Subtotal: $

Checkout-

The Quest for Home

-

In Search of Lost Fig Trees

-

Child of the Stars

-

Refugee Letters

-

Life in Zion

-

How to Run a Cemetery

-

Integrity and the Future of the Church

-

Daring to Follow the Call

-

Poem: “For the Celts”

-

Poem: “Wreathmaking”

-

Poem: “The Hunger Winter, 1944–5”

-

Editors’ Picks: The Cult of Smart

-

Editors’ Picks: The Utopians

-

Editors’ Picks: The Lincoln Highway

-

Casa de Paz

-

The Pilsdon Community

-

Letters from Readers

-

Nonexistence Does Not Scare Me

-

Toyohiko Kagawa

-

Covering the Cover: Beyond Borders

-

Choosing America

-

Church as Sanctuary and Shelter

-

Northern Ireland’s New Troubles

-

When Migrants Come Knocking

-

The Florentine Option

-

Three Kants and a Thousand Skulls

-

The End of Rage

-

Telling a Tale of Two Fathers (Video)

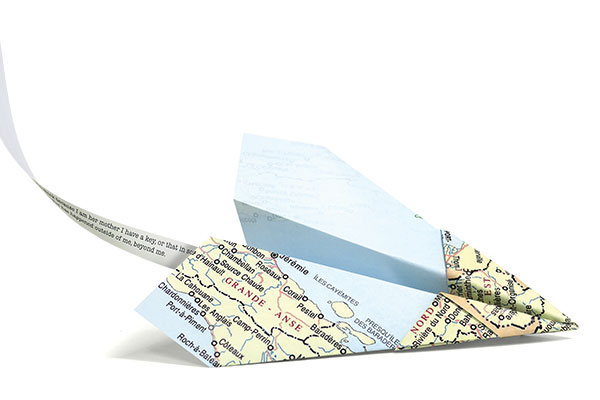

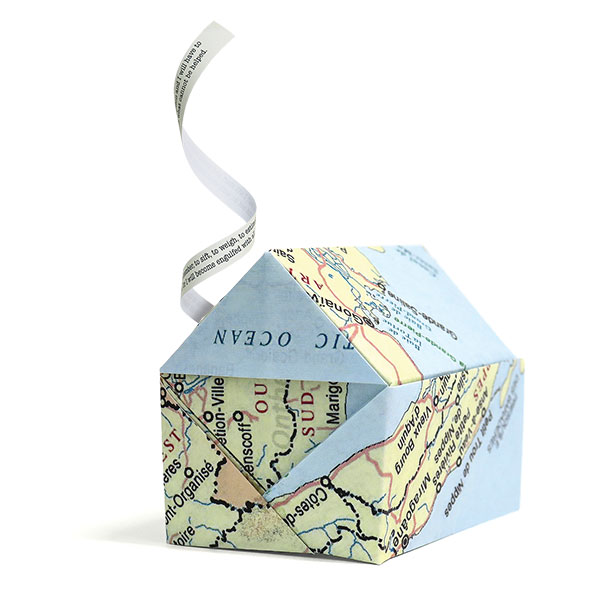

Home Is Not Just a Place

With words we build homes no separation can take away.

By Edwidge Danticat

September 16, 2021

My fifteen-year-old daughter, Mira, is taking a summer writing class online. Taught by the writer Erica Cardwell, the class is called “Writing the Self.” Mira and I are both won over by the course description:

Imagine: “The Essay” is a body of water – far-flung and teeming into the distance. And you, the writer, are alone on shore. Will you enter the water? And if so, how will you swim? Or will you stand on shore as the water splashes against your ankles?

“I wish I could take this class,” I tell Mira.

What I mean is I wish I could have taken this class when I was her age. I have read most of the assigned essays. I decide to revisit some, which I read out aloud to Mira. We read “When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Re-Vision” (1972) by the poet Adrienne Rich. I have been looking for something more concrete than my own enthusiasm to convince Mira that this class is an incredible gift, especially in the midst of a global pandemic and racial justice protests, at a time when we are all, writers and non-writers alike, searching for the right words to describe our unique personal state, as well as the overall human condition. Then I come across Adrienne Rich’s description: “Writing is re-naming.”

We then read Audre Lorde’s “Poetry Is Not a Luxury” (1977), where Lorde reminds us, “There are no new pains. We have felt them all already.”

In an August 1979 exchange between the two women, Lorde cites her choral poem about the frequent silence around the lives and deaths of murdered Black women and girls:

“Need: A Chorale for Black Woman Voices”

How much of this truth can I bear

to see

and still live unblinded?

How much of this pain can I use?

Reading this, I think, writing is also home, a sometimes-broken home that we are trying to put back together again, but still a home nonetheless.

Every time Mira finds herself in a new situation, I can’t help but remember when she was eleven years old at a friend’s birthday party, where she tried to sit next to another girl. The girl turned to her and shouted very loudly “No!” Mira limped over to where I was sitting, looking heartbroken. My reaction in that moment was cowardly. I put my arms around her and asked if she wanted to go home. Thankfully, she wanted to stay. Eventually Mira found some other friends and enjoyed herself. At the end of the party, the birthday girl’s parents lit some sky lanterns that were supposed to float above the bay behind their home and glide away from the shore, towards the sunset. Thick, gloomy clouds blocked the sunset and most of the lanterns turned to ash, never leaving the ground. Had we left the party, Mira might have learned that someone’s rudeness can send you running home. She also would have missed out on an opportunity to discover, or rediscover, that though home can be a safe place, we shouldn’t always rush there.

When I ask Mira what she’s writing for Ms. Cardwell’s class, she demurs, then tells me that her first piece is about a tree she and her friends used to love to sit under during recess in elementary school.

“The same tree where a boy hit you in the forehead with a rock?” I ask.

“I’m not going to write about that,” she says.

She will be writing about digging for worms under that tree with her girlfriends, she says, most of whom now go to different schools, and have different friends. Like all of her writing, I won’t be allowed to read it. This has been our rule since even elementary school. Writing is her home too.

We are all, writers and non-writers alike, searching for the right words to describe our unique personal state, as well as the overall human condition.

Once while driving Mira home from that same school, we were listening to an audio version of Tillie Olsen’s “I Stand Here Ironing” (1956), a short story about a mother discussing her troubled teenage daughter on the phone. I can never revisit that story without thinking of my Haitian mother and all the ironing she did in her bedroom on Sunday nights, first in our crowded two-room apartment in Port-au-Prince, and later in the two-bedroom apartment my parents rented in East Flatbush and the house they later bought in that part of Brooklyn. When Olsen’s character speaks of having to send her daughter away, first to family members, then to a girls’ group home, and of the daughter’s ensuing separation anxiety, I always feel a lump in my throat. In the car with Mira that day was the first time I was hearing that story as a mother, and in the presence of one of my two daughters.

At the end of the story, I turned to look at Mira in the back seat, and tears were streaming down her face. Overeager and excited, and still being a writer, I asked Mira what exactly about the story was making her cry. Which part moved her? Was it the daughter not being able to keep her mother’s letters, or any other personal possessions, with her in the group home? Or was it the final line of the story where the mother wants her daughter to know that the daughter is “more than this dress on the ironing-board, helpless before the iron”?

After I pushed a bit too much, Mira answered, “I think I cried because you were crying.”

Midway through the essay class, while going through a box of old things, I find a wooden machete my mother gave me a few years before she died, a memento she’d bought on a Caribbean cruise. I tell Mira that I am writing about my mother’s wooden machete. I tell her that I see the machete as a symbol of the kind of strength that will help us all survive these challenging times. I am also writing about the time when Mira was six years old and we took my mother to the airport so she could return to her home in Brooklyn, after a visit with us in Miami. Taking my mother to the airport and watching her leave always reminded me of my first concrete childhood memory, which was of being peeled off my mother’s body on the day she left Haiti for the United States when I was four years old, leaving me in the care of my aunt and uncle in Port-au-Prince for eight years.

That day as Mira and I watched my mother merge into the crowd heading towards her gate at the Miami airport, Mira screamed “Manman!” at the top of her voice. My mother turned around and stared at us. She seemed relieved that there was nothing wrong with either Mira or me. As other travelers were dashing around her, my mother took a few steps in our direction, then stopped. She seemed to want to walk back to us, but knew she could not. Coming back to us would mean just postponing another goodbye. Her life, at that time, was in New York, as were her house, her friends, and her church. Her flight was already boarding. She slowly raised the hand that had been resting on her carry-on bag and waved once more, then she turned around and continued walking to her gate.

Stories will remain our transit points, our shorelines, and our home.

I ask Mira if she remembers what happened that day. She remembers us taking my mother to the airport a bunch of times, she says, but does not remember ever calling after her. But she does recall another moment at the same place. Once, while my family and I were waiting to board a flight to New York with my mother, my mother went to look for a restroom and accidentally walked past security, leaving the boarding area without her boarding pass or her cell phone. When our plane began boarding, Mira and I went looking for her and found her pleading, in her somewhat hesitant English, with an impatient TSA officer to let her back in, or at least to accompany her to the gate, and to us.

“She looked so lost and so scared,” Mira remembers. “Like she thought she’d never see us again.”

I had also feared that we might never see my mother again, or that she might end up on the wrong flight to some distant country, or as an eternal ghost in the airport, passing everyone by. The words my mother would later use to recount to her friends the experience of being lost in the airport now trickle back into my mind. They still sound like the elevator pitch of a much more elaborate four-act tale:

M pèdi. Yo jwenn mwen. Vwayaj la kontinye.

Nou rive lakay.

I am lost. They find me. The journey

continues. We arrive home.

“Perhaps home is not a place but simply an irrevocable condition,” James Baldwin wrote in his 1956 novel Giovanni’s Room. Recalling my mother’s words, and imagining my daughter’s, I know that we have all built a kind of home that no physical separation can take away. In the beginning was the Word, after all, as I suspect it shall also be in the end: stories will remain our transit points, our shorelines, and our home.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.