County Fermanagh, early May 2021: Hypervigilance is our default setting in Northern Ireland. When you have our history, you pay close attention to every new mural, every new poster, every newly-painted curbstone. It’s the only way to anticipate what’s coming – so when a neighbor raises a flag overnight, you don’t ignore it. One spring morning, earlier this year, I saw from my bedroom window that my neighbors had run an orange flag up their flagpole. Every year the Orange Order celebrates the victory of William III of Orange, who defeated the Catholic James II at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, so I assumed it was for that that the flag had been run up. Except no, wrong. The Battle of the Boyne was in July, which was two months away, and flags would never go up that early, I thought.

After breakfast, my wife and I set off on our morning walk. We schlepped down the frosty road and stopped to look at the flag. I saw it bore the legend, “1921–2021 Northern Ireland Centennial Flag.” Mystery solved. Today was the hundredth anniversary of the foundation of Northern Ireland, so this was the obvious flag to fly.

We tramped through the local village and came to a stop at the main road to Belfast. SUVs lumbered by, and while waiting for them to pass, I noticed something stuck to the nearby Give Way sign which hadn’t been there the day before.

It was the reproduction of a poster that circulated in Ireland in 1912. Back then, it had seemed that Home Rule would deliver a parliament in Dublin with an inbuilt Catholic majority; this would have robbed Protestants, Unionists, and Loyalists – most of whom were concentrated in Ulster – of their British identity and connection. Now, in 2021, Irish domination was back, along with the loss of British identity and connection for Protestants, Unionists, and Loyalists. This time, though, it wasn’t Home Rule that was the problem, but the Northern Ireland Protocol, agreed to by the United Kingdom because of its departure from the European Union. In order to avoid a hard border on the island of Ireland, in January the United Kingdom established a de facto trade border at the Irish Sea, and some see this as a calamity that will ultimately culminate in a united Ireland. Earlier this year, there were several nights of rioting in Derry and Belfast. The participants, none of whom I think it would be fair to say would ever accept being in a united Ireland, rioted in order to make clear their antagonism toward the Protocol (which, by separating them from Britain, will edge Northern Ireland closer to unification with the south), along with a number of other grievances. These include the way Republicans breached Covid-19 restrictions at the funeral last summer of Irish Republican Army (IRA) stalwart Bobby Storey, as well as a general perception that the Protestant, Unionist, and Loyalist communities have lost ground everywhere, while the other side – represented by Sinn Féin – has gained ground everywhere. For some in Northern Ireland the zero-sum game is still the default; as the rioters saw it, they’ve lost, the other side has won, and the only way that can be fixed is for them to win and the other side to lose. The poster on the Give Way sign was calculated to reinforce such thinking.

A 1912 anti–Home Rule poster repurposed and refashioned for 2021 as an anti–Northern Ireland Protocol poster Photograph courtesy of the author

We crossed the main road and followed the old one to Dublin, admiring a gnarled milestone marooned amid bungalows and black asphalt – the words Enniskillen and Dublin barely legible on its crumbling face – along with a lovely Church of Ireland church surrounded by clipped lawns and tidy graves. Soon we passed into the countryside of Fermanagh, rumpled like a bedspread, with low brown hills in the distance. Now and then cars went by, and as they did every driver slowed and gestured, and we acknowledged them all with a light flap of our hands. Those gestures were no more than a finger raised from the steering wheel, but the freightage of neighborliness was unmistakable. Yes, within half a mile of the poster with its incendiary message, civility abounded. But that’s Northern Ireland: everything is jammed together cheek by jowl, good and bad.

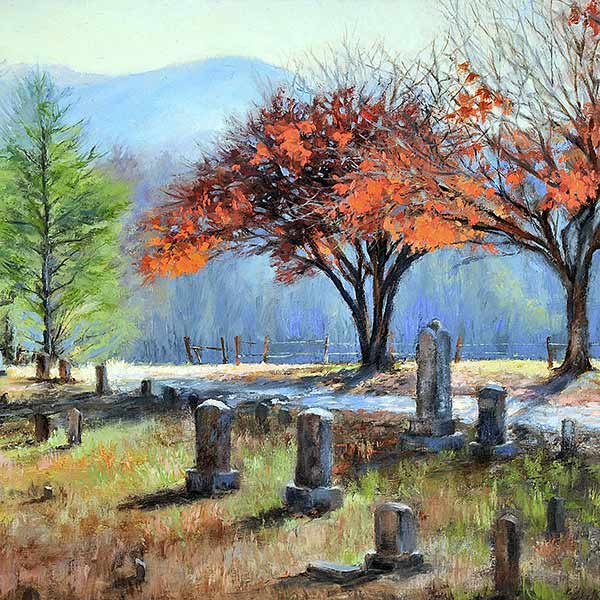

We turned into a latticework of smaller roads and strolled past spiny hedgerows and small fields rank with rushes until we came to an ancient Irish churchyard perched on a hill and surrounded by a high stone wall. Inside were half a dozen ragged Irish yew trees, a broken-down chapel, and a lumpy expanse of tottering tombstones and broken crypts. As we wandered around reading the inscriptions, one in particular caught my eye:

“Here lies the body of Redmond McManus who died in 1744 aged 76 years old …”

A quick calculation suggested that Redmond McManus was twenty-two in 1690, when William triumphed at the Boyne. The battle’s impact on Redmond would have been huge, but whether it was good or bad would have depended on which side he was on. From his name I guessed he was on the losing side, the Irish side, the Catholic side. Of course, he might have converted, which perhaps would account for his long life.

Our history is a sore tooth and the tongue keeps darting to it.

Thus I ruminated, as one does often, living here. Our history is a sore tooth and the tongue keeps darting to it. How can it not? Our past isn’t some faraway concept, full of bad things people have agreed not to argue about. On the contrary, our past is still a wound; Catholics, mostly, do not celebrate the Boyne. We like to say we did away with sides and history when the Good Friday Agreement was signed in 1998, but as the repurposed anti–Home Rule poster told me, that’s not true. Some of us are extremely committed to our side. At the moment, because of the Protocol, it’s largely the Protestant side that features in the news, but the other side hasn’t gone away. During the spring riots, the worst violence was when the so-called Peace Line was breached and youths from the two sides clashed. For the moment, rioters of both varieties are a minority, but what is the future? I don’t know the answer, but what I can say is that I’m reading the runes: the flags, the posters, the murals, the curbstones, the statements from politicians, the newspaper articles, the things I hear people saying – people I know and people I meet casually – and I am trying to work out what they mean.

We left the churchyard through a creaking metal gate, descended the hill, and walked on to the last station on our walk: a tiny, beautifully proportioned, cut-stone Georgian gate lodge that stands empty at the side of the road. We admired it and then, as we made our way home, we fantasized about buying it, doing it up, coming to it on Sundays to have tea, and maybe sleeping in it overnight. Yes, even as the runes seem to murmur ominously, we dream.

I work at Trinity College in Dublin and over the last academic year I accumulated a mound of student essays. Owing to Covid-19 restrictions, I couldn’t take them to college for shredding, so I arranged instead to burn them in a furnace on a farm.

Two days after our walk, I drove to the farm. As I turned into the yard, I spotted Peter cleaning a ditch. I know Peter well. He has mowed my lawn, cleared my gutters, unblocked my drains, and brought me firewood. I lifted my finger from the steering wheel as I drove in, and he waved in reply.

In an outbuilding, I consigned the essays to the flames while starlings flittered overhead, and when I returned to my car, I found Peter waiting to talk. We spoke of the weather, our health, and our kith and kin. Then he told me – this was his big news – that his brother had taken thirty acres. The land, he explained, belonged to a man who couldn’t farm it and so, for as long as their agreement ran, it would be his brother’s land. Here, he could put out his cattle or sheep, cut the grass for hay or silage, or use it to feed his own stock. This being such a novel development in his brother’s life, Peter had just been to walk the fields.

“What’s your brother paying?” I asked. “Is he getting a good rate?”

Peter looked at me and shook his head, delight on his face.

“Oh no,” he said. “The brother has the fields for free.”

“For free?”

“As long as he tops the rushes and maintains the hedges and the gates, they’re his for nothing.”

I’d never heard of anything like this before. Astounded, I pressed him: had the brother really got these fields for nothing?

Yes, he had, Peter assured me, and then he became positively loquacious. The fields, I should understand, were up the mountain. It was wild and lonely up there as everyone had left. All the houses were empty. And with no one left to farm, his brother was doing the man a favor. The arrangements were interesting, but not as interesting as the abandoned dwellings Peter had mentioned.

County Fermanagh Image from Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

“Are all the houses empty up there?” I asked.

“Yes, they’re all empty.”

I mentioned the gate lodge my wife and I had admired and asked if there was anything like it up the mountain.

“To be sure,” said Peter.

“Which way would I go if I wanted to find your brother’s fields?” I asked. “And see these houses?”

Peter named a local town. I was to go to the corner where Vernon Crowther was murdered and turn there. [Author’s note: Vernon Crowther is a pseudonym.] In Northern Ireland it is not uncommon for places to be identified by a violent or catastrophic incident. It could be something from the distant past, but equally it could be something that occurred during the Troubles, which ran from 1968–98. This particular incident had taken place then, when the IRA had attacked and killed two members of the Royal Ulster Constabulary – one of whom was Vernon Crowther – when he and a colleage were on duty and out in a car.

“Do you know the corner I mean?” Peter asked.

Of course I did. In a place like this, you know these things. Our landscape is shaped by such places.

“And did you know him?” Peter asked.

“Not personally, only by name.”

“Nice fellow,” said Peter. “Vernon’s farm was beside our farm. He and my father did no end of business. In and out of our house every day of the week he was. One time he was there and I had this old gun and I said, ‘Vernon, I can’t hit a thing with it!’ He took the gun and, quick as you’d blink, didn’t he drop a crow? ‘Nothing wrong with this gun,’ he said, handing it back, ‘it’s you that’s wrong, young Peter.’ Being a policeman, he knew his way around guns, and I didn’t; that’s what he meant.”

An old milestone on what was the coach road from Enniskillen to Dublin Photograph courtesy of the author

Peter then proceeded through the murdered policeman’s entire dynasty, reeling off who had died when, and of what, until he came back to Vernon, shot dead in a car at the corner where I was to turn for the road to the mountain.

“I didn’t go to his funeral,” Peter continued. “You know …” He paused. “On account of my religion. I didn’t want to cause botheration.”

A woodpecker started in a tree behind. The noise was uncanny. Peter put his hands in his pockets. He’d told me something important and now wanted the weight of what he’d said to settle in. Funerals matter in Ireland, which was why the Bobby Storey incident was so incendiary. But Peter hadn’t attended Vernon’s funeral because he was anxious that if he, a Catholic, went to the funeral of a Protestant policeman murdered by the IRA, the other mourners might have taken offense or been upset. They might have assumed that because he was a Catholic, he supported the IRA. They might even have thought that he was there to record the car registration numbers of the other mourners, many of them also policemen, with the intention of passing these details on to the IRA so it could murder them, too.

When enough time had passed, Peter said, “I did want to go, and I should have gone, but I couldn’t. Do you understand?”

Oh, I did. But as I stood there with the woodpecker hammering behind, I wondered what a stranger would make of our conversation and his disquiet. First, there was that odd segue from directions to tumble-down houses to funeral protocol if you’re a Catholic and the deceased is a policeman. I didn’t find that turn in the conversation the least bit odd. I’d experienced such turns from the ordinary to the extraordinary before. But how would someone who hadn’t had that experience find this turn? Wouldn’t they find it odd? And then there was Peter’s confession. It had been his duty, he had implied, to attend his neighbor’s funeral. But he had violated his sacred obligation in the hope of being tactful, and it troubled him still because his decision was seemingly also wrong.

Anti–Irish Sea Border graffiti on the Donegal Road in south Belfast, Northern Ireland Jonathan Porter / Alamy Stock Photo

I said goodbye to Peter and drove home. It had been sunny, but now the clouds had darkened. From the door of my study I surveyed the sky and thought about Peter’s attempt at tact, and, because it was so singularly without tact, the repurposed 1912 poster. To the naysayers who would do away with the Protocol, like the maker of that poster, Peter is on “the other side.” Though his Catholic confession codes him as Irish and maybe a supporter of a United Ireland, his funeral story suggests he’s much more complicated than the label allows. But that’s the way it goes. Our ancient rancor, and the divisions it insists upon, are still as alive in 2021 as they were in 1912. Fortunately, though, our ancient capacity for charity – practiced by both traditions – is still intact, which is what I tell people when they ask why I still live here.

A few moments later, it began to hail, the stones coming down hard and heavy. I abandoned thought and gave myself up to the pleasure of watching the green fields turn totally white. The Irish flag – a divisive symbol – has three panels: green for one side, orange for the other, and a white panel between the two, the symbol of peace. In my imagined future, the Irish flag would have no panels. It would be all white. White is my favorite color. Most people think I’m a lunatic for thinking things like this but, frankly, I don’t give a damn.

Postscript: Since I finished the piece above, placards have gone up saying the village “will NEVER accept a border in the Irish Sea!”