Subtotal: $

Checkout

Stark Perry and Me

A self-published memoir I found in a trash can helped me visualize a future for my own child with disabilities.

By Chelsea Boes

January 3, 2025

Available languages: Deutsch

“Children’s minds are fragile. They should be treated with more care than rare old glass.”

—Stark Perry, My Vapor

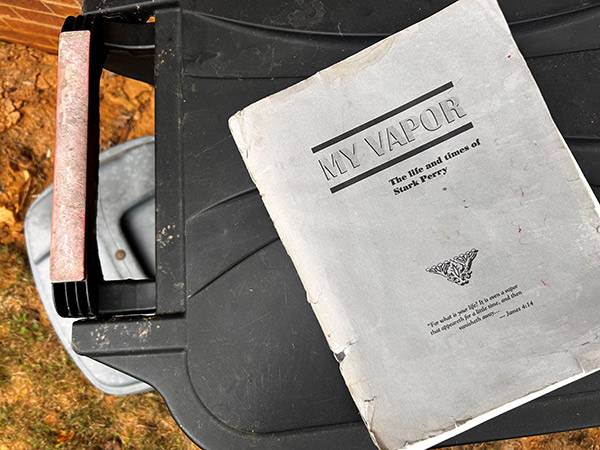

The book tumbled into my mother’s garbage can. I read the plain gray cover from above: My Vapor: The Life and Times of Stark Perry.

Fishing the volume out, I snuck it into a folder of items just for me. As my parents prepared for their big move from New York State to join my young family in North Carolina, they were pitching dead weight, chucking heaps of photos and old papers. But My Vapor I was keeping for myself.

Old people often tell me they wish they had written down their life stories. Sometimes they ask me to read manuscripts or self-published volumes, which often turn out boring because they’re built from nostalgia rather than plot and fine detail. Not My Vapor.

Stark Perry was born in 1915 after a long labor with the use of what Stark refers to as “instruments.” “To this day,” he writes, “it is difficult for me to walk, talk, and use my hands.”

I started his book on the family drive back south. Could this opening be as interesting as I thought it was? If so, the book deserved an editor. (In excerpts appearing here, I am that editor. But I’m just fixing typos.)

Stark describes a point during the 1930s when a traveling AT&T exhibition lands at the Yates County Fair in Penn Yan, New York. A presenter shows off a new wonder of engineering: a voice-recording telephone. Teenaged Stark and the presenter make small talk. Then, the marvel: the presenter plays the conversation back.

Photograph by Jonathan Boes. Used by permission.

Stark grows agitated. “Of course, I knew that I didn’t sound like other folks,” he writes. “The guy talking to the man on the tape sounded like the other cerebral palsied people that I have known. It couldn’t be me. But it was.”

Stark reasons with the reader: “A person with cerebral palsy thinks in plain words. The trouble is between the speech center and the mouth.”

I called my mom. “This book is amazing. Where did you get it?”

“It was something my dad had. I saved it from my parents’ dumpster when they were moving.”

“You’re kidding.” History was repeating.

Over the next weeks of reading, I watched the boy Stark grow into a man and grapple with his disability. He lived a small life of communal pleasures now mostly displaced by the internet – church suppers and bazaars, visits from cousins, long games of chess – all occurring in the places I had grown up.

Soon my mother called again. “I talked to Grandma about that book you found. Stark Perry was their neighbor down the street. Grandpa used to sit with Stark when his wife went out for groceries, and he was sitting there when Stark died.”

Again I said, “You’re kidding.”

So Stark was not exactly a family friend – more a family anecdote, and a nearly forgotten one at that. But the truth was, Stark was becoming my friend.

I saw Grandma at a family graduation party after I had been enjoying Stark’s company on the page for several months.

“What else can you tell me about Stark Perry?”

“You’d see him walking down the street – ” and here she put her arms out in spasms to show how he moved.

“Did he have white hair?”

She thought, rolling her snappy, bright brown eyes up toward the ceiling. “I don’t remember.”

Maybe my late grandfather would have recalled more.

Three years ago, when my best friend calmly suggested my toddler might be autistic, I cried.

Not my kid. I had not signed up for that.

“Listen,” my best friend said to me and my tears, “What if she does have it? So what if she does?”

At this time, during Covid, diagnostic waiting lists stretched months long. Yet evidence mounted. As an infant, my daughter had gazed toward other parts of the room while we talked to her, a habit that had struck a worried chord in my chest. I could mostly ignore this twinge – but then as a toddler, instead of asking for a glass of water, she’d climb to the top floor of the house to a corner room to find a half-full water glass on a nightstand. She walked early. But she talked late, and more to toys than to people.

When I picked her up from church childcare, a grizzled woman said with a martyr’s force, “We’re going to have to figure out something to do with her.”

“Oh!” I said. Because what else could I say?

“She ran away from the playground. She wouldn’t come back. She wouldn’t listen. She wouldn’t stay with me. She wouldn’t stay with the other kids.”

After, I sat in my car and sobbed mascara all over.

Stuck in the underserved chasm between “early intervention” and kindergarten, I tried to get the autism evaluation. I made calls. And more calls. And emails and texts.

“At first I appeared to be a normal baby,” Stark writes. “But, as time went on, I did not do the things that a child should be doing at the different ages. My parents became concerned.” When a neighbor child advances far faster than he, Stark’s parents drive a team of horses to chiropractors and specialists. “But there was no cure for cerebral palsy.”

Finally, when the disquiet had been clanging for months, we found ourselves in a virtual diagnostic appointment. (“Kids are usually more themselves when they’re in their own space,” the scheduler had explained, “instead of right after taking a long car ride to the office.”)

The psychologist watched my daughter play. She had me carry in a jar of chocolate chips to observe how my daughter asked for it. She did ask, but not with words. She came for it then handed it to me to open – an action the psychologist interpreted as her being “object-oriented instead of people-oriented.” This sounded like a description that I, a socially gifted extrovert, would have saved for my worst enemy.

Stark refers to his cerebral palsy as a “handicap.” Now we favor the word “disability” or even “diversity.” Autism, classified as a disability by the US Social Security Administration, is also frequently referred to as neurodiversity – an alternate but not inferior wiring of the brain. Not a pathology to be cured but a multiplicity to be understood.

So much was happening in our hearts during that appointment. Was our little girl abnormal? A manifestation of a brokenness in the world? In Stark’s time, disability was thought of as a malady to be expunged from the race or locked behind walls, hidden from polite society. Now we bristle at that. Yet here I stood in the twenty-first century silently asking what the disciples asked Jesus: “Who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?”

Photograph by Jonathan Boes. Used by permission.

When the diagnosis finally came, I stammered, “But – I still like her.”

“Of course,” the psychologist in the tiny screen replied, her face reflecting my pain. “It doesn’t change the way you feel about your child.”

The grief surrounding a child’s diagnosis casts a long shadow. I was grieved, not that I was the mother of this child – my wondrous, green-eyed, orderly, funny, brilliant child – but that her future would not be as I had imagined.

Would she be in special education? I remembered from my own school days that special ed kids tended to be marked for life – a motley parade in the high school hall, the subject of disdain or at best altruism. I didn’t want her peers to see her as a pity project, and suddenly saw that I had often thought of disabled people as opportunities for my own heroism.

But now disability had bifurcated my life into before and after. What pain lay ahead for my daughter?

Peers tease Stark brutally. His mother sends him right back out to face his bullies.

“If the truth were known,” Stark writes, “my parents must have been hurting a great deal more than I was.”

I can imagine Stark’s unwieldy arms laboring toward and away from his computer keys, a man in his seventies recollecting a virile youth. “I cannot remember having a date in high school,” he writes.

In those days, it was generally felt that the handicapped should submerge their normal feeling under a layer of patient courage and go on living. I once asked advice of a woman whom I trusted. She said no decent girl would go out with me because people would stare at us. That was crushing …

When will folks realize that handicapped people are normal people with some body parts that don’t function right?

My daughter’s body functions perfectly – strong, coordinated legs and arms, a musical giggle, and precise diction when she chooses to speak (except an adorable lisp when saying her big sister’s name). Yet at communication we often reach an impasse. Her great pronunciation doesn’t change the fact that she’s clearly a gestalt language processor, mastering speech in scripts and chunks instead of word by word. We daily try to get the thoughts from her brain into the world in a way we can understand. We forge accommodations by creating blanks: “Your favorite color is …”

“Pink!”

This trick doesn’t always work. Like Stark and his community, a barrier rises between us and her.

But fences are for climbing. Stark writes about how people did not stop to hear all he had to say because his speech was so labored and slow. Yet what people expected of him – long, drawn-out, unintelligible communication – is not what he delivers in print. He writes much more simply and truly than most people do. Could this be because it took him so long to talk that he had no time to waste words?

My husband and I explored what the diagnosing psychologist had recommended: forty hours of Applied Behavioral Analysis therapy weekly. We visited the ABA center, a high-walled complex of halls and windowless rooms next to the outlet mall. Inside, therapists sat with nonverbal or frustrated children. What were they doing? Teaching them to be more like everybody else, just as purveyors of Liz Claiborne and Tommy Hilfiger next door peddled the uniforms of fashion?

Did our blondie belong here? Would she grow here? At just three years old, should she be away from us for forty hours each week?

I prayed. God, show me what to do with this child!

I felt immense pressure from all sides, having heard that adults with autism felt ABA had damaged them. Doctors, on the other hand, said it was the gold standard.

In hindsight, Stark confirmed my choice. He writes of his own institutionalization in a chapter called “Beyond Hopelessness,” in which he goes to the Newark State School for treatment of his “handicap.”

I was put in with men and boys who had such a low IQ that they hardly knew what was going on. Many of them did not know enough to go to the bathroom. Going through a door meant that an attendant unlocked and locked it behind you.

He also wrote that the disabled person benefits most from being home – in a community where people understand his capabilities and trust him.

I don’t remember what prompted me to call the local public preschool. A Southern lady with a calm voice phoned me back. Something about this teacher reassured me, and we left our daughter with her on the sidewalk that August for preschool. She cried as we pulled away.

By the end of the year with Miss Rebecca, I had read Stark’s book. And our daughter was loved by her tiny classmates. She could identify every letter of the alphabet, use the potty, and spell her own name. She called everybody, including her teacher, “Hon.” She was a person in her place.

Each of Stark’s 304 chapters is just two or three paragraphs long. I popped them like Smarties.

Stark was teaching me exactly what to expect of my daughter: As Much As Possible. He gives the counterexample of his own father. When Stark’s mother dies, his father buys a tombstone marked with all three of their names. When Stark questions why, his father says, “You’ll never get married.” Stark calls that tombstone a monument to one man’s stubbornness.

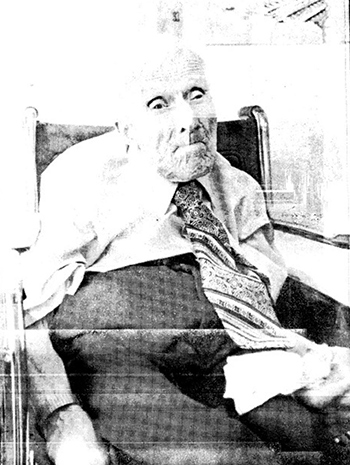

Stark Perry at 80 years. Photograph by Mary Geo Tomion for The Dundee Observer, May 3, 1995.

Stark wants to go to college, to be a civil engineer, to fight in World War II. But he can’t draw well, take notes, or go into combat. Even on the farm he proves less than ideal: “I could go after the cows, but not milk them. I could take care of chickens, but could not handle the eggs gently enough to gather them without breaking quite a few.” He loves to listen to John Philip Sousa, but he often scratches the records while putting the needle in place.

And then, partly because he stays in his community, where he is known and trusted, this man who cannot walk normally or speak normally becomes a salesman of National Press stationary, and he sells on foot.

Stark reads his future wife’s testimony in the little state paper of the Christian League for the Handicapped.

Her name was Dorothy May Munn. One side of her body was larger than the other. Her feet were too big for men’s shoes. Her handicap was, in a way, offset by a keen mind and an up and at ’em spirit.

We kept the mail hot. This woman was growing on me.

They get married on August 4, 1956.

I have not told my daughter that she is autistic. She’s busy with sidewalk chalk and Barbies, and it won’t make sense to her yet. But Stark shows me what to teach her to expect of her life when the time comes – bountiful care, great challenge, a good story.

We have children even though we know they may suffer immensely. We have them even though we know their loss or pain will make us suffer immensely.

Stark and Dorothy (Dot) start a store called Perrys’ Gifts and Groceries. They can’t carry varied stock. They also won’t sell cigarettes or open on Sundays. The business fails.

“We were so hard up in February 1958 that I did not feel that I could afford to buy my wife a valentine.” They close the store also because Dot gets pregnant, “and mommy, with her handicap, was going to need plenty of rest.”

When Dot wakes up on January 12, 1959, they call the hospital and Meeks Taxi next door.

We had a little girl but something was wrong. She never breathed right. When Dr. Stait took me home in the wee hours of the morning, he wasn’t saying much …

The next day, a few of us gathered at the family plot. Brother Albright offered prayer and we left a little white casket there.

After the loss, Stark feels Penn Yan holds little for him. He writes, “I felt a terrific desire to give out tracts in Chicago” (where Christian League for the Handicapped conventions were held each fall).

He and Dot journey west on a Greyhound bus, leaving family and friends for a strange city with almost no income. Stark hands out tracts in the Loop and at railroad stations, catching streams of humanity on their ways home from work. He preaches at small rescue missions with Dot interpreting his muddled language bit by bit. Another baby, George, is born. Stark gets hauled to jail twice for passing out tracts on the Loop. The judge threatens to have him put away because of his “mental abilities.”

Cursory online research suggests Dot’s condition was likely hemihyperplasia. I assume she wouldn’t have had access to the symptom-alleviating recourses of today: liposuction, excess skin removal, plastic surgery. In Chicago, sores start appearing on her legs and feet.

One Sunday early in 1962, I came home from passing out tracts on Maxwell Street to find a large pool of blood on the floor. The sores had started to hemorrhage.

The Perrys don’t dare go to a doctor in a city where they are unknown, fearing Dot will be hospitalized, Stark institutionalized, and George taken away. They instead ride home to New York by train, a journey Dot barely survives. Dot’s leg is amputated on arrival. She delivers another baby, Jesse, in 1963.

I can’t tell everything that took place in the decades before Stark’s finale – it’s a lot – but I’ll tell you how it all ends. Stark’s son George grows up and becomes a pastor. His son Jesse joins the military. Stark gets his first grandbaby, a girl just two years older than me. He loves her so much.

Strictly speaking, it is impossible to write the final chapter of an autobiography. Dead folks don’t type. Then, looking back over my life, with its good times and bad, I find the words ‘Thank you, LORD,’ too feeble to express my feelings. But He understands.

TO BE CONTINUED THROUGHOUT ETERNITY. January 24, 1993.

When Stark put down the pen, I was nearly two years old. To my grandmother, now eighty-four, Stark Perry was an old man. An internet search shows he died in 1997.

By the time I finished Stark’s book, I had carried it everywhere, battered it, and defiled it with marginalia. The cover had even fallen off. Closing it, I can let go of Stark’s hand and take up the hand of the little person God gave me. Stark showed me that disability is not the outstanding detail of her life. In Stark’s words about the disabled: “The best part of them is left.”

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Andrea Godwin-Stremler

Thank you for your profound article. As a disabled person, mother of a disabled daughter, and sister of 2 disabled sisters, I found your article moving, accurate, insightful, and more. Thank you. How do I find/obtain a copy of Stark Perry's book? Blessings, Andrea Godwin

Louise Brigden

What a man. A beautiful story of courage and perseverance that everyone should read.

Glen Thompson

Please PDF the book and make it available on archive.org.