Subtotal: $

Checkout

Taking a Tech Sabbath

Weekend digital detoxes, even half-arsed ones like mine, are a modern iteration of one of the oldest ideas in civilization – and an act of resistance.

By Elizabeth Oldfield

July 2, 2024

On Friday night, roughly as my work day ends, I turn off my phone, my iPad and my laptop and light a candle. It’s a precious moment of peace. Then I jump up, hunt down a housemate, thrust all my devices hurriedly into her arms and ask her to hide them and (this with slightly wild eyes) NOT give them back to me on pain of death for twenty-four hours.

Sometimes it works. Often it doesn’t, because the way we have set up society means there is usually (what seems like) a very important reason to turn them back on. If I can’t get said housemate to crack I just use my husband’s phone. More recently, we’ve tried committing to doing this together, as a community, which has helped a bit. I still successfully manage twenty-four hours off devices only about half the time, but the attempt every week feels important.

Tech sabbaths and digital detoxes, even half-arsed ones like mine, are a modern iteration of one of the oldest ideas in civilization. In the second chapter of the Hebrew Bible, itself one of the oldest documents we have, God undertakes six days of creative work, and rests on the seventh. He blesses the day and declares it “holy.”

Theologian Walter Brueggemann called the practice of sabbath an act of resistance. The word conjures French fighters, stylishly sabotaging Nazi infrastructure while smoking Gauloises. Imagining myself in a beret with red lipstick really helps when I attempt to turn off my phone for a day. It’s certainly a more attractive image than the grey, dull associations most of us carry. Sabbath sounds to us like the shop closing early just when we’ve run out of milk. It sounds like restriction. Which it is. But it is also (and this will be a theme) through restriction, liberation.

For most of the week, my value is in what I produce and what I consume. If I’m not careful my main goal in a day becomes being impressive and competent, subtly signaling my status with the things I buy, say, and post.

Sabbath is the opposite. It is a line in the sand. Today I am just a person, and a person is beyond price. Sabbath is about valuing, fighting for, and fiercely guarding rest.

I have never been a workaholic, never found boundaries around work a problem, which feels more shameful than admitting to a niche sexual proclivity in public. Work addiction is almost encouraged.

I have had to learn to choose rest in a culture that only really recognizes frantic work and exhausted, passive leisure, ideally consumed using the same screens we’ve been working on all day, produced by the same small number of global corporations. Despite being deeply convinced of my need for rest, sometimes the only way I can justify sabbath to myself is on a productivity basis. Jews, who have been persecuted and mocked partly for their observance of it, have had to do this over the centuries. The Romans (proto-neoliberals?) were contemptuous of it, believing it revealed laziness to have a day off a week. Philo, a first-century Jew, made the case that his community was more effective and productive because of their day off: “A breathing spell enables not merely ordinary people but athletes also to collect their strength with a stronger force behind them to undertake promptly and patiently each of the tasks set before them.” Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, though, condemns this justification, saying, “Here the Sabbath is represented not in the spirit of the Bible but in the spirit of Aristotle.” For Jews and Christians, the sabbath is not designed to serve work, because love, not work, is our ultimate end. It always moves me that the sabbath command was given directly after the Exodus, to a nation that had until recently been enslaved for generations. There is a tenderness in mandating rest and play for traumatized people who had only ever known enforced labor.

Mandated time to rest seems a foreign notion now. It’s become one of the few clear political intuitions I have: that it shouldn’t be. Breaking time, and people, into ever flexible units of production is one of the strongest drivers of disconnection that we experience. I have come to see sabbath as central for my personal project of connection, with myself, with my family and community, and with God. It’s a relational reset every week, a bulwark against the instrumentalization of relationships and the commodification of time.

Sabbath is, it is important to underline, a deeply Jewish practice. It is no accident that I have mainly quoted rabbis in this section. Christians share a commitment to it in theory, and several denominations observe it strictly, but many others have been far less disciplined in practice, at least in the last century. It is not quite appropriation for Christians and others to adopt it, but I think it’s only polite to acknowledge that sabbath is a gift from the Jews to the world.

Honestly, before I started being intentional about it, I thought I was pretty good at rest. Acedia is a temptation for me, and so is straight sloth itself, the desire to down tools and get in the bath with a book always lurking at the back of my mind. I have never been a workaholic, never found boundaries around work a problem, which feels more shameful than admitting to a niche sexual proclivity in public. Work addiction is almost encouraged. In writing that I don’t suffer from this temptation, I fear judgment. What if someone reads this and decides not to hire me when I need a job? This push to be always performing productively for imaginary future employers or clients is a large part of what makes rest so hard. It feels embarrassing.

Every time I prayed, this phrase floated up in my mind: Stop and rest. Like an annoying fly, it just would not go away. It made me tut and mentally swat. Ha! Rest.

As a leader of a think tank I tried to resist this culture: to make sure we had reasonable hours, people took their holidays, and we’d all go to the pub at four on a Thursday. I believed – and still believe – that it is possible for people and organizations to be effective and creative and strive for excellence in a sustainable way, without burning out, without the extractive pace that so quickly curdles work relationships. Then the pandemic hit, and trying to hold an organization together over Zoom while homeschooling threw all my careful balance completely out of whack. The financial fear and the worry for my team, many of them isolated and clinically vulnerable, meant I worked harder and harder. I was determined that the organization would not only survive but do it healthily and relationally. And we did, mainly. But I was not healthy. I had a persistent twitch in my left eye and back pain so bad I had to do most of my meetings lying down. Like most of us, I just kept going.

By January 2021, every time I prayed, this phrase floated up in my mind: Stop and rest. Like an annoying fly, it just would not go away. It made me tut and mentally swat. Ha! Rest. Chance would be a fine thing. But it stayed, quiet and compassionate, sweet-smelling somehow, and I began to wonder whether, rather than just my wishful subconscious, it might be some kind of guidance from God. For context, I don’t hear God’s voice at all clearly or regularly. I don’t even know quite what I mean by that phrase. Characters in the Bible have angels appear to them, or vivid dreams, but when it happens for me it is much subtler and slower than that. A dawning sense in prayer that I need to do something, or in this case stop something, and a tug on my conscience when I try to ignore it. It had only happened this clearly twice before.

You are very welcome to explain it away. You might call it my intuition, or listening to my body. I don’t think the explanations are mutually exclusive. Either way, by February I had conceded that this was something I needed to listen to, that it was time to leave my job, but I was full of fear. I was then the main wage earner in my family and we didn’t know how to make the math work. What savings we had were in the hope of being able to buy a community home, and we were renting with another family at this point, and already spending more than our income. Stepping away from a job I loved without a plan or a safety net felt scary financially and also a threat to my identity. Who was I, without something to say when people asked, “So what do you do?” I had been a promising young woman. I didn’t know if I wanted to be just a woman.

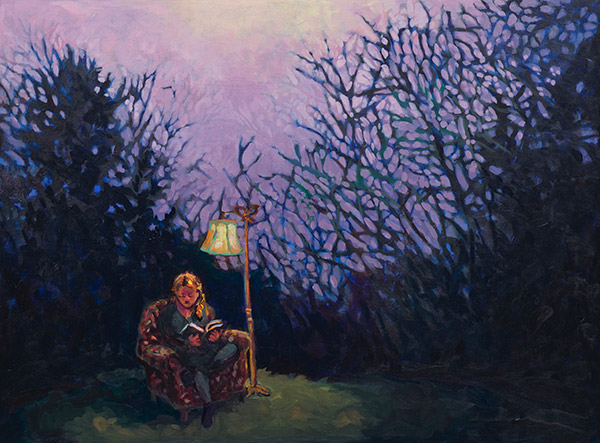

Carol Aust, Reading in a Night Wood, 2016, acrylic on panel. Used by permission.

I needed to stop and rest and trust that life is not a treadmill, that it is not, in fact, me who holds up the sky. We decided we would take the leap and hope that our past experience of following these leadings would be repeated.

So I handed in my notice and wrote a leaving blog that said, essentially, “I don’t have an impressive next job to announce or a flashy future project to share. I’m just stopping for a rest and I don’t know what’s next.” That short, off-the-cuff final piece has had more response than anything else I have ever written. I posted it on LinkedIn, headquarters of performing productivity, and had my inbox flooded with messages of support and relief. People shared it to their feeds and strangers messaged me saying that they didn’t know you were allowed to say things like that in public without it being code for a politician having an affair. Three people told me I had inspired them to quit their jobs too, which seemed a lot of responsibility. It was a tiny version of the response Jacinda Ardern, Prime Minister of New Zealand, got a few years later when she stepped down, saying honestly that she was just too exhausted to do a good job. Everyone who heard it felt their shoulders relax a tiny bit. We all felt, suddenly, that it is OK to admit you’re human, even when you’re running the world.

And rest is, fundamentally, about being human. About recognizing our limits when advertising tells us we are limitless. It requires intention, and working out what we do actually find restorative. It is going in the bath with a book for me (but not with an iPad), or gardening, or rollerblading, or puttering around charity shops without my phone. I need to not have access to the news or social media in order to rest.

It might seem counterintuitive to prescribe rest as a medicine for the sin that is often known as sloth, but I think it’s right. Proper rhythms of real rest rather than passive leisure consumption make focus easier when we need to work, and make it more likely we will find joy and flow in it when we do.

From Elizabeth Oldfield, Fully Alive: Tending to the Soul in Turbulent Times (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2024), 109–115.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Dennis Dieball

How very sad that we have reached a point in society where acknowledging the human need for rest is an embarrassment. "No limits" may be good advertising, but it is very bad policy.