Subtotal: $

Checkout-

From Mourning to Praise

-

Did the Early Christians Understand Jesus?

-

Hope in the Void

-

Insight: Loving Your Neighbor

-

Insight: Caring for a Neighbor’s Soul

-

Insight: Evangelism vs. Neighbor-Love

-

Needing My Neighbor

-

The Coming of the King

-

Poem: No One Wrings the Air Dry

-

Does Faith Breed Violence?

-

Editors’ Picks Issue 8

-

The Danger of Prayer

-

Eberhard Arnold: an Appreciation

-

Gripped by the Infinite

-

Janusz Korczak

-

Dead Men Live

-

Mondays with Mister God

-

Who Is My Neighbor?

-

Urban Mansions

-

Readers Respond: Issue 8

-

Family and Friends Issue 8

-

Love in Syria

-

Invisible People: Why I Make Portraits of San Diego’s Homeless

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Can broken relationships be restored – even two decades after the genocide?

Twenty-nine-year-old Denise Uwimana, a Tutsi, was housing seven relatives and friends along with her two sons, aged four and one-and-a-half. Nine months pregnant, she expected her baby’s arrival any day. Her husband, Charles, was working some thirty-five miles away. On the afternoon of April 16, 1994, militants broke into her home and attacked five inhabitants, leaving them to bleed to death. Remarkably, Denise and her children were spared. Several hours later she went into labor and delivered her third son.

Denise and her sons survived the genocide against immense odds. Many of her relatives, though, were killed. So was her husband – she still does not know how or when his death occurred.

In spite of this loss, Denise chose to forgive the perpetrators of the genocide and work for reconciliation in her country. She later married Wolfgang Reinhardt, a German theologian and aid coordinator, and founded Iriba Shalom International, a nonprofit organization that provides spiritual and material support to genocide survivors.

Plough: Denise, choosing the way of reconciliation after what you experienced must have been difficult. Was there anything in your upbringing that prepared you for this?

Denise Uwimana: I was born into a Christian refugee family. In 1962, my parents fled from Rwanda to Burundi, and later to what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, because of political unrest caused by radical Hutus who wanted to kill Tutsis. I grew up mostly in the Congo.

As a family, we had a special and treasured tradition: after dinner each night, we would meet and discuss all we had experienced that day. We sang worship songs, my father read a Bible story, and we talked about any misunderstandings that had arisen between us during the day. We forgave one another, exchanged prayer requests, and prayed together. Every morning we children woke up early and ran to our parents’ bedroom, where we knelt before their bed, prayed together, and got their blessing for the day.

My parents gave us a solid education in the Christian faith. In my adolescence, I knew what sin was and how to protect myself so as to not be involved in things contrary to my beliefs.

We had a neighbor who loved me and the other village children very much. One day, she became ill with meningitis and was taken to the hospital, where she died one week later. We children were very shocked and cried many tears for her. I started thinking more about the end of life, asking myself where I would go if I would die. While mourning for her, we started meeting in her house for prayer. This prayer meeting grew, and we started confessing our sins and seeking Jesus. It was a kind of revival. Our pastor observed that the number of youth and children meeting together was growing and assigned a church elder to care for us.

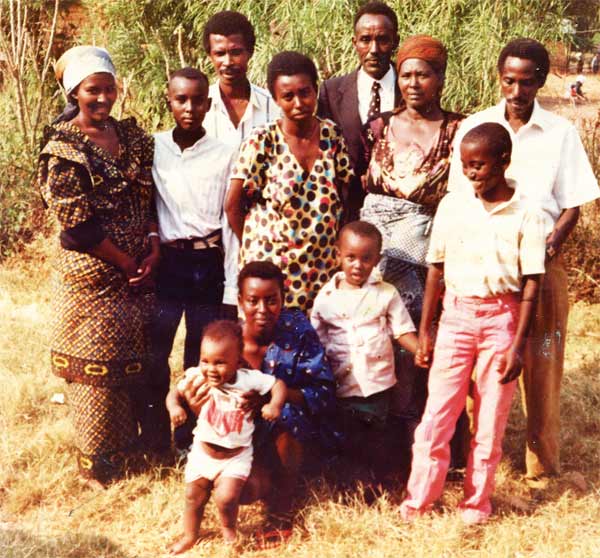

Denise, (left) and Charles, (back row third from left) visiting Denise’s parents in the Congo in August 1993. This is the only photo Denise has showing her, Charles, and their two young sons (front row).

Had you faced discrimination as a Tutsi before the genocide?

When I was twenty-one years old, friends invited me to visit them in Bugarama, a town in southwest Rwanda. They hoped to help me find a job at CIMERWA, a large cement-manufacturing plant there.

One day, I was walking along the road when the prefect (préfet) of the regional authority drove by in his white pickup. He stopped his car and arrested me on the pretext that I didn’t have the correct papers. When he searched my handbag and found a photograph of a friend who had invited me to apply for a job at CIMERWA, he accused me of coming to spy on the company. He took me to the mayor, hoping to convince him to send me to a nearby prison, but he would not.

Dissatisfied, the prefect then took me to an immigration office near the border. He told the Rwandan officials there that I was a refugee Tutsi from the Congo seeking employment in Rwanda. He knew that I had become friends with Charles, the man I later married, and he knew that Charles was helping me find a job at CIMERWA. After some discussion, they decided not to send me to prison but instead to fine me and expel me from Rwanda. On the receipt for the fine, the prefect stated the official reason for my punishment was that I was inzererezi, a Rwandan term for a vagrant woman or lowlife. The officials heaped verbal abuse on me. The next day, the prefect followed me to the Congo border crossing. “You will never get a job in Rwanda. There is no chance for Tutsis in Rwanda,” he shouted after me.

This experience made me hate Rwanda. I did not want to hear anything more about the country. If my housemate tuned the radio to Rwandan news or music, I turned it off. Every time I looked at the receipt for the fine, I got into a rage, and fear and hatred toward Hutus rose up in my heart. I suffered from nightmares. My family realized that I was deeply affected. “That evil man, the prefect, broke her heart,” they said.

I kept praying that God would heal my wounds and help me to forgive. One day, as I was staring yet again at the receipt from the prefect, an inner voice seemed to say, “As long as you keep that piece of paper, you will never forgive him. You should get rid of it.” I tore up the receipt and forgave the prefect and the immigration officials. After some months, I got a letter from friends in Rwanda telling me that the prefect regretted his unjust behavior toward me, admitted I was innocent, and asked them to find me and apologize on his behalf. He even met Charles and reconciled with him. In the end, I did get a job with CIMERWA and moved back to Rwanda.

In the months before April 1994, were there warning signs that something like the genocide might be coming?

As has occurred before other genocides, the media carried out a contemptuous propaganda campaign. Already in 1990, the Kangura newspaper published “The Ten Commandments of the Hutu” which denounced every Hutu who married a Tutsi woman as a traitor, branded Tutsis as being dishonest in business dealings, demanded Hutu dominance of higher education, and required that only Hutus should hold strategically important offices or serve in the Rwandan armed forces. Most inhuman was the eighth of these commandments, which stated, “Hutus must cease to have pity for the Tutsi.” The radio station RTLM incessantly broadcasted the message that Tutsis are cockroaches and snakes; this station later orchestrated the massacres. Once a group of people is dehumanized in this way, it becomes easy to kill them.

Rwanda is the African country with the largest percentage of Christians. How does that fact square with genocide?

Long before the genocide, Rwanda’s church leaders were mostly silent toward or supportive of the ideology of Hutu superiority. Members of all churches spread divisive propaganda and were even actively involved in the killings. When a cardinal from Rome visited Rwanda, he asked the church leaders he was meeting with, “Are you saying that the blood of tribalism is deeper than the waters of baptism?” One leader answered, “Yes it is.”

Sadly, Christian education in Rwanda did not teach a mature and critical attitude to government based on the standards of the gospel, but rather emphasized blind obedience toward those in power. Whatever the leaders in power commanded was supposed to be carried out. There was no tradition of Christian resistance, even if the powers of state and church demanded something completely contrary to the will of God as shown in the Bible.

Villagers, both Tutsi and Hutu, gather to celebrate at the building site of Iriba Shalom International’s community center in Mukoma (2015).

Villagers, both Tutsi and Hutu, gather to celebrate at the building site of Iriba Shalom International’s community center in Mukoma (2015).

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Luitpolt and Josephine

In your own Pentecostal denomination, several members committed crimes during the genocide. What was your response?

I was disappointed in my church, and very angry. This issue has not gone away. Just recently, in early January 2016, we heard about a pastor from our church who was sentenced to life in prison because of his involvement in the killings.

Despite this, in the months after the genocide, an inner voice told me, “The devil is everywhere. Stay here in this church. Help this people to change. You will be a light for them.” After the genocide, many left their churches, but I stayed in mine and am still a member today.

In 1994, did you know any Hutu Christians who stood up for you?

Yes, an exceptional Hutu couple, Luitpolt and Josephine, showed me what it means to love your neighbor in a time of genocide. Luitpolt worked as a car mechanic at CIMERWA, the factory where I was also employed. He met me secretly almost every day to pass on messages of encouragement: “Stay strong.” “Do not be afraid.” “We stand with you.”

Luitpolt told me that because he had found the cross, he never wanted to betray Jesus again.

Josephine took my baby son to the clinic for his vaccinations because it was too dangerous for me to go. On the way, she came to a militia checkpoint. She said, “I am not prepared to let this child be killed. If you want to kill him, first kill me.” She was pregnant at that time and later gave birth to a baby girl whom she named Sauvée, or Rescued One.

After the genocide, I was able to meet with them and ask why they were willing to die while other Hutus were proud to exterminate Tutsis. Luitpolt told me that once soldiers had grabbed him and pushed him on the ground to kill him. He had told them, “I am ready to die. Tutsis whom you kill are also human beings and bleed like me.” He was not a pastor or a priest; he was not a church leader. But he told me that because he had been saved and found the cross, he never wanted to betray Jesus again. That is why he and Josephine did what they could and suffered with me in my darkest hours.

After 1994, you started visiting former neighbors regardless of their ethnic classification. How did that come about?

When I came back to my village after the genocide, some residents welcomed me, but most kept a distance. Of course, I was deeply wounded inside. I had no hope and didn’t care about keeping up friendships. I would just attend church and then come straight home.

Before the genocide, though, I had been visiting poor and sick people on behalf of my church, bringing them food and encouragement. After I came back to my village, I gradually began doing this again. My visits seemed like a miracle to my neighbors because they saw that I made the first move. They felt guilty and thought I would never come; even if they were not actively involved, they were Hutu and I was a survivor. They would ask, “How is it that you can come to see us?”

You started a nonprofit organization, Iriba Shalom International, to help genocide survivors. What inspired this decision?

During the genocide I made a vow that if I survived, I would use my life to tell people that God exists and to encourage them to believe in him.

A few years after the genocide, I gave up my job at CIMERWA and started working for a Christian organization called Solace Ministries, because I realized there were many widows and orphans who needed help. We would visit them or gather them together to hear their stories, and we’d look for ways to help them heal and get back to normal life.

The militia member raised his sword, ready to kill my sons and me, but he did not.

One of the places I visited was Mukoma, a village in the same county as Bugarama, the town where I survived. I went there because my mother-in-law, Consoletia, lives there. While I was in Mukoma, some widows came to see me and told me their stories. On April 14, 1994, a group of murderers who had already killed these women’s husbands and older sons forced them to bring their baby boys as well. The women had to lay their babies on a big log, where the killers cut off each baby’s head with a machete.

These women’s plight touched me very deeply. Mukoma hadn’t received any help because it was so remote; our organization usually only worked in cities or larger towns. But when I heard their story, I realized that it was connected to my own.

After the birth of my third son on April 17, 1994, I had been taken to CIMERWA’s small clinic. Shortly after I arrived, a man had walked in bragging, “Do you know what we did in Mukoma? We killed all their boys!” Now I suddenly realized that this murderer had first been in Mukoma and then had come to the clinic intending to do the same to us. He raised his sword, ready to kill my sons and me, but he did not. This miracle was one of the reasons I founded Iriba Shalom, which is based in Mukoma.

One of Iriba Shalom’s programs aims to connect survivors with sponsors in Western countries. It’s helpful for survivors to know that there are people in the wider world who care about them and their stories. Iriba Shalom is also in the process of building a community center in Mukoma to provide a safe location for trauma counseling, fellowship, medical assistance, and practical help related to finances and the daily challenges of widows’ lives.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Denise, (right) visiting the home of a genocide widow in Mukoma to hear her story.

Is Rwanda as a country finding healing from its past?

Reconciliation is the official policy in Rwanda today. It is a good policy, but obviously reconciliation cannot simply be ordered from above. It is always a miracle when somebody can forgive those who tortured and killed his or her loved ones. In Rwanda this miracle is happening on such a great scale that even secular observers are astonished. As a friend of mine said, “We cannot overestimate the power of the cross in reconciliation.”

Truth and confession are important to the healing process. Not all churches have publicly confessed their involvement in the genocide. But many have, and are now playing an active role in the healing of society. According to Professor Vincent Sezibera, a leading Rwandan trauma expert, the most effective healing from trauma happens in a community-based approach as in the fellowship of Iriba Shalom. When survivors help each other – when they pray, sing, dance, eat, and work together in a loving community – they feel a new sense of purpose and dignity. The same is true when they receive support through sponsorship or a local “alternative family,” and when they learn how to generate an income.

We’ve seen several examples of survivors now working together with those who murdered their neighbors or family members. At an Iriba Shalom event, one woman said of the young killer of her children, “He’s like my son now.” He added, “She is my mother, and I help her as much as I can.”

Interview by Erna Albertz for Plough on January 12, 2016.

All images courtesy of Denise Uwimana.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

metin erdem

Yes there is a country in Africa called Rwanda. May be most of us will not find its place on map. But there was a genocide of the anniversary. Over one million people killed. We all watched it on the TV. It was more than civil war. We need to thank to those people who tried to do something for the peace of the people in Rwanda. We could do more; teaching people the God and his orders. Killing a person is killing the all humanity and love one another . We need to learn to walk together in brotherhood. Thanks again to the those volunteers for helping peace in Rwanda.