Subtotal: $

Checkout-

The Book of the Creatures

-

Letters from Readers

-

Vulnerable Mission in Action

-

Community-Supported Agriculture in Austria’s Weinland

-

My Forest Education

-

Regenerative Agriculture

-

Into the Sussex Weald

-

The Abyss of Beauty

-

Let the Body Testify

-

Ernest Becker and Our Fear of Death

-

Singing God’s Glory with Keith Green

-

More Fish Than Sauce

-

Return to Idaho

-

The Glory of the Creatures

-

Poem: “The Path”

-

Poem: “The Berkshires”

-

The Secret Life of Birds

-

Why Children Need Nature

-

Made in the Image of God

-

The Lords of Nature

-

Editors’ Picks: The Opening of the American Mind

-

Editors’ Picks: Klara and the Sun

-

Writing in the Sand

-

City of Bees

-

Sister Dorothy Stang

-

Midwestern Logistical Small Talk

-

Covering the Cover: Creatures

-

Love in the Marketplace

-

The Elemental Strangeness of Foxes

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

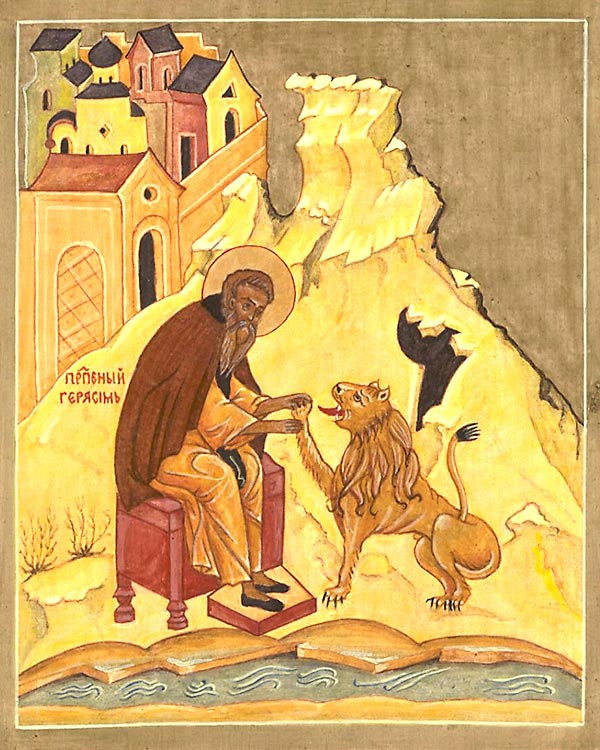

Among saints remembered for their peaceful relations with dangerous animals not the least is Gerasimos, shown in icons healing a lion. The story behind the image comes down to us from John Moschos, a monk of Saint Theodosius Monastery near Bethlehem and author of The Spiritual Meadow, a book written in the course of journeys he made in the late sixth and early seventh centuries. It’s a collection of stories of monastic saints, mainly desert dwellers, and also an early example of travel writing. Recently, it inspired William Dalrymple to write From the Holy Mountain, in which the author sets out from Mount Athos to visit places – in Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, and Egypt – that Moschos described.

In the fifth century, Gerasimos was abbot of a community of seventy monks who lived in the desert east of Jericho, a mile from the River Jordan. They slept on reed mats, had cells without doors, and – apart from common prayer – normally observed silence. Their diet consisted chiefly of water, dates, and bread. Gerasimos, in ongoing repentance for having been influenced by the teachings of a heretic in his youth, is said to have eaten even less than the norm.

One day, while walking along the Jordan, Gerasimos came upon a lion roaring in agony because of a large splinter embedded in its paw. Overcome with compassion for the suffering beast, Gerasimos removed the splinter, drained and cleaned the wound, then bound it up, expecting the lion would return to its cave. Instead the creature meekly followed him back to the monastery and became the abbot’s devoted pet. The whole community was amazed at the lion’s apparent conversion to a peaceful life – he now lived on bread and vegetables – and his devotion to the abbot.

Emelia Clerkx, Saint Gerasimos Used by permission

The lion was given a special task: guarding the community’s donkey, which was pastured along the Jordan. But one day, the donkey strayed and was stolen by a passing trader while the lion napped. After searching without success, the lion returned to the monastery, its head hanging low. The brothers concluded the lion had been overcome by its instinctual appetite for meat. As punishment, it was given the donkey’s job: to carry water each day from the river to the monastery in four earthen jars.

Months later, it happened that the trader was coming along the Jordan with the stolen donkey and three camels. The lion recognized the donkey and roared so loudly that the trader ran away. Taking its lead rope in his jaws, the lion led the donkey back to the monastery with the camels following behind. The monks realized, to their shame, that they had misjudged the lion. The same day Gerasimos gave the lion a name: Jordanes, for the river.

For five more years, until the abbot’s death, Jordanes was part of the monastic community. When the elder fell asleep in the Lord, Jordanes lay down on the grave, roaring with grief and beating his head against the ground. Finally Jordanes rolled over and died on the last resting place of Gerasimos.

The narrative touches the reader intimately, inspiring the hope that the wild beast that still roars within us may yet be converted – while the story’s second half suggests that, for those falsely accused of having returned to unconverted life, vindication may be possible.

The traditional icon of Saint Gerasimos focuses on an event of physical contact between monk and lion – an Eden-like moment. By the river of Christ’s baptism, the ancient harmony we associate with Adam and Eve is renewed. The enmity between humanity and creation is over, at least in the small island of peace that Christ brings into being through grace. The icon is an image of peace – one-time adversaries no longer threaten each other’s lives.

But could the story of Gerasimos and Jordanes be true?

Certainly the abbot Gerasimos is real. Many texts refer to him. Soon after his death, he was recognized as a saint. The monastery he founded lasted for centuries, a center of spiritual life and a place of pilgrimage. He was one of the great elders of the Desert. But what about Jordanes? Might the lion be a graphic metaphor for the saint’s ability to convert lion-like people who came to him?

Unlikely stories about saints are not rare. Some are so remarkable – for example Saint Nicholas bringing back to life three murdered children who had been hacked to pieces and boiled in a stew pot – that the resurrection of Christ seems a minor miracle in contrast. Yet even the most far-fetched legend usually has a basis in the character of the saint: Nicholas was resourceful in his efforts to protect the lives of the defenseless. On one occasion he prevented the execution of three young men who had been condemned. In icons we find him in his bishop’s robes, grasping the executioner’s blade before it can fall on one prisoner’s neck. It’s a story that has the ring of truth. The miracle here is the saint’s courage. Christ’s mercy shines through Nicholas’s act of intervention.

Various icons bring together saints and beasts. In icons of Saint George’s combat with the dragon, the legend has it that George only wounded the dragon, subduing it. The princess whose life was saved leads the dragon away like a pet, with her girdle as a leash. Afterward the local people accepted baptism and cared for the pacified dragon until it died. It’s a deeply Christian story even though Saint George never saw a dragon – the legend arose centuries after his death. The actual miracle in George’s life was his courage in publicly confessing his Christian belief during the persecution of Diocletian. The dragon symbolizes the fear he overcame; the princess he saved and the baptized people in the town represent all those brought to salvation by the young martyr’s act of witness.

If saints battled dragons who were really invisible demons, the wolf we sometimes see in images of Saint Francis of Assisi was probably real. We know from the oldest collection of stories about his life that he was asked by the people of Gubbio to help them with a wolf which had been killing livestock. Francis set out to meet the wolf, blessed it with the sign of the cross, communicated with it by gesture, finally leading the wolf into the town itself where Francis obliged the people of Gubbio to feed and care for their former enemy. It’s a remarkable but not impossible story. In the nineteenth century, during restoration work, the bones of a long-dead animal, probably an enormous wolf, were discovered under Gubbio’s ancient church.

A similar image has come down from the life of Saint Seraphim of Sarov. In some icons, he is shown feeding a bear at the door of his log cabin. Deep in the Russian forest at the beginning of the eighteenth century, visitors occasionally found Seraphim sharing his ration of bread with bears and wolves. “How is it,” he was asked, “that you have enough bread in your bag for all of them?” “There is always enough,” Seraphim answered. He said of a bear which often visited him, “I understand fasting, but he does not.”

Neither Francis’s wolf nor Seraphim’s bear were storytellers’ inventions. It’s not unlikely that Jordanes was as real as Gerasimos. We can easily imagine a man so deeply converted that all his fear is burned away. Gerasimos was such a man. In fact, it has not been rare for saints to show such an example of living in peace with wild creatures, including those that normally make us afraid. The scholar and translator Helen Waddell once assembled a whole collection of such stories, Beasts and Saints. (Appropriately, our copy is scarred with tooth marks left by a hyperactive puppy who was once part of our household.)

Apart from the probable reality of Jordanes, he happens to belong to a species long invested with symbolic meaning. In the Bible, the lion is mainly a symbol of soul-threatening passions, occasionally an emblem of the devil. David said he had been delivered “out of the paw of the lion.” (1 Sam 17:37) The author of Proverbs says a wicked ruler abuses the poor “as a roaring lion and a ranging bear.” (Prov 28:15) Peter warns Christians: “Be sober, be vigilant because your adversary the devil, as a roaring lion, walketh about, seeking whom he may devour.” (1 Pet 5:8) Here the lion is seen as representing that part of the unredeemed self, ruled by instinct, appetite, and pride.

In medieval Europe, lions were known mostly through stories, carvings, and manuscript illuminations. A thirteenth-century bestiary now in the Bodleian Library in Oxford starts its catalogue of astonishing creatures with the lion. It is called a beast, says the monastic author, because “where instinct leads them, there they go.” The text adds that the lion “is proud by nature; he will not live with other kinds of beasts in the wild, but like a king disdains the company of the masses.” Yet the author also finds in the lion promising traits: lions would rather kill men than women, and they only attack children “if they are exceptionally hungry.”

However merciful an unhungry lion might be, no one approaches even the most well-fed one without caution. From the classical world to our own era, the lion has chiefly been regarded as danger incarnate – wild nature “red in tooth and claw.” And yet at times the symbol is transfigured. The lion becomes an image of beauty, grace, and courage. In the Chronicles of Narnia, C. S. Lewis chose a lion to represent Christ. The huge stone lions on guard outside the main entrance of the New York Public Library always strike me as guardians of truth and wisdom.

There is still one more wrinkle to the ancient story of Gerasimos and Jordanes. Saint Jerome, the great scholar responsible for the Latin rendering of the Bible, long honored in the West as patron saint of translators, lived for years in a cave near the place of Christ’s Nativity in Bethlehem, only two days’ walk from Gerasimos’s monastery. Gerasimos’s name is not very different from “Geronimus” – Latin for Jerome – and pilgrims may have connected the two. Given the fact that Jerome sometimes wrote letters with a lionish bite, perhaps it’s appropriate that Gerasimos’s lion, and sometimes his donkey as well, eventually wandered into images of Jerome. It’s rare to find a painting of Jerome in which Jordanes isn’t present.

Jim Forest is international secretary of the Orthodox Peace Fellowship. His books include Praying With Icons, from which this text is adapted, and The Ladder of the Beatitudes. The icon, by Emelia Clerkx, is based on a fifteenth century icon in the collection of the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.