Subtotal: $

Checkout-

I Begin with a Little Girl’s Hair

-

Kochel: Waterfall I

-

Covering the Cover

-

Anabaptist Readings on Community of Goods

-

The Economics of Love

-

Readers Respond: Issue 21

-

Family and Friends Issue 21

-

The Bronx Agrarian

-

The McDonald's Test

-

What Lies Beyond Capitalism?

-

The Interim God

-

Robin Hood Economics

-

Is Christian Business an Oxymoron?

-

Not So Simple

-

Comrade Ruskin

-

What Are the Heart’s Necessities?

-

Exposed

-

Who Owns a River?

-

Editors Picks Issue 21

-

Working Girls

-

Was Martin Luther King a Socialist?

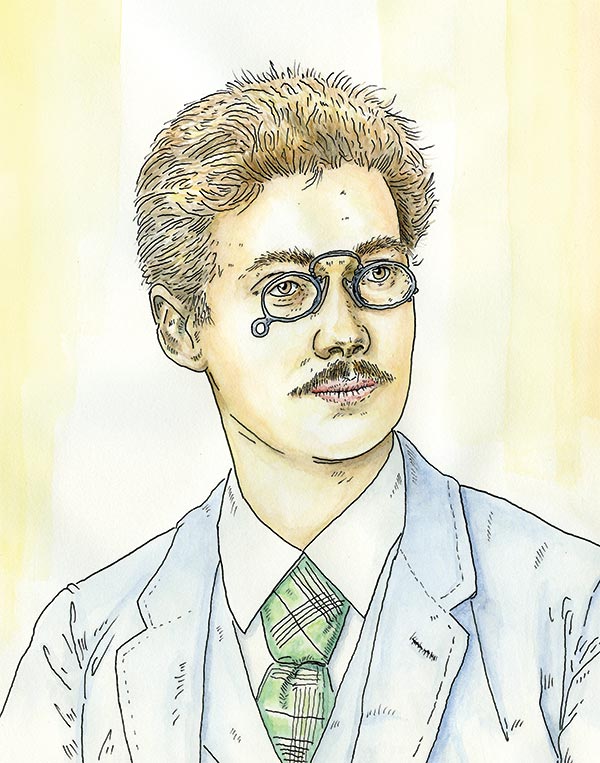

On May 1, 1919, in the tumultuous aftermath of Germany’s defeat in World War I, reactionary paramilitaries retook Munich from a group of Communists who had seized the city. They arrested a forty-nine-year-old journalist who had served as minister of culture in Munich’s short-lived revolutionary government. The following morning, amid cries of “Dirty Bolshie,” they beat him, shot him, and trampled him until he was dead.

Despite the soldiers’ words, Gustav Landauer was no Bolshevik. The year before, he had written that the Bolsheviks were “working for a military regime which will be more horrible than anything the world has ever seen.” He was something altogether different: a nonviolent anarchist who believed that the only solution to the problems of militarized, capitalistic Europe was life in voluntary communities bound together by shared work, by love, and by something else towards which he reached. For Landauer, the term “socialism” meant “a struggle for beauty, greatness, richness of peoples” (For Socialism, 1911). Far from a state system imposed by force, it was to be an organic grassroots movement that would emerge as people began to live differently, “building the new world in the shell of the old.”

Landauer was born to a middle-class Jewish family in Karlsruhe, Germany, on April 7, 1870. His generation drank deeply from the wells of German romanticism, seeking to find, in that movement’s focus on the inner life, a political corrective to factories and slums and the bourgeois superficiality around them.

“The transfor-

mation of society can come only in love, in work, and in stillness.” Gustav Landauer

After college, Landauer was swept up in the cultural and political life of 1890s Berlin. He joined a theater troupe and married an actress, Grete Leuschner (they would later divorce). He also began developing the ideas that would define his philosophy: workers needed to voluntarily abandon the capitalist system and form autonomous communities. It was a vision that he repeatedly tried to live out. Upon being released from his first prison term – to which he was sentenced for his writings in Der Sozialist – he joined the communitarian effort Neue Gemeinschaft. Here he met the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber, who became a lifelong friend. A period of relative calm followed, during which he worked on translations of Shakespeare and Meister Eckhart.

Jason Lansel, Gustav Landauer

Although an atheist, Landauer had long admired the figure of Christ, and wrote in Call to Socialism that “Jesus was a truly inexhaustible figure…. Where would our whole … machinery be without this calm, tranquil, suffering great One on the Cross of mankind!” Through Buber, he began to see in Judaism as well the outlines of a power that would draw mankind together in a coming messianic age. The Hasidic legends he learned, explained the philosopher Michael Löwy in his 1992 study Redemption and Utopia: Libertarian Judaism in Central Europe, represented to Landauer “the future within the present, the spirit within history, the whole within the individual… The liberating and unifying God within imprisoned and lacerated man; the heavenly within the earthly.”

In 1908, his period of calm at an end, he helped to found the Sozialistische Bund, a federation of cooperative communities. In 1911 he published For Socialism, the clearest and most complete statement of his thought: “Socialism has nothing to do with demanding and waiting; socialism means doing.”

“Jesus was a truly inexhaustible figure – so rich, so bountiful and generous.” Gustav Landauer

The coming of World War I brought an end to the Bund’s activities but, even during wartime, Landauer encouraged Germans to live out productive cooperation: to grow food on the borders of streets and on lawns – projects which would be schools of community. With the armistice, an explosion of interest in social change rocked Germany – interest in Landauer’s anarchism, and in the bloodier game of Communist revolution. The Marxists, he wrote in a 1910 book review, “have accustomed themselves to living with concepts, no longer with men. There are two fixed, separate classes for them, who stand opposed to each other as enemies; they don’t kill men, but the concept of exploiters….”

Such violence had never been Landauer’s way. “There can only be a more human future,” he once insisted, “if there is a more humane present.” But he was swept up in the government’s crackdown on anything that smacked of dissidence. After his murder, one of his daughters found his body dumped in a common grave.

But his physical death did not kill his legacy; his influence only grew. Landauer’s vision of a federated network of agrarian communities was the blueprint for Israel’s kibbutzim; his ideas profoundly shaped the thought of Bruderhof founder Eberhard Arnold, prompting him in 1920 to start a community inspired in large part by Landauer’s ideals.

“What have we made of our younger generation?” Landauer asked in his 1911 call to action:

… cowardly little men without youth, wildness, courage, without joy in attempting anything…. But we need all that. We need attempts…. We need failures upon failures and the tough nature that is frightened by nothing, that holds firm and endures and starts over and over again until it succeeds, until we are through, until we are unconquerable. Whoever does not take upon himself the danger of defeat, of loneliness, of setbacks, will never attain victory…. We want to create from the heart, and then we want, if must be, to suffer shipwreck and bear defeat until we have the victory and land is sighted.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.