Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Ernest Becker and Our Fear of Death

-

Singing God’s Glory with Keith Green

-

More Fish Than Sauce

-

Return to Idaho

-

The Glory of the Creatures

-

Poem: “The Path”

-

Poem: “The Berkshires”

-

The Secret Life of Birds

-

Why Children Need Nature

-

Made in the Image of God

-

The Lords of Nature

-

Editors’ Picks: The Opening of the American Mind

-

Editors’ Picks: Klara and the Sun

-

Writing in the Sand

-

City of Bees

-

Sister Dorothy Stang

-

Midwestern Logistical Small Talk

-

Covering the Cover: Creatures

-

Love in the Marketplace

-

The Elemental Strangeness of Foxes

-

Saints and Beasts

-

Astronomy According to Dante

-

The Book of the Creatures

-

Letters from Readers

-

Vulnerable Mission in Action

-

Community-Supported Agriculture in Austria’s Weinland

-

My Forest Education

-

Regenerative Agriculture

-

Into the Sussex Weald

-

The Abyss of Beauty

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

Until the 1980s, newborn babies who needed surgery went under the knife with no pain medication or anesthesia. Doctors assumed that they were too young to feel pain – or at least to feel pain the way an adult does, which, for the professionals, was the only way that counted. One 1943 study helped shape this assumption. Myrtle McGraw had pricked resting, swaddled infants with a pin and judged the children’s response to be minimal. She had pricked them, and they did not bleed.

When the babies cried and screamed as a surgeon cut into them, their reaction was dismissed as reflex, not a real experience. The babies could speak for themselves at great volume, but not in a way their doctors were willing or able to listen to.

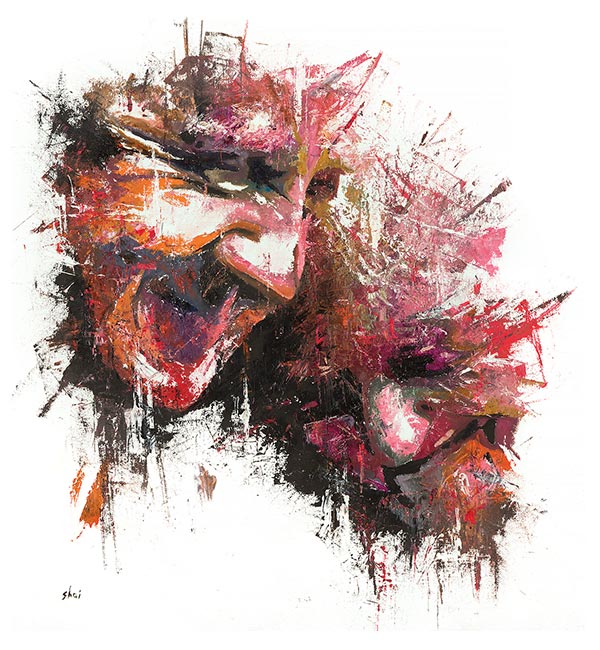

Shai Yossef, Newborn, oil on canvas

The vulnerability of our bodies is part of what binds us together into a community. In Jesus’ parable of the Good Samaritan, the story begins with the traveler’s suffering when he is beaten and robbed. His need is what calls neighborliness out of the Good Samaritan, who binds the traveler’s wounds, takes him to a refuge, and ensures his continued care.

This story is Christ’s answer to an expert in the law, who asks Jesus to clarify the limits of the Great Commandment. God calls me to love my neighbor as myself, but who, exactly, counts as my neighbor? And, left as the subtext, who doesn’t count? Whom am I allowed to not love?

The surgeons entrusted with tiny, vulnerable patients managed to pass by the babies’ need. They hurried about their lifesaving business without seeing people in their patients. There should be nothing more unignorable than a baby’s shriek, but, when we don’t believe in the dignity of the person, we find ways of denying her body and her pain.

In abortion facilities, the bodies of babies are painstakingly reassembled in “products of conception” rooms. The doctors must verify that the child is whole, before the body is thrown away as medical waste. A single forgotten limb left in the mother’s womb is an invitation to sepsis and rot. A body ignored is corrosive.

Our bodies are a brute fact. The immediacy of a sprained ankle is an aching interruption to our routines, our sleep, our thoughts. Chronic fatigue poses a constant question: If I do this, how will I pay for it later? But to get help from others, we have to find a way to cry out so that our neighbor will hear us.

Babies are too young to be able to match the expectations of the people who care for them. They are starkly honest. But, as we grow up, only some bodies will be heard and recognized by people in power. Women, people of color, the disabled all find themselves needing to translate their experience in order to be heard.

Making our internal experience externally legible may mean leaving out details, playing up to stereotypes, or otherwise matching what our neighbor expects to hear, whether or not it matches what we need to say.

Legibility, in this sense, is a concept popularized by James C. Scott in his 1998 book Seeing Like a State. He describes legibility as a central problem in statecraft – the larger the state, the more effort it must put into being able to standardize its people so that they can be “seen” by the state apparatus.1 Legibility is why states assign last names to people who previously lacked them or addresses to locations that were described solely by reference to local landmarks.

Scott is suspicious of projects to render people and places legible, finding that they often oversimplify and flatten natural relationships. A planned, gridded forest may suffer soil collapse due to the lack of complementary plants which were treated as irrelevant weeds. Scott recommends cultivating a degree of illegibility, in order to remain more independent of state programs and oversight.

Unchosen illegibility, however, means being overlooked. Women are not more free because they are less thought of. In Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men (2019), Caroline Criado-Perez assembles a long list of places women’s bodies and women’s needs are ignored. Bricks are sized to be easily held and handled by a man’s larger hand. Drug dosages are calibrated to men’s larger bodies, leaving women overmedicated and struggling with side effects. Even car voice assistants (with their deferential female speech patterns) are tuned to hear male voices. Criado-Perez coaches her own mother to lower her voice into a male register in order to be heard by her car’s computer.2

We are made in the image of God, and some part of him is denied when the goodness of the people he has made is denied.

When confronted with this problem, one auto parts executive suggested that “many issues with women’s voices could be fixed if female drivers were willing to sit through lengthy training,” as Autoblog put it in 2011. In this view, the onus is on women to change for the technology, rather than the other way around.

Altering your voice might seem a trivial example, but this is the least of the ways society pressures women to alter themselves to meet others’ expectations. From unrealistic beauty norms to unnatural footwear, the ways in which women are asked to change their bodies to fit expectations can seem unending. For those with the time, money, and genes to pursue it successfully, this strategy can be effective, but is also exhausting. It requires us to be untruthful, or at least only partially truthful about who we are. We are made in the image of God, and some part of him is denied when the goodness of the people he has made is denied.

Shai Yossef, Sisters, oil on canvas

Suffering Correctly

In his provocative 2010 book, Crazy Like Us: The Globalization of the American Psyche, Ethan Watters argues that some mental illnesses take their shape from the expectations of the culture. Anorexia, schizophrenia, and post-traumatic stress disorder are more like grief than like a physical ailment such as gangrene. All people grieve, but the form that mourning takes varies by culture. In the United States, we often wear black to a funeral, while in China, the funereal color is white. Jews traditionally rend their garments while sitting shiva, while Victorians had a half-life to their mourning clothes, fading from black to grey to mauve. The clothes make our sorrow legible to our community.

Watters argues that certain disorders are a way of giving voice to anguish in the language it will be heard in. His aim is not to explain away mental illness – the disorder gives voice to something real – but he believes we teach each other how to suffer, just as a community creates norms around mourning. And in an increasingly globalized world, America has, in the guise of aid, been homogenizing the world’s experience of pain, flattening foreign bodies to make them legible to our doctors.

In one of his examples, American medical expectations touch off an anorexia epidemic in Hong Kong. A well-publicized case of a fourteen-year-old who starved herself to death in 1994 prompted a comprehensive program to raise awareness of the disease, and succeeded too well. Dr. Sing Lee, a specialist in eating disorders, had previously seen two to three anorexic patients a year, but, after the publicity blitz, he began receiving that many referrals a week.

His patients’ experience of their disease had changed as its prevalence increased. Initially, the rare anorexics he saw didn’t know there was a name for their condition. They told him that they couldn’t eat, not that they feared being fat. They could accurately describe and draw their bodies, instead of holding on to a distorted self-image. But as the disease was publicized, the women he saw fit the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders’ criteria more and more closely.

Shai Yossef, Love, oil on canvas

It’s no coincidence Watters saw this dynamic play out in anorexia, which is most prevalent among women. Women are particularly vulnerable to pressure to make their ailments conform to expectations. Watters cites Canadian scholar Edward Shorter’s theory for this pressure to conform. As Watters explains it, “People at a given moment in history in need of expressing their psychological suffering have a limited number of symptoms to choose from – a ‘symptom pool.’”3 Without actively intending it, people in distress rely on our expectations of illness to find a way of being recognized.

My own middle-school health classes veered close to this approach. With the best of intentions, the teachers gravely instructed us that many girls experienced disordered eating, that high-achieving girls might be drawn to calorie-counting as one more thing to excel at, that it could be an exhilarating way of experiencing control if you lacked it elsewhere. It became a tutorial in how to suffer correctly.

Without actively intending it, people in distress rely on our expectations of illness to find a way of being recognized.

Today, a girl who experiences trauma or distress as her body changes, her desires stir, and men sexualize and harass her is more likely to be told that one option from the symptom pool is to not be a woman. In those same health classes, she may be told that discomfort with her changing body is evidence she might belong in a different body. In Prospect, Emma Hartley considers the flip in gender dysphoria referrals from 75 percent male to 70 percent female in less than a decade and explores what pressures and prejudices may contribute to this trend: “This is a story that needs to be understood at the level of society, not just the individual psyche.”

This theory of gender is just an update and expansion of what women have been hearing for years – that our bodies and our selves are the problem; that when there is a mismatch between us and our society’s expectations, it is we who have to change.

Women routinely alter their bodies to fit these expectations. They dye their hair and receive cosmetic injections in order to avoid the appearance of aging. Women take contraceptive pills to avoid the natural hormonal cycle, and the risk of pregnancy, instead existing in a chemical state corresponding to perpetual pregnancy (minus the baby). Over one in five American women over forty report that they took antidepressants in the last thirty days, more than double the rate of American men. To fit the space allowed, women change their appearance, their bodies, their feelings.

Escaping Expressive Individualism

There is one further demand placed on women and others who don’t fit the “standard” body. They are asked to accept this burden of reshaping themselves as an opportunity for empowerment and self-expression.

In What It Means to Be Human: The Case for the Body in Public Bioethics (2020), O. Carter Snead traces changes in how we view the body, particularly in bioethics. He sees a conflict between two claims about the source of human dignity: is our worth rooted in our existence as living bodies, or as disembodied wills?

If we are primarily wills, the human person is valuable because of his or her ability to choose. Snead refers to this ideology as “expressive individualism.” Former Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy’s decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey was rooted in this understanding of human worth. In Kennedy’s sweeping declaration, “At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.”4

This perspective promotes a kind of navel-gazing. “Flourishing is achieved by turning inward to interrogate the self’s own deepest sentiments to discern the wholly unique and original truths about its purpose and destiny,” as Snead puts it. “The truth about the self is thus not determined externally, and sometimes must be pursued counter-culturally, over and above the mores of one’s community.”

The model of expressive individualism sanctifies nearly any choice. In this framework, abortion is liberation for both mother and child. The Planned Parenthood slogan “Every child a wanted child” confers a peculiar dignity on survivors of a pro-choice world – unlike their aborted brothers and sisters, they were chosen.

This emphasis on choice puts a heavy burden on pregnant women. The unplanned, unasked-for child is cast as a failure, along with his or her mother. In an essay for The Atlantic, Sarah Zhang counted the cost of Denmark’s universal screening for Down syndrome. Having more information made some families feel worse than if they were being kept in the dark.

The introduction of a choice reshapes the terrain on which we all stand. To opt out of testing is to become someone who chose to opt out. To test and end a pregnancy because of Down syndrome is to become someone who chose not to have a child with a disability. To test and continue the pregnancy after a Down syndrome diagnosis is to become someone who chose to have a child with a disability. Each choice puts you behind one demarcating line or another.

When their child was a choice, for parents to have or abort a child with a disability became part of their expressive identity. If their child had been disabled after birth in an accident, the parents would not feel that everyone who knew them looked at their child’s condition as a choice that the parents had made. It would be simply who their child was.

Snead sees an alternative to expressive individualism – valuing the givenness of our bodies as they are, in all their vulnerability and weakness. In our fragility, he sees proof that we are relational beings.

Because human beings live and negotiate the world as bodies, they are necessarily subject to vulnerability, dependence, and finitude common to all living embodied beings, with all of the attendant challenges and gifts that follow.… Given the way human beings come into the world, from the beginning they depend on the beneficence and support of others for their very lives.5

Women are bound more tightly to this truth, even when society asks them to deny it. Not every woman will bear a child, but every woman lives with an awareness of her potential for new life, whether she experiences it as a gift or a threat. Even a planned, chosen pregnancy is a tutorial in the limits of the will.

It seems that won’t stop people from using every technological advance at their disposal to bypass those limits nature would impose. In the world of assisted reproduction, meanwhile, the primacy of will radically reconfigures these embodied relationships, parceling out roles – egg donor, gestational surrogate, etc. – that multiply parents while muddying their connection and duties to the child.

Shai Yossef, Touchdown, oil on canvas

Surrogacy contracts assert the rights of the parents to kill their child, even over the objections of the woman who is, moment by moment, sustaining that child. Parents might demand abortion as a resolution to a higher risk pregnancy of twins or triplets, or upon learning that their child carries a congenital abnormality. Their contracts claim that they have the higher claim on their child than the unrelated woman whose body has remade itself to help the baby grow, who to them is merely a commodity. To be a parent, in this understanding, is to have the authority to destroy.

In one case, when a surrogate named Melissa Cook offered to adopt the unwanted triplet rather than allow it to be killed, the father objected, out of a sense of justice. As Katie O’Reilly reported for The Atlantic, “The father of Melissa Cook’s fetuses has stated that he believes singling one child out for adoption would be cruel, and thus he prefers to reduce.” He did not want to let one child live unchosen – judging it better to not be.

Every body is a testimony: we are made in God’s image.

In such cases, a child who does not match our expectations or plans for our expressive identity may be deprived of life. After birth, people who don’t fit in neatly may not face death but may still be negated, forced to be less themselves to be “allowed” to take up space. And, in countries with expansive euthanasia regimes, some people keep hearing the suggestion that suicide is the solution to the problem of their presence.

The narrower our ideas about whose bodies matter – who is our neighbor – the less likely we will be to help, love, or even see others. And with the body unacknowledged, it is easier to overlook the more permanent but more elusive soul.

Every body is a testimony: we are made in God’s image. Our frailties reflect his commandment that we must love each other as he has loved us. When we marginalize our neighbors, we blot out that image and refuse the duty of that commandment. A woman’s body, accordingly, does not need to be rewritten – women must be seen and loved as women. When we fail each other in this duty of love, our neighbor’s body testifies against us.

Footnotes

- James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed ,Yale University Press, 1998.

- Caroline Criado-Perez, Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men Harry N. Abrams, 2019.

- Ethan Watters, Crazy Like Us: The Globalization of the American Psyche (Simon & Schuster, 2010), 32.

- Anthony M. Kennedy, Planned Parenthood v. Casey majority opinion, 1992.

- O. Carter Snead, What It Means to Be Human: The Case for the Body in Public Bioethics, Harvard University Press, 2020), 88.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Mike Frank

I liked very much your issue on Creatures. The article by Leah Libresco Sargeant was especially fine. We are, indeed, created in the image of God. And the revelation and fulfillment of that image is found in the Incarnate Son of God. Indeed, it is there that we find ourselves and our neighbor, that we understand them (and ourselves) as valuable and of inestimable worth because the Son of God was made incarnate for them (and for us). Far from allowing us to impose a false criterion on our neighbor, which if not met devalues them, the incarnation now calls us to see and understand our neighbor as those whom God has loved and valued in the sending of His Son. Furthermore, it is in the incarnate Son of God that we find our true identity and the identity of our neighbor, just as Paul describes in 2 Corinthians 5. Thus we understand that racism really is a kind of blasphemy, as is the act of the destruction of an unborn child These acts are finally a denial of the incarnation.

Susan

Have just returned from Jamestown where in 1662 they decided, under pressure from the mercantilists, that the baby's "status" follows that of the mother. This kicked off eugenics and the reworking of *all*of us into "creatures of the state", the Africans only more obviously. Until "created equal" was pronounced, giving the promissory note against slavery, abortion, and Frankentube conception.

Jacqueline Watson

I found "Let the Body Testify" the most provoking probably because I am a Mother. At one time I did think that abortion should be given to women who were made pregnant through the act of rape and children with profound disability. I grew up and realized the child is not to blame and has every right to life and have their own gifts to share. I had a good pregnancy until the end when I was given a C-Section to allow our son into the world nearly 50 years ago. He is healthy has brought great joy and is now a worship leader in his church with a lovely wife and daughter. Perhaps 80 years ago I would not have been so lucky and we would have both died. I find surrogacy difficult to come to terms with, how can you give up a child you have carried for nine months or if something has "gone wrong"have to watch that child be destroyed? There are children who need loving families to adopt them. Not everyone can have a child but there are other children around who need our love. Yes we were lucky and had a boy but I would be just as happy if he had been a girl and I told him when he was expecting a baby we would be happy what ever sex and didn't expect him to produce a boy "to carry the blood line"! Why do women have to be made to feel as though it is their fault if they have a girl and are kept permanently pregnant until they have a boy?

Israel Steinmetz

I was so encouraged to read Leah Libresco Sargeant's article in Plough. What an important foray into the intersection of female bodies and unborn bodies. In a cultural climate where Christians are often pressured to follow one or another political agenda that would value either women's bodies or unborn bodies, we desperately need voices like Leah's to call us to a comprehensive and Christo-centric ethic of bodies. I am often a source of confusion to many of my friends, both Christian and otherwise. Perhaps the paradox is best observed each year when I share pictures of my family and I participating in a Martin Luther King Jr. Day March in January and then in a Sanctity of Human Life March in February. In a nation where many Christians are discipled in social ethics by competing political parties or cable news outlets, someone who cares equally about racism and abortion tends to be looked at sideways. But what if we let the teaching of Christ and the Apostles guide our ethical reasoning? What if the same impulse that causes pro-life people (like me) to cry out for the lives of innocent, unheard, oppressed, unborn human beings who are killed everyday because they're denied the legal protection of personhood also caused pro-lifers to address the sanctity of life when it comes to sexism, the environment, racism, classism, the economy, war, and criminal justice? Similarly, what if those who espouse liberal principles of dignity, equity, and justice (like me) allowed the same impulse that causes liberals to care for the weak, voiceless, and marginalized who have already been born to extend that exact same logic and compassion to unborn human beings? If bodies matter, how can we claim that another person's body, with its own parts and DNA, does not matter because it is housed temporarily in the body of another? "My body, my choice" makes little sense when we're talking about the body of another human being housed within one's body. How can we use "viability" as an excuse to kill a person once we've recognized how interdependent the human family is upon each other to survive and thrive? Is a person's life really worthless because the natural stage of development they are in requires them to live in their mother's body and depend upon her body for sustenance? If so, why does this arbitrarily change once they're born and continue to be absolutely dependent upon their mother (or surrogate) for care and nourishment? Is breastmilk that different from amniotic fluid? Is the warm embrace of a mother's arms that different from the warm embrace of a mother's placenta? I'm pro-life when it comes to abortion for the same reasons I'm pro-life when it comes to healthcare, the environment, economics, criminal justice, equity, etc. Pro-choice liberals are right to criticize "pro-life" Christians who advocate for unborn babies but support a culture of death through mysoginy, inequality, war, racism, ecological classism, and the death penalty. And pro-life Christians are right to criticize "pro-choice" liberals who advocate against oppression, inequity, injustice, and exploitation but support the killing of human beings simply because they have not been born. Pro-life and liberal ideals of human dignity only makes sense if they acknowledge and care for the value, dignity, sanctity, and worth of life from conception to natural death. Pro-life and liberal only make sense together, not when pitted against one another. As Christians, can we allow our beliefs and practice to be formed by the teaching of Christ and the Apostles in Scripture rather than our political party of choice? Can we see the image of God in every human being, regardless of their age, stage of development, ability, color, ethnicity, nationality, gender, sex, guilt or innocence, sexual orientation or gender identity, socio-economic class, etc? May it be so in Jesus' name.

Rowland Stenrud

We shouldn't be surprised by the problem called gender dysphoria. God made us from the dust of the ground. Therefore, we human beings were never the perfect image of God who is Pure Spirit. We are spirit beings with animal bodies, animal bodies that can be injured and killed and get old and die. I don't particularly like being a spirit being trapped in an animal flesh and blood body, whether male or female. It is our animal bodies that is the problem and not being either male or female. But I don't agree with the ancient Gnostics some of whom taught that the god of the Genesis creation was an evil god who put the spark of the human being in an animal body. God did a good thing by putting us humans into an animal body. By having an animal body we human beings gain knowledge of good and evil especially of our own good and evil. If we had imperishable spirit bodies, we could not see the evil of our lack of love for our fellow human beings or of a lack of love for God. The murderous thoughts in our souls would not result in killing our fellow human beings. Our selfishness would not result in our indifference to the suffering of other human beings. Human beings would not starve to death due to our indifference. We would not have to sacrifice our lives out of love for a sick person who needs our constant time and attention. The evil of war would be impossible because no weapon could kill our enemies. Our animal bodies are the source of our knowledge of good and evil. God's work of saving us human beings is a creation work by which we are perfected in love. The crucifixion of Yeshua was a creation event in which Yeshua was perfected in love by his suffering per Hebrews 2:10; 5:8-9; 7:11 etc. Yeshua in going to the cross was perfected on our behalf, not punished on our behalf. The resurrected Yeshua of Nazareth was the first human being made in the perfect image of God. With the Spirit of Yeshua living in us we too become like him in love. Our salvation is completed by our resurrection. The resurrection of the human being is a creation event in which the human being becomes made in the perfect image of Yeshua and thus in the perfect image of God the Father. We human beings will have spiritual bodies that are in accordance with our spirit selves: "So is it with the resurrection of the dead. What is sown is perishable; what is raised is imperishable... It is sown a natural body; it is raised a spiritual body... The first man Adam became a living being; the last Adam became a life-giving spirit.... Just as we have borne the image of the man of dust, we shall also bear the image of the man of heaven” (1 Corinth. 15:42, 44, 45, 49). Theologians have improperly emphasized the FALL of man, his sin. Adam and Eve were of dust before their fall. Their sin against God and one another showed that they did not have the power to love. They needed Yeshua and his Spirit before they sinned. They sinned because they did not have Yeshua. Yeshua the Messiah was always God's Plan A for the creation of man in God's perfect image. Yeshua was never God's Plan B in case Adam and Eve sinned. Adam showed is lack of love for Eve when he blamed Eve for his sin of eating from the forbidden tree. Eve showed her lack of love for Adam when she asked him to join her in eating from the forbidden tree. IF Adam and Eve had been the perfect specimens of humanity they would not have sinned. PERFECT PEOPLE DO NOT SIN!!! This should be obvious. Our animal bodies make it possible for us to suffer. The forbidden tree, The Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil could be named The Tree of Suffering. For this knowledge is experiential knowledge, not simply intellectual knowledge. We know the good things through our corporeal existence as well as the bad things. When Adam and Eve rebelled, God did not have to make any change to their corporeal existence for them to experience suffering and death. All God had to do was to keep them from eating from The Tree of Life. When we human beings are created in God's perfect image we will not need The Tree of Life. We will have the fulness of life within ourselves as God has. See John 5:26. Eternal life is far superior to the immortality that Adam and Eve would have had they not rebelled against God, a rebellion that was unavoidable because Adam and Eve at their creation were the natural man: "The natural man does not accept the things of the Spirit of God, for they are folly to him, and he is not able to understand them because they are spiritually discerned... " (1 Corinth. 2:14). For some mystery of creation, God is not able to create perfect human beings who are his perfect image without us human beings experiencing suffering and moral failure along with joy and love. We all learn the lessons we need to learn from one another in this imperfect life in animal bodies.

Bob Laver

This great article reminded me of more and more forgotten people.. If we are to be completely pro-life, then we need to accept, value and nourish all life from conception until death regardless of their age, sex, race, nationality physical and mental health or appearance, In short, all people are created in the image of God and are to be valued and cherished. The world would be a lot better place if we all did this.

Jean-Paul Marie Justin

Child of the 60's that I am, I bore witness to emergence of Civil Rights, the Peace Movement and Nonviolence as a changemakers path. I am sad to say that what was a rebellion against Hypocrisy, has devolved across time into a slim - shadey legacy of sex, drugs and rock and roll. Why? because we failed ourselves. We failed because with Freedom, comes responsibility and sooner or later -- accountability. With freedom, we began to treat our bodies as property. It was the model most loudly represented, bodies as property. Bodies to be used, abused, and discarded. For women, our bodies were no longer property of men -- rather our bodies were now our property to be nipped and tucked, tipped, twisted and tattooed. We starved, we stuffed, we drugged, we drank -- and yet if we were to witness someone doing to a child what we now feel free to do our "bodies as property" -- someone would video it, and call for an immediate intervention. We are free to do what we want to property -- free to take a baseball bat to our automobile, paint it, put junk in the trunk and in the tank. But do we recognize when we are doing the equivalent to our bodies? And here is the tough one -- do we recognize when we are treating the womb and the fruit of our bodies as property to be rented out, or sold or destroyed -- because that is what an owner can do with property. I am old now. And I remember all the ways I celebrated freedom, and peace without ever recognizing the abuse of power, the violence I committed against my body. I am, all these decades later, learning how not to treat my body as property. I'm faced with "parts replacements" now! Looking for donors when this or that wears out. Because, in this first world sense of importance I've been taught that I am more important, more valuable as a bodily fact than __________(fill in the blank). I ask the generations who leaned into our example to forgive me, for failing them in ways I couldn't even imagine then. When the suppressions and oppressions stepped back, I didn't want to take responsibility for my impulses, I didn't want to take responsibility for the consequences for my failure to curb my ego for the sake of you. Truly, I say to you, with freedom comes responsibility and accountability, the future depends on your embrace of that reality.

Katherine H Dinsdale

Congratulations on a thoughtful and provocative story.

Ruth Worman

I must take issue with Leah Libresco Sargeant's alarmist interpretation that trans men are really just women who have not been supported in loving themselves and their bodies. Has she spoken with actual trans men - really listened to her neighbors in how best to love them - or just relied on a similarly alarmist article (Emma Hartley in Prospect) drawing on a trend in the UK (with few data points for comparison) and a few anecdotes to make the point? Another article from the same date/ same magazine refutes Hartley's assertions, testimony from an actual trans man with 45 years' experience working in the community, and mentioning actual scientific findings about differences being discovered in brain structure among trans people. I'm deeply disappointed in this article. I expected better from the Plough.

Heather Mistretta

What a powerful article- thank you!

Jacob Taylor

Thank you so much. I enjoyed the read and this is necessary in our age.