Subtotal: $

Checkout-

The Island of Misfit Toys

-

A More Christian Approach to Mental Health Challenges

-

Made Perfect

-

Mary’s Song

-

The Art of Disability Parenting

-

When Merit Drives Out Grace

-

Hide and Seek with Providence

-

Unfinished Revolution

-

Falling Down

-

The Hidden Costs of Prenatal Screening

-

The Baby We Kept

-

The World Turned Right-Side Up

-

The Lion’s Mouth

-

How Funerals Differ

-

One Star above All Stars

-

Stranger in a Strange Land

-

Spaces for Every Body

-

Poem: “Consider the Shiver”

-

Poem: “No Omen but Awe”

-

Poem: “So Trued to a Roar”

-

Letters from Readers

-

Editors’ Picks: Dirty Work

-

Editors’ Picks: Millennial Nuns

-

Editors’ Picks: Directorate S

-

Letter from Brazil

-

Peace for Korea

-

Flannery O’Connor

-

Covering the Cover: Made Perfect

-

Calling from the Edge

-

The Disability Ratings Game

-

The Way Home

-

The Beginning of Understanding

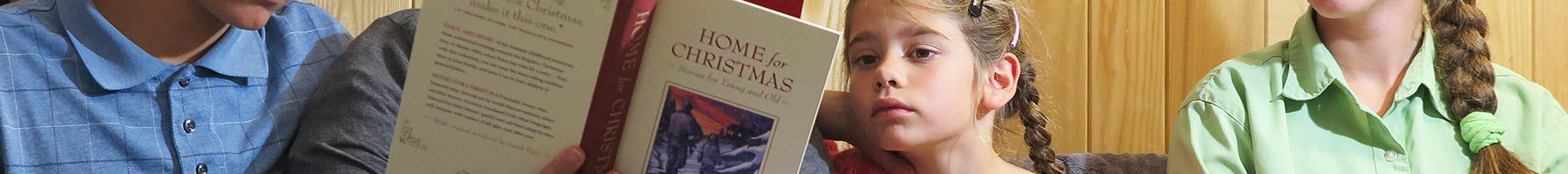

Time for a Story

Reading aloud to children takes commitment. The rewards are many.

By Maureen Swinger

December 16, 2021

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

“Uncle Wiggily Dinner!” I shouted from the foot of the stairs, then jumped out of the way as three of my brothers arrived instantaneously on the spot where I’d been standing, in a pile of blankets, arms and legs. The steep old stairs were completely worn smooth from our quilt-riding endeavors. We could stick the landing, L-bend and all, in about six seconds. Hauling our blankets along, we trooped into the living room, where my fourth brother, Duane, was already in place on his gym mat.

A 2018 study conducted by YouGov found that fewer than half of parents read aloud to their children every day. It’s not that parents aren’t aware of the proven benefits of live story time to a young child’s mind. Most non-reading households cited lack of time as the critical reason not to crack a book, followed by the distraction (their own or their children’s) caused by technological devices.

Though I love to read to my kids, I’m guilty of using both those excuses. But I should know better. I had a tech-free childhood, and a mom who had every reason to cry “No time!” but refused to do it.

Photograph courtesy of the author

When mom invented Uncle Wiggily Dinners, we were living near a university hospital so we could figure out Duane’s seizures. He was three, nonverbal and non-ambulatory. My dad worked twelve-hour days and my mom homeschooled, cleaned a ramshackle three-story house, cooked on a how-did-she-do-it budget, and managed all Duane’s care and therapy. She sewed and mended practically everything we wore. She asked neighbors if they were planning to use the apples on the forgotten trees in their yards, and canned rows of jars for the winter. I literally don’t know what she didn’t do.

She also passionately believed in books. When the call went out, we raced for the kitchen, snagged our indestructible bowls of mac ‘n cheese, then lodged ourselves and our blankets in any odd corner of the living room – the block box, the fireplace mantel, the windowsill. Someone curled up on Duane’s mat, dodging occasional flying kicks. Mom’s secondhand copy of Uncle Wiggily’s Storybook kept us all riveted as the elderly rabbit gentleman experienced hare-raising and hilarious adventures in his magical woodlands. We didn’t even grumble (too much) when it came time to wash dishes and haul ourselves and our blankets off to bed.

After we’d eaten our way through that book, the next dinner call went out for the Hundred Acre Wood. From there, it was a veritable smorgasbord. Some of the adventures got too scary to be faced from the far-flung reaches of the room. We ended up all together on Duane’s mat as the guards closed in on the pheasant-poachers in Danny the Champion of the World. Fingers locked around each other’s arms as we navigated Mio, My Son’s “Blackest Mountain beyond the Dead Forest.” Mom cruelly closed the book on Flight of the Doves’ cliffhanger chapter endings, ignoring the desperate pleas to “Read on!” which were also heard when she shared favorite childhood stories from her Swiss heritage and there was a brief pause in the action. (We did not fully appreciate her off-the-cuff translating abilities.) Sometimes the gap in translation lengthened, and we looked up to notice she’d fallen asleep. But “Read on!” the merciless cry went up.

Later years found us living at New Meadow Run Bruderhof, where the pace of life was marginally more sedate. Dad had a job with reasonable hours; we all went to school; but home life was still what one might expect with five high-energy small people, one with intense care routines. Our floors were always crosshatched with wheelchair tracks and the muddy paw prints of our slightly crazy dog. Mom hung up a sign that read, “This house is clean enough to be healthy, and dirty enough to be happy.”

After dinner, moms in the apartments down the hall were mopping. We were still sitting at our messy table, reading. The happiest evenings were during the weeks of Advent. There are some stories that demand to be heard every year: It would be a crime against the season if you didn’t join the pompous little crèche-builder, Willibald, on his trip to heaven, and hear him get an epic takedown from Saint Peter himself. Or travel with the three young schoolboys in Cárdenas, Cuba, who as the Three Kings are supposed to bring gifts to all the children of the town – or all the children whose wealthy parents have paid for the goodies. What happens when they go off script? (I’m delighted to tell you that both those classics can be found in Plough’s Home for Christmas: Stories for Young and Old).

Sometimes the stories ended with a happily-ever-after. Sometimes they ended when Duane decided to yank the tablecloth off his end with blinding speed, and a large pile of cutlery and leftovers added more patterns to the floor. The dog would make a point of not reacting to the crash, then slowly rolling off the sofa and sauntering over to pick through the wreckage for survivors.

Long winter evenings saw us in front of the big screen … or rather, behind it. The screen consisted of three bedsheets suspended from the ceiling. We borrowed construction lights (how handy to have a dad who’s an electrician) and performed shadow plays for mom and Duane. All our favorite stories were reenacted, from King Arthur to Theseus and the Minotaur to the pale green pants with nobody inside them. Sometimes it turned into an unholy mash-up with multiple converging plotlines, and we ended up howling with laughter on the floor.

This literary legacy carried over into our teen years, when we would sprawl around the living room, reading separately but together, tossing the sharp or funny lines around, someone’s feet wedged in the spokes of Duane’s wheelchair, slowly rocking him back and forth. Stacks of books teetered on every flat surface. The floor was still not what you’d call clean. We were – are – a struggling, scruffy, happy family, who love to read, act, talk, and be together. If we never thanked you till now, Mom, it’s time.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.