Mark is gone. The news wasn’t a shock; I had known it was pending. But that didn’t soften the impact for me or for thousands of other Americans: North, South, and Central Americans alike.

Mark Zwick passed away in his home in Houston, Texas, on Friday, November 18, 2016. His legacy? Casa Juan Diego, the gospel in action on the front lines of the border crisis.

Mark was a Catholic from Ohio with guts, faith, and a calling from God. With his wife, Louise, he founded Casa Juan Diego, a Catholic Worker house of hospitality for refugees in the heart of Houston.

Thirty-six years later, Mark leaves Casa more than a city block in size, a well-known refuge for recent arrivals to the United States. No matter their origin, Casa welcomes them with hospitality, food, clothing, medical care, and a haven of community, offered at no cost. Casa’s approach is personal and uncomplicated by bureaucracy, inspired by Catholic Worker founders Peter Maurin and Dorothy Day.

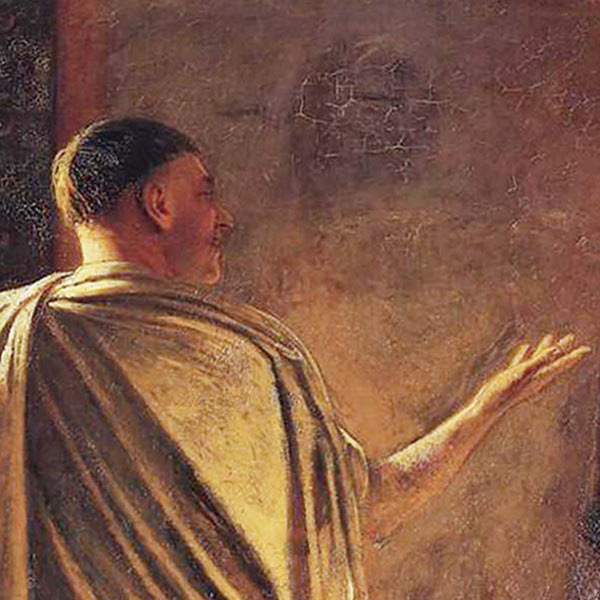

Mark and Louise Zwick

Aside from the hundreds assisted at the door weekly, more than one hundred thousand immigrants have been sheltered within Casa, a drama I wrote about while working there in 2015.

I left Casa a few months ago, having worked there for twelve months as a full-time volunteer. Mark was already failing when I arrived, weakened by recently diagnosed Parkinson’s disease. Louise had shouldered the main practical load for him, and continues to do so today. Nonetheless, Mark’s touch and influence are tangibly present. Casa stands as his vision, vessel, and vocation. Every aspect reflects his sage humility and gentle character.

That doesn’t make it serene, though. Life at Casa is messy and real. The Zwicks often quoted Dostoevsky’s famous line to us when scenarios got tough: “Love in action is a harsh and dreadful thing compared to love in dreams.” As Mark writes in his book Mercy Without Borders:

Our work is unlovely.… Things can go so wrong. The problems are so serious, with trained and committed people so few and good resources so rare, that our work is a constant challenge and sometimes we go from one crisis to another. Hospitality is the hardest thing we do. Babies are born around the clock. People have to find a place to move to. [Sometimes] those who come for help are refused because we cannot or do not offer it… True, if we can’t stand the heat, we should move out of the kitchen. Fortunately, the heat of God’s love and that of the immigrants can counteract any pain.

Mark, his idealism stripped away decades ago, was centered on something far more substantive than results or dreams:

Sometimes we feel that we wouldn’t do this work for any amount of money. It helps that we give our work as a gift, but the work itself brings us to our knees. It seems that the Lord wants us to be broken like our guests, to realize that the seed and the Spirit bloom only in ploughed, cultivated, and broken soil, not in the hard, smooth ground. Only faith can underwrite this work day after day, night after night, year after year, with no future except today’s challenges. We don’t have much of a choice, either: go to our knees or collapse. We believe, or we die.

Mark and Louise believed. They are the starkest example of commitment I know. I doubt whether they ever took a vacation in thirty-six years.

In my single year at Casa, I encountered gravity that drove me to my knees, as often from sheer exhaustion as from focused petition. There are times when the weight of your own inadequacy pushes you down so far, you wonder if you will punch right through the bottom of your own belief, into a cold and crippling cynicism. People, yes, people in the image of God, can wring you out sometimes. Paradoxically, these same people, in all their hurt and familiar humanity, are the ones who hold you up in the end, who return your touch with a fierce and buoyant love.

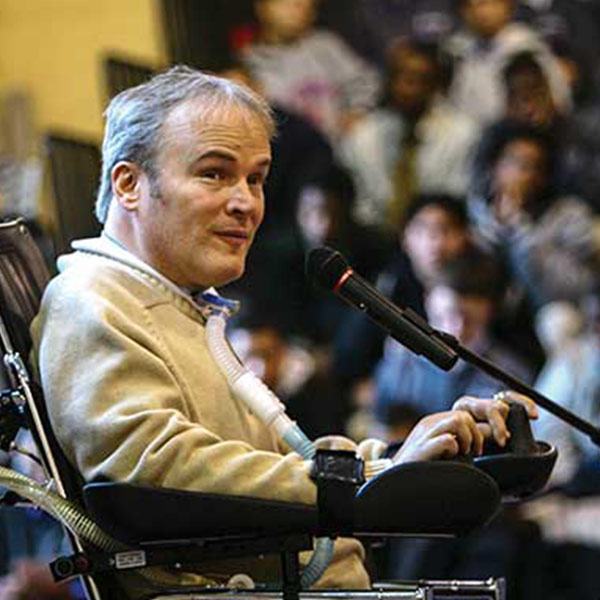

Refugees camping outside the Casa Juan Diego clinic, awaiting space in the guest houses

I know these dynamics colored the Zwicks’ lives. But Mark and Louise weren’t committed to social work. They were committed to Jesus and his demands on their lives. Such fortitude simply can’t be mustered apart from Christ. Mark would be the first to tell you that it’s never been about social work: pampering the needy or correcting wrongs. It’s about fulfilling gospel requirements. “The scriptures are the basis of our work;” Mark writes, “we are foot washers and problem solvers rather than hand holders.”

Today, we guess at an unpredictable future. No one knows where we’ll be as a country six months from now. With caustic rhetoric from the election season still ringing in our ears, Americans are readying themselves for significant change, not least down at the border. Major upheaval in immigration policy is likely coming our way.

With all the menacing talk of walls and deportations, there’s a lot of fear. Many immigrants I know feel abandoned and trapped, and are bracing themselves for vague, pending tragedy. We who love them may already be a minority.

But look at Mark. He proves that followers of Christ are empowered beyond a simple protest of the system. We can do more than rail against the enormous powers that be: we can quietly live what we believe, regardless of trending hype and shifting politics.

For thousands of immigrants, Mark Zwick stood in the gap, a pillar of Christ’s mercy, offering shelter for their hearts as much as for their bodies. Mark believed they bore the image of Christ, no less for their lack of legal status. He knew they possessed, no less than we, the right to life and survival, something denied them south of the border.

Nearly every day of my year at Casa Juan Diego, people came to the door asking to see Mark. They brought him their affection, their gratefulness, their need, hope, and despair. “Está Don Marcos?” they always ask. Ya no, queridos amigos – no, friends, Don Marcos won’t be there for you anymore. But take heart. The mission he began and the spirit he represented live on vibrantly, both at Casa Juan Diego, which will continue to welcome you, and in the hearts of every one of us privileged to have known him. I count you my people, too, and, like Mark Zwick, I shall boldly defend you as long as I live.

Quotes from Mark Zwick are taken from his book Mercy without Borders.

A version of this article appeared on the Bruderhof Voices blog.