Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Covering the Cover: Beyond Borders

-

Choosing America

-

Church as Sanctuary and Shelter

-

Northern Ireland’s New Troubles

-

When Migrants Come Knocking

-

The Florentine Option

-

Three Kants and a Thousand Skulls

-

The End of Rage

-

Telling a Tale of Two Fathers (Video)

-

Home Is Not Just a Place

-

The Quest for Home

-

In Search of Lost Fig Trees

-

Child of the Stars

-

Refugee Letters

-

Life in Zion

-

How to Run a Cemetery

-

Integrity and the Future of the Church

-

Daring to Follow the Call

-

Poem: “For the Celts”

-

Poem: “Wreathmaking”

-

Poem: “The Hunger Winter, 1944–5”

-

Editors’ Picks: The Cult of Smart

-

Editors’ Picks: The Utopians

-

Editors’ Picks: The Lincoln Highway

-

Casa de Paz

-

The Pilsdon Community

-

Letters from Readers

-

Nonexistence Does Not Scare Me

Toyohiko Kagawa

Pacifist Patriot, Christian Socialist, Incendiary Peacemaker

By Susannah Black Roberts and Jason Landsel

August 20, 2022

Available languages: 한국어

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

This article was first published in the Autumn 2021 issue of Plough Quarterly.

On Christmas Eve, 1909, Toyohiko Kagawa, a twenty-one-year-old seminarian, moved into the Shinkawa slum district of Kobe, Japan, to share a home with down-and-outs, feeding them from his student stipend.

The illegitimate son of a samurai, Kagawa had been orphaned at age four. At school, he was welcomed into the households of American Presbyterian missionaries. Their love, and love of learning, was infectious. “For the first time,” Kagawa recalled, “I began to awaken to a sense of being alive.” He read Ruskin, Tolstoy, and the Bible.

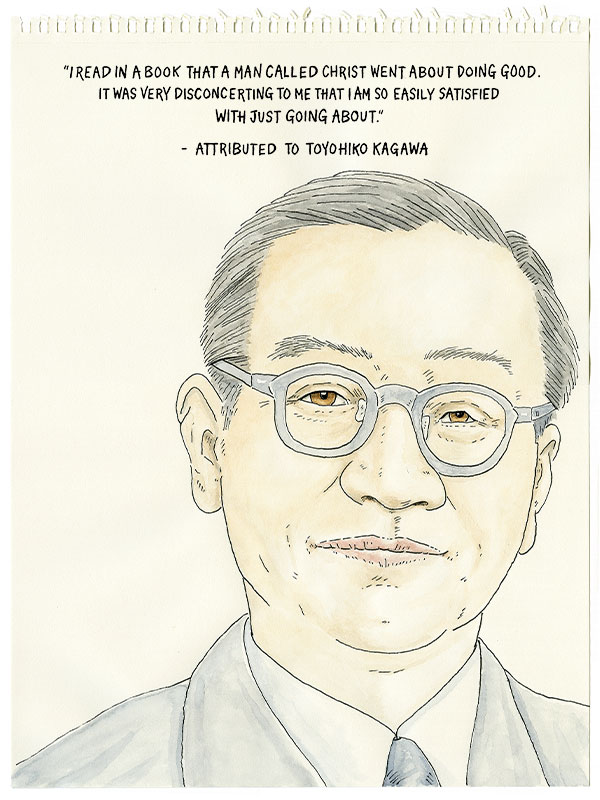

“I read in a book that a man called Christ went about doing good. It was very disconcerting to me that I am so easily satisfied with just going about.”

—attributed to Toyohiko Kagawa

Kagawa became convinced that he had to care for the poor personally. But after moving into the slum, he realized that this would not be enough. How could he help demoralized people want to take care of themselves? How could the economy be changed so people would have a chance to thrive? What could he do to keep families together so children would not grow up without love?

Kagawa found a wife, Haru Shiba, who shared wholeheartedly in his ministry. When their first baby came along in 1922, they moved out of the slum, where infant mortality was 75 percent. But Kagawa continued tirelessly organizing and writing. Inspired by English guild socialism, he focused on building worker cooperatives and labor unions. And he became active in the international peace movement, speaking out against militarism and imperialism.

Still, Kagawa considered himself a patriot. After Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and the United States entered World War II, he made radio broadcasts condemning American barbarism while failing to similarly condemn Japanese atrocities. Even so, his record of pacifism, such as his public apology to China for Japan’s invasion of Manchuria, made him suspect, and he was arrested twice for “antiwar thoughts.”

Toyohiko Kagawa Artwork by Jason Landsel

With the US nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the war was over. In February 1946, a much-diminished Emperor Hirohito, no longer officially considered divine, called Kagawa to the Imperial Palace. “Whoever wishes to be great among you must become the servant of all,” Kagawa advised, quoting Jesus. “A ruler’s sovereignty, Your Majesty, is in the hearts of his people. Only by service to others can a man, or nation, be godlike.”

As an adviser in the postwar reconstruction, Kagawa saw many of the reforms he had sought realized – legalized unions, redistribution of land, worker cooperatives, and women’s suffrage. It took losing the war that had compromised his mission for that mission to be fulfilled.

Kagawa wrote more than one hundred fifty books, including bestselling novels. He was twice nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature, four times for the Nobel Peace Prize. A pacifist patriot, a socialist Christian, and an incendiary peacemaker, he wasn’t always the saint he was made out to be. But he never lost the conviction that because God cares for each person, so must we.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.