beer and behind the glass was sitting a Russian nun in full monastic robes. I looked at her and decided that I would never go near that woman.” So Metropolitan Anthony remembered his first encounter with Mother Maria Skobtsova.

Mother Maria was born in 1891 in Riga and christened Elizaveta Pilenko. Her father died while she was still a teenager; this led her to become an atheist. After moving with her mother to St. Petersburg, Russia, she drifted into socialist circles, and at age eighteen married Dmitri Kuzmin-Karaviev, an Old Bolshevik activist. They separated after only three years, shortly before the birth of their first child.

Though soon disillusioned by the endless theorizing of many would-be radicals, Elizaveta, now a recognized poet, never lost her passion for social justice. Gradually, this passion led her back to Jesus, though she still espoused atheism. In Jesus, she saw one who was oppressed and yet who died heroically for others.

Jason Landsel, Forerunners: Mother Maria of Paris

In 1917, the Russian Revolution began with fierce fighting between the communist Red Army and the reactionary White Army. Elizaveta, who had served as deputy mayor in a Red town, was captured by the White Army and charged as a revolutionary. Thanks to a compassionate judge, Daniel Skobtsov, she was spared the death penalty. She visited him after the trial to express her thanks; a few days later they married. Fleeing Russia to escape the Bolsheviks, the couple eventually moved to Paris.

In 1926, Elizaveta’s young daughter Anastasia died. Keeping watch over her, Elizaveta felt that at last she glimpsed the depths of eternity and the meaning of repentance. She wrote:

Now I want an authentic and purified road. Not out of faith in life, but in order to justify, understand, and accept death.… No amount of thought will ever result in any greater formulation than the three words, “Love one another,” so long as it is love to the end and without exceptions. And then the whole of life is illumined, which is otherwise an abomination and a burden.

That year, she separated from her second husband, devoting herself to social work. She took vows as an Orthodox nun six years later, taking the name Maria. Soon the spiritual self-concern of Christians was infuriating her just as much as leftist theorizing had. “Piety, piety,” she wrote in her diary, “but where is the love that moves mountains?”

Prompted by that love, she pioneered what she called “monasticism in the world,” founding a house of hospitality for homeless women. As the community grew, Mother Maria often reminded her sisters that their calling was simply to “give from the heart,” since “each person is the very icon of God incarnate in the world.”

After Nazi forces occupied Paris in 1940, Mother Maria joined an underground circle providing false papers for Jewish Parisians. In 1943, she was arrested and sent to the Ravensbrück concentration camp. According to fellow inmates, she would regularly gather the other women for encouragement, often sharing her food rations at the cost of her own health. On Good Friday 1945, she, together with other sick prisoners, was selected for the gas chambers. She died on Holy Saturday, as the guns of the approaching Red Army boomed in the distance.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

George Marsh

"Piety, piety, but where is the love that moves mountains?" This gifted expression is "good news."

Marilyn Gardner

Love seeing an article about this little known, but amazing woman. Anberin Pasha, a film maker, is working on a film about her life. She is weaving the lives of four women today through the narrative of the life of Mother Maria, and her commitment to unconditional love. Thank you for writing about her.