Subtotal: $

Checkout

At the Mercy of the Winds

Are the winds ancestral gods or natural resources? The Wayuu indigenous in Colombia have mixed feelings about new wind farms on their lands.

By Weildler Guerra Curvelo

October 10, 2022

Does transitioning to renewable energy sources show sufficient creation care? At the northernmost tip of South America, indigenous people have questions for green-energy multinationals building wind farms on their reservation.

Within a log enclosure, a group of Wayuu women protect their fire and food from the sand and wind. They will be busy all morning preparing goat stews and chicha, a refreshing corn drink. Their voices ring with the musicality of their language, Wayuunaiki, which has resounded here for centuries. The winds comb the tops of the trupillo mesquite trees and agitate the tiniest bushes along the paths. Strong wind and blinding light are ever-present in this semi-arid region of Colombia’s Guajira Peninsula, the northernmost tip of South America. This morning in March 2022, in the indigenous neighborhood of Talouloma’ana, leaders from all over the territory are meeting to discuss other kinds of winds – the winds of uncertainty.

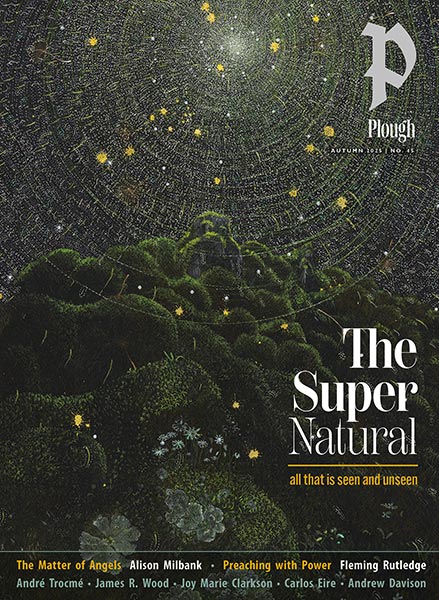

Wayuu women prepare food in a traditional kitchen. All photographs by Andrés Cardona. Used by permission.

At one time, Talouloma’ana was a shantytown outside Maicao, the second largest city on the peninsula. But Maicao’s unstoppable spread has absorbed Talouloma’ana, whose houses are now a blend of modern urban homes and traditional shacks with their outdoor kitchens under thatched roofs. There are more than 380,000 Wayuu in the Colombian part of the Guajira Peninsula, which also lies partly in Venezuelan territory. In rural areas, they make their living grazing livestock, hunting and fishing, mining salt and working smallholdings. In urban areas, many are taking up wage labor and commerce. Water is scarce on the semi-arid peninsula. Just 20 percent of the inhabitants had access to potable water in 2020, and 23 percent of malnutrition-related deaths among Colombia’s minors occur there.

This morning, the indigenous delegates are distressed about new wind energy projects proposed by the Colombian government. Some are already underway near Cabo de la Vela, a neighboring region known for its virgin Caribbean beaches which is also home to many Wayuu sacred spaces. With the inauguration of the windfarm “Guajira I” in January 2022, a ten-turbine installation generating twenty megawatts and covering 5.5 hectares, then-Colombian president Iván Duque announced the construction of sixteen more over the next three years.

Many Wayuu communities disagreed with these plans because the government neither included them in the planning nor informed them fully of the risks, even though the turbines will be erected on indigenous land. Clean energy infrastructure can also have environmental and social impacts in the areas where it is installed, and the Wayuu have many questions. Are the companies taking measures to preserve important sacred sites? Where are the studies on the environmental and social impacts? And what are the benefits of these projects? These are all crucial questions for peoples who hold painful memories of past development projects that did not benefit the local people.

One of the meeting’s participants is Guillermo Ojeda Jayaliyuu, secretary of the Major Autonomous Board of Palabreros. Palabreros resolve family and tribal indigenous disputes through their restoring, peace-bringing words. At the foot of a large trupillo tree, we asked Guillermo what the winds mean to the Wayuu. He talked about the need for open spaces, like the wall-less rooms attached to Wayuu homes from where the horizon is always visible. The palabrero’s words, which are foundational to the Wayuu society, cannot be spoken within an enclosed building because they require continuous, visual contact with other living beings, like trees and landscape features. “The winds are ancestral, guardian entities in Wayuu cosmology,” Guillermo continues. “The wind, together with the sun and the moon, was responsible for all the living things in the territory. It maintains the equilibrium. We know that the wind’s paths run through this territory and that the multinational corporations have decided to harness its lifegiving force. But the turbines will disrupt the wind’s path, causing an imbalance. They will disturb the sacred places where medicinal plants grow.”

Leaders of the Wayuu Nation, Board of Palabreros and the Force of Wayuu Women meet to discuss the proposed wind farm projects.

Enrique Cohen Hernández, an elderly man from Upper Guajira, expresses his sorrow and distress over the wind farms. He worries that the vegetation will retreat when concrete bases are constructed for the hundreds of turbines in the sixteen wind farms. This will cause a massive displacement of the Wayuu, a pastoral people with thousands of goats, sheep, cows, and horses, because their animals will no longer have places to graze. “The wind is life,” he says. “It is what bathes our lungs, it is spirituality, it is feeling. There are wind farms or there is life; the two are not compatible. We live because the wind is with us. This land does not belong to Colombia, nor to Venezuela, but to the Wayuu. It would be an extreme error to insist on installing these wind farms in sacred places. It’s disrespectful; it would be like building a wind farm in the Vatican.”

In a July 2021 ceremony marking the delivery of the blades destined for “Guajira I,” president Duque signaled that the peninsula would become Colombia’s “gateway to renewable energy.” Like other countries, Colombia has proposed gradually substituting fossil fuels with cleaner sources of energy like wind, solar, and geothermal. Besides the Colombian Isagen Empresas Públicas de Medellín, corporations from Italy, the United States, Germany and Austria are in charge of different projects as part of this energy transition. But the scene is a Babel, with each project negotiating separately and reaching agreements under different terms – often unjust – with the Wayuu communities.

Some of the communication difficulties may be because the two parties are talking past each other. Institutions like the World Bank have accumulated experience from wind projects around the world. They have studied the impact the projects have on birds and bats, which can collide with wind turbines, as well as the effects of noise from the turning blades. They also warn of a loss of habitats because the need to “clean up” vegetation around the planned wind farm can pose an important risk to biodiversity. There are other obvious effects, such as a “shadow flicker”: an irritating, blinking effect caused by the blades turning in bright sunlight. But there are no studies on how these gigantic towers will alter cosmologically significant geographic features. Mountains, rocks, and water sources are an important part of Wayuu communication with the divine. This rupture of the land itself will alter the spiritual intelligibility of the territory, raising the possibility of significant cultural suppression.

Guajira I wind farm, in operation since January 2022, is the first to come on line since Jepírachi in 2004. Both are located near Cabo de la Vela, traditionally the place where Wayuu souls travel after death to find the gateway to the afterlife.

As the morning goes on, we talked with Álvaro Iguarán Uliana, a seventy-year-old Wayuu commercial leader. Because of his experience with customs regulations, he has participated in multiple negotiations with national governments. In his opinion, the agreements between the corporations and Wayuu families are extremely unequal. “The government and corporations arrive with teams of specialists and professionals,” he explains. “The Wayuu are left negotiating with little-to-no advice. The corporations unilaterally establish the conditions of shareholding and profit sharing. The losses are immense and uncompensated. There is no legal framework for agreeing to cut down a trupillo tree, a medicine tree, a tree that helps feed the animals. How are they going to compensate for that? They haven’t considered the loss of natural pastures or the spiritual dimensions, like what will happen to the wandering spirits of the dead.”

Just before noon, the kitchen’s irritating smoke wafts towards us. We move near the school to talk to Andrónico Urbay Iipuana, a distinguished member of the Board of Palabreros. A middle-aged man who wears a traditionalhat, Andrónico is the mediator between the special jurisdiction of the Wayuu and the Colombian judicial system. By his assessment, the arrival of the multinational corporations is a direct blow to his people. “These complexes are going to cover a lot of lands and will hem the Wayuu in. There have been many dirty tricks. The consultations have been unequal. This will cause population displacement. No Wayuu can live without land; he or she would become blind, or invalid. This is a massive attack on the Wayuu way of life, because it threatens five protected aspects of our culture: our native language, land, social organization, economy, and spirituality.”1

In the opinion of most indigenous leaders interviewed for this article, some families are negotiating to stave off starvation. The corporation offers them a few provisions – animals and corn – whose usefulness to the living will vanish as rapidly as a funerary expense. It’s an unequal negotiation. There is no “shared value” policy here; only a “merciful gift.” A corporate agent confirmed with indifference that the indigenous could not possibly be partners because they did not understand losses and returns. These bad pacts could well be sowing the seeds of social tension that will erupt someday.

In July 2021, regional media reported that various traditional authorities representing their communities had blocked the road between the town of Uribia and the village of Wüimpeeshi. The protesters were demanding free, informed and prior consent to decisions concerning the land and natural environment. That December, government spokespeople announced that a special battalion of the Colombian army had been dispatched, with “mission of protecting the investment of the foreign economic corporations which have trusted Colombia enough to invest in this country.” It is clear that foreign investment is officially protected by the state. Who, then, protects the rights of the local indigenous communities?

The indigenous community of Mushalerray, located near the Guajira 1 wind farm, is divided between those who approve of Isagen’s project and those who do not.

For Andrónico Urbay Iipuana, this is a violation of Wayuu autonomy and of public law. He cites article 30 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: “Military activities shall not take place in the lands or territories of indigenous peoples, unless justified by a relevant public interest or otherwise freely agreed to or requested by the indigenous peoples concerned.” It is important to underline that these projects are occurring in the Wayuu reservation of Upper and Middle Guajira, one of the largest in Colombia. The reservation is protected by Colombia’s constitution, which establishes that indigenous lands are non-transferable communal property.

The day advances in Talouloma’ana. The morning’s clouds march on, and a sweltering sun falls over the territory. The meeting’s participants are seated in a cool, covered veranda, sharing chicha while the leaders take turns speaking.

The Colombian vice minister of energy, Miguel Lotero, has said that the construction of sixteen wind farms in Wayuu land would generate eleven thousand jobs. Nonetheless, César Arizmendi, an experienced Wayuu economist, believes the jobs will only last for the construction phase. Once the turbines are installed, they can be monitored at a distance.

Jazmín Romero Epiayu comes from the southern reservations. She is a distinguished leader from the organization Fuerza de Mujeres Wayuu (Force of Wayuu Women), a young and vehement leader on environmental issues and women’s rights. In her role as a Wayuu activist and feminist, not only has she observed the activities of wind energy corporations, but also the exploitative works of other companies. In addition to its immense wind and solar potential, the Guajira Peninsula has other valuable natural resources like carbon and natural gas, which has been divided among the multinationals. Time and again, the Wayuu have suffered loss of land, diversion of water sources, noise pollution, and accidental deaths and coal pollution along the train lines. They understandably feel they have lost control over their own lands.

Elba and Denys Velasquez Uriana live in Mushalerray, near the Guajira 1 wind farm. The Epieyu are the traditional owners of this territory, and although Elba has married into the clan, she cannot take part in decision-making here.

Jazmin’s voice and verdicts are clear and firm: “The presence of more megaprojects in our territory exacerbates the problem we have had throughout history, which we have not been able to remedy either through politics or from within our culture. There is a high risk that the territory will suffer. External forces have created disharmony on the inside which is fracturing our culture, and even our fundamental Wayuu spirituality. We have to begin by respecting Mother Earth. Her organs are these exploited resources like gas and coal, which are being sacked without her consent. Nobody has asked Mother Earth what her coal, petroleum, and gas mean to her.”

In the Wayuu worldview, Joutai (the wind) is an invisible being which represents breath, life, coolness, peace, and tranquility. Jazmín thinks that the foreigners “come for riches or for the power of Joutai or for what he provides us, which is life itself. Can we keep falling in the error of not asking Joutai how he is? And we have not told him that there is risk and asked him for wisdom. Perhaps the Wayuu, through losing their connection with tradition and adopting a Western lens, have been complicit in this whole situation.”

In Wayuu cosmology, the winds are plural beings and have distinct temperaments. Some winds are benevolent and loving, like Jepirachi, the soft, northeast wind. Others are associated with hunger and drought, like Joutai, the eastern wind, or with deception, like Jepiralujutu; there are also Tepichijua (the small whirlwind), Chipuutna (the hot, strong wind), Wa’ale (the despised wind that blows gusts), and finally Wawai (the hurricane which destroys everything).2 This begs the question: which wind will the companies be using?

The Lanshalia indigenous community is located near Guajira 1 wind farm. Many of the elders who approved the project have died, and some communities are requesting new consultations. Inter-clan disagreements over the project have been escalating, resulting in several casualties.

Like the winds, the corporations are myriad. According to the Wayuu lawyer Griselda Polanco, “some corporations respect the advance consultations and the discussions that had with our elders on ancestral grounds, but there are others who totally neglect their agreements and disrespect our grandfathers. I think there are few that are honoring their agreements. This has led to warring between Wayuu families. The companies are exploiting the lack of government presence and violating indigenous rights. They wrongly go after people who have assessed the proposed impact of the projects, and trample on the rights of the elders, which they are not aware of.”3

José Luis Iguarán, a representative from an area that already has a wind farm, is happy with the agreement reached with Isagen. Negotiations began in 2009, and both sides have kept up open communication. The key, he thinks, is direct dialogue between corporations and indigenous groups. Isagen has given the Wayuu several benefits: a percentage of the profit from the sale of carbon certificates, 0.5 percent of the generated electricity, and compensation for the use of the territory. “If we are honest, we have enough money flowing into our community to keep up our economy, and our quality of life has improved.” He believes that the conflicts over the wind turbines arise when “the corporations do not speak with the traditional owners of the territory, but with the achón inhabitants, the children of the current male elders. Although they might live in the territory of their fathers’ clan, they have no rights to decision-making there because Wayuu society is matrilineal. We have been in dialog with Isagen some fifteen years. Today the corporations want to do this whole process in a year.”

As the meeting progresses and indigenous leaders voice their disagreement regarding the direction these energy projects are taking, I ponder that the country could take better advantage of its past experience. The first wind farm built in Colombia was the Jepirachi, constructed in La Guajira in 2004. Planning and negotiations started in 1999 and lasted until June 2002. The community assisted in the environmental impact study and in drafting a plan for environmental stewardship. The project has not progressed without tensions, including prolonged occupations of the farms by protesters, creating a valuable learning experience regarding the right and wrong ways to go about things. Now, considering the mantle of secrecy that hides the research phase, and the absence of information available to the Wayuu regarding the environmental and social impacts on their territory, it seems the country has regressed.

Evening falls in Talouloma’ana. Negotiations will continue into the next day with new delegates. I find a moment to talk with Miguel Ángel López Hernández, a locally renowned poet, writer, and Wayuu cultural ambassador. For him, the arrival of dozens of wind farms “does not represent anything new in the context of Colombian-Wayuu relations. Despite constitutional promises of Wayuu autonomy, that is not the reality on the ground. Take for example the so-called ‘preconsultations,’ where the corporations simply share information with the Wayuu instead of providing information and discussing different options. The state acts unilaterally.”

Reinaldo is a fisherman and a guide for flamingo-watchers in Laguna Grande. He is intimately in tune with the winds, since they determine his daily fishing voyage and affect flamingo flight paths.

Miguel Ángel thinks that the objective of these projects continues to be “financial gain for the owners of capital, who then deliver the dregs drop by drop to the territory’s majority indigenous population.” As we discuss the different conceptions of wind held by the corporations and the Wayuu, he is hopeful: “The project could be an opportunity for two languages to come closer together. Scientific knowledge about the winds could be reinterpreted through other kinds of wisdom. We could accept a different way, if in turn this acceptance would allow them to understand us better.”

It is time to return to Riohacha. We have learned the following key truth: the winds the Wayuu speak of and those that move corporate investment and government politics do not appear to have anything in common. It is not a simple disagreement about economic compensation. The heart of the matter is an ontological conflict, a difference regarding the nature of things. There are different notions about time, wind, plants, animals, landscape, and the rights of the beings who inhabit the land.

There will need to be new dialogs about the different ideas of Mother Earth. The Wayuu will always have the time, says the poet Miguel Ángel, to listen to others, because this is one of their characteristics as a people: “to breathe and sweat down to the roots while sighing with the opening of wings, ready for a new flight.”

The original Spanish version of this report appeared in the May 2022 edition of Gatopardo. The English translation by John B. Meyer has been lightly adapted for length.

About the photographer: Andrés Cardona is a Colombian photojournalist and documentary photographer who covers armed conflict, environment, human rights, and indigenous communities. The recipient of various awards and scholarship, his work has appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, Bloomberg, and El País.

Footnotes

- The Wayuu legal system was included in UNESCO’s 2010 Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

- For more information, see Weildler Antonio Guerra Curvelo, Ontología wayuu: categorización, identificación y relaciones de los seres en la sociedad indígena de la península de La Guajira, Colombia. Colombia: Uniandes, 2019.

- In August 2020, the Office of the General Inspector of Colombia ordered the Ministry of Mining and Energy to halt construction of a high-tension line in La Guajira because it infringed upon the rights of the Wayuu communities living near the project. Laura Vita Mesa, “Procuraduría pide suspender proyecto eólico en La Guajira por no involucrar a comunidades wayuu” in Asuntos Legales, Colombia, August 13 2020.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.